An amygdala hijack is an emotional response that is immediate, overwhelming, and out of measure with the actual stimulus because it has triggered a much more significant emotional threat.[1] The term, coined by Daniel Goleman in his 1996 book Emotional Intelligence: Why It Can Matter More Than IQ,[2] is used by affective neuroscientists and is considered a formal academic term. The amygdala is made up of two small, round structures located closer to the forehead than (anterior to) the hippocampi, near the temporal lobes. The amygdalae are involved in detecting and learning which parts of our surroundings are important and have emotional significance. They are critical for the production of emotion. They are known to be very important for negative emotions, especially fear.[3] Amygdala activation often happens when we see a potential threat. The amygdala uses our past, related memories to help us make decisions about what is currently happening.[4]

Definition

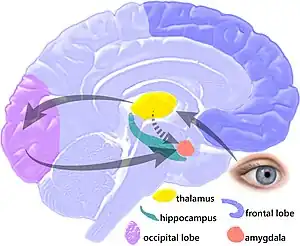

The output of sense organs is first received by the thalamus. Part of the thalamus' stimuli goes directly to the amygdala or "emotional/irrational brain", while other parts are sent to the neocortex or "thinking/rational brain". If the amygdala perceives a match to the stimulus, i.e., if the record of experiences in the hippocampus tells the amygdala that it is a fight, flight or freeze situation, then the amygdala triggers the HPA (hypothalmic–pituitary–adrenal) axis and "hijacks" or overtakes rational brain function.[5]

This emotional brain activity processes information milliseconds earlier than the rational brain, so in case of a match, the amygdala acts before any possible direction from the neocortex can be received. If, however, the amygdala does not find any match to the stimulus received with its recorded threatening situations, then it acts according to the directions received from the neocortex. When the amygdala perceives a threat, it can lead that person to react irrationally and destructively.[6]

Goleman states that emotions "make us pay attention right now—this is urgent—and gives us an immediate action plan without having to think twice. The emotional component evolved very early: Do I eat it, or does it eat me?" The emotional response "can take over the rest of the brain in a millisecond if threatened".[7][8] An amygdala hijack exhibits three signs: strong emotional reaction, sudden onset, and post-episode realization if the reaction was inappropriate.[7]

Goleman later emphasized that "self-control is crucial ... when facing someone who is in the throes of an amygdala hijack"[9] so as to avoid a complementary hijacking—whether in work situations, or in private life. Thus for example "one key marital competence is for partners to learn to soothe their own distressed feelings ... nothing gets resolved positively when husband or wife is in the midst of an emotional hijacking".[10] The danger is that "when our partner becomes, in effect, our enemy, we are in the grip of an 'amygdala hijack' in which our emotional memory, lodged in the limbic center of our brain, rules our reactions without the benefit of logic or reason ... which causes our bodies to go into a 'fight or flight' response."[11]

Non-distressing hijack

Goleman points out that "not all limbic hijackings are distressing. When a joke strikes someone as so uproarious that their laughter is almost explosive, that, too, is a limbic response. It is at work also in moments of intense joy."[12]

He also cites the case of a man strolling by a canal when he saw a girl staring petrified at the water. "[B]efore he knew quite why, he had jumped into the water—in his coat and tie. Only once he was in the water did he realize that the girl was staring in shock at a toddler who had fallen in—whom he was able to rescue."[13]

Creative hijack

Links between creativity and mental health have been extensively discussed and studied by psychologists and other researchers for centuries. Parallels can be drawn to connect creativity to major mental disorders including bipolar disorder, schizophrenia, major depressive disorder, anxiety disorder, OCD and ADHD. For example, studies have demonstrated correlations between creative occupations and people living with mental illness. There are cases that support the idea that mental illness can aid in creativity, but it is also generally agreed that mental illness does not have to be present for creativity to exist.[14][15]

Emotional relearning

Joseph E. LeDoux was positive about the possibility of learning to control the amygdala's hair-trigger role in emotional outbursts. "Once your emotional system learns something, it seems you never let it go. What therapy does is teach you how to control it—it teaches your neocortex how to inhibit your amygdala. The propensity to act is suppressed, while your basic emotion about it remains in a subdued form."[16]

See also

References

- ↑ "Conflict and Your Brain aka The Amygdala Hijacking" (PDF). Retrieved 2010-04-06.

- ↑ Nadler, Relly. "What Was I Thinking? Handling the Hijack" (PDF). Retrieved 2019-04-15.

- ↑ LeDoux, Joseph E. (1995). "Emotion: Clues from the Brain". Annual Review of Psychology. 46 (1): 209–235. doi:10.1146/annurev.ps.46.020195.001233. ISSN 0066-4308. PMID 7872730.

- ↑ Breiter, Hans C; Etcoff, Nancy L; Whalen, Paul J; Kennedy, William A; Rauch, Scott L; Buckner, Randy L; Strauss, Monica M; Hyman, Steven E; Rosen, Bruce R (1996). "Response and Habituation of the Human Amygdala during Visual Processing of Facial Expression". Neuron. 17 (5): 875–887. doi:10.1016/S0896-6273(00)80219-6. PMID 8938120. S2CID 17284478.

- ↑ Bedard, Moe (2021-10-31). "Battle for the Noosphere: How the human mind can be highjacked via the amygdla". Gnostic Warrior. Retrieved 2022-09-15.

- ↑ Freedman, Joshua. "Hijacking of the Amygdala" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on November 22, 2009. Retrieved 2010-04-06.

- 1 2 Horowitz, Shell. "Emotional Intelligence – Stop Amygdala Hijackings" (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on 2021-05-11. Retrieved 2010-04-06.

- ↑ Hughes, Dennis. "Interview with Daniel Goleman". Retrieved 2010-04-06.

- ↑ Daniel Goleman, Working with Emotional Intelligence (1999) p. 87

- ↑ Goleman, Emotional Intelligence p. 144

- ↑ Rita DeMaria et al., Building Intimate Relationships (2003) p. 57

- ↑ Goleman, Emotional Intelligence p. 14

- ↑ Goleman, Emotional Intelligence p. 17

- ↑ Kyaga, Simon; Landén, Mikael; Boman, Marcus; Hultman, Christina M.; Långström, Niklas; Lichtenstein, Paul (January 2013). "Mental illness, suicide and creativity: 40-year prospective total population study". Journal of Psychiatric Research. 47 (1): 83–90. doi:10.1016/j.jpsychires.2012.09.010. ISSN 1879-1379. PMID 23063328.

- ↑ Musgrave, George; Gross, Sally Anne (2020-09-29). Can Music Make You Sick?. University of Westminster Press. doi:10.16997/book43. ISBN 978-1-912656-62-2. S2CID 224842613.

- ↑ Goleman, Daniel (August 15, 1989). "Brain's Design Emerges As a Key to Emotions". The New York Times.