| Amlaíb Conung | |

|---|---|

| "King of the Foreigners" | |

| Reign | c. 853–871 |

| Died | c. 874 |

| Issue | Oistin Carlus |

| Father | Gofraid |

Amlaíb Conung (Old Norse: Óláfr [ˈoːˌlɑːvz̠]; died c. 874) was a Viking[nb 1] leader in Ireland and Scotland in the mid-late ninth century. He was the son of the king of Lochlann, identified in the non-contemporary Fragmentary Annals of Ireland as Gofraid, and brother of Auisle and Ímar, the latter of whom founded the Uí Ímair dynasty, and whose descendants would go on to dominate the Irish Sea region for several centuries. Another Viking leader, Halfdan Ragnarsson, is considered by some scholars to be another brother. The Irish Annals title Amlaíb, Ímar and Auisle "kings of the foreigners". Modern scholars use the title "kings of Dublin" after the Viking settlement which formed the base of their power. The epithet "Conung" is derived from the Old Norse konungr and simply means "king".[2] Some scholars consider Amlaíb to be identical to Olaf the White, a Viking sea-king who features in the Landnámabók and other Icelandic sagas.

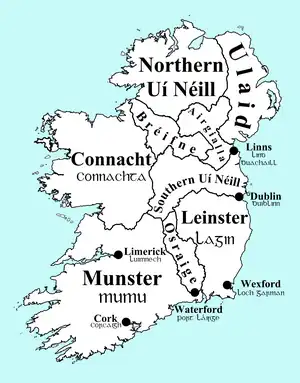

During the late 850s and early 860s Amlaíb was involved in a protracted conflict with Máel Sechnaill, overking of the Southern Uí Néill and the most powerful ruler in Ireland. The cause of the conflict is uncertain, but it may have been sparked by competition for control of Munster and its resources. Amlaíb allied successively with Cerball, King of Ossory and Áed Findliath, overking of the Northern Uí Néill against Máel Sechnaill. Máel Sechnaill died in 862 and his lands were split, effectively ending the conflict. Following this Amlaíb and his kin warred with several Irish leaders in an attempt to expand their kingdom's influence. In later years Amlaíb conducted extensive raids in Scotland, though these were interrupted by a war in 868 against his former ally Áed Findliath when several Viking longphorts along the northern coast were razed. Amlaíb disappears from contemporary annals in 871. Later accounts say he returned to Lochlann to aid his father in a war, and the Pictish Chronicle says he died in battle against Constantine I of Scotland. This event is usually dated to 874.

Background

The earliest recorded Viking raids in Ireland occurred in 795.[3] Over time, these raids increased in intensity, and they overwintered in Ireland for the first time in 840–841.[4] Later in 841 a longphort was constructed at Áth Cliath (Irish for hurdled ford), a site which would later develop into the city of Dublin.[5] Longphorts were also established at other sites around Ireland, some of which developed into larger Viking settlements over time. The Viking population in Ireland was boosted in 851 with the arrival of a large group known as "dark foreigners" – a contentious term usually considered to mean the newly arrived Vikings, as opposed to the "fair foreigners", i.e., the Viking population which was resident in arrival prior to this influx.[nb 2][7] A kingdom in Viking Scotland was established by the mid ninth-century, and it exerted control over some of the Vikings in Ireland. By 853 a separate kingdom of Dublin had been set up which claimed control over all the Vikings in Ireland.[8]

Biography

Arrival in Ireland

The earliest mention of Amlaíb Conung is in the Annals of Ulster, which in 853 describe his arrival in Ireland:

Amlaíb, son of the king of Lochlann, came to Ireland, and the foreigners of Ireland submitted to him, and he took tribute from the Irish.[9]

Amlaíb is named in the annals as a "king of the foreigners", but in modern texts he is usually labelled the first king of Dublin, after the Viking settlement which was the base of his power.[10] His brothers arrived in Ireland later and ruled together as co-kings.[11] The Fragmentary Annals go into more detail regarding Amlaíb's arrival[nb 3]:

Also in this year, i.e., the sixth year of the reign of Máel Sechlainn, Amlaíb Conung, son of the king of Lochlann, came to Ireland, and he brought with him a proclamation of many tributes and taxes from his father, and he departed suddenly. Then his younger brother Ímar came after him to levy the same tribute.[nb 4][14]

Lochlann, originally Laithlinn or Lothlend, the land where Amlaíb's father was king, is often identified with Norway, but it is not universally accepted that it had such a meaning in early times.[15] Several historians have proposed instead that in early times, and certainly as late as the Battle of Clontarf in 1014, Laithlinn refers to the Norse and Norse-Gael lands in the Hebrides, the Isle of Man, the Northern Isles and parts of mainland Scotland.[16] Whatever the original sense, by the twelfth century, when Magnus Barefoot undertook his expedition to the West, it had come to mean Norway.[17]

War with Máel Sechnaill

If he did indeed leave Ireland, Amlaíb had returned by 857 at the latest when he and Ímar fought against Máel Sechnaill,[nb 5] overking of the Southern Uí Néill, and a group of Vikings sometimes known as the Norse-Irish.[nb 6] Máel Sechnaill was the most powerful king in Ireland at the time and his lands lay close to the Viking settlement of Dublin.[20] The fighting began in the previous year: "Great warfare between the heathens and Mael Sechnaill, supported by Norse-Irish" is reported by the Annals of Ulster.[21]

The fighting was focused on Munster; Máel Sechnaill sought to increase his influence over the kings there.[20] He took hostages from the province in 854, 856 and 858,[22] and the power of the over-kings had been weakened in 856 by a Viking raid on the royal centre at Lough Cend, when Gormán son of Lonán, a relative of Munster's over-king, was killed alongside a great many others.[23] This weakness likely drew the gaze of both Máel Sechnaill and the Vikings, and their competition for Munster's resources may have been the cause of the war.[20] Early battles seem to have gone the way of the Vikings: Amlaíb and Ímar "inflicted a rout on Caitill the Fair and his Norse-Irish in the lands of Munster".[24] Although there is no certain evidence to suggest that this Caitill is the same person as the Ketill Flatnose of later sagas, Anderson and Crawford have suggested that they are the same person.[25]

In 858 Ímar, allied with Cerball, King of Ossory, routed a force of Norse-Irish at Araid Tíre (east of Lough Derg and the Shannon in modern-day County Tipperary).[26] Ossory was a small kingdom wedged between the larger realms of Munster and Leinster. At the beginning of his reign in the 840s, Cerball's allegiance was pledged to the over-king of Munster, but as that kingdom grew weaker Ossory's strategic location allowed opportunities for his advancement.[27] Cerball had previously fought against the Vikings, but he allied with them to challenge the supremacy of Máel Sechnaill and his Norse-Irish allies.[28] The following year Amlaíb, Ímar and Cerball conducted a raid on Máel Sechnaill's heartlands in Meath,[nb 7] and in consequence a royal conference was held at Rathugh (modern-day County Westmeath).[30] Following this meeting Cerball shed his allegiance to the Vikings and formally submitted to Máel Sechnaill in order to "make peace and amity between the men of Ireland".[31]

With their ally turned against them, Amlaíb and Ímar sought a new alliance with Áed Findliath, overking of the Northern Uí Néill, and rival of Máel Sechnaill.[32] In 860 Máel Sechnaill and Cerball led a large army of men from Munster, Leinster, Connacht and the Southern Uí Néill into the lands of Áed Findliath near Armagh. While the southern forces were encamped there, Áed launched a night attack, killing some of the southern men, but his forces took many casualties and were forced to retreat.[nb 8][33] In retaliation for this invasion Amlaíb and Áed led raids into Meath in 861 and 862, but they were driven off both times.[34] According to the Fragmentary Annals this alliance had been cemented by a political marriage:

Áed son of Niall and his son-in-law Amlaíb (Áed's daughter was Amlaíb's wife) went with great armies of Irish and Norwegians to the plain of Mide, and they plundered it and killed many freemen.[nb 9][35]

In later years, alliance between the Northern Uí Néill and the Vikings of Dublin became a regular occurrence: the Northern and Southern Uí Néill were frequent competitors for supremacy in Ireland, and the uneasy neighbourhood between Dublin and the Southern Uí Néill made the Vikings natural allies for the Northerners.[32]

Later campaigns

Máel Sechnaill died in 862, and his territory in Meath was split between two rulers, Lorcán mac Cathail and Conchobar mac Donnchada.[36] Amlaíb and Ímar, now joined in Ireland by their younger brother Auisle, sought to make use of this change to extend their influence in the lands of the Southern Uí Néill.[37] In 863 the three brothers raided Brega in alliance with Lorcán, and the following year Amlaíb drowned Conchobar at Clonard Abbey.[38] Muirecán mac Diarmata, overking of the Uí Dúnchada, was killed by Vikings in 863, probably by Amlaíb and his kin trying to expand into Leinster.[nb 10][40]

Beginning around 864 the three brothers halted their campaigns of conquest in Ireland, and instead campaigned in Britain.[41] Ímar disappears from the Irish Annals in 864, and does not reappear until 870. Downham concludes he is identical to Ivar the Boneless, a Viking leader who was active in England during this period as a commander of the Great Heathen Army.[42] According to O Croinin "Ímar has been identified with Ívarr Beinlausi (the boneless), son of Ragnar Lodbrok, but the matter is controversial".[43] In 866 Amlaíb and Auisle led a large army to Pictland and raided much of the country, taking away many hostages.[44]

The native Irish kings took advantage of this absence to fight back against the growing Viking power in Ireland. In 866 a number of longphorts along the northern coast were destroyed by Áed Findliath, overking of the Northern Uí Néill.[45] It is possible that Áed was still allied with Amlaíb at this point, and that the longphorts which were razed belonged to Vikings not affiliated with the Dubliners, but by 868 at the latest Amlaíb and Áed were at war.[46] In 865 or 866 a battle was won by Flann mac Conaing, overking of Brega, against the Vikings, possibly in retaliation for the raids on his land by Amlaíb and his brothers in 863.[47] Numerous further setbacks for the Vikings occurred in 866–867 when their camps at Cork and Youghal were destroyed, an army was routed in Kerry, two battles were lost against the native Irish in Leinster, and Amlaíb's fort at Clondalkin was destroyed.[48]

Amlaíb returned to Ireland in 867, probably to try to stop this string of defeats.[49] His return is attested to in the Annals of Inisfallen, which mention an "act of treachery" committed against the church of Lismore (modern-day County Waterford).[50] Around this time his brother Auisle was murdered by a kinsman, possibly by Amlaíb himself.[51] In 868 another of Amlaíb's kinsmen was killed, this time his son Carlus, who died in battle at Killineer (near the Boyne, County Louth), fighting against the forces of Amlaíb's former ally Áed Findliath. This battle was a significant victory for the Northern Uí Néill and is recorded in many Irish chronicles.[52] In retaliation for this defeat Amlaíb raided the monastery at Armagh, which was one of the most important religious sites patronised by the over-kings of the Northern Uí Néill.[53]

In 870 the situation of the Vikings was improved by infighting amongst the ruling Irish of Leinster. Another victory came that year when a previously unknown "dark foreigner" known as Úlfr killed a king of southern Brega.[54] The situation had evidently stabilised enough for Amlaíb to go raiding in Britain again: in 870 Amlaíb and Ímar (once more appearing in the Irish Annals after an absence of six years) laid siege to Dumbarton Rock, the chief fortress of the Kingdom of Strathclyde, and captured it following a four-month siege.[55] The pair returned to Dublin in 871 with 200 ships and they "brought with them in captivity a great prey of Angles, Britons and Picts".[56]

Amlaíb's return to Dublin in 871 is the final time he is mentioned in contemporary annals, but according to the Fragmentary Annals he returned to Lochlann that year to aid his father Gofraid in a war.[57] According to the Pictish Chronicle, he died around 874 during a protracted campaign against Constantine I in Scotland:[nb 11][60]

...after two years Amlaib, with his people, laid waste Pictavia; and he dwelt there from 1 January until the feast of Saint Patrick. Again in the third year Amlaib, while collecting tribute, was killed by Constantine. A short while after that battle was fought in his 14th year at Dollar between the Danes and the Scots, the Scots were annihilated at Atholl. The Norsemen spent a whole year in Pictavia.[61]

Identification with Olaf the White

The Viking sea-king Olaf the White, who features in several Nordic sagas, is positively identified with Amlaíb by Hudson.[62] According to Holman, "Olaf is usually identified with the Amlaíb that is the first recorded king of the Vikings in Ireland."[63] The Landnámabók says that Olaf the White landed in Ireland in 852 and established the kingdom of Dublin, closely corresponding to the Irish annals' account of Amlaíb.[64] Amlaíb's lineage according to this saga is as follows:

...he was the son of Ingald, the son of Helgi, the son of Olaf, the son of Gudraud, the son of Halfdan Whiteleg, the King of the Uplanders.[65]

The Laxdæla saga offers a slightly different genealogy, naming Olaf the son of Ingjald, the son of King Frodi the Valiant.[63] Both of these options are problematic since according to the Irish annals (albeit the non-contemporary Fragmentary Annals) Amlaíb was the son of Gofraid, King of Lochlann.[66] The sagas identify Aud the Deep-minded, daughter of Ketill Flatnose, as Olaf's wife, but the Irish annals name a daughter of Áed Findliath as the spouse of Amlaíb in one account, and the daughter of "Cináed" in another.[67] They also disagree on Amlaíb/Olaf's children, the sagas naming Thorstein the Red, and the annals naming Oistin and Carlus.[68] Todd in his translation of Cogadh Gaedhel re Gallaibh suggests that Thorstein and Oistin are the same person, but later historians have rejected this due to "the obvious discrepancy of their dates".[69]

A further complication is that the Pictish Chronicle says Amlaíb was killed in battle in Scotland, whereas the sagas say Olaf was killed in battle in Ireland.[70] Hudson proposes a solution for this apparent contradiction—the Vikings did not distinguish between the Gaelic peoples of Scotland and Ireland.[62]

Family

Amlaíb's father is identified as Gofraid by the Fragmentary Annals.[66] He was joined in Ireland by his brother Ímar sometime in or before 857[24] and by his brother Auisle sometime in or before 863.[71] The three are identified as "kings of the foreigners" by the Annals of Ulster in 863,[71] and as brothers by the Fragmentary Annals:

The king had three sons: Amlaíb, Ímar, and Óisle.[nb 12] Óisle was the least of them in age, but he was the greatest in valor, for he outshone the Irish in casting javelins and in strength with spears. He outshone the Norwegians in strength with swords and in shooting arrows. His brothers loathed him greatly, and Amlaíb the most; the causes of the hatred are not told because of their length.[72]

The Annals of Ulster say that Auisle was killed in 867 by "kinsmen in parricide".[73] The Fragmentary Annals state explicitly that Amlaíb and Ímar were responsible for their brother's death:

[Auisle] said: 'Brother,' he said, 'if your wife, i.e., the daughter of Cináed, does not love you, why not give her to me, and whatever you have lost by her, I shall give to you.' When Amlaíb heard that, he was seized with great jealousy, and he drew his sword, and struck it into the head of Óisle, his brother, so that he killed him.[72]

Some scholars identify Halfdan Ragnarsson as another brother.[74] This identification is contingent upon Ímar being identical to Ivar the Boneless: Halfdan and Ivar are named as brothers in the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle.[75][nb 13][nb 14] According to the Annals of Ulster Amlaíb's son Oistin was slain in battle by "Albann" in 875.[77] This figure is generally agreed to be Halfdan.[78] If that is correct, then it may explain the reason for the conflict: it was a dynastic squabble for control of the kingdom.[79] One potential problem is that according to Norse tradition Ivar and Halfdan were the sons of Ragnar Lodbrok, whereas Ímar and Amlaíb are named as sons of Gofraid in the Fragmentary Annals.[80] However, the historicity of Ragnar is uncertain and the identification of Ragnar as the father of Ivar and Halfdan is not to be relied upon.[81]

Two wives of Amlaíb are mentioned by the annals. The first, an unnamed daughter of Áed Findliath is mentioned in passing by the Fragmentary Annals with regards to an alliance between Amlaíb and Áed.[35] Elsewhere the Fragmentary Annals, when reporting the death of Auisle, refer to "the daughter of Cináed" as Amlaíb's wife.[72] It has been suggested that the reference to Áed is mistaken, and that Amlaíb's wife was a daughter of Cináed mac Conaing, who had been drowned by Máel Sechnaill in 851.[82] Another possibility is that the Cináed in question is Cináed mac Ailpín (i.e., Kenneth MacAlpin, which would make Amlaíb a brother-in-law of his killer Constantine I, a son of Kenneth).[83] Two sons are noted by the annals: Oistin and Carlus, each of whom is mentioned a single time.[84] Both died violently: Carlus died in 868 fighting against Áed Findliath and Oistin was "deceitfully killed by Albann" in 875.[85]

Family tree

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Notes:

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Notes

- ↑ The definition as given by Downham is used here: Vikings were "people of Scandinavian culture who were active outside of Scandinavia".[1]

- ↑ Dubgaill and Finngaill respectively in Old Irish. Amlaíb and his kin are counted among the Dubgaill.[6]

- ↑ The Fragmentary Annals were written several hundred years after the events they describe, and are considered less reliable than earlier annals such as the Annals of Ulster which may have served, along with historically dubious sagas, as partial sources for the Fragmentary Annals.[12]

- ↑ Ó Corrain dates this to 852–853.[13]

- ↑ Some sources use the name "Máel Sechnaill" and some use "Máel Sechlainn" to refer to this person.[18]

- ↑ "Norse-Irish" is a translation of the Old Irish term Gallgoídil (literally Foreigner-Gaels). The origins of this group are debated, but they are usually considered Vikings of mixed Gaelic and Scandinavian culture. They do not appear in the Irish Annals after 858, possibly because in later years mixed-ethnicity was the norm, rather than the exception.[19]

- ↑ "Meath" refers to a territory corresponding to modern Counties Meath and Westmeath, plus neighbouring areas, not modern County Meath alone. This territory was controlled by the Southern Uí Néill.[29]

- ↑ Here, "southern" is used to refer to Máel Sechnaill and his allies.

- ↑ "Mide" is the Old Irish term for Meath.

- ↑ Thirty years previously Muirecán and his kin had claimed to be overkings of Leinster, but by the time of his death the success of Máel Sechnaill in imposing his authority in Leinster, combined with debilitating Viking raids had reduced the territory ruled by Muirecán's dynasty to "Naas and the eastern plain of the River Liffey".[39]

- ↑ An alternative date of 872 for Amlaíb's death has been proposed, perhaps explaining why Ímar is named as "king of the Norsemen of all Ireland and Britain"[58] upon his death in 873.[59]

- ↑ The name Óisle is a variant of Auisle.

