Annemarie Schwarzenbach | |

|---|---|

Schwarzenbach (photo by Anita Forrer, 1938) | |

| Born | Annemarie Minna Renée Schwarzenbach 23 May 1908 Zurich, Switzerland |

| Died | 15 November 1942 (aged 34) |

| Resting place | Friedhof Horgen, Horgen, Switzerland |

| Nationality | Swiss, after 1935 French |

| Other names | Annemarie Clarac / Clark |

| Education | University of Zurich |

| Occupation(s) | writer, journalist, photographer |

| Relatives | Alexis Schwarzenbach (great-nephew) |

Annemarie Minna Renée Schwarzenbach (23 May 1908 – 15 November 1942) was a Swiss writer, journalist and photographer. Her bisexual mother brought her up in a masculine style, and her androgynous image suited the bohemian Berlin society of the time, in which she indulged enthusiastically. Her anti-fascist campaigning forced her into exile, where she became close to the family of novelist Thomas Mann. She would live much of her life abroad as a photo-journalist, embarking on many lesbian relationships, and experiencing a growing morphine addiction. In America, the young Carson McCullers was infatuated with Schwarzenbach, to whom she dedicated Reflections in a Golden Eye. Schwarzenbach reported on the early events of World War II, but died of a head injury, following a fall.

Life

Annemarie Schwarzenbach was born in the city of Zurich, Switzerland. When she was four, the family moved to the Bocken Estate in Horgen, near Lake Zurich, where she grew up. Her father, Alfred, was a wealthy businessman in the silk industry. Her mother, Renée Schwarzenbach-Wille, the daughter of the Swiss general Ulrich Wille and descended from German aristocracy, was a prominent hostess, Olympic equestrian sportswoman and amateur photographer. Her father tolerated her mother's bisexuality.[1]

From an early age, she began to dress and act like a boy, a behaviour not discouraged by her parents and that she retained all her life. In fact, in later life, she was often mistaken for a young man.

At her private school in Zurich she studied mainly German, history and music, neglecting the other subjects. She liked dancing and was a keen piano player, but her heart was set on becoming a writer. She studied in Zürich and Paris and earned her doctorate in history at the University of Zurich at the age of 23. She started writing while still a student. Shortly after completing her studies, she published her first novella Freunde um Bernhard (Bernhard's Circle), which was well received.[1]

In 1930, she made contact with Erika and Klaus Mann (daughter and son of Thomas Mann). She was fascinated by Erika's charm and self-confidence. A relationship developed, which much to Schwarzenbach's disappointment did not last long (Erika had her eye on another woman: the actress Therese Giehse), although they always remained friends. Still smarting from Erika's rejection, she spent the following years in Berlin. There she found a soulmate in Klaus Mann and became a frequent visitor to the family Mann's house. With Klaus, she started using drugs. She led a fast life in the bustling, decadent, artistic city that was Berlin towards the close of the Weimar Republic. She lived in Westend, drove fast cars and threw herself into the Berlin night-life. "She lived dangerously. She drank too much. She never went to sleep before dawn", recalled her friend Ruth Landshoff. Her androgynous beauty fascinated and attracted both men and women.[2]

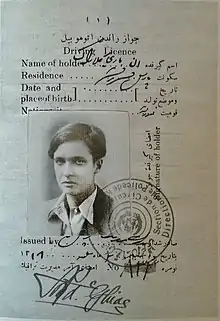

In 1932, Schwarzenbach planned a car trip to Persia with Klaus and Erika Mann and a childhood friend of the Manns, the artist Ricki Hallgarten. The evening before the trip was due to start, on 5 May, Ricki, suffering from depression, shot himself in his house in Utting on the Ammersee. For Schwarzenbach, this was the first time she encountered death directly.

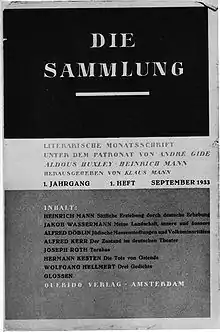

Schwarzenbach's lifestyle ended with the Nazi takeover in 1933, when bohemian Berlin disappeared. