Andrew Ure | |

|---|---|

Andrew Ure | |

| Born | 18 May 1778 Glasgow, Scotland |

| Died | 2 January 1857 (aged 78) London, England |

| Nationality | Scottish |

| Spouse | Catherine Monteath 1807 - 1819 (divorced) |

| Scientific career | |

| Fields | Medicine, chemistry, and natural philosophy |

| Institutions | Andersonian Institution, Glasgow |

Andrew Ure FRS (18 May 1778 – 2 January 1857) was a Scottish physician, chemist, scriptural geologist, and early business theorist who founded the Garnet Hill Observatory. He was a fellow of the Royal Astronomical Society and the Royal Society. Ure published a number of books based on his industrial consulting experiences.

Early life, education, and the army

Andrew Ure was born in Glasgow in May 1778, the son of Anne and Alexander Ure, a cheesemonger. In 1801, he received an MD from the University of Glasgow, and served briefly as an army surgeon before re-settling in Glasgow in 1803.[1]

Academic career

Ure became a member of the Faculty of Physicians and Surgeons after his return to Glasgow.[1] He replaced George Birkbeck as professor of natural philosophy (specialising in chemistry and physics) in 1804 at the recently formed Andersonian Institution (now known as University of Strathclyde). His evening lectures in chemistry and mechanics enjoyed considerable success and inspired the foundation of the École des Arts et Métiers in Paris, and a number of mechanical institutions in Britain.[1]

Ure founded the Garnet Hill Observatory in 1808.[2] He and his wife resided in the observatory for several years. The observatory's reputation was second only to Greenwich's at that time. While in residence there, he was assisted by Sir William Herschel, who had come to the area to lecture at the local Astronomical Society. Herschel also took time to help him install a new 14 feet (4.3 m) reflecting telescope (of Ure's design and manufacture). He was elected a Fellow of the Royal Astronomical Society in 1811.[1][lower-alpha 1]

In 1814, while giving guest lectures in Belfast, Ure consulted for the Irish linen board, and devised an 'alkalimeter' which gave volumetric estimates of the alkali contents of industrial substances.[lower-alpha 2] He was also well known in academia at the time for his practical chemistry knowledge and abilities.[1]

On 4 November 1818 Ure assisted the professor of anatomy, James Jeffray,[4] in experiments he had been carrying out on the body of a murderer named Matthew Clydesdale, after the man's execution by hanging.[5][6] Jeffray claimed that, by stimulating the phrenic nerve, life could possibly be restored in cases of suffocation, drowning, or hanging.[6]

Every muscle of the body was immediately agitated with convulsive movements resembling a violent shuddering from cold ... On moving the second rod from hip to heel, the knee being previously bent, the leg was thrown out with such violence as nearly to overturn one of the assistants, who in vain tried to prevent its extension. The body was also made to perform the movements of breathing by stimulating the phrenic nerve and the diaphragm. When the supraorbital nerve was excited 'every muscle in his countenance was simultaneously thrown into fearful action; rage, horror, despair, anguish, and ghastly smiles, united their hideous expressions in the murderer's face, surpassing far the wildest representations of Fuseli or a Kean. At this period several of the spectators were forced to leave the apartment from terror or sickness, and one gentleman fainted.'

— Andrew Ure (1819)[7]

Independent consultant and writer

In 1821 Ure published his first major book, Dictionary of Chemistry, a replacement for William Nicholson's outdated dictionary. It came out two years after William Brande's Manual of Chemistry, and Ure was accused of plagiarism.[8] Subsequently, Ure accused William Henry and Thomas Thomson of plagiarism of his own works.[9]

In 1822, he was elected a Fellow of the Royal Society.[1] By 1830, Ure's outside interests led him to resign first from his chair and then from the institution. He moved to London and set himself up as a consulting chemist (probably the first such in Britain). His work included acting as an expert witness, taking on government commissions, and making industrial tours of England, Belgium, and France. His visits to English textile mills led to his 1835 publication of The Philosophy of Manufactures; followed by An Account of the Cotton Industry in 1836; both dealing with the textile industry conditions. In 1840, he helped found the Pharmaceutical Society of Great Britain.[1]

His exposure to factory conditions led him to consider methods of heating and ventilation for workers, and he is credited with being the first to describe a bi-metallic thermostat.[10]

The Dictionary of Arts, Manufactures and Mines, Ure's chief and most encyclopaedic work, was published in 1837.[lower-alpha 3] Enlarged editions were rapidly called for in 1840, 1843, and 1853. After his death, four further editions appeared—the last in 1878. This work was translated into almost every European language, including Russian and Spanish. The Times review said: "This is a book of vast research, and the variety of subjects embraced in it may be estimated by the fact that on the French translation it was thought advisable to employ nineteen collaborators, all regarded as experts in their special subjects."[11] Historical accounts of the advancement of geology regularly make mention of Ure.[12]

Geology

Ure was a scriptural geologist[13] and in 1829 published A New System of Geology[lower-alpha 4] and was elected an original member of the Geological Society of London .[6] Ure promoted the study of geology, that "...magnificent field of knowledge." However, some criticised the book severely,[1] and "The New System of Geology was not a success, even among readers who might have been expected to be sympathetic, and it was soon forgotten." because "the New System of Geology ... came just too late, at a time when the positions it so noisily defended were being quietly abandoned, leaving the author in slightly ridiculous isolation."[6] Lyell's claimed, falsely, that Ure wanted all promoters of the new geology "...to be burnt at Smithfield." Ure thought both Werner's and Hutton's theories violated every principle of mechanical and chemical science. A sound geological theory, he believed, ought to follow Bacon and Newton's example. And since geology and the Scriptures were the work of God, then they would agree when properly interpreted. Ure said that the Bible was important to the history of the earth. He distinguished between the present functioning of the universe and its origin in the past. For him, the proper science is the repeatable and experimental study of how creation functions in the present. But concerning the unobservable past, we create speculation.[14]

Personal life and death

He married Catherine [née Monteath] Ure in 1807. By 1819 she had become the mistress of an Anderson's Institution colleague, and they divorced.[1]

Ure died in 1857 in London.[1] Throughout his life he had a wide circle of friends and he communicated regularly with many principal scientists around the world. These all lamented his death.[15] Michael Faraday's posthumous description of him was:

…his skill and accuracy were well known as well as the ingenuity of the methods employed in his researches … and it has been stated that no one of his results has ever been impugned. His extensive knowledge enabled him to arrive at conclusions, and to demonstrate facts considered impossible by his compeers in science[16]

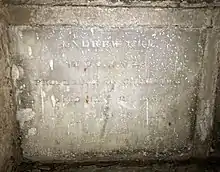

He is buried in the Terrace Catacombs of Highgate Cemetery.[17] A secondary memorial was erected in Glasgow Cathedral by his daughter, Katherine MacKinlay.

Selected works

- A Dictionary of Chemistry[18]

- A New System of Geology[19]

- The Philosophy of Manufactures: or, An Exposition of the Scientific, Moral, and Commercial Economy of the Factory System of Great Britain[20]

- The Cotton Manufacture of Great Britain[21]

- Dictionary of Arts, Manufactures and Mines[22]

- An Account of the Cotton Industry

Notes

- ↑ Herschel's second son, many years later (in 1866), came to occupy Ure's chair in natural philosophy at the Royal Astronomical Society.[1][3]

- ↑ This in turn led him to the concept of normality in volumetric analysis.

- ↑ He received 1,000 guineas (worth about $30,000 in 2010) for Dictionary of Arts, Manufactures and Mines.

- ↑ He received 500 guineas (worth about $15,000 in 2010)[6] for A New System of Geology.

References

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 Cardwell 2004.

- ↑ Wren, Daniel A.; Bedeian, Arthur G. (2008). The Evolution of Management Thought (6th ed.). pp. 70–73.

- ↑ Copeman 1951, p. 658.

- ↑ "james jeffray". ExecutedToday.com.

- ↑ Copeman 1951, pp. 658–59.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Farrar 1973, p. 103.

- ↑ From: Ure, A., (1819), Quart. J. Sci., vol. 6, pp. 283–294. Quoted by Copeman 1951, pp. 658–59, Farrar 1973, p. 103, and in the Oxford Biography (Cardwell 2004).

- ↑ A Manual of Chemistry, on the Basis of Professor Brande's, The North American Review, Vol. 23, No. 53 (Oct 1826)

- ↑ Copeman 1951, pp. 659–60.

- ↑ Ure, Andrew; On the Thermostat or Heat Governor; via Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society of London; 1831

- ↑ Copeman 1951, p. 661.

- ↑ O'Connor 2007, p. 357.

- ↑ Brooke & Cantor 2000, p. 57.

- ↑ BSG 1996, pp. 160-163

- ↑ BSG 1996, pp. 160–61.

- ↑ Copeman 1951, p. 660.

- ↑ Cansick, Frederick Teague (1872). The Monumental Inscriptions of Middlesex Vol 2. J Russell Smith. p. 179. Retrieved 15 October 2021.

- ↑ Ure, Andrew (1821). A Dictionary of Chemistry. London: Thomas & George Underwood; J. Highley & Son; and others. An available edition: Ure, Andrew (1828). Dictionary of Chemistry., 3rd edition (1828).

- ↑ Ure, Andrew (1829). A New System of Geology. London: Longman, Rees, Orme, Brown, & Green.

- ↑ Ure, Andrew (1835). The Philosophy of Manufactures: or, An Exposition of the Scientific, Moral, and Commercial Economy of the Factory System of Great Britain (PDF). London: Charles Knight. Archived from the original (PDF) on 14 February 2012.

- ↑ Ure, Andrew (1836). The Cotton Manufacture of Great Britain. London: Charles Knight.

- ↑ Ure, Andrew (1839). A Dictionary of Arts, Manufactures, and Mines. London: Longman, Orme, Brown, Green and Longmans. An available edition: Ure, Andrew (1870). A Dictionary of Arts, Manufactures, and Mines., a new edition, vol. 1 (1870).

Sources

- Brooke, John Hedley; Cantor, G. N. (2000). Reconstructing nature: the engagement of science and religion. ISBN 0-19-513706-X.

- Cardwell, Donald (2004). "Ure, Andrew (1778–1857)". Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (online ed.). Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/28013. Retrieved 21 July 2012. (Subscription or UK public library membership required.)

- O'Connor, Ralph (2007). "Young-Earth Creationists in Early Nineteenth-century Britain? Towards a reassessment of 'Scriptural Geology'" (PDF). History of Science. Science History Publications Ltd. 45 (150): 357. doi:10.1177/007327530704500401. ISSN 0073-2753. S2CID 146768279.

Accounts of the development of geology routinely make reference to these figures,

- Copeman, W. S. C. (1951). "Andrew Ure, M.D., F.R.S. (1778–1857)". Proceedings of the Royal Society of Medicine. Royal Society of Medicine. 44 (8): 655–662. doi:10.1177/003591575104400804. PMC 2081840. PMID 14864563.

- Mortenson, T.J. (1996). "British scriptural geologists in the first half of the nineteenth century". curve.coventry.ac.uk. Archived from the original on 20 October 2021.

- Farrar, W. V. (February 1973). "Andrew Ure, F.R.S., and the Philosophy of Manufactures". Notes and Records of the Royal Society of London. 27 (2): 299–324. doi:10.1098/rsnr.1973.0021. S2CID 145244662.