_of_Moreton_Corbet_Shropshire.jpg.webp)

_of_Moreton_Corbet_Shropshire.jpg.webp)

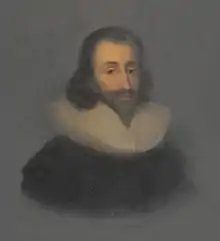

Sir Andrew Corbet (1580–1637) of Moreton Corbet, Shropshire, was an English politician who sat in the House of Commons at various times between 1624 and 1629. A Puritan sympathiser, he at first supported the government but became an increasingly vocal opponent of King Charles I's policies and ministers.

Background and education

He was the son of[2] Sir Vincent Corbet (d.1623), of Moreton Corbet, by his wife Frances[3] Humfreston, a daughter of William Humfreston of Humfreston in the parish of Albrighton, near Bridgnorth, in Shropshire.

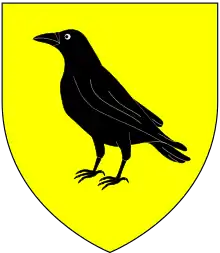

Sir Vincent was the son of Sir Andrew Corbet (1522-1578) of Moreton Corbet. The Corbets traced their lineage and connection with Shropshire back to the Norman Conquest,[4] and were important marcher lords in the Middle Ages. They emerged in the 16th century as Shropshire's leading gentry family in a county without resident aristocracy,[5] but were never ennobled.

The Corbets had reached the height of their power and influence under the first Sir Andrew, who died in 1578. He and his wife had six sons,[6] apparently assuring the succession and the continuing power of the dynasty. However, their eldest son, Robert Corbet, died of bubonic plague after less than five years as head of the family, leaving two daughters but no sons to succeed him.[7] His heir, his brother, Richard Corbet was a spendthrift who left debts of about £6000 but no children.[8] Vincent Corbet, the youngest and last surviving son inherited a difficult situation, which he strove to stabilise.

The second Andrew Corbet was baptised at Moreton Corbet on 28 August 1580,[9] and was presumably born earlier the same month.

Andrew Corbet's prospects, as the heir of a sixth son, would not have seemed especially bright and he was given as full an education as possible to secure his future. He was educated first at Shrewsbury School, then famous for its blend of Calvinist and humanist education,[10] which involved extensive use of drama. His was the second generation of Corbets to attend the school, and his great-uncle Reginald Corbet, as recorder of Shrewsbury had played an important part in the agitation which led to its establishment, funded by property from the Dissolution of the Monasteries.

Corbet then attended Oxford University. However, his college was not St John's, which had a particularly close link with his school, but Queen's, from which he matriculated on 20 June 1602.[9] He was then given a legal education for two years at Lincoln's Inn.

Landowner

Andrew's father, Vincent Corbet, had inherited vast estates when his brother Richard died in 1606: 12,600 acres in Shropshire,[2] concentrated mainly between the county town and Market Drayton, on the north-western edge, as well as 7,000 acres in Buckinghamshire, Northamptonshire and Oxfordshire. However, there were major problems. Richard's debts were huge, and he left the new Elizabethan building at Moreton Corbet Castle, begun by Robert, still unfinished after a quarter century or more in construction. Although most of the estates were in fee tail male, preventing their dispersal, substantial lands were not. This meant that Robert Corbet's surviving daughter, Elizabeth, and her husband, Sir Henry Wallop could mount claims to them, and in some cases had already taken possession. Most pressing of all, Richard's widow, Judith Austin, a forceful woman, three-times-married and very wealthy,[11] held large estates as her jointure. Worse still, Judith had potential claims on more, as the improvident Richard had made up her jointure in questionable ways, acknowledging as much in his rambling will.[12]

Vincent came to an agreement with Wallop on Elizabeth's marriage settlement. The problem of Judith's future claims was neutralised by arranging the marriage of Andrew to Judith's eldest daughter, Elizabeth Boothby.[2] The marriage settlement is dated 6 January 1607. Andrew and his wife settled at Acton Reynald Hall, to the west of Moreton Corbet. Vincent was knighted in July 1607 at Greenwich[13] and went on to complete the new house at Moreton Corbet, although he had little public presence and was never a knight of the shire. Andrew was knighted on 25 August 1617.

