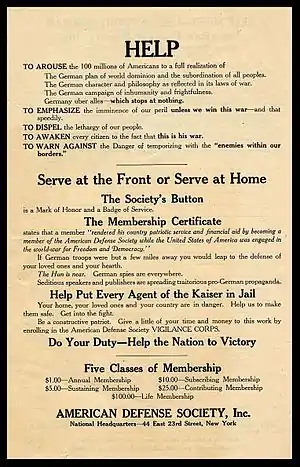

The American Defense Society (ADS) was a nationalist American political group founded in 1915. The ADS was formed to advocate for American intervention in World War I against the German Empire. The group later stood in opposition to the Bolsheviks, who came to power in Russia after the October Revolution of 1917, and the proposed American participation in the League of Nations.

In domestic politics, the ADS launched a campaign to eliminate instruction of the German language in the United States.[1] As a nationalist outfit, the ADS demanded "100 percent Americanism" amid fears over the loyalties of "hyphenated Americans".[2]

The organization's first honorary president was former President Theodore Roosevelt.[3] After declining post-World War I, the ADS made a brief resurgence prior to World War II, where the group fought President Franklin Delano Roosevelt's effort to expand the Supreme Court.[4]

Formation

Clarence Smedley Thomas, Cushing Stetson, and John F. Hubbard formed the ADS in August 1915 as a splinter group from the National Security League (NSL). They objected to the NSL for being uncritical in support of the Wilson administration. Like the NSL, the ADS favored progressivism and its reform programs, but the ADS was much more militarist and nationalistic than the NSL.

Leadership

The ADS's first honorary president was former U.S. President Theodore Roosevelt.[3] The chairman of the ADS was Richard Melancthon Hurd, a close friend of Roosevelt and a career real estate economist.

Goals

Among the political positions of the ADS were:

- Total victory against Germany in World War I, with no discussion of peace terms

- Centralized organization of national industry, as accomplished temporarily under the War Industries Board

- Expulsion of socialists from US politics

- Suppression of sedition

- One hundred percent Americanism

In February 1918, the Society called on Congress to take action on a series of measures required by US entry into World War I. It wanted an "overwhelming force" sent to France: "the quicker we put our full strength into the war the sooner it will be over."[5] It called for the internment of enemy aliens and sympathizers to prevent sabotage because "if enough munition factories are blown up here we shall lose the war."[5][6] It claimed that England saw an end to foreign plots and propaganda after interning 70,000. On the educational and cultural front, the Society was uncompromising:

"The appalling and complete breakdown of German Kultur compels a sweeping revision of the attitude of civilized nations and individuals toward the German language, literature, and science. The close scrutiny of German thought induced by 'Hun' frightfulness in this war has revealed abhorrent qualities hitherto unknown, and to most people unsuspected. Hereafter, throughout every English-speaking country on the globe, the German language will be a dead language. Out with it forever!"[5]

The ADS also called for compulsory military training for all men between the ages of 18 and 21[5] In late 1918, it launched a campaign to eliminate instruction in German nationwide.[1]

Interwar period

After World War I, the ADS joined the campaign against American participation in the League of Nations. It described the League as a surrender of national sovereignty "obnoxious to the Constitution of the United States." It denounced "the impossible doctrines of the self-determination of races which is contrary to our fundamental doctrines as a nation."[7]

The ADS was officially nonpartisan, but in 1920, Charles Stewart Davison, Chairman of the Board of Trustees, wrote an open letter to its officers, members, and contributors to urging them to support the Republican presidential ticket of Warren Harding and Calvin Coolidge.[8]

The manager of the ADS's Washington Bureau in the 1920s was Richard Merrill Whitney, the author of an exposé of radical activity, The Reds in America.[9]

The ADS made a brief resurgence during the years immediately before World War II. The group conducted a campaign against the attempt of President Franklin Roosevelt to "pack" the US Supreme Court by expanding its number of members.[4]

Final years

Later, the group was hamstrung by the death of two of its principals: Board Chairman Davison in 1942 and Board Chairman Elon Huntington Hooker in 1948.[4]

In its final years, it maintained its public profile by giving awards. In 1939, it presented awards called the Atlantic Fleet Silver Cup for excellence in gunnery and the Distinguished Service Gold Medal for work on behalf of national defense and preparedness.[10] In 1943, it honored Theodore Roosevelt on the 85th anniversary of his birth.[3]

The ADS seems to have disappeared from New York City directories in 1956.[4]

References

- 1 2 New York Times: "To Fight German Teaching," December 31, 1918, accessed January 7, 2010

- ↑ Wüstenbecker, Katja. "German-Americans during World War I". Immigrant Entrepreneurship. Retrieved 2022-05-01.

- 1 2 3 New York Times: "Theodore Roosevelt to be Honored Today," October 27, 1943, accessed March 30, 2010

- 1 2 3 4 Melissa Haley, "Guide to the Records of the American Defense Society, 1915-1942. New-York Historical Society.

- 1 2 3 4 New York Times: "Calls for Strict Ban on German Language," February 25, 1918, accessed January 7, 2010

- ↑ The reference was probably to the sabotage of a New York harbor munitions depot in 1916.

- ↑ New York Times: "Files 10 Objections to Nations' League," September 1, 1919, accessed March 30, 2010. Signing the organization's letter sent to each US senator were Charles Stewart Davison, John R. Rathom, George B. Agnew, Richard Washburn Child, Dr. William T. Hornaday, Newton W. Gilbert, Lee de Forest, William Guggenheim, Robert Appleton, Dr. L.L. Seaman, C[larence].S[medley]. Thompson, Raymond L. Tiffany, J.P. Harris, and Charles Larned Robinson.

- ↑ New York Times: "Makes Plea for Harding," August 28, 1920, accessed March 30, 2010

- ↑ New York Times: "R.M. Whitney Dies Suddenly in Hotel," August 17, 1924, accessed March 30, 2010. Whitney was a Harvard graduate and a witness for the prosecution at the trial of William Z. Foster.

- ↑ New York Times: "To Get Defense Awards," November 26, 1939, accessed March 30, 2010

Sources

- Hand Book of the American Defense Society, New York: National Headquarters, February 1918.

- Franz, Manuel. "Preparedness Revisited: Civilian Societies and the Campaign for American Defense, 1914-1920," in Journal of the Gilded Age and Progressive Era 17:4 (2018): 663–676.

- John Higham, Strangers in the Land. New York: Atheneum, 1981.

- William Temple Hornaday, A Searchlight on Germany: Germany's Blunders, Crime and Punishment. New York: American Defense Society, 1917.

- William Temple Hornaday, The Lying Lure of Bolshevism. New York: American Defense Society, 1919.