Major General Sir Andrew Scott Waugh (3 February 1810 – 21 February 1878) was a British army officer and Surveyor General of India who worked in the Great Trigonometrical Survey. He served under Sir George Everest and succeeded him in 1843. Waugh established a gridiron system of traverses for covering northern India. Waugh is credited with naming the peak of Mount Everest.

Early life

Waugh was the first son of General Gilbert Waugh who served as military auditor-general in Madras. After studying at Edinburgh he joined Addiscombe Military Seminary in 1827 and was commissioned with the Bengal Engineers on 13 December of the same year. He trained at Chatham where he studied under Sir Charles Pasley before reaching India in May 1829. He assisted Captain Hutchinson in establishing a foundry at Kashipur and became an adjutant of the Bengal sappers and miners on 13 April 1831. In 1832 he was posted to the Great Trigonometrical Survey under George Everest. Waugh surveyed many parts of central India before moving to the headquarters in Dehra Dun. Everest noted that Waugh and Renny were the best in mathematical skills and in the handling of instruments.[1]

Surveyor General

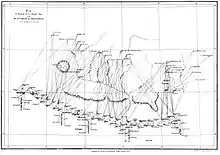

In 1843, Everest retired and recommended that Waugh was the best replacement for the position of Surveyor General. Waugh surveyed the Himalayan region. The survey covered nearly 1690 miles from Sonakoda to Dehra Dun. The great height of this area, however, combined with its unpredictable weather, meant that few useful sightings were obtained before 1847. In an era before the electronic computer, it then took many months for a team of humans to calculate, analyze and extrapolate the trigonometry involved. According to accounts of the time,[2][3][4] it was 1852 when the team's leader of the human computers, Radhanath Sikdar, came to Waugh to announce that what had been labeled as "Peak XV" was the highest point in the region and most likely in the world. Sikdar and Waugh checked their calculations again and again in order to make no mistake in them and then sent a message to Royal Geographical Society from their headquarters in Dehradun, where they found that Kangchenjunga is not the highest peak of the world.[1]

To ensure that there was no error, Waugh took his time and did not publish this result until 1856, when he also proposed that the peak be named Mount Everest in honor of his predecessor. Waugh initially proposed "Mont Everest" but amended it.[5] Everest had always used local names for the features he surveyed, and Waugh had continued the practice. In the case of Peak XV, Waugh argued that with many local names for the mountain, it was impossible for him to identify the name that was most commonly used. Hodgson argued that the native name[6] for it was Deodanga.[7] Another suggestion was that the peak was what Hermann Schlagintweit had identified as Gaurisankar.[8] Though Everest himself objected,[9] the name "Mount Everest" was officially adopted by the Royal Geographical Society several years later.

The height of Mount Everest was calculated to be exactly 29,000 ft (8,839.2 m) high, but was publicly declared to be 29,002 ft (8,839.8 m) in order to avoid the impression that an exact height of 29,000 feet (8,839.2 m) was nothing more than a rounded estimate.[10] Waugh is therefore wittily credited with being "the first person to put two feet on top of Mount Everest".[11]

Waugh noticed errors in the triangulation that appeared to be due to the attraction of the plumbline to the Himalayan mountains and approached the clergyman mathematician Archdeacon John Henry Pratt with the problem. Pratt studied the problem and came up with the idea of isostasy.[12]

Plaudits followed soon after Waugh's identification of Mount Everest. In 1857, the Royal Geographical Society awarded him its Patron's Medal and the following year he was made a Fellow of the Royal Society. Three years later, in 1861, he attained the rank of Major General and was replaced as Surveyor General by Henry Thuillier.[1]

Waugh published a manual of Instructions for Topographical Surveying in 1861 while his survey results were published in numerous reports.[1]

Later life

Waugh died in 1878 and is buried in Brompton Cemetery[1] in west London, midway along the eastern wall.

Personal life

His first wife, Josephine, daughter of Dr. William Graham of Edinburgh, died 22 February 1866, aged 42. His second wife was Cecilia Eliza Adelaide, daughter of Lieutenant-general Thomas Whitehead died on 9 February 1884.[1]

Footnotes

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Vetch, R. H. (revised by Elizabeth Baigent) (2004). "Waugh, Sir Andrew Scott (1810-1878)". Oxford Dictionary of National Biography. Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (online ed.). Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/28900. (Subscription or UK public library membership required.)

- ↑ Ram Gopal Sanyal, ed. (1894). Reminiscences and anecdotes of great men of India: both official and non-official for the last one hundred years. p. 25.

- ↑ See report in 'The Illustrated London News', 15 August 1857

- ↑ Biswas, Soutik (20 October 2003). "The man who 'discovered' Everest". BBC News. Retrieved 9 August 2016.

- ↑ Thuillier, Major (1856). "[Proceedings of the Asiatic Society of Bengal]". Journal of the Asiatic Society of Bengal. 25 (5): 437–439.

- ↑ Hodgson, B.H. (1856). "Native name of Mount Everest". Journal of the Asiatic Society of Bengal. 25: 467–470.

- ↑ Waugh, Andrew Scott (1858). "Mounts Everest and Deodanga". Proceedings of the Royal Geographical Society of London. 2 (2): 102–115. doi:10.2307/1799335. JSTOR 1799335.

- ↑ Walker, J. T. (1886). "A Last Note on Mont Everest". Proceedings of the Royal Geographical Society and Monthly Record of Geography. 8 (4): 257–263. doi:10.2307/1801364. JSTOR 1801364.

- ↑ Notice appended to Waugh 1857.

- ↑ Bellhouse, David (1982). "Letters to the Editor, The problem of numeracy: Mount Everest shrinks". The American Statistician. 36 (1): 64–67. doi:10.1080/00031305.1982.10482782. JSTOR 684102.

- ↑ Beech, Martin (2014). The Pendulum Paradigm: Variations on a Theme and the Measure of Heaven and Earth. Universal-Publishers. p. 267.

- ↑ Subbarayappa, B. V. (1996). "Modern science in India: A legacy of British imperialism?". The European Legacy. 1: 132–136. doi:10.1080/10848779608579384.