- ↑ The identification of Ímar and Ivar as being one and the same is generally agreed upon.[76]

- ↑ Another unnamed brother is mentioned in the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle: "...the brother of Ingwar [Ivar] and Healfden [Halfdan] landed in Wessex, in Devonshire, with three and twenty ships, and there was he slain, and eight hundred men with him, and forty of his army. There also was taken the war-flag, which they called the raven."[75]

References

Citations

- ↑ Downham, p. xvi

- ↑ Ó Corrain, p. 2

- ↑ Ó Corrain, p. 27; Annals of Ulster, s.a. 795

- ↑ Ó Corrain, p. 28; Annals of Ulster, s.a. 840

- ↑ Holman, p. 180

- ↑ Downham, p. xvii; Ó Corrain, p. 7

- ↑ Downham, p. 14

- ↑ Ó Corrain, p. 28–29

- ↑ Annals of Ulster, s.a. 853

- ↑ Holman, p. 107; Clarke et al., p. 62; Ó Corrain, p. 28–29

- ↑ Woolf, p. 108

- ↑ Radner, p. 322–325

- ↑ Ó Corrain, p. 7

- ↑ Fragmentary Annals of Ireland, § 239; Anderson, pp. 281–284

- ↑ Ó Corrain, p. 9

- ↑ Ó Corrain, pp. 14–21; Helle, p. 204

- ↑ Ó Corrain, pp. 22–24

- ↑ Ó Corrain, pp. 6, 30; Downham, p. 17

- ↑ Downham, p. 18

- 1 2 3 Downham, p. 17

- ↑ Annals of Ulster, s.a. 856; Ó Corrain, p. 30

- ↑ Annals of the Four Masters, s.aa. 854, 856, 858; Annals of Ulster, s.aa. 854, 856, 858; Choronicon Scotorum, s.aa. 854, 856, 858

- ↑ Downham, p. 17; Annals of Ulster, s.a. 856; Choronicon Scotorum, s.a. 856

- 1 2 Annals of Ulster, s.a. 857

- ↑ Anderson, p. 286, note 1; Crawford, p. 47

- ↑ Ó Corrain, p. 30; Downham, p. 18; Annals of the Four Masters, s.a. 858; Choronicon Scotorum, s.a. 858

- ↑ Duffy, p. 122

- ↑ Duffy, p. 122; Annals of Ulster, s.a. 847

- ↑ Downham, p. 19, note 47

- ↑ Downham, p. 19; Duffy, p. 122; Annals of Ulster, s.a. 859; Annals of the Four Masters, s.a. 859; Choronicon Scotorum, s.a. 859

- ↑ Annals of Ulster, s.a. 859

- 1 2 Downham, p. 19

- ↑ Downham, p. 19; Annals of the Four Masters, s.a. 860; Annals of Ulster, s.a. 860; Choronicon Scotorum, s.a. 860; Fragmentary Annals of Ireland, § 279

- ↑ Downham, p. 19; Annals of the Four Masters, s.aa. 861, 862; Annals of Ulster, s.aa. 861, 862; Choronicon Scotorum, s.a. 861

- 1 2 Fragmentary Annals of Ireland, § 292

- ↑ Downham, p. 20; Annals of Clonmacnoise, s.a. 862; Annals of the Four Masters, s.a. 862; Annals of Ulster, s.a. 862; Choronicon Scotorum, s.a. 862

- ↑ Downham, p. 20

- ↑ Downham, p. 20; Annals of Clonmacnoise, s.a. 864; Annals of Ulster, s.a. 864; Choronicon Scotorum, s.a. 864

- ↑ Downham, pp. 20–21

- ↑ Downham, p. 20; Annals of the Four Masters, s.a. 863; Annals of Ulster, s.a. 863; Choronicon Scotorum, s.a. 863

- ↑ Downham, p. 21

- ↑ Downham, pp. 64–67, 139–142

- ↑ Downham, p. 251

- ↑ Downham, p. 21; Annals of Ulster, s.a. 866; Annals of Clonmacnoise, s.a. 866

- ↑ Annals of Ulster, s.a. 866; Annals of the Four Masters, s.a. 866; Annals of Clonmacnoise, s.a. 866

- ↑ Downham, pp. 21–22

- ↑ Downham, p. 21; Fragmentary Annals of Ireland, § 326

- ↑ Ó Corrain, pp. 32–33; Downham, pp. 21–22; Annals of Clonmacnoise, s.a. 867; Annals of the Four Masters, s.aa. 866, 867; Annals of Ulster, s.a. 866; Fragmentary Annals of Ireland, §§ 329, 349

- ↑ Downham, p. 22

- ↑ Downham, p. 22; Annals of Inisfallen, s.a. 867

- ↑ Ó Corrain, p. 33; Fragmentary Annals of Ireland, § 347

- ↑ Downham, p. 22; Annals of Boyle, § 255; Annals of Clonmacnoise, s.a. 868; Annals of the Four Masters, s.a. 868; Annals of Inisfallen, s.a. 868; Annals of Ulster, s.a. 868; Chronicum Scotorum, s.a. 868

- ↑ Downham, p. 22; Annals of Clonmacnoise, s.a. 869; Annals of Ulster, s.a. 869

- ↑ Downham, p. 22; Annals of Clonmacnoise, s.a. 870; Annals of Ulster, s.a. 870; s.a. 870; Chronicum Scotorum

- ↑ Woolf, pp. 109–110; Annals of Ulster, s.a. 870

- ↑ Woolf, pp. 109–110; Annals of Ulster, s.a. 871

- ↑ Downham, pp. 238–240; Fragmentary Annals of Ireland, § 400

- ↑ Annals of Ulster, s.a. 873

- ↑ Miller, p. 244, note 28

- ↑ Downham, p. 142

- ↑ Pictish Chronicle, p. xxxiv

- 1 2 Hudson

- 1 2 Holman, p. 207

- ↑ Landnámabók, pp. xxviii, 62–63

- ↑ Landnámabók, p. 63

- 1 2 Fragmentary Annals of Ireland, § 400

- ↑ Landnámabók, p. 63; Fragmentary Annals of Ireland, § 292

- ↑ Landnámabók, p. 63; Annals of Ulster, s.a. 875; Annals of the Four Masters, s.a. 868

- ↑ Cogadh Gaedhel re Gallaibh, p. lxxx; Proceedings of the Royal Philosophical Society of Glasgow, Volume 40, p. 96

- ↑ Pictish Chronicle, p. xxxiv; Landnámabók, p. 63

- 1 2 Annals of Ulster, s.a. 863

- 1 2 3 Fragmentary Annals of Ireland, § 347

- ↑ Downham, p. 16, Annals of Ulster, s.a. 867

- ↑ Downham, p. 16

- 1 2 Anglo-Saxon Chronicle, s.a. 878

- ↑ Woolf, p. 95

- ↑ Annals of Ulster, s.a. 875

- ↑ South, p. 87

- ↑ Downham, p. 68

- ↑ Costambeys; Fragmentary Annals of Ireland, § 347

- ↑ Costambeys

- ↑ Anderson, pp. 305–312

- ↑ Smyth, p. 192

- ↑ Downham, pp. 249, 265

- ↑ Annals of the Four Masters; s.a. 868; Annals of Ulster; s.a. 875

Primary sources

- Thorpe, B, ed. (1861). The Anglo-Saxon Chronicle. Rerum Britannicarum Medii Ævi Scriptores. Vol. 1. London: Longman, Green, Longman, and Roberts. Accessed via Internet Archive.

- "Annals of Boyle". Corpus of Electronic Texts (13 February 2010 ed.). University College Cork. 2010. Retrieved 19 December 2014.

- "Annals of the Four Masters". Corpus of Electronic Texts (16 December 2013 ed.). University College Cork. 2013. Retrieved 23 November 2014.

- "Annals of Inisfallen". Corpus of Electronic Texts (23 October 2008 ed.). University College Cork. 2008. Retrieved 18 December 2014.

- "The Annals of Ulster". Corpus of Electronic Texts (15 August 2012 ed.). University College Cork. 2012. Retrieved 23 November 2014.

- Ellwood, Thomas, ed. (1898). The Book of the Settlement of Iceland. Kendal: T. Wilson. Accessed via Internet Archive.

- Skene, William Forbes, ed. (1867). Chronicles of the Picts, chronicles of the Scots, and other early memorials of Scottish history. Edinburgh: HM General Register House. Accessed via Internet Archive.

- "Chronicon Scotorum". Corpus of Electronic Texts (24 March 2010 ed.). University College Cork. 2010. Retrieved 26 November 2014.

- Todd, JH, ed. (1867). Cogad Gaedel re Gallaib: The War of the Gaedhil with the Gaill. London: Longmans, Green, Reader, and Dyer. Accessed via Internet Archive.

- "Fragmentary Annals of Ireland". Corpus of Electronic Texts (5 September 2008 ed.). University College Cork. 2008. Retrieved 29 November 2014.

- Murphy, D, ed. (1896). The Annals of Clonmacnoise. Dublin: Royal Society of Antiquaries of Ireland. Accessed via Internet Archive.

Secondary sources

- Anderson, Alan Orr (1922). Early Sources of Scottish History A.D 500–1286. Vol. 1. Stamford: Paul Watkins. ISBN 1-871615-03-8. Accessed via Internet Archive.

- Clarke, Howard B.; Ní Mhaonaigh, Máire; Ó Floinn, Raghnall (1998). Ireland and Scandinavia in the Early Viking Age. Four Courts Press. ISBN 978-1-85182-235-5.

- Costambeys, Marios (2004). "Hálfdan (d. 877)". Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (online ed.). Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/49260. Retrieved 20 December 2014. (Subscription or UK public library membership required.) Subscription or UK public library membership required.

- Crawford, Barbara (1987). Scandinavian Scotland. Leicester: Leicester University Press. ISBN 0-7185-1282-0.

- Downham, Clare (2007). Viking Kings of Britain and Ireland: The Dynasty of Ívarr to A.D. 1014. Edinburgh: Dunedin Academic Press. ISBN 978-1-903765-89-0.

- Duffy, Seán (15 January 2005). Medieval Ireland: An Encyclopedia. Routledge. ISBN 978-1-135-94824-5.

- Helle, Knut, ed. (2003). The Cambridge History of Scandinavia. Volume 1: Prehistory to 1520. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-521-47299-7.

- Holman, Katherine (2003). Historical dictionary of the Vikings. Lanham, Maryland: Scarecrow Press. ISBN 978-0-8108-4859-7.

- Hudson, Benjamin T. (2004). "Óláf the White (fl. 853–871)". Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (online ed.). Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/49263. Retrieved 5 December 2014. (Subscription or UK public library membership required.) Subscription or UK public library membership required.

- Miller, Molly. "Amlaíb trahens centum". Scottish Gaelic Studies. 19: 241–245.

- Ó Corrain, Donnchad (1998). "The Vikings in Scotland and Ireland in the Ninth Century" (PDF). Peritia. 12: 296–339. doi:10.1484/J.Peri.3.334.

- O Croinin, Daibhi (16 December 2013). Early Medieval Ireland, 400–1200. Routledge. ISBN 978-1-317-90176-1.

- Proceedings of the Royal Philosophical Society of Glasgow. Vol. 40. Royal Philosophical Society. 1913.

- Radner, Joan. "Writing history: Early Irish historiography and the significance of form" (PDF). Celtica. 23: 312–325. Archived from the original (PDF) on 23 September 2015.

- Smyth, Alfred P. (1989). Warlords and Holy Men: Scotland AD 80–1000. Edinburgh University Press. ISBN 978-0-7486-0100-4.

- South, Ted Johnson (2002). Historia de Sancto Cuthberto. Boydell & Brewer. ISBN 978-0-85991-627-1.

- Woolf, Alex (2007). From Pictland to Alba: 789–1070. Edinburgh University Press. ISBN 978-0-7486-1234-5.

External links

- CELT: Corpus of Electronic Texts at University College Cork. The Corpus of Electronic Texts includes the Annals of Ulster and the Four Masters, the Chronicon Scotorum and the Book of Leinster as well as Genealogies, and various Saints' Lives. Most are translated into English, or translations are in progress.