Both Sir Vincent and Sir Andrew were broadly sympathetic to Puritanism, essentially a continuation of the Protestant creed the Corbets had long upheld during a period of increasing High Church dominance. A legend tells how Sir Vincent was unjustly cursed by Paul Holmyard, a Puritan preacher and one of his tenants, whom he had protected but who was finally arrested by the authorities. Sir Andrew gave a Latin oration at the reburial of Edward Burton of Longner Hall, near Emstrey, to the east of Shrewsbury. Burton had been denied burial in consecrated ground at St Chad's Church, Shrewsbury because of his Protestant beliefs – according to John Foxe, on the very day of Elizabeth I's coronation.[14] He was buried by his friends in his garden and his tomb required restoration by the early 17th century. (It is unclear when the reburial occurred. Augusta Corbet says it was when Andrew was a young man.[15] Barbara Coulton[16] dates it to about 1614, when Corbet was lord lieutenant of the county, although he became deputy lieutenant only in 1624.)

Sir Vincent died in 1623 and was buried at Moreton Corbet on 9 March. Sir Andrew was his recognised heir and was able to take over a fairly consolidated group of estates, with little fear of legal challenge. An inquisition post mortem, held in 1624, listed the Shropshire properties passed on by Sir Vincent to Sir Andrew. Sir Vincent had been

...siezed of the manors of Moreton-Corbet, Shawbury, Besford, and Hatton-on-Hyne-Heath Co. Salop ; and of lands, tenements, etc. in Moreton-Corbet, Preston-Brockhurst, Booley, Edgebaldon, Shawbury, Wythyford Parva, Besford, and Hatton-on-Hyne-Heath, Co. Salop, and three Court leets in Moreton-Corbet, Shawbury, and Besford, the Rectory of Staunton, the tithes in Staunton, Harpcott, Moston, Sowbatche, Heath House, Hatton-on-Hyne-Heath and Greenfields and the advowson of Staunton...He was siezed[sic] in tail male of the Manors of Lawley, Harcott, Hopton and Hopley, Co. Salop, and in divers premises there and in Kenston, Espley, Loxford, Peplow, Whixhill and Shrewsbury and of the advowson of Moreton-Corbet and the tithes in Wythyford Magna and Besford and of the Manors of Acton Reyner and Grynshill and divers premises there, and in Clyve, Astley, Oakhurst, Rowlton, Ellardyne, Charleton Grange, Moston, Pymley, and Berrington and tithes in Oakhurst Co. Salop and died siezed[sic] thereof.

The inquisition also revealed that Sir Vincent had taken the precaution of getting Judith Austin to recognise in writing that the reversion of her jointure properties in Buckinghamshire would be to his descendants. In practice, Sir Andrew was never to enjoy the rents of these lands, as Judith outlived him by three years. Sir Vincent still had considerable debts but he had taken steps to control them. His will explained that he had placed a tract of Shropshire lands centred on Acton Reynald in trust for 41 years so that the rents could be devoted to debt repayments. Sir Andrew was appointed his executor.

Sir Andrew had already been appointed to posts considered appropriate to reliable members of the gentry. He was a justice of the Peace for Shropshire from 1618 until his death.[2] He was commissioner for the subsidy, administering central government taxation, in 1621–22, and again after he succeeded his father in 1624–25 and 1628. With his succession came a series of important posts. In 1624 he was appointed to the Council in Wales and the Marches, which still held decisive power in much of Wales and the border counties of England: the Council had been the main theatre of action of his famous grandfather, the first Sir Andrew Corbet. In the same year, Corbet was appointed Deputy Lieutenant of Shropshire, which at that time meant deputising locally for the President of the Council in the Marches. A major landowner still in Oxfordshire, as well as a trained lawyer, Corbet was made Commissioner of Oyer and Terminer for the county in 1625, a position of great importance in managing the judicial system which he held for the rest of his life.

Parliamentary career

.jpg.webp)

Corbet was returned as Member of Parliament for Shropshire three times: in 1624, 1625 and, after an interlude during the 1626 Parliament, again in 1628. On each occasion he was elected as second in order of precedence to Richard Newport. Shropshire's gentry always returned their own kind to parliament, and always by agreement arrived at before the formal election.[17] There was apparently an informal agreement not to return the same members twice consecutively.

The parliament of 1624–1625

The parliament called in 1624, the fourth of James I's reign, was known as the Happy Parliament because it appeared initially that king and his parliament had at last found a degree of common ground in hostility to Spain. However, it soon fell to the mutual suspicion and hostility that had characterised relations between king and parliament throughout the reign. There were two sessions: the first from 19 February 1624 to 24 May 1624, the other from 2 November 1624 to 16 February 1625. The king died on 27 March 1625 and the parliament was immediately dissolved.

Corbet's contribution to the parliament was not great.[2] He was appointed to two committees, one of them on a bill to regulate heralds' fees. This was a live issue in Shropshire, as the county had received its last heraldic visitation only the year before. The heralds recorded pedigree charts and armorial bearings of gentry and noble families. The fees for registering the pedigrees of gentry families were fairly modest: a Gentleman 25 shillings, an Esquire 35s. a Knight or Baronet 55s. were typical.[18] However, the registration of newly recognised armorial bearings was much more costly – about £20. Shropshire was a gentry dominated county and the number of families wishing to present themselves as gentlefolk was increasing rapidly. Those registered as "of Shrewsbury" had risen from 4 in 1569 to 10 in 1584 and 44 in 1623. The government was invariably insolvent and there was a widespread fear that it was manipulating the honours system to generate funds. Corbet was also sent to a conference with the Lords on a bill to limit legal actions.

Although his contributions were limited, Corbet was enthralled to be at the centre of politics. He wrote to his steward detailing an important debate on war with Spain that took place in February.[2] George Villiers, 1st Duke of Buckingham, who had rashly travelled to Spain incognito with Prince Charles in pursuit of the so-called Spanish Match, gave an account of the venture that clearly impressed Corbet. He commented that "the king of Spain never intended to match with our Prince". He was concerned that Spain was about to launch a surprise attack on England and was shocked by the Spanish ambassador's demand that Buckingham be executed.

The parliament of 1625

The new king, Charles I, summoned a new parliament almost immediately, asking that the same members be returned to it. This accounts for the re-election of Corbet and Newport, in contravention of Shropshire's conventions.[17] The Useless Parliament, so-called because it refused to transact the business demanded by the king, sat only from June to August 1625. Parliament granted the king the taxes of Tonnage and Poundage for only a year, not his lifetime as he had demanded, and a subsidy of £140,000. This impeded the waging of the Anglo-Spanish War.

Corbet's involvement was again not large, although at least two of his responsibilities were important. He was made a member of the privileges committee on 21 June,[2] a crucial body in a time of conflict with the Crown. In August he was sent to a conference with the Lords about pardons for recusants. Despite his Puritan sympathies, Corbet, unlike Newport,[19] had never shown any predilection for denouncing Catholic recusants. The parliament was dissolved later in the month, having refused to grant Charles the financial independence he demanded.

The Forced Loan

Corbet was not returned to parliament again until 1628. He spent much of the interim period involved with the aftermath of the refusal to finance the king's war plans. The war against Spain was poorly-managed and Buckingham's inept handling of relations with France led to a war against two great powers simultaneously. Charles imposed the Forced Loan—a tax levied without parliamentary consent. Corbet was one of the commissioners charged with its collection in Shropshire, under the direction of William Compton, 1st Earl of Northampton, the President of the Council in the Marches.[2] The county gentry had already petitioned the king on unsanctioned taxation, pointing out "how dangerous this course might prove to stir up an insurrection."[17] However, the commissioners met no overt resistance, although payment was at first hesitant. Nothampton promised to use some of the funds to pay off government debts for past military expenditure in the region – so-called "coat and conduct" money. Shropshire paid the Exchequer £2,997 – 82 percent of its quota, compared with the national average of 72%. However, the experience had polarised attitudes, Corbet's included.

The parliament of 1628–1629

Corbet was returned to parliament again in 1628. The parliament assembled on 17 March. On 4 April the House of Commons voted for five subsidies towards the cost of the war. Corbet voted against the fifth and said: "as the case standeth with us, four subsidies is enough".[2] Parliament then moved on to introduce the Petition of Right, specifically forbidding many of the abuses that had taken place in the preceding period. The petition was accepted by the House of Lords but Charles then tried to silence further debate in the Commons, ordering an end to attacks on his ministers. On 5 June members deliberately defied the king, naming Buckingham as the cause of the country's problems. The veteran MP William Strode, a loyal but critical supporter of the government, warned that there was a risk of Parliament being dissolved. Corbet replied: "shall we waive our resolutions for fear of dissolution? Let us go on and God will crown us with happy success." On 11 June Corbet was one of a large group of MPs who resolved to add to a Remonstrance that "the excessive power in the Duke of Buckingham and the abuse of it has been the cause of those evils that have fallen upon us, and is like to be the greatest cause of future dangers."

Corbet's part in parliamentary debate was still modest, but his rapid alienation from the government was an important indicator of polarisation. On 24 April he joined Newport in citing a local official as a recusant. On 7 June he was appointed to the committee responsible for drafting the preamble to the subsidy bill. No speech by Corbet is recorded for the 1629 session of the parliament. However, he was one of those sent to the king with a petition for a national fast.

After the parliament was dissolved on 10 March 1629, the king resolved to rule without parliament and imposed the 11-year period of absolute monarchy known as Thorough. Corbet was never to sit as an MP again, as he died in 1637. His loss of trust in the monarchy was probably duly noted. He was amply qualified by wealth and experience for higher office in his county and beyond, but it was his nephew Robert who was pricked to be High Sheriff of Shropshire in 1635.

Death

Corbet died at the age of about 56 on 6 May 1637 and was buried at Moreton Corbet on 7 May 1637.[9] He died intestate but his wife obtained administration of his goods, valued at £2,200.[2] His eldest son and heir Vincent was still only 19 years of age, but his mother bought his wardship, thus saving the family estates from the depredations of a speculator. An inquisition post mortem was held at Shrewsbury on 19 September and its report gave a competent summary of Corbet property holdings, pointing out that Sir Andrew's mother-in-law, Dame Judith, still had large holdings in Buckinghamshire that were worth nothing to his heir.[20]

Marriage and family

Andrew Corbet married Elizabeth Boothby, a daughter of William Boothby of Delphouse, near Cheadle, Staffordshire by his wife Judith Austin. Elizabeth was the step-daughter of his uncle Richard Corbet (d.1606), who in his later years married (as her third husband) Judith Austin. By Elizabeth he had at least seven sons and nine daughters as follows:[2][15]

- Sir Vincent Corbet, 1st Baronet eldest son and heir, an important royalist commander in Shropshire during the Civil War. In 1642 he was created a baronet "of Moreton Corbet". He married Sarah Monson, a daughter of Sir Robert Monson, a Lincolnshire lawyer and landowner.

- Andrew Corbet

- Walter Corbet, died in infancy

- William Corbet, died in infancy

- Henry Corbet

- Richard Corbet (d.1691), a distinguished royalist soldier in the Civil War, whose mural monument survives in St Bartholomew's Church, Moreton Corbet.

- Arthur Corbet

- Betriche Corbet (or Beatrice) married Francis Thornes of Shelvock Manor, a staunch royalist in the English Civil War. Thornes was Sir Vincent Corbet's trustee and was accused of manipulating the baronet's estate in his own interests.[21]

- Anna Corbet married her cousin, Pelham Corbet, of Leigh and Albright-Hussie.

- Frances Corbet, married Edmund Taylor of Wigmore, Herefordshire, a parliamentarian captain in the Civil War.

- Margaret Corbet, married Thomas Harley of Brampton Bryan Castle and had issue, Sir Robert Harley[22]

- Mary Corbet married John Pearce.

- Alice Corbet married William Onslowe, a Shrewsbury merchant.

- Jane Corbet married a member of the Tibbatt's family.

- Judith Corbet

- Elizabeth Corbet died in infancy

References

- ↑ As seen on Corbet family monuments in Moreton Corbet Church

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 Andrew Thrush and John P. Ferris (editors): History of Parliament Online: Members 1604–1629 – CORBET, Sir Andrew (1580–1637), of Moreton Corbet and Acton Reynell, Salop – Author: Simon Healy. Retrieved 18 September 2013.

- ↑ also known as Francesca

- ↑ John Burke "A General and heraldic dictionary of the peerage and baronetage Volume 1"

- ↑ Coulton, Barbara (2010): Regime and Religion: Shrewsbury 1400–1700, Logaston Press ISBN 978 1 906663 47 6, p. 40

- ↑ P.W. Hasler (editor): History of Parliament Online: Members 1558–1603 – CORBET, Sir Andrew (1522–78) – Author: N. M. Fuidge.

- ↑ P. W. Hasler (editor): History of Parliament Online: Members 1558–1603 – CORBET, Robert (1542–83), of Moreton Corbet, Salop – Author: A. M. Mimardière. Retrieved September 2013.

- ↑ P. W. Hasler (editor): History of Parliament Online: Members 1558–1603 – CORBET, Richard (c1545-1606), of Moreton Corbet, Salop – Author: N. M. Fuidge.

- 1 2 3 Joseph Foster, ed. (1891). "Colericke-Coverley". Alumni Oxonienses 1500–1714. Institute of Historical Research. Retrieved 18 September 2013.

- ↑ Coulton (2010), p. 55.

- ↑ "Kathy Lynn Emerson (2008–13): A Who's Who of Tudor Women: A". Archived from the original on 2 October 2014. Retrieved 18 September 2013.

- ↑ Augusta Elizabeth Brickdale Corbet (1914): The family of Corbet; its life and times, Volume 2, p.305 at Open Library, Internet Archive. Retrieved 12 September 2013.

- ↑ Augusta Elizabeth Brickdale Corbet (1914): The family of Corbet; its life and times, Volume 2, p.308 at Open Library, Internet Archive. Retrieved 12 September 2013.

- ↑ John Foxe: Acts and Monuments (1583 edition), p. 1539 at The Acts and Monuments Online. Retrieved 2 October 2013.

- 1 2 Augusta Elizabeth Brickdale Corbet (1914): The family of Corbet; its life and times, Volume 2, p. 311 at Open Library, Internet Archive. Retrieved 12 September 2013.

- ↑ Coulton, Barbara (2010): Regime and Religion: Shrewsbury 1400–1700, Logaston Press ISBN 978 1 906663 47 6, p. 47 and footnote 15

- 1 2 3 Andrew Thrush and John P. Ferris (editors): History of Parliament Online: Constituencies 1604–1629 – Shropshire – Author: Simon Healy. Retrieved 18 September 2013.

- ↑ George Grazebrook and John Paul Rylands (editors), 1889: The visitation of Shropshire, taken in the year 1623 A-J only by Robert Tresswell, Somerset Herald, and Augustine Vincent, Rouge Croix Pursuivant of arms; marshals and deputies to William Camden, Clarenceux king of arms. With additions from the pedigrees of Shropshire gentry taken by the heralds in the years 1569 and 1584, and other sources. Introduction, Page 21.

- ↑ Andrew Thrush and John P. Ferris (editors): History of Parliament Online: Members 1604–1629 – NEWPORT, Richard (1587–1651), of High Ercall, Salop – Author: Simon Healy. Retrieved 18 September 2013.

- ↑ Augusta Elizabeth Brickdale Corbet (1914): The family of Corbet; its life and times, Volume 2, p.314-316 at Open Library, Internet Archive. Retrieved 12 September 2013.

- ↑ Augusta Elizabeth Brickdale Corbet (1914): The family of Corbet; its life and times, Volume 2, p.341 at Open Library, Internet Archive. Retrieved 12 September 2013.

- ↑ "HARLEY, Sir Robert (1579–1656), of Brampton Bryan, Herefs.; Stanage Lodge, Herefs. and Aldermanbury, London". historyofparliamentonline.org.