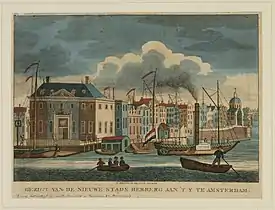

The steamboat Mercurius of the ASM, leaving Amsterdam for Zaandam, c. 1830. | |

| Industry | Shipping company |

|---|---|

| Founded | 1825 |

| Defunct | 1877[1] |

| Headquarters | , |

Area served | Zuiderzee, Hamburg |

Key people | Paul van Vlissingen |

Amsterdamsche Stoomboot Maatschappij was an early Dutch steam shipping company.

Context and Foundation of the ASM

Early initiatives for steam navigation

In September 1816 the British steamboat Defiance visited Amsterdam, but met little local enthusiasm.[2] The lack of support for steam navigation in Amsterdam is explained by that it threatened the vested interests of the Amsterdam merchants. There were however also genuine concerns about the net price for transport getting higher, and about the continuity of service. [3]

People in Rotterdam and in the national government did see opportunities, and so the predecessor of the Nederlandsche Stoomboot Maatschappij (NSM) was founded in Rotterdam in 1822.[3]

In the summer of 1823 Eduard Taylor living at Ridderoord in Lage Vuursche asked Amsterdam for a concession for two shipping lines. One from Amsterdam to Utrecht, and one from Amsterdam to Lemmer across the Zuiderzee in Friesland. In June 1824 Taylor's first steamboat Mercurius was launched by the Hollandia shipyard of Van Swieten. The engines were constructed from British parts put together in Amsterdam, because NSM and Cockerill tried to monopolize the Dutch market for steamboats.[3] When Mercurius proved unsuitable for use on canals, she was put to use on a line between Amsterdam and Zaandam.[4]

A plan that did get the immediate support of the Amsterdam municipality was that for a towing service on the Noordhollandsch Kanaal. Thomas Zurmühlen and Diederik Liedermooy wanted to build and operate two steam tugs for this purpose. This plan was less threatening to vested interests, and ensured that ships sailing to far off destinations would loose less time on the canal.[5]

Also in the summer of 1823, Leonard de Vijver requested permission for a steam shipping line between Amsterdam and Harlingen. He died before his plans could be executed, but it led to the foundation of the shipping company Harlinger Stoomboot Reederij (Harlingen Steamboat Company).[6] This company came under the direction of Paul van Vlissingen (1797-1876) and his brother Frits. In February 1825 the Van Vlissingen brothers, as directors of the Harlingen Steamboat Company asked permission to create many local steam shipping lines, and two lines to Hamburg and London. The latter lines required more costly, sea going ships. In May 1825, the permission came in. It had the usual requirement that the steam engines had to be made in the Netherlands.[7]

Foundation of the Amsterdamsche Stoomboot Maatschappij

The attempts to found a steamboat company in Amsterdam received more support when a foreign (i.e. Rotterdam) company tried to establish lines from Amsterdam. In June 1824 the NSM decided to open a line from Amsterdam to Hamburg.[8] In May 1825 the steamship De Batavier was laid down by Fop Smit for this line.[9] This obviously threatened the control of the Amsterdam merchants over local shipping.

The much larger scale of the new plans required the foundation of a new company. Paul van Vlissingen contacted Diederik Bernard Liedermooy to help him establish this new company. Together they got the support of many Amsterdam merchants, and succeeded in establishing the Amsterdamsche Stoomboot Maatschappij (ASM) in late April 1825.[10] The new Amsterdamsche Stoomboot Maatschappij even acquired a capital of 500,000 instead of only 300,000 guilders. This allowed ASM to expand the scope of its operations. Instead of only operating from Amsterdam to Hamburg and London, it now also immediately opened some local lines in the Netherlands. The statute of the ASM got approved on 18 May 1825.[11]

Early years

Early operations

Only a few months after her foundation, ASM sent the steamboat De Onderneming (enterprise) from Amsterdam to Hamburg on 25 July 1825. This was the ex English steamboat Monarch of 76 net tons and 36 hp, which had been acquired by ASM for 75,753 guilders.[12] These trips first went from Amsterdam over the Zuiderzee to Harlingen. From there the boats went to the North Sea crossing between Vlieland and Terschelling. The passenger fares were high: First class rate was 60 guilders, second class 35. Freight was carries at 60 guilders for about 2 tons. It was also possible to just go to Harlingen for 7 guilders.[13]

The first directors of the company were the two Van Vlissingen brothers and Mr. Liedermoooy. Apart from buying De Onderneming, one of their first acts was to order two steamboats and two steamships, all of them paddle steamers, at the Hollandia shipyard of Mr. van Swieten, who was already constructing the steamboat Prins Frederik for the Harlingen Steamboat Line. At the time, one of the challenges for these ships was that their draft had to be limited. While they could pass the Noordhollandsch Kanaal, they were not allowed to make regular use of the canal, because the authorities did not want them to damage the canal dykes. Another problem was the construction of the machines. Cockerill was totally occupied with orders by NSM. Therefore, some of the engines were ordered in Couvin, near the French border.[13]

Lines to Zaandam and Harderwijk

In July 1826 Mercurius started a line between Amsterdam and Zaandam. She had obviously been acquired by the ASM. Twice a day she left from the Keulsche Waag in Amsterdam for the ASM pier in Zaandam.[14] By the request of the Amsterdam municipality, an agreement had been reached with the Zaandam skippers for a combined service. This agreement would turn this profitable line into one that would steadily loose money for some years.[15]

In November 1826 IJssel opened a line to Harderwijk across the Zuiderzee. It would later be expanded to Kampen.[16]

The steamships get operational

In November 1826 ASM's two steamships were finished. Willem I was 150 feet long, measured 595 tons, and had 120 hp machines by Maudslay. She could transport 70 lasts and 70 passengers. The Beurs van Amsterdam was somewhat smaller, measured 528 tons, and had equally powerful engines. The two steamships had size comparable to the size of De Batavier of 600 tons.[17] In 1827 Willem I was used on the route to Hamburg. Beurs van Amsterdam was used for the London line.[18]

The commissioning of the steamships left De Onderneming without a fixed purpose. ASM then tried to sell her to the government for 80,000 guilders, but a government report valued her at no more than 25,000 guilders.[19]

By the end of 1826 ASM proved to have been mistaken in the costs of her operations. De Onderneming, Mercurius and IJssel together cost 200,000 guilders to acquire. Another 100,000 guilders were tied up in stores. However, in view of the extra 200,000 guilders that had been raised, the expansion of the ASM plans was more or less covered. The real problem was that the construction and operation of the steamships that were getting finished. Their cost had been grossly underestimated. They had to be coppered, and proved to require heavier engines. The shipyard Van Swieten had also miscalculated, and got in financial trouble. ASM then had to finish these ships under her own direction. By October 1826 ASM had only 47,000 guilders left, and applied to the government for support. It got a loan of 150,000 guilders at 3%, probably because NSM had also received support. This had to be repaid in 6 years.[15]

ASM almost collapses (1827-1828)

In 1827, its first year of operation, the line to Hamburg was profitable and brought in a gross profit of 20,000 guilders. The line to London plied by Beurs van Amsterdam, cost about as much as it brought in. It would be terminated after only one year.[20] In 1827 De Onderneming would be used for a line between Ostend and Margate.[21] In the end, this line was not successful, but De Onderneming still earned 8,000 guilders in 1827.[19] The smaller boats all led to losses. Over 1827, the total operational profit of 10,588 guilders was cancelled by 'administrative costs' of 18,492 guilders.[19] The salary for the directors had been fixed at 6% of revenue.[22]

On 26 December 1827 ASM again applied to the government for help. It met with a negative response, because ASM had not repaid the first installment of the previous loan, and lacked capital.[23] The company then took a private loan of 80,000 guilders at very disadvantageous terms. In 1828 both steamships were used on the line to Hamburg. In 1828 an attempt was made to use De Onderneming from Amsterdam to Harlingen via Enkhuizen, but this was not successful. The Hamburg line was again profitable, but overall profit was only 4,000 guilders. This was not sufficient to repay the installment of the government loan of 25,000 guilders and that of the private loan at 27,000 guilders.[23]

In 1829 Paul van Vlissingen proposed that ASM would concentrate on the Hamburg line, and sell the smaller vessels. Administrative costs would be limited to 4,000 guilders, and his own salary would be limited to 8% of the net profit. Meanwhile the other directors had resigned. The government then agreed to help ASM again, or at least not to require repayment of the loans. In exchange, the government required that a government commissioner would see to the proper management of ASM.[24]

In March 1829 ASM then tried to sell De Onderneming, IJssel and Mercurius.[25] The attempt to sell these ships failed, probably in part because people thought that in the end, ASM would be forced to sell at any price.[26]

ASM is saved by the government (1829)

After the failure to sell the smaller vessels, Van Vlissingen again appealed to the government in May 1829. He noted that the line to Hamburg had become even more profitable in 1828.[26] After a lot of haggling, the government helped ASN by taking shares for 150,000 guilders, and by converting the 150,000 guilders loan in shares, making her the biggest shareholder, with shares worth 300,000 guilders.[27]

The Belgian Revolution 1830

In 1830 the ASM decided to employ the Beurs van Amsterdam to extend the line from Amsterdam to Hamburg to Petersburg.[28][29] After the Belgian Revolution, the Beurs van Amsterdam wanted to steam to Petersburg again, but now the Russian government had given a monopoly to a Russian company.[30] The Beurs van Amsterdam was then used to operate a line from Rotterdam to Dunkirk. This made sense, because the Dutch - Belgian border was closed.[31] De De Onderneming, renamed Graaf Cancrin was also busy in the Baltic for some years.[31]

Van Vlissingen en Dudok van Heel (1826)

As most other early steam shipping companies, ASM wanted to have its own repair shop. This was founded by Paul van Vlissingen by his own means in late 1826. He offered the workshop to the ASM, but its shareholders declined the offer in 1828. Their reasoning was that the existence of the repair shop was necessary for ASM, but that owning it would hinder the workshop in working for third parties, which would in turn force ASM to maintain it. It then became owned by a partnership between Paul van Vlissingen and Mr. Dudok van Heel, and was named Van Vlissingen en Dudok van Heel. It would develop into a shipbuilding company that would operate with much more success than the ASM itself. It later became known as Koninklijke Fabriek van Stoom- en andere Werktuigen, and still later as Werkspoor.[32]

Steady operations

Regular business (1833)

After the 1832 Anglo-French blockade of the Dutch coast was lifted, the operations of the ASM got a more regular character. In 1833 a new contract with the Zaandam skippers finally made the Zaandam line profitable. The engines of IJssel were sold to the NSM for 19,000 guilders, and the vessel itself was changed into a barge. However, the Beurs van Amsterdam suffered a costly disaster when she was stranded and recovered.[33] In 1836 Willem I was sold to the government. Soon after, she was lost near the Lucipara Islands in the Dutch East Indies.[34]

Dubious accounting

ASM applied some rather dubious accounting practices. Ships were kept on the balance sheet for their cost price, and no depreciation was applied. Therefore, when the engines of IJssel were sold, the equity of the company, based on a share capital of 800,000 guilders, decreased to 732,656 guilders. Meanwhile the sale of the engines was booked as a profit, and used to pay a dividend. When Willem I was sold, this practice led to a sudden drop in the equity of the company from 732,000 to 695,000 guilders, because the book value of Willem I was much higher than the price for which she was sold. The practice to nevertheless pay a small dividend was also continued. This practice to pay a dividend from capital was generally forbidden, because creditors doing business with a public company had to rely on that company having assets. The government was not amused by the practices of the ASM, and constantly protested, but equity of the ASM was nevertheless reduced to 539,790 by 1854.[35]

Further operations

In 1834 the Dutch government urged the Amsterdam Chamber of Commerce to further steam navigation. The answer of the chamber gives some explanation about why this did not happen at the time. It stated that the higher cost of steamships compared to sailing ships, meant that the former were suitable only where there was a high passenger traffic, or much traffic in high value or urgent shipments. Therefore, Rotterdam - London, and Amsterdam - Hamburg were profitable lines. Lines from Amsterdam to the south were practically impossible, because of the long detour over the Zuiderzee. The only option that the chamber saw, was a line to Hull.[37]

In 1835, Prins Frederik was bought from the Harlingen Line for 85,000 guilders, and this simply stopped to operate. Prins Frederik was then used to open a line from Lübeck to Stockholm. However, an English competitor was immediately dispatched, and so freight was lowered by half, making the line unprofitable. Also in 1835 Graaf Cancrin returned to Amsterdam and was lengthened and renamed Prinses van Oranje. As such, she did well. In 1839, a new Willem I was completed.[38]

People from Harlingen reacted to the closure of the Harlingen line by making plans to create their own shipping line to Amsterdam. The ASM then asked for permission to use Prins Frederik for an ASM line to Harlingen. The government gave this permission in May 1837, and that year ASM operated her line to Harlingen. The people from Harlingen then agreed to found a new shipping line. ASM would manage it, and take shares for 24,000 guilders. A personal profit for Van Vlissingen was that it ordered a new steamboat at Van Vlissingen and Dudok van Heel.[38]

The final peace with Belgium, concluded in the Treaty of London (1839), was not good for ASM. The line to Dunkirk, serviced by Prinses van Oranje, quickly became unprofitable. Prinses van Oranje was then sent to Hull, but proved too weak to operate on that line. Prins Frederik would also fail to make a profit there. In 1849 she was turned into a dumb barge.[39]

In 1846 Beurs van Amsterdam and Willem I were plying the route to Hamburg. The line to Dunkirk had been reopened by Prinses van Oranje, and the line to Zaandam was serviced by a new, iron Mercurius. Accounting had been improved allowing for reserves to renew the fleet. In 1848 a new iron ship De Stoomvaart had been built with use of the engines of Beurs van Amsterdam.[40]

The Screw Schooner Company

In 1848 Paul van Vlissingen made a new attempt to found a shipping line to England.[41] There were multiple reasons for this new attempt. In 1846, the Corn Laws had been cancelled. It was also known that the Navigation Acts would be cancelled in 1849. Furthermore, the railroad from Amsterdam had finally reached the Rhine.[42] Another reason was the introduction of iron hulls for sea-going ships and of the screw as a means propulsion. In the Netherlands this happened when L. Smit en Zoon launched the iron screw schooner Industrie in 1847.

Paul van Vlissingen thus founded the Stoomschroefschooner Reederij (Steam screw schooner line)) to operate a line to London. The British St Petersburg Steamship Company had opened a line between London and Amsterdam in October 1847.[43] When it heard about Van Vlissingen's plans it threatened that it would open a line from Amsterdam to Hamburg. In March 1849 the Stoomschroefschooner Reederij got its concession.[44] The Gouverneur van Ewijck, built by Van Vlissingen en Dudok van Heel, was one of the ships used on the London line in 1849.[45]

The line to England was not profitable. For ASM the result was disastrous, because the St Petersburg Steamship Company indeed opened a line between Amsterdam and Hamburg, driving freight prices to an all-time low. The result of Van Vlissingen's action was that ASM had to pay the Stoomschroefschooner Reederij to move her ships away from the London line, so the St Petersburg Steamship Company would remove her ships from the Hamburg line. The deal made ASM profitable again. It allowed her to replace the old Prinses van Oranje with an iron Prins van Oranje. A few years later, the Stoomschroefschooner Reederij would operate a line to Hull. It was dissolved in 1862.[46]

Sudden expansion of the ASM (1855)

In 1846 the Fonds der Nationale Nijverheid, a foundation for the development of Dutch industry, had been disbanded. The finance ministry had been ordered to liquidate its assets, amongst these the 300,000 guilder share in ASM.[47] In December 1854, this finally led to the sale of these shares to Paul van Vlissingen for 120,000 guilders, or 40% of their nominal value.[48]

In 1855 the deal led to a new financial structure of ASM. New preference shares were created for 100,000 guilders. These would receive 5% dividend, and not more, before others. ASM also placed bonds for 250,000 guilders at 4.5%. With this money she acquired the small ships Amsterdam, Harburg, Jonge Paul, and Jonge Marie. In 1857, 384,000 guilders of shares were sold. With this, ASM acquired the steamer Kroonprinses Louise and 3/4 of the Screw Schooner Company. In 1857, the ASM had lines to Saint Petersburg, Hamburg, Harburg, Stettin, Dunkirk, Zaandam, Stockholm, and Hull.[48]

The sudden and unexpected growth of the ASM raised some suspicions about the government having sold too cheap. In December 1857 Van Vlissingen argued that if the government had continued as a 300,000 guilder shareholder with a special commissioner, the sudden growth would not have taken place.[49] However that might be, in June 1860, the general shareholders meeting decided to half the nominal value of the 862 shares of 1,000 guilders each.[50]

Towards the end

ASM under the direction of C. Gilhuys

The management of the ASM would gradually come to Van Vlissingen's son in law C. Gilhuys. In 1853 he first acted as his delegate. Van Vlissingen's interest in Van Vlissingen en Dudok van Heel was managed by his son Paul C. van Vlissingen.[50]

Competition by KNSM

In 1856 the Koninklijke Nederlandse Stoomboot-Maatschappij (KNSM) was founded. KNSM was not a prestigious company, but is soon put immense pressure on ASM. In 1857 AMS had to agree on freight prices to Saint Petersburg. In 1863 ASM negotiated for KNSM to leave the Hamburg line, but had to leave that to Stettin, and had to share the line to Königsberg with KNSM.[50]

ASM now slowly faded, as no new ships were ordered, and the old ones continued to serve. By 1877 all that was left were two screw ships (Stoomvaart and Amsterdam), and two paddle steamers (Willem I and Prins van Oranje). The first three ships serviced an ever less frequent line to Hamburg. The Prins van Oranje served on the Dunkirk line, which continued to be profitable till the 1870s.[51]

The end (1877)

After Paul van Vlissingen's death in 1876, C. Gilhuys was formally appointed as chairman of ASM.[52] On 10 March 1877 a general shareholders meeting was held, with 216 shares represented. The new director proposed to take a loan of 150,000 guilders, but the shareholders rejected this plan. They then decided to liquidate the company.[1]

The assets of ASM were bought by the Rotterdam company P.A. van Es and Co., which in March 1877 paid 135,000 guilders for the four steamships, a barge, and a warehouse in Dunkirk. In turn P.A. van Es sold Prins van Oranje and the line to Dunkirk to Joh. Ooms Jzn., who was already active in the area. P.A. van Es and Co. then came in very serious competition with the KNSM, but managed to hold on to part of the Hamburg operation. Of the old ships, Willem I was sold in 1885, Amsterdam in 1893, and De Stoomvaart in 1898.[51]

Some ships of the Amsterdamsche Stoomboot Maatschappij

| Ship | Type | Launched | Size in ton | Shipyard | Engines | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| De Onderneming (ex-Monarch)[53] | Steamboat | 1 October 1822[54] | 76,[53] 100t gross[54] | James Duke, Dover[54] | Maudslay | Acquired second hand |

| Mercurius[53] | Steamboat | 1 June 1824 | 84 | Hollandia shipyard | Galloway | Acquired second hand |

| Prins Frederik[53] | Steamboat | 17 May 1825 | 230 | Hollandia shipyard | Galloway | Acquired second hand |

| De IJssel[53] | Steamboat | 3 June 1826 | 182 | Hollandia shipyard | Cockerill | |

| Willem de Eerste[53] | Steamship | 4 August 1826 | 595 | Hollandia shipyard | Maudslay | Sold in 1836 |

| Beurs van Amsterdam[53] | Steamship | 4 August 1826 | 528 | Hollandia shipyard | Maudslay | |

| Willem I[55] | Steamship | 10 August 1838 | 487, 258 net | De Haan shipyard, Amsterdam | Van Vlissingen en Dudok van Heel | Renamed Jonge Paul 1856, sunk 1863[55] |

| De Stoomvaart[36] | Steamship | 8 August 1848 | 507 net | Van Vlissingen en Dudok van Heel | Van Vlissingen en Dudok van Heel | Iron ship, broken up 1906[36] |

References

Citations

- 1 2 "Vervolg van het hoofdblad". Provinciale Noordbrabantsche en 's Hertogenbossche courant. 15 March 1877.

- ↑ Blink 1922, p. 129.

- 1 2 3 Blink 1922, p. 130.

- ↑ Blink 1922, p. 131.

- ↑ De Boer 1921, p. 7.

- ↑ De Boer 1921, p. 13.

- ↑ De Boer 1921, p. 15.

- ↑ De Boer 1921, p. 5.

- ↑ "Rotterdam den 10 Mei". Rotterdamsche courant. 12 May 1825.

- ↑ "Nederlanden". Opregte Haarlemsche Courant. 28 April 1825.

- ↑ "Advertisements". Opregte Haarlemsche Courant. 31 May 1825.

- ↑ Hermes 1828, p. 60.

- 1 2 Blink 1922, p. 132.

- ↑ "Advertisements". Opregte Haarlemsche Courant. 22 July 1826.

- 1 2 De Boer 1921, p. 23.

- ↑ "Advertisements". Opregte Haarlemsche Courant. 21 November 1826.

- ↑ Hermes 1828, p. 58.

- ↑ "Advertisements". Opregte Haarlemsche Courant. 7 April 1827.

- 1 2 3 De Boer 1921, p. 26.

- ↑ "Advertisements". Opregte Haarlemsche Courant. 12 June 1828.

- ↑ "Advertisements". Leydse courant. 4 April 1827.

- ↑ De Boer 1921, p. 18.

- 1 2 De Boer 1921, p. 27.

- ↑ De Boer 1921, p. 29.

- ↑ "Advertisements". Opregte Haarlemsche Courant. 7 March 1829.

- 1 2 De Boer 1921, p. 31.

- ↑ De Boer 1921, p. 37.

- ↑ De Boer 1921, p. 42.

- ↑ "Advertisements". Algemeen Handelsblad. 21 April 1830.

- ↑ De Boer 1921, p. 43.

- 1 2 De Boer 1921, p. 44.

- ↑ Tindal & Swart 1848, p. 571.

- ↑ De Boer 1921, p. 45.

- ↑ De Boer 1921, p. 47.

- ↑ De Boer 1921, p. 46.

- 1 2 3 "Stoomvaart (de) - ID 8358". Stichting Maritiem Historische Databank. Stichting Maritiem Historische Databank. Retrieved 2 December 2022.

- ↑ De Boer 1921, p. 59.

- 1 2 De Boer 1921, p. 62.

- ↑ De Boer 1921, p. 64.

- ↑ De Boer 1921, p. 66.

- ↑ "Advertisements". Algemeen Handelsblad. 19 July 1848.

- ↑ De Boer 1921, p. 67.

- ↑ "Advertisements". Algemeen Handelsblad. 21 October 1847.

- ↑ De Boer 1921, p. 68.

- ↑ Lintsen 1993, p. 76.

- ↑ De Boer 1921, p. 69.

- ↑ De Boer 1921, p. 72.

- 1 2 De Boer 1921, p. 74.

- ↑ De Boer 1921, p. 75.

- 1 2 3 De Boer 1921, p. 78.

- 1 2 De Boer 1921, p. 81.

- ↑ "Binnenland". De Tijd, godsdienstig-staatkundig dagblad. 12 April 1876.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 Hermes 1828, p. 58-61.

- 1 2 3 "Packet Service I to 1854". The Dover Historian. The Dover Historian. 21 March 2015. Retrieved 2 December 2022.

- 1 2 "Willem de Eerste - ID 8385". Stichting Maritiem Historische Databank. Stichting Maritiem Historische Databank. Retrieved 2 December 2022.

Bibliography

- Blink, H. (1922), "De economische toestand van Amsterdam in de negentiende eeuw in verband met de ontwikkeling der Stoomvaart", Tijdschrift voor Economische Geografie, Vereniging voor Economische Geographie, p. 118-136

- De Boer, M.G. (1921), Geschiedenis der Amsterdamsche stoomvaart, vol. I, Scheltema & Holkema's Boekhandel, Amsterdam

- De Boer, M.G. (1927), Honderd jaar machine-industrie op Oostenburg, Amsterdam, Druk de Bussy, Amsterdam

- "Iets over stoom-vaartuigen", De Nederlandsche Hermes, tijdschrift voor koophandel, zeevaart en (in Dutch), M. Westerman, Amsterdam, no. 8, pp. 53–63, 1828

- Lintsen, H.W. (1993), Geschiedenis van de techniek in Nederland. De wording van een moderne samenleving 1800-1890. Deel IV

- Lodder, Jan W. (1982), "Stoomschepen op de Zuiderzee in zijaanzichten", Het Peperhuis, Vereniging vrienden van het Zuiderzeemuseum, p. 21-33

- Tindal, G.A.; Swart, Jacob (1848), "Fabriek van Stoom- en ander Werktuigen", Verhandelingen en berigten betrekkelijk het zeewezen (in Dutch), Wed. G. Hulst van Keulen, Amsterdam, pp. 571–578