Anne de Joyeuse | |

|---|---|

| Baron d'Arques Duc de Joyeuse Admiral of France Governor of Normandie | |

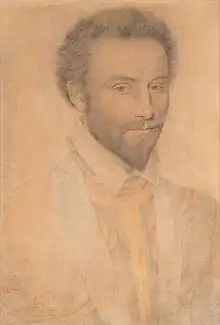

Contemporary portrait of Anne de Joyeuse | |

| Born | c. 1560 |

| Died | 20 October 1587 Coutras |

| Noble family | House of Joyeuse |

| Spouse(s) | Marguerite de Lorraine |

| Father | Guillaume de Joyeuse |

| Mother | Marie de Batarnay |

Anne de Joyeuse, baron d'Arques then duc de Joyeuse (c. 1560–20 October 1587) was a French noble, governor, Admiral, military commander and royal favourite during the reign of Henri III in the French Wars of Religion. The eldest son of Guillaume de Joyeuse and Marie de Batarnay, Joyeuse was part of one of the most prominent noble families in Languedoc. His father served as the lieutenant-general of the province. Joyeuse began his career in the mid 1570s, serving in Languedoc in the fifth civil war before joining the main royal army during the sixth civil war and seeing combat at the Siege of Issoire in late 1577. Around this time he caught the attention of the king and entered into the circle of his favourites, he was made a Gentilhomme de la chambre (gentleman of the chamber) then a Chambellan (chamberlain). By 1579 he would be one of the king's four chief favourites, alongside Épernon, Saint-Luc and D'O. That same year he became governor of the Mont-Saint-Michel. In 1580 civil war resumed and the king dispatched Épernon and Joyeuse to play important roles in the siege of La Fère. Joyeuse would be seriously wounded in the reduction of the city.

Over the next year, D'O and Saint-Luc would each be disgraced in turn, leaving Épernon and Joyeuse as the two poles of the king's favour. Henri elevated them to premier gentilhomme de la chambre, then brought them into the French peerage when he elevated Joyeuse from baron d'Arques to duc de Joyeuse. Around this time he also arranged for a marriage between Joyeuse and the queen's sister Marguerite de Lorraine, a very advantageous match which was celebrated lavishly. Henri desired for his favourites to have control over the military, and therefore bought out the duke of Mayenne from his possession of the Admiralty in mid 1582, with the title going to Joyeuse. Finally in 1583 Joyeuse was made governor of the reconsolidated province of Normandie, the richest province of the kingdom. By this time opposition was growing to the king's two favourites among the upper nobility, among whom some saw Joyeuse as a man taken above his proper station. His appointment in Normandie also caused friction with the Norman nobility. The opposition to Henri and his two favourites was granted new clarity by the death of the king's brother Alençon in July 1584. In the absence of a child, Alençon had been the king's heir, and with a Protestant now heir (the king's distant cousin the king of Navarre) the duke of Guise reformed the Catholic Ligue (League) in opposition to the succession and Henri's favourites.

In March 1585 the ligue entered war with the crown, and Joyeuse was tasked with ensuring that Normandie did not fall to the ligueurs (leaguers). He fought a skirmish with the duke of Guise's cousin the duke of Elbeuf at Beaugency in June of that year in which he came out the better. However the king capitulated to the ligueur demands shortly thereafter, agreeing to exclude Navarre from the succession and make war on Protestantism. In the campaign that followed Joyeuse successfully drove the Protetant prince of Condé from the country in late 1585. By this means Joyeuse began to build his credentials as a (royalist) leader of the Catholic party, in opposition to Guise who sought to lead the Catholic party through the ligue. Épernon meanwhile aligned himself with the Protestant party. At this time, Joyeuse's favour began to deteriorate, as the king increasingly found himself in agreement with Épernon's attempts to seek reconciliation with Navarre. Joyeuse led a royal army into Auvergne in summer 1586 against the Protestants and succeeded in capturing a number of small settlements before his campaign bogged down and he returned to court in failure. He increasingly conducted his campaigns in a brutal fashion and this would climax with the campaign he led in 1587 into Poitou against Navarre in which he massacred several Protestant garrisons. By this means he greatly increased his credit with the preachers of Paris, at the expense of Protestant enmity. Conscious of his declining position at court, he pursued Navarre aggressively, and brought him to battle at Coutras. During the battle that followed he would be killed.

Early life and family

Anne de Joyeuse was born in 1560, the eldest son Guillaume II de Joyeuse and Marie de Batarnay.[1] He was named for his godfather Anne de Montmorency, chief favourite of Henri II.[2] His father had initially been intended for a church career, however with his father dying without other male issue, the royal favourite Montmorency facilitated his extraction from his church career and secured Guillaume an advantageous marriage to his niece. In 1561 he would be established as lieutenant-general of Languedoc, and would serve in this role until his death in 1592.[3] He represented a chief cog in the administration of Henri III's mother Catherine de' Medici during the nominal reign of Charles IX.[4] His mother took an active role in the finances of the family and from November 1588 had power of attorney for the Joyeuse family.[5] Through the Batarnay side of his family, Joyeuse had relatives that had served the kings of France since the reign of Louis XI.[4] Through his mother he was descended from René de Savoie-Tende, bastard son of the duke of Savoie.[6]

Family

The Joyeuse were a noble family from the south of the massif-central. They traced their nobility back to the 12th and 11th Centuries as an offshoot of the house of Châteauneuf-Randon.[3] During the thirteenth century they became barons of Joyeuse from which they would draw their name. In 1431 the barony was erected into a viscounty in favour of Louis de Joyeuse. Several generations later members of the family served as Chambellans (Chamberlains) for the duke of Bourbon and king of France.[7] The Joyeuse family possessed and would continue to develop during the political ascendency of Anne de Joyeuse, a strong clientele system in eastern Languedoc which was of great value to the king in his project to reintegrate the provinces into the royal orbit. Henri III saw their influence in Languedoc as a useful counterbalance to the other main noble family of Languedoc, their former patrons, the Montmorency.[8][9]

Anne had 6 younger brothers, among whom:[3]

- François de Joyeuse (1562-1615), would become a Cardinal.[10]

- Henri de Joyeuse (1563-1608), would become Duke of Joyeuse after Antoine-Scipion.[11]

- Antoine-Scipion de Joyese (1565-1592), would succeed Anne as Duke of Joyeuse.[10]

- Georges de Joyeuse (1567-1584) sieur de Saint-Didier.[12]

- Claude de Joyeuse (1569-1587), baron de Saint-Sauveur would die alongside Anne at the Battle of Coutras.[13]

Marriage

King Henri III began looking for advantageous marriages to cement the position of his chief favourites in court, choosing Marguerite de Lorraine for Joyeuse. There were initially objections to the match from Louise de Lorraine, queen of France and the duke of Lorraine that Joyeuse was of too low a birth to merit such a marriage. Surprisingly Joyeuse's own mother was also unkeen on the match, Marie being greatly fearful that her son would not be able to support the financial costs associated with providing for a princess and thus his ruination would follow.[14] Henri overcame these objections. On 18 September of 1581 Joyeuse was married to Marguerite in a betrothal ceremony at the Louvre.[10][15] The ceremony was witnessed by the cream of the French nobility, among them the duke of Guise and duke of Mercœur representing the brides family and the duke of Montpensier and Cardinal Bourbon for Joyeuse. Also present were the chancellor Birague and garde des sceaux (guard of the seals) Cheverny.[16] The wedding proper took place at the church of Saint-Germain-l'Auxerrois, with the king conducting the bride to the altar on 24 September. Henri dressed in matching clothes with those of Joyeuse, each man wearing a sumptuous costume of pearls and precious stones.[17][18]

After the wedding, festivities known as 'Magnificences' were held for two weeks to celebrate the occasion, with over 50,000 spectators at the various parades. Henri had been planning the details of the events since June.[15] Among the celebrations were tournaments, firework displays, ballets and mock battles in which the king fought the duke of Guise, duke of Montmorency and duke of Mercœur in a variety of allegorical settings.[19] An observer reported that Henri employed a variety of weapons for these combats.[20] To celebrate his marriage, his maternal grandmother, the comtesse du Bouchage gifted Joyeuse a clock.[21] Henri for his part granted Joyeuse a gift of 1,200,000 livres (pounds).[22] This sum was in fact a diversion of the receipts for the year of the city of Caen, half paid immediately to Joyeuse and the other half staggered over the following two years. The marriage contract specified that the sums must be devoted to land purchases.[23] The king also granted him the Château de Limours shortly thereafter, for which the duchess of Bouillon would be compensated 160,000 livres.[24] This Château had in prior years been granted by François I and Henri II to their respective mistresses.[25][26] In the following years, Henri would refer to Joyeuse in letters as mon beau frère (my brother-in-law) a term he had previously only used for Mercœur.[27] Joyeuse's marriage linked him more closely to the monarchy and to the Lorraine family in opposition to the other chief royal favourite Épernon. The match brought great benefits to Mercœur, as Marguerite surrendered her rights of succession to any Lorraine inheritance to him upon the marriage.[28] Marguerite was a cousin of the duke of Guise the leader of the Catholic ligue (League)[29]

The amount spent on the wedding astonished and flabbergasted contemporaries. The diarist Pierre de l'Estoile wrote of the 'enormity and waste' at a time when there was much need in France.[30] During the period in which the wedding took place, there were disorders in Guyenne, Languedoc and Dauphiné, many of which stemmed from a lack of funds.[31] At the time of the wedding, the king's brother Alençon was campaigning in Nederland. His troops were woefully underfunded due to the inability of the Dutch States to provide him the money they promised, and he bitterly protested to Henri for spending so lavishly on a wedding instead of providing more money to support him.[32] The wedding was not without its supporters however, the acclaimed poet Pierre de Ronsard opined approvingly of the match. He would composed an Epithalamium for the occasion, celebrating the virtues of Joyeuse.[33][34]

As a married man, Joyeuse would participate in many brief infidelities, for which he sought ritual purification from time to time.[35] Despite this he expressed great longing when separated from his wife in his letters, calling for Marguerite to come join him at Niort as he prepared to conduct the siege of Fontenay which he feared might take a significant time to reduce. He also excitedly wrote when he suspected she might be pregnant.[21] His grandmother, the comtesse du Bouchage would develop a strong rapport of correspondence with Marguerite, and Marguerite would regularly write to her when Joyeuse was unable to.[21]

Education

Arques (as Joyeuse was known prior to September 1581) had an extensive education, first under the tutelage of Master Martin in his home region at Toulouse. It was reported that this education had a good effect on Arques, developing him into a 'valiant and well-mannered gentleman'. He was able to produce good letters. In 1573 he and his brother Henri finished their educations at the Collège de Navarre in Paris, a prestigious institution which was attended by many of the leading nobles of France such as Admiral Coligny and the duke of Aumale.[36][3] His father considered withdrawing him to a provincial university in response to the plague that racked the capital in that year but ultimately let him finish his education there.[2] This education had the result of producing a man considered cultured by the standards of his day, who enjoyed the company of 'men of letters'.[33] In 1583 he became the patron of a group of Italian actors, who would dedicate a play to him. In 1585 Pierre de Dampmartin dedicated a treatise to Arques, holding him up as a cultured example to the French nobility.[37] Alongside Marshal Retz he would be the chief financier among the courtiers of the king of the Académie which attracted the praise of the poet Baïf.[38] The poet Philippe Desportes would become a key member of his fidelity network in Paris, acting as an intermediary with leading Parlementaires (members of the Paris court) such as Jacques Auguste de Thou and recommended the idea of Arques' marriage to the king. As a reward for his services Arques attempted to secure the bishopric of Senlis for the poet, but the king rebuffed the idea.[39] Arques would also patronise the visual arts, receiving a miniature portrait from the famous English artist Nicholas Hilliard in the Livre d'heures de la reine Louise (Book of hours of queen Louise).[40] Alongside his intellectual interests, Arques was an avid dancer, writing to his grandmother on the occasion of his aunt's marriage to assure her that he would dance as well as he knew how for the wedding festivities. In February 1586 he, Épernon and the king trained for a ballet.[41]

Residence

When residing in Paris in his youth, Joyeuse and his brothers were able to stay at a hôtel (a city residence for wealthy or noble men) owned by his maternal family, the Bouchage on the rue du Coq. After entering royal favour, Joyeuse desired his own hôtel and rented one known as the Cygne blanc on the rue Saint-Honoré from a merchant for the expensive sum of 1200 livres a month from 1580. The king did not feel such accommodation was sufficient for a favourite of Joyeuse's standing, and purchased for him the hôtel de La Marck in June 1582 for 45,000 livres. This residence was conveniently close to the Louvre, only two streets away and allowed him to begin hosting his own fidelity network in Paris.[42] Joyeuse would not need to rely on this residence alone for his proximity to the Louvre, as alongside Épernon he would enjoy lodgings inside the Louvre itself after becoming premier gentilhomme de la chambre (First Gentleman of the Chamber).[43]

Health

Joyeuse would lead a sickly life, regularly beguiled by Tertian Fever. This would particularly beguile him during 1583 to the point he was unable to travel to Normandie for the holding of the provincial Estates. Alongside Tertian fever he was also subject to Sciatica for which the king's doctor Miron advised a treatment program of bathing. Alongside these health problems, he also suffered a kick from a horse in April 1585 and had his jaw shattered by an arquebus at the siege of La Fère in 1580. The various health problems that afflicted him often formed the subject of the letters he wrote to his most frequent correspondent, his maternal grandmother the comtesse du Bouchage.[44]

Reputation

Among the enemies of the royal favourites, both ligueur and Protestant Joyeuse and the other favourites of the king would be attacked as 'effeminate' and 'homosexual'. During the campaign of 1587 the Protestant king of Navarre responded to a representative of Joyeuse that Henri III and his courtiers 'were too perfumed and delicate to approach a man like him, whose only perfume was gunpowder'.[45]

Rise

First service

In the earliest stages of his career, Arques served in the retinue of Damville, brother to the duke of Montmorency and governor of Languedoc. This was logical for him as the Montmorency family had served as protectors of the Joyeuse for many years.[2] Arques made his military debut in the year 1575 during the Fifth French War of Religion. During this war his service was close to home, in Languedoc.[3] This first military service was under the command of his father against the Protestant forces of the vicomte de Turenne, the elder Joyeuse being in command of an ordinance company.[2][46]

By 1577 he was at the head of a company of men-at-arms in the province for the combats of the Sixth War. At first he served again in Languedoc, seeing combat at Carcassonne.[2] By this time however he was ready to move beyond the boundaries of Languedoc, and joined the main royal army of the war which was under the nominal command of king Henri III's brother Alençon. As a result he was with Alençon for the siege of Issoire. Some time between the capture of the city and the Peace of Bergerac which brought the civil war to a close he was introduced to the royal court and quickly entered the circle of favourites around Henri III.[10] Le Roux speculates the king may have been drawn to him for two possible reasons, firstly to gain the fidelity of a powerful Languedoc house which he could employ against the Montmorency, second to deny his brother Alençon a potential favourite.[2] He would be among the youngest of the men that surrounded Henri, the same age as the favourites Louis de Maugiron and Georges de Schomberg.[1] By the end of 1577 he is recorded in the memoires of Jules Gassot as a favourite of the king.[47] He served Henri first in his household as a gentilhomme de la chambre (Gentleman of the Chamber) in 1577, before receiving the more prestigious post of Chambellan (Chamberlain) in 1579 which he would hold until 1582.[48][49]

Entering the circle of royal favourites, which was composed of men such as René de Villequier, Caylus, Gaspard de Schomberg and Saint-Mégrin, Arques found himself involved in the competition with the favourites of Alençon under whom he had fought in the civil war which had brought him to the king's attention. Duels and other acts of violence were common between the competing favourites. [50] On 1 February, Arques participated in a showdown with the seigneur de Bussy, chief favourite of Alençon alongside many other favourites of the king at the porte Saint-Honoré in Paris. Bussy would escape the ambush they had laid.[51] In the wake of the attack, Alençon resolved to leave court though he would not do so until 14 February.[52] He was among those who spent the evenings in conversation with the king after the flight of Alençon from court in February. Henri was not initially concerned by the absence of his brother, however the favourites reminded him of the consequences of Alençon's last flight from court in 1575, when he had put himself at the head of the king's opponents and forced a humiliating peace upon the crown.[53] Alongside many other of Henri's favourites, Arques would depart temporarily later in February 1580, with Henri hoping that by dismissing his favourites he could coax his brother Alençon to return to court. Henri also feared, that if young men like Arques remained in the capital, they would be killed by Alençon's favourites. Arques duly left the capital and returned to his home province.[54][55]

As a result of the violence of the court, many of the favourites of the king would be dead by the end of 1578.[56] Indeed, it was the violent Duel of the Mignons in which Caylus and Maugiron were killed, that helped facilitate the ascent of the two new men (Arques and Épernon) in the king's attentions.[57]

Four evangelists

Arques quickly rose in royal favour. This is observed in the ceremony conducted on 1 January 1579 at the church of the Grands-Augustins in which the king established his new order of chivalry the Ordre du Saint-Esprit (Order of the Holy Spirit) to replace the 'diluted and debased' Ordre de Saint-Michel (Order of Saint Michael) as the most senior order of French chivalry.[58] Arques stood behind the king alongside Épernon, D'O and Saint-Luc as he received the first intake of chevaliers (knights), the four dressed in identical outfits that matched the kings. The other courtiers were separated by a greater distance from the king, and it was understood that in the choice of outfits the king was declaring that the four men were his ascendent favourites.[18][59] Contemporaries nicknamed them the 'four evangelists'.[60]

With disorders consuming the south of France, the king's mother Catherine de Medici was dispatched to travel south and do what she could to resolve matters. Arques was dispatched south in March 1579, while Catherine was negotiating peace in Gascogne to inform her that the king's brother Alençon had returned to court.[61] While in the south, Arques acted as an intermediary between Catherine and Henri, writing to Henri in April 1579 to appraise the king of the situation in the Midi and the state of marriage negotiations as concerned the king's brother Alençon. Catherine was effusive in her praise for Arques, telling Henri of his zeal, and encouraging him to raise his own men to positions of authority to supplant those whose loyalty was more questionable.[62]

First commands

In that year, Arques was established as governor of the famous fortified island of Mont-Saint-Michel.[63] He acquired this post in survivance of his maternal grandfather René de Batarnay who had held the charge previously.[49]

In February 1579, he became captain of a company of 50 lances which by 1581 had been expanded to 100. This company had previously been under the authority of Jacques d'Humières, founder of the first Catholic Ligue (League) and governor of Péronne who had recently died. Therefore it was composed of zealous Picard Catholics. [10] The extent of his practical authority over the men of his company was limited. In 1585, Adrien d'Humières who was in theory his lieutenant, joined the second Catholic ligue.[64] The company ensign Hugues de Forceville would prove equally disloyal, joining the ligue in 1589. By 1582, Arques had succeeded in largely reshaping the force, utilising the expansion from 50 to 100 lances to bring his own fidelity network from Normandie to bear on the company. In the years since gaining authority over the company, it would mainly be employed by Arques to combat the military efforts of the king's brother Alençon to raise French troops for Nederland, with one of the archers of the company being killed by Alençon's supporter the sieur de Fervaques in 1581.[65] By the mid 1580s, the purpose of the company would change, and it would be brought closer to Paris where it could function more protectively for the court.[66]

This bestowal of military responsibilities was part of a stratagem that Henri had begun to employ in the years prior with the provision of commands to D'O, Saint-Luc and Saint-Mégrin. By this means, Henri hoped to assert his personal control over the military.[67]

During 1579, a vacancy opened in the Marshalate. According to the contemporary historian de Thou it was Arques who successfully campaigned for D'Aumont to fill the post.[64]

At some point in the first half of 1580, Arques received the honour of induction into the Ordre de Saint-Michel (Order of Saint Michael). While no longer the most prestigious order of French chivalry since the creation of Saint-Esprit, this remained a significant honour for the young man.[14]

By this time, Arques had been elevated in the king's favour to the point where he was invited on the king's semi regular retreats from court. In February 1580 alongside La Valette, Joachim de Châteauvieux and François d'O he joined the king on an excursion to Saint-Germain. After the siege of La Fère, Arques, D'O and Épernon were invited to Ollainville by the king.[68] He would regularly join the king on these excursions in the coming years, at which the groups would attend balls and other festivities. After these periods, the king would return to court refreshed and ready to tackle matters of state.[69] To better participate in the king's departures from court, Arques and his brother Henri de Joyeuse, comte du Bouchage purchased apartments at Ollainville.[70] Alongside joining the king on his excursions, Joyeuse would also be the subject of royal visits, as when in May 1581 he was ill, residing at his grandparents château in Montrésor. Henri, alongside D'O and Épernon left court to visit him there.[71]

La Fère

Civil war again erupted in 1580 when the prince of Condé seized the city of La Fère. A royal army was sent to secure its recapture. The royal effort to reduce the city was led by Marshal Matignon. Under his command were many royal favourites including Arques and Épernon. The two royal favourites departed court for the siege lines on 1 July, having been granted 20,000 couronnes (crowns) by the king as well as cloth and silver for their entourages. Contemporaries denounced the sum that the king had granted them prior to their departure, describing them as living in luxury on the siege lines. Matignon began the assaults on the city on 7 July. For the conduct of the siege Arques commanded his 50 lances, while Épernon commanded the Champagne regiment. Alongside Arques was his sibling Bouchage.[72] Both Arques and Épernon set about creating an orbit of nobles around them upon their arrival, redistributing the sum they had received from the king to create networks of loyalty.[73] During an assault on the city conducted on 18 July, Épernon was wounded and Arques received an arquebus shot to the face. The shot was serious and deprived him of seven teeth and part of his jaw. He was taken to the Château de Mouy where he underwent his recovery, writing to his grandmother on 26 July that he was in both extreme pain and filled with anger. By early August he wrote that his condition was more an annoyance than a pain any more, and only his difficulty with eating troubled him. By 9 August he was ready to return to the front lines[74] On 12 September La Fère capitulated, with Épernon demanding the governate of the city, which he received much to the annoyance of Matignon.[10][75][76][77][78][79]

Arques' return to court in the wake of the siege would be a triumphant one, however the narrative of the siege would be different among the bourgeois of Paris who viewed his activities at La Fère with displeasure.[74]

Ascendency

During 1581 Henri decided to establish a secret inner council, where the real business of state could be conducted, away from grandees such as the duke of Guise. This new council was greatly associated with the two men becoming his chief favourites, Arques and Épernon both of whom functioned as 'principle ministers of the new cabinet'.[22] As a part of the important position Henri had provided the men with, he expected them in return to act as intermediaries with the provincial nobility and form their own fidelity networks that would be loyal to the crown through the distribution of honours. This would have the side benefit of saving the crown money, which was always in short supply.[80]

Fidelity network

To this end Arques secured the elevation of Aymar de Chaste and Jacques de Budos to gentilhomme de la chambre (gentleman of the chamber). Budos was a baron from Languedoc and distant relative of Arques. At Arques' request he would become a vicomte in 1583.[81] At his request the governor of Narbonne the baron de Rieux became a chevalier de l'Ordre du Saint-Esprit (knight of the order of the Holy Spirit) in 1585. Rieux was a key ally of the Joyeuse family in Languedoc.[82] He would follow this by securing two further appointments to the order in 1586 for lieutenant-generals of Normandie: the seigneur de Pierrecourt and Carrouges.[83] In a conversation with the Savoyard ambassador Lucinge in 1585, Arques boasted that even the lowest man in the network he had built would bring 400 gentleman in support of him if required.[84] He targeted also nobles that appeared to be at risk of defecting to the Catholic ligue, such as Manou and La Châtre.[85] This policy had great success for the king, the duke of Guise finding himself able to count on almost no figures in the court by 1586, forcing him to look elsewhere to secure his power. Looking at the networks in totality, Arques' would be relatively geographically diverse, while Épernon's was more concentrated among the nobility of the south west.[86]

In total Henri envisaged that the two men would assist in the reintegration of principal provinces whose connections to the crown had been damaged by the years of civil war. They would also be guides for the nobility, steering the institution away from the Lorraine Catholic party, the Protestants and the party of the king's brother Alençon.[87]

Disgrace of the evangelists

Favour had previously been more distributed, however in the preceding months both François d'O and Saint-Luc had been disgraced, leaving only Arques and Épernon at the centre of the king's attentions.[88] Saint-Luc had been growing in discontent in his relationship with the king for some time, and a dispute with Arques furthered the distance between them. Saint-Luc desired greatly for himself the great office of grand écuyer (Grand Squire) which was currently possessed by the comte de Chabot-Charny, and he was furious to find out that Arques had seduced the counts daughter and Chabot-Charny was speaking of providing the office and his daughter to Arques. The office had been promised to Saint-Luc on the occasion of his marriage by the king, however Chabot-Charny was uninterested in honouring this arrangement. Saint-Luc complained to the king who retorted that he had granted many privileges to Saint-Luc for which he should be grateful.[89] Saint-Luc angrily rejoindered that there was little worth in raising men to the esteem of princes if the king was only going to cast them back down.[90]

When the final break came with the king, there would be many stories as to what had finally severed relations between Saint-Luc and the king. In one of them, Saint-Luc and Arques attempted to scare the king with a brass pipe in which they imitated the voice of an angel upbraiding the king for his sins. The prank accomplished, Arques denounced Saint-Luc as the author of the enterprise to the king. However given the multiplicity of stories as to the cause of Saint-Luc's final dismissal, it is questionable how seriously this story can be taken. This is especially true when one considers a letter written by Arques to his grandmother in which he defends Saint-Luc, making it more likely that D'O was the instigator of his downfall.[91] Moreover, even after Saint-Luc's disgrace, Arques wrote friendly letters to the former favourite.[90] Saint-Luc would respond favourably from his exile at Brouage, and in the years that followed Arques would become the ex-favourites protector at court.[92]

D'O was greatly embittered by the rise of Arques and Épernon which threatened his place in the court. The men had grown to hate each other over their holiday's together from the court at Ollainville.[93] He particularly resented Arques for having secured a marriage to the sister of the king in 1581.[94] In the hopes of regaining his position, he attempted to sow discord between Arques and Épernon. When this was uncovered, the king dismissed him at the urgings of Épernon.[37][95] The disgrace of D'O brought further benefit to the Joyeuse family, with Arques' brother Bouchage receiving the office of maître de la garde-robe (Master of the Wardrobe).[96]

Intermarriage

Henri hoped to avoid rivalries between his two paramount favourites, and to this end arranged marriages between the families. Bouchage, Arques' brother was married Catherine de Nogaret in November 1581, and several months later La Valette, Épernons elder brother married Anne de Batarnay, Arques' maternal aunt.[97] Arques was a witness to the signing of Bouchage's marriage contract in November. Arques' mother Marie was very hostile to the match of their family with Catherine.[98] The marriage between La Valette and Anne would be a great success despite Catherine being much older.[99] La Valette would serve as an intermediary between Arques and Épernon in the coming years.[100] The bonds between the two families would deteriorate with the death of first Catherine in 1587, then Anne in 1591 and La Valette in 1592. However they would not collapse entirely thanks to the efforts of Épernon.[101]

As a result of the central attentions bestowed upon the two men, they became despised to varying degrees by segments of the high nobility and population of France. The heights to which each would be elevated disgusted supporters of the Lorraine and Montmorency family who saw their own centrality in French politics as natural. To this end a bitter war of pamphlets and preaching would be conducted against them from 1578 to the king's death in 1589.[102]

The king wrote to Arques's grandmother, the comtesse du Bouchage during this year, explaining that there was no difference for him in the affection he showed Arques from that he would grant his son. In 1581 Henri would write on this theme, saying it was his responsibility as a housekeeper to ensure that his three sons (Arques, Épernon and D'O - prior to the latter's disgrace) were all married off.[68] Some historians have interpreted the effusive affection that Henri showed in his letters to Arques himself as a form of erotic desire.[103] Henri was not however without caution concerning the rapid honours he bestowed upon his chief favourites, and at one point at least developed concerns that Arques might develop into an overmighty subject.[104]

Duc de Joyeuse

Henri was determined that his principal favourites have an aristocratic standing to match the esteem with which he was now placing them in. To this end, the viscounty of Joyeuse was raised to duché pairie (Peerage Duchy) in Arques' favour in August 1581 (making the baron d'Arques the duc de Joyeuse). The letters-patent confirming this were registered by the Parlement on 7 September. In them the king expounded upon how the raising was in return for the 'painful labours' the Joyeuse family had undergone in service of the crown. The families 'service against the Saracens' and other 'enemies of France', alongside the ancient dignity of their house was also cited.[105][106] In November of that year Épernon would in turn be raised to the position of duke.[22][107] Joyeuse was among the peers who accompanied Épernon to the Paris Parlement for the registration of the letters patent that confirmed this.[108] Arques was granted a vaunted placement in the peerage he had just entered, receiving precedence over all other ducal peers with the exception of those of sovereign houses, the duke of Guise (Lorraine), the duke of Nemours (Savoie) and the duke of Nevers (Mantova).[33] Épernon would receive similar precedence.[109] Henri reasoned that Joyeuse took this place of precedence due to his recent marriage to the sister of the queen Marguerite de Lorraine.[110] Due to this, Joyeuse took precedence in the hierarchy of peers over Épernon, who was for the moment unmarried, though the king hoped to pair him with Christine de Lorraine.[111] Joyeuse and Épernon represented a new generation of favourites for Henri, ones who had more capacity and interest for matters of state governance than those who had initially risen with Henri upon his ascent to the crown.[112]

The new 'duchy of Joyeuse' was an agglomeration of the former viscounty which had been possessed by Joyeuse's father, alongside Baubiac, Rosieres, La Blachier, La Baume, Saint-Auban, Saint-André, Cougeres, Saint-Sauveur, Bec-de-Jon, Latte, Duniere, the barony of Saint-Didier and the barony of La Mastre.[106] In total this expanded domain of Joyeuse would bring him revenues of around 10,000 livres.[23]

The raising of his two chief favourites to the French peerage came amid a flurry of ducal erections by the king. In September the marquisate d'Elbeuf was raised to a duché pairie, followed by the duc de Piney-Luxembourg in October and the comte de Retz in November.[113]

Premier gentilhomme

On 31 December of that year, Henri established Épernon and Joyeuse as co-holders of the office of premier gentilhomme de la chambre du roi. Joyeuse was established to the office through the dispossession of Marshal Retz who had held the honour previously. Retz' coholder Villequier refused to be bought out of the office, and therefore was maintained as a third premier gentilhomme until 1589, though without the honours accorded the other two.[114] They were to alternate who held the title throughout the year.[22] In theory this meant that Joyeuse was the premier gentilhomme from January to April, Épernon from May to August and Villequier from September to December.[115] This meant that his two favourites now controlled who could enter and leave the royal residence and therefore access to the king. They also had the exclusive right to be near the king in the time between his waking and dressing for the day, including the honour of passing him his clothes.[116] Beyond this Joyeuse and Épernon had exclusive access to the king's personal cabinet, including the right to enter it even when the king was absent, Villequier did not have this right.[117] Other favourites of the king would have to wait in an antechamber before being granted access to the king.[118] On Sundays when the king ate without ceremony with various courtiers, a place of honour at the bas bout (Bottom end) of the table was always reserved for one of the two men.[119]

The two men were expected by the king to act as a screen concerning access to him, with petitioners interested in Henri's attention to address their concerns to one of the two men who would then if they felt it appropriate present the matter to Henri. By this means, Henri distanced himself from petitioners and delegates the responsibility of determining what business merited his time. Therefore for example, when Joyeuse received a request from madame de La Trémoille he withheld it as he did not believe Henri to be in the mood for business matters presently.[104] As part of their elevation, both men resigned the office of Chambellan, that they had previously held to their brothers La Valette and Bouchage.[120] The traditional wage of a premier gentilhomme was 1200 livres, however in 1585 this was expanded to 3500 livres.[115]

By their elevation to the office of premier gentilhomme they formed part of a strategy by the king to dilute the authority the duke of Guise held over the crown from his office of grand maître (Grand Master). Both men would also be encouraged to form their own patronage networks, in the hopes of cutting down royal expenditure.[121] Also involved in this effort to limit the grand maître was the creation of Richelieu as grand prévôt (Grand Provost) and Rhodes as grand maître des cérémonies (Grand Master of Ceremonies). Each of these offices was allowed to chip into the authority of grand maître.[122]

Many princes took offence to the spatial domination of the court that the two favourites secured by this appointment. To this end they ceased to attend the Louvre.[123]

For a time after his marriage, Joyeuse engaged in a rapprochement with the house of Lorraine. Thus in the weeks that followed Joyeuse could be found alongside Guise with the king on trips around the Île de France. He also took to riding alongside the duke of Guise. However this friendship would quickly give way to competition as each man sought to establish themselves at the head of the Catholic party. To this end he established himself as an intermediary with the Papal Nuncio for choices of who received various benefices. In late 1584 he escalated his displays of contempt for Guise as it became clear that the duke had rebellious intentions with the re-founded Catholic ligue.[124]

Joyeuse took advantage of the gifts he had received during 1581 to invest in land as was expected of him by his marriage contract. To this end he purchased the barony of La Faulche in Champagne in December.[26] He was further able to persuade the king to elevate his father, the lieutenant-general of Languedoc to the Marshalate upon the death of the incumbent Marshal Cossé on 20 January 1582.[125]

On the same day that they received the honour of being made premier gentilhomme, both Joyeuse and Épernon were inducted into the Ordre du Saint-Esprit that they had borne witness to the creation of back in 1579. Henri hoped that the men's presence in the highest order of chivalry would help quiet the derisory nickname of 'arch-mignon' that now accompanied the two men.[126]

Languedoc

Both Joyeuse and Épernon were the sons of important men in their respective provinces of Languedoc and Guyenne, the lieutenant-generals of each province. The Joyeuse family was however more established than the Nogarets, with historic ties to the Montmorency clan, which gave Joyeuse an edge in social respectability.[127] The Joyeuse military control over Languedoc was however limited, as Guillaume de Joyeuse had to contend with the power of the Protestant dominated Nîmes and the duke of Bouillon, as well as the governor proper.[128] Joyeuse worked to increase his families position in Languedoc, and to this end secured the Archbishopric of Narbonne for his brother François in 1581, following this up with the establishment of Antoine-Scipion as grand prieur de l'Ordre de Malte (Grand Prior of the Order of Malta) for Toulouse in 1582. Later in 1584, François would become archbishop of Toulouse.[129] As his star rose tensions escalated with his families former patrons the Montmorency. This exploded into the open at the Estates of Bézieres in October 1581 when the Estates sent out a large delegation to meet the new duke, much to Montmorency's annoyance.[130]

Several attempts at reconciliations between the two families would be undertaken in 1583 though none would bear fruit, with proposals included the exchange of Montmorency's children as hostage. Joyeuse's father therefore took radical steps including seizing Narbonne and attempting to take Bézieres. Joyeuse himself took the opportunity at court to pressure the king of the necessity of relieving Montmorency of his control of Languedoc to de-escalate the situation.[130]

Montmorency was to be offered the governate of the Île de France in exchange, however Montmorency recognised that the large independence he enjoyed as a governor in the south would not be replicable in such a post and declined.[13] Joyeuse himself met with Montmorency at Nissan-lez-Enserune that year in pursuit of that strategy, however Montmorency remained uninterested.[131] Beyond his general rivalry with the Joyeuse in Languedoc Montmorency had particular distaste for Anne de Joyeuse, seeing in him the obstacle to any possibility of ever returning from his southern stronghold to court life.[130]

Admiral de France

At this time, the duke of Mayenne, brother of the duke of Guise, was the Admiral of France. Henri was however determined that the military should be under royal control. As such negotiations began for Mayenne to resign the charge of Admiral to Joyeuse. A title of the importance of Admiral would require significant compensation be granted to Mayenne for relinquishing it, and it was agreed that he would be awarded 360,000 livres and receive the elevation of his cousin Elbeuf's marquisate into a duchy.[22] Unlike the charge of Marshal, it was not supposed that a man made Admiral would have any specific naval experience and the post had a history of being granted to royal favourites going back to the start of the century.[132] Counter-intuitively it was through his authority as Admiral that Joyeuse would be able to command land armies, which he had previously had no authority to do.[133] Having appointed Joyeuse to the post in May 1582, on 1 June 1582 Mayenne resigned the charge of Admiral to him.[134] This would be confirmed in Joyeuse taking an oath in front of Parlement on 19 June.[132] One of the perks Joyeuse took advantage of in his new office of Admiral was to take a cut of the profits of all fish sales in Paris. This brought him an income of 28,000 livres a year.[135]

Whenever the English ambassador wished to discuss matters related to naval affairs with the French court going forward, it was to Joyeuse that he would address himself. Henri ensured Joyeuse was always present when the English ambassador was received. In 1583 after the French Fury (failed seizure of Antwerp by Alençon) resulted in the massacre of the French soldiers in Antwerp, Henri ordered that Joyeuse use his authority to retaliate against the Flemings by impounding all their ships which were presently in the ports of Bretagne.[133]

In March 1584, the specific parameters of Joyeuse's naval responsibilities were outlined in an edict. He was to have authority over the fleets, all ports and naval fortifications and justice on the sea. The edict went further, breaking down even who was to receive any treasures recovered from shipwrecks.[136] The wide reach of the responsibilities encompassed in this edict aroused the fury of Joyeuse's brother in law the duke of Mercœur, governor of Bretagne. He valued the naval control he possessed in his province and was little inclined to give it to Joyeuse.[137] The dispute between the two grandees was settled by Joyeuse's wife Marguerite who convinced Joyeuse to allow Mercœur to hold onto naval responsibilities in his governate.[138]

During the Portuguese succession crisis that began in 1580, France intervened in search of advantage. An expedition was undertaken under the command of Strozzi that looked to gain many of the islands under Portuguese control. The expedition was a disaster with Strozzi's force being destroyed by a Spanish fleet under the marqués de Santa Cruz. His summary executions of many nobles aroused the fury of the French court, Catherine de Medici vowing to send a new expedition to avenge the prior, with the duke of Brissac at its head. Henri however intervened, after the disaster of the first expedition, the matter of the naval expedition should be left to the Admiral of France, Joyeuse. While Joyeuse himself was initially floated to both requisition the boats required and lead the expedition, the king was unable to tolerate his absence, and therefore it was for Joyeuse to nominate another commander.[139] Joyeuse selected his cousin Aymar de Chaste a commander of the Order of Malta to lead the expedition to the Açores.[140][141] As for the acquisition of the boats, Joyeuse delegated this responsibility to Catherine, who was able to negotiate their acquisition from the Hanseatic ports and Scandinavians.[142] The expedition would however prove as disastrous as the first, Chastes' forces outnumbered on their arrival coming to terms with Santa Cruz in return for being allowed to return home to France.[143]

In his capacity as Admiral, Joyeuse sought to oppose the designs of the duke of Guise and various allied lords for an invasion of England to liberate Mary, Queen of Scots. Elizabeth had protested to Henri of the ships being prepared at channel ports, and Henri entrusted responsibility for frustrating the expedition to him. To facilitate this further, Joyeuse was specifically made Admiral of Normandie.[144] Joyeuse set about installing various men loyal to him in command of the channel ports. Soon logistical problems overcame the expedition and the duke of Guise withdrew his backing.[145]

Spiritual affairs

The king was by this point in his reign, desperate for an heir that would secure the royal line, having been unable to produce one. On 11 August 1582 he undertook a pilgrimage to the Notre-Dame du Puy in Auvergne, in the hopes that god would grand him his wish. Accompanying him on this important trip were Jesuits, Épernon and Joyeuse.[146]

Henri decided, in March of 1583 to establish a penitential confraternity. A demonstration of his piety he was keen to invite his courtiers, magistrates of the Parlement and Chambres des Comptes (Chamber of Accounts) to participate. Joyeuse and Épernon both joined the new order, however among some segments of the population the "Mediterranean" religiosity of the court grated against Parisian sensibilities.[147][148] The Joyeuse family would build on this penitential movement themselves in August, when François de Joyeuse established the Pénitents bleus de Saint-Jérôme (Blue penitents of Saint Jerome). The confraternity would have 72 members, largely composed of court favourites (Retz, Villequier, Châteauvieux etc.) and their families, among them of course his brothers including Joyeuse.[149]

The Joyeuse family were the most aligned to the king in his spiritual life, sharing his enthusiasm for penitential pursuits. Indeed one of Joyeuse's brothers would die of a chill contracted walking barefoot in a penitential procession. The two men said their matins together and prayed with one another to have children. Joyeuse accompanied the king on his monastic retreats, which became more frequent in the 1580s.[150]

Normandie

On 28 March 1583 Joyeuse succeeded to the post of governor of Normandie, the richest province in the kingdom.[137] In total Normandie was responsible for between 1/4 and 1/3 of all royal revenues.[134] This office had traditionally been given to the dauphin of France.[13] By his ascent he replaced the three prior governors of the province, Marshal Matignon, Meilleraye and Carrouges among whom the province had been split since 1574.[151] At the same time, the disgraced D'O was bought out of his position as commander of the Château of Caen in Normandie in favour of Joyeuse.[95] To compensate the three men for their dispossession each was given 6000 livres and returned to the positions they had held prior to their ascent to governors, lieutenant-generals of Rouen, Evreux, Caen, Caux and Gisors.[152] The king referred to Joyeuse in the letters justifying the appointment as his most trusted brother in law. The duke of Elbeuf was infuriated by Joyeuse's appointment, of all the Lorraine family he had the most holdings in Normandie and had hoped to acquire the title for himself.[153] There was outrage too among the local Norman nobility, with various traditionally loyal nobles protesting the appointment of a man who was neither a prince nor Norman noble to the office.[152] Joyeuse would have to contend with the power of the Le Veneur and Moy families, which had not been significantly diminished despite the loss of the governorship.[154] Joyeuse for his part would have preferred Languedoc, where he could be sure of some familial strength, but unable to dislodge Montmorency therefore settled for Normandie.[155][156]

Despite not receiving the post officially until that date, awareness of his coming appointment was present prior, as such Joyeuse made his entry into Rouen as the governor of the province on 25 March of that year and was received with a banner that celebrated the possibility 'afflicted Normandie' might now be in safe hands.[157] He was accompanied on his entrance by the cream of the Norman nobility.[152] Shortly thereafter he left Rouen and travelled to Caen, where he was again received with elaborate festivities, including an allegorical painting which alluded to his role as Admiral by depicting him as Neptune. The position of the Caen elite was sensitive, with the leading men of the city aware of the bitterness of D'O about being relieved of his governate . It was feared D'O would attempt to seize the city in a coup.[158]

Joyeuse had difficulty with the Parlement in registering his appointment, as they protested that Norman liberties dictate that only the heir to the throne or a son of the king could be their governor. Alençon responded by claiming the governate for himself, which according to Le Roux therefore made Joyeuse's appointment a deliberate attempt of the king to limit his brothers ambitions.[159]

In April 1583 Henri went further, subordinating the governors of Rouen, Le Havre, Honfleur, Caen, Cherbourg and Granville to Joyeuse. The example of a previous governor of Normandie Admiral Annebault was deployed to justify this extraordinary arrangement. Despite all the power concentrated into his hands, Normandie would not be easy to govern. The province contained only four ordinance companies, and around 200 infantrymen in Rouen and Le Havre.[159]

Joyeuse worked quickly to make a good impression on the Norman nobility, making the king suppress a venal office which was much despised in Normandie. He also worked to impose his control. Back in late 1582, prior to becoming governor, Joyeuse had appointed his naval commander and relative Aymar de Chaste to the post of lieutenant of Caen. This would be followed in 1583 with the establishment of Chaste as lieutenant of Dieppe. He gained a further boon when two important offices were quickly vacated after his ascent, allowing him to choose replacements. The governor of Dieppe died and Joyeuse selected one of his relatives, Chaste to replace him. The following year on 21 June, he was able to take over the governate of Le Havre on the retirement of its incumbent, before choosing to sell the office to André de Brancas. In Caen he established a vicomte from Languedoc, Gaspard Pelet as governor and bailli (bailiff). Pelet was the guidon (Guide) of his ordinance company.[158][156]

With all of these centralising efforts, rumour swirled that Henri was planning to make Joyeuse the duke of Normandie.[156] The appointment of these men from outside the province would however sour things with the Norman nobility. Unlike other royal favourites, his Catholic credentials were impeccable, and this was an asset to him. That was until he appointed a former Protestant Claude Groulard as premier président (first president) of the Rouen Parlement in 1585. Groulard did not meet the age requirements of the office and his religious history was objectionable to elements of the nobility.[152] Despite this insult, Joyeuse would largely leave the Parlementaire dominated administration of Rouen alone, the contemporary de Thou interpreted this as a sign of his disinterest.[156]

Henri further eroded Joyeuse's reputation in the province in his efforts to cut down on the number of courtiers present at court, which had grown to around 8000 persons. He wrote to Joyeuse to urge him that Rouen did not need to send more than one merchant to represent their interests to the crown, and that if every town in France cut down like this royal expenses would be significantly reduced.[160] The king himself would visit Normandie, and Joyeuse attempted to convince his brother Cardinal Joyeuse to join him for his entry. The cardinal was displeased by Joyeuse's request, disliking involving himself in the domestic politics of France.[72]

Pilgrim

Joyeuse conducted a 'pilgrimage' to Italia in that year. He travelled at the king's expense with an escort of 30 cavalry men, in total the expedition would cost 100,000 livres.[161] He had been tasked by Henri with travelling to Loretto to intercede with the virgin Mary on Henri's behalf for the birth of an heir.[69] He had further cause to travel as his wife, Marguerite was ill, and he wished to pray for her recovery.[162] He took the opportunity of being in Italia to frequent Roma, entering the city on 1 July to a lavish reception from Cardinal d'Este. He fruitlessly tried to mobilise the Pope to take action against the duke of Montmorency, arguing that Montmorency was an ally of Protestantism.[13] He therefore pushed for the Pope to excommunicate Montmorency, but the Pope rebuffed him.[163] While efforts against Montmorency were unsuccessful, Joyeuse was able to convince the Pope to sanction a further alienation of church property, on the grounds that the money raised would be used for a new war against Protestantism.[164] His other effort concerning church land, the trading of the Comtat Venaissin for the French held marquisate of Saluzzo would not be successful. He also took the opportunity to campaign for his brother François to receive the cardinals hat. Though not having achieved much of what he wanted, Joyeuse left Roma satisfied on 13 July, travelling back to France via all the major cities of northern Italia, in each of which he functioned as something akin to an ambassador.[165]

Back at court Joyeuse reported sadly to the king that his expedition had largely been a failure. Indeed, historians have argued that for Joyeuse personally it was more of a failure than in his demands, as his several month absence from court had been used profitably by his rival Épernon.[165]

Montmorency

The aggressive opposition of Joyeuse to the great house of Montmorency occurred concurrently to Épernon declaring himself to be an enemy of the duke of Guise. By this means the two leading aristocratic pillars of previous regimes were attacked.[166]

Back in Languedoc Guillaume de Joyeuse continued to push for the king to dismiss Montmorency. Montmorency meanwhile complained incessantly that the duke of Joyeuse was going to have him assassinated. The dispute was still bubbling away in 1585 when Guillaume intercepted a letter in which Montmorency spoke disrespectfully of the king, describing him as engaging in 'unregulated love affairs'. When the king learned of this, he decided to formally dismiss Montmorency in September of that year. Guillaume entered Toulouse in triumph. Montmorency meanwhile accused Joyeuse of working towards his excommunication again, this time through the bishop of Paris. Not long after this though Henri decided that he had gone too far in the dismissal and alongside his mother Catherine began to work to reconcile at least somewhat with Montmorency as an ally against the ligueur (leaguer) party.[167] In the summer of 1587 Catherine succeeded in a coup, securing several marriage alliances with the Montmorency family. Bouchage was to marry Montmorency's daughter Marguerite de Montmorency, meanwhile Charlotte de Montmorency was to marry the bastard child of Charles IX. Guillaume de Joyeuse would refuse this reconciliation however, and join the ligue in 1589, while the king returned Languedoc to Montmorency formally in 1589.[82]

The chancellor René de Birague died in November 1583. Both Joyeuse and Épernon were keen to see that their man was chosen by the king to replace him. Joyeuse advocated for his own brother, François de Joyeuse. Épernon meanwhile pushed for the candidacy of the garde des sceaux Cheverny. In this competition between favourites, Épernon would triumph. In compensation to Joyeuse, Henri would secure François' elevation to cardinal.[168]

From November 1583 to February 1584 an Assembly of Notables convened to consider matters of finance. Among those in attendance were the princes du sang (Princes of the blood), officers of the crown, and representatives of both Épernon and Joyeuse. For Épernon his brother La Valette advocated the family interests, for Joyeuse his brother Bouchage.[169] They would consider various proposals for the financial reform of the kingdom. Their proposals would be taken seriously with the legislation passed by Henri throughout the year reflecting their suggestions. The king also reigned in his spending on their suggestion, with his budget almost becoming balanced in 1585.[170]

Joyeuse would receive further indications of royal favour during 1584. He was permitted to purchase the governate of the important port city of Le Havre inside his governate of Normandie, and was made governor of the duchy of Alençon upon the death of Alençon.[63][171]

Opposition

In July 1584, the king's brother, and heir to the throne, Alençon died. With his death, the succession defaulted to the distant cousin of the king Navarre, a Protestant. The prospect of Navarre's succession was seized upon by segments of the Catholic nobility (led by the duke of Guise) who used it as an excuse to re-found the Catholic Ligue (League).[172]

The favour shown to Joyeuse and Épernon greatly aggrieved segments of the French nobility.[173] Both men were subject to pointed criticism, without being explicitly named, in the Manifesto of Péronne issued by the reconstituted Catholic League for enabling the path to the throne of a 'heretic'.[174] The manifesto went on to accuse them of depriving nobles of their rightful titles and others of their offices so as to monopolise authority over the army. [175] Indeed opposition to Henri's choice of favourites proved a great driver in the movement at the aristocratic level.[176]

Increasingly concerned by the rumblings of opposition, Henri undertook to establish a new bodyguard. This new bodyguard would be known as the quarante-cinq (Forty Five). The members of the new bodyguard were selected by Épernon and Joyeuse from among their various vassals and clients in the noblesse seconde (secondary nobility). Of the 45 men, 35% would be of Gascon extraction, while 27% would be from Joyeuse's power base in eastern Languedoc.[177] The two men provided money to the new bodyguards so that they might buy the horses necessary to fulfil their duties.[178] As he brought forth this new institution, Henri dismissed many in his court, further swelling the ranks of the opposition who derided the quarante-cinq as a collection of 'low-born Gascon thugs'.[179] The English ambassador for his part characterised it as an institution primarily designed to protect the favourites themselves.[180] Having played a great role in the foundation of the institution, Joyeuse would also have a roll to play in its leadership. When the English ambassador the Earl of Derby visited in 1585 to present the king with the English Order of the Garter, Joyeuse took charge of the quarante cinq which guarded the king's chamber and afforded Derby his entrance.[181]

Joyeuse was afforded access to the conseil d'État (Council of State) by Henri towards the end of 1581. However unlike many other men that surrounded the king, he did not participate regularly. In total he would participate in the council only once, on 8 January 1585, outside of that he was absent.[182][183] Despite being included as an official member by the règlement de 1585 (rules of 1585), Joyeuse rarely attended the conseil des finances (Council of Finances). Naval matters would sometimes compel his presence, as when he evoked the expenditure of the Norman navy, or when he had matters to settle concerning the payment of Corsican sailors.[184] Joyeuse was on occasion admitted to the conseil ordinaire du roi (Ordinary Council of the king), however only if a matter concerned his interests.[185] He would however be a staple of the conseil privé (Private Council) where matters of sensitivity were discussed.[183] Much of the important decision making Henri undertook occurred outside the confines of formal council.[186]

Decline and death

War with the ligue

In March 1585 the ligue entered war with the crown. Henri was taken aback by the uprising, and some of those who joined its ranks. Among them was the governor of Berry La Châtre who had in prior months enjoyed a friendly meeting with Joyeuse and Épernon at which the two men had promised that they would gain for him the title of Marshal.[187] La Châtre had been without a patron since the death of Alençon, and Joyeuse had hoped to step into the role for the governor.[85] Henri quickly set to work planning a counter offensive against the various uprisings. Marshal D'Aumont was tasked with driving back the ligueurs in Orléans, the duke of Montpensier was named lieutenant-general of Poitou in the hopes he could combat the duke of Mercœur's influence there and Joyeuse was tasked with rooting out the Lorraine cousins Aumale and Elbeuf from Normandie. To support him in this effort he was given 600 foot soldiers and a company of light horse. His horse was commanded by Lavardin who would serve him regularly in the following years.[188][189] Lavardin had in previous years served with both the king of Navarre and the king's brother Alençon, therefore he was particularly keen to prove his loyalty to Henri and Joyeuse.[190]

His very appointment as governor of Normandie previously, had alienated the noblesse seconde families of Moy and Le Veneur, making them less keen to join in the fight against the Norman ligue.[152]

Henri was eager to see that Rouen did not fall to the rebels and to this end made plans for Joyeuse to conduct a royal garrison into the city in April. This attracted the outrage of the municipal 'council of twenty four' which protested strenuously to the king against this infringement on their urban liberties. Joyeuse joined the council in their opposition, seeing it as an opportunity to show himself as a representative of Norman interests, and the king backed down.[191][152] Joyeuse would ultimately have little chance to battle with the Norman ligueurs, however he would pursue the duke of Elbeuf out of the province, succeeding in bringing him into a skirmish on 17 June near Beaugency at which the prince of Lorraine was bested.[189] He would come out the better in the skirmish.[192] In the aftermath of the skirmish he wrote to the king of his victory, however he wrote with discomfort, as he was unsure if the king would approve of the damage he had done to the forces of the Lorraine prince and he asked for clarification on how he was to treat ligueurs.[193] Meanwhile, elsewhere in France, Mayenne seized Dijon, Mâcon and Auxonne while Guise took Toul and Verdun. Joyeuse's father would ensure that the family stronghold of Toulouse held for the royal cause. Indeed it was only the Midi that Henri could rely upon in the crisis.[194] After his victory at Beaugency, Joyeuse moved to link up with Montpensier, crossing the Dunois and Vendômois on the instructions of the king.[189]

Treaty of Nemours

In July peace was established in the Treaty of Nemours on favourable terms to the ligueurs, Henri agreed to make war on Protestantism, and granted various surety towns to the leading ligueurs.[192] He would not however take the peace lightly, and quickly set to work detaching various prominent ligueurs to the royalist camp. Among those targeted was the former governor of Caen, D'O who was allowed to re-enter the royal council and was made a chevalier du Saint-Esprit. He would however be dispossessed of the Château de Caen, which was given to a client of Joyeuse.[195] Joyeuse himself took on the role of patron to D'O, and on 14 January 1586 was able to secure the lieutenant-generalcy of lower Normandie for the errant favourite. He followed this two months later by securing for D'O the survivance to the governate of the Île de France (currently held by Villequier) on 20 March.[95]

Joyeuse and Épernon were key elements in the distribution of new fashions at court, as when in August 1585 the king became obsessed with playing with a cup and ball around court, both men adopted the use of the toy in imitation of him, which then permeated down through the nobility.[196] Joyeuse would also seek to imitate the king in the portraiture he had commissioned, asking the artist to show him in wearing clothing like that of the king.[197]

Alongside his political interests, Joyeuse also enriched himself through involvement in the financial administration of the kingdom. On 14 October 1585 he entered an agreement with the banker Sébastien Zamet for the collection of the gabelle, France's main salt tax. This enriched both the crown and Joyeuse.[198] In 1581 Joyeuse enjoyed a royal income of around 27000 livres, this had expanded to 152,000 livres by 1586. He further received rents and annuities in return for the financial services he performed for the crown.[199] In total across the 1580s, Joyeuse received around 2,500,000 livres in various forms of regular and irregular incomes. Meanwhile Épernon counted around 3,000,000 livres in that granted to him.[26] While royal favour brought many financial benefits to Joyeuse, it was also expected that the men around the king, Joyeuse among them, would act as the king's creditors. This would either be through the direct forwarding of money to the crown, or taking out loans on his behalf. In these matters, repayment was not always prompt, creating large financial liabilities that would subsume some around the king.[200]

Condé campaign

Compelled to fight the Protestants by the ligue, Joyeuse participated in the royal campaign against the Protestant prince of Condé who was campaigning vigorously in Poitou and Anjou in late 1585. He departed from the court in October to this affect with several hundred cavalry.[189] In this he would fight alongside the former ligueur La Châtre and his brother Bouchage who had been named governor of Anjou. Together they endeavoured to seize back the Château d'Angers which had been taken in a coup by Condé's agent Rochemorte. Condé rushed to provide support to Rochemorte but arrived too late, Rochemorte being dead and his garrison surrendered on 23 October.[201] Joyeuse almost succeeded in capturing the prince near Angers in a skirmish on 21 October and Condé was forced to flee first to Bretagne and then across the channel to London.[202] Joyeuse pursued, but was unable to capture the prince.[203] Though he would not himself campaign against the Protestants of Languedoc, he sent 150,000 écus (crowns) to his father for the prosecution of the war.[189] In the wake of this victory, Joyeuse returned to Paris in triumph to the adoration of much of the Catholic city. He was able to bask in the affections of the king, courtiers and much of the Catholic populace of Paris.[124] According to the Parisian diarist Pierre de l'Estoile it was a 'beautiful victory'. The king saw in him the potential for a new focal point of Catholic energies, pushing the ligue out of the spotlight.[204] With this temporary boon to Joyeuse's fortunes, Épernon was weakened, and Joyeuse pushed the attack, denouncing Épernon for his failure to demonstrate his worth on the field.[205]

On 1 February 1586, a ligueur prince, the duke of Nemours, arrived at the capital. Both Joyeuse and Épernon came out to greet him, but pointedly refused to dismount their horses to receive him as would have been expected by social convention. When, two weeks later, Guise arrived at the capital, neither man bothered to come out to greet him, and he was left to bask in the love of the population alone. Having arrived in the capital, Guise sought assurances that the recently captured citadel of Angers (which Joyeuse had bought in 1585 for 36,000 livres) would be given back to the ligueur comte de Brissac, however Joyeuse refused. Henri backed Joyeuse in this matter.[206]

With a new campaign soon to begin, Joyeuse saw potential to reinforce his credentials at the expense of his rival, Épernon. At this time, tensions became toxic in the capital, with Joyeuse openly lambasting the duke of Guise, accusing him of plotting to 'seize new places' under the cover of the peace. Both Joyeuse and Épernon had their apartments guarded by armed men, and Guise ceased to visit the Louvre at night, for fear of being attacked in the street. None of the three men wished to be the first to depart the capital, out of fear of leaving the city to their rivals. To this end Joyeuse announced that he would not visit his governate until Guise was out of Paris.[206] Around this time the focus of royal attention began to shift back towards Épernon, with the young favourite being allowed even to spend time with the king in the royal carriage. Realising his new advantage, he quickly worked to begin removing the influence of Joyeuse and Guise. Henri intended to use Épernon to achieve concord with the duke of Montpensier and House of Bourbon, with great success in securing Montpensier's loyalty to the crown. Thus Joyeuse functioned as the king's outreach to the Catholic ligueur nobility while Épernon's ties with the House of Bourbon allowed him to build bridges with the Protestants.[207]

The king saw advantage in increasing Joyeuse's control over the cavalry, in the hopes of diluting the authority of the ligueur duke of Nemours and duke of Guise over the institution. The former was colonel-general of the cavalry. Therefore Henri gave to Joyeuse twelve companies of light horse that were under his sole authority and were to function as 'troops of the guard of the king'. This greatly aggrieved Nemours and Guise.[66] Overall however the two favourites would not gain the dominance in the matter of 'cavalry' that they were able to secure in other military areas.[132]

Back in Normandie, Joyeuse faced opposition to his governorship from various malcontent nobles, aggrieved that they had been overlooked for appointment to various senior town governates. In opposition to this parochial ligues of nobles formed, ligues that were further aggrieved by his plan to install the rehabilitated royal favourite D'O as governor of Rouen in March 1586.[208] Many nobles refused to levy any soldiers for Joyeuse in defiance of this.[209]

By early 1586, Épernon was ascendent in the king's favour, while hopes of peace remained high. In her letters, the comtesse du Bouchage referred to him bitterly as the 'council of the king'. Henri therefore undertook to keep his two rivals, Guise and Joyeuse out of the capital. It was during this period that hatred between Épernon and Joyeuse would be at its most bitter.[210]

The critical port of Brouage was another settlement that Henri hoped to have under the control of Joyeuse. As such he sent entreaties to Jeanne de Cossé, wife of the governor, Saint-Luc, former favourite of the king. When Épernon learnt of these proposals he moved quickly to sabotage them, appealing to Cossé and Saint-Luc to resist the generous offer of 300,000 livres, a matter in which he would be successful.[206]

Auvergne campaign

He would command one of the main royal armies in Auvergne and Languedoc during the summer of 1586, allowing him to coordinate his action with his father in Languedoc, who was fighting with the duke of Montmorency.[211] The king had initially desired to give Admiral Joyeuse command of the forces at sea, however his grandmother wrote to the king to dissuade him from choosing Joyeuse for such a dangerous assignment 'more suited to other men'.[212] He committed large amounts of his own money to supporting the royal army he was commanding, totalling 114,000 livres for the force.[213] His departure from the royal court weighed heavily on the king, who held his hand until he mounted his horse to leave the court.[38] His command of this army was received at the expense of Marshal d'Aumont, who was at least theoretically in poor health.[214]

Joyeuse was thus at the head of a large army, totalling around 12,000 men, 1500 horse and 21 artillery pieces. Lavardin served as his maître de camp for the campaign.[214] It was hoped that he would be able to achieve juncture with his father's forces.[215] By putting his favourites at the head of the royal armies, instead of the ligueurs who had compelled him into war, he hoped to channel support for the Catholic ligue towards the royal cause. Joyeuse got off to a promising start on the campaign, which began in June, but quickly became bogged down on the road to the Aubrac which resisted with the support of the Velay, Rouergue and Gévaudan.[216] Opposition in the region was led by the son of Admiral Coligny, the seigneur de Châtillon who fought tenaciously. On 7 August he received the capitulation of Le Malzieu, and executed a dozen members of the garrison after its surrender. He justified himself by characterising them as 'wicked thieves'. He was able to obtain the capitulation of Marvejols and unleashed his troops on the town, who set to looting and burning despite the agreement he had made with the town for its surrender. During the siege he had sustained a wound to his head. On 31 August he lodged with the marquis de Canillac who led the ligueur presence in Auvergne. Canillac would accompany him for the remainder of the campaign.[214] On 7 September the Château de Peyre yielded to him after a siege. Lavardin took it upon himself to protect the Protestants of the settlement, to avoid any repeat of what had unfolded at Marvejols.[217] By the late autumn the rains made the roads impassable, and his troops were increasingly racked with illness. After having captured Eyssène on 4 November he entrusted the army to the new governor of the Rouergue Bertrand de Saint-Sulpice on 15 November and returned to court in failure.[218][217] No sooner had he departed than the Protestants seized Saint-Pons and Lodève.[219]The failures of the royal forces convinced many contemporaries that Henri was deliberately trying not to beat the 'heretics' out of fear that the end of heresy would strengthen the ligue.[220]

Meanwhile on the west coast the Protestants of La Rochelle had attempted a siege of Brouage. Joyeuse ordered that a naval army be prepared to relieve the important port.[133] Joyeuse took advantage of the authority afforded him by the office of Admiral to appoint his clients and relatives to positions of authority, for example his brother Antoine-Scipion was made lieutenant of the naval army that was to capture the Île de Ré from the Protestants in May 1586 with fourteen boats.[133] His main appointment for the navy would however be Aymar de Chaste who was made commander of the navy.[221]

Around this time, vice admiral Guy de Lansac was summoned to court, keeping him away from areas in which he had been threatening to cause seditions. He hoped to use the opportunity of being at court to conduct reorganisations of the navy, however he was frustrated in this by Aymar de Chaste, who held the authority of Admiral in the absence of Joyeuse while he was on campaign and was little interested in Lansac's ambitions.[222] Joyeuse's preference for Chaste would drive Lansac into support of the ligue.[221]

Épernon's profit

Épernon had used the months of Joyeuse's absence profitably, and by the time of Joyeuse's return after his campaigns in 1586 he lacked any political influence with the king, who was now largely committed to Épernons' project of reconciliation with Navarre. His primary utility to Henri had become that of a tool against Guise through military success in the field.[223] In response to his marginalisation Joyeuse began to turn to the ligueur princes for support. This only furthered Henri's displeasure with him, resulting in a lecture in February of 1587 for his association with Mayenne. In the estimation of the Savoyard ambassador Lucinge, Joyeuse lacked the desire to truly win and form a faction of the nobility truly devoted to his person as Épernon, Guise and Navarre had accomplished.[224] Guise for his part sort to advantage himself by the competition between Joyeuse and Épernon, but would be largely unsuccessful in using their rivalry to his own ends until the death of the former at Coutras.[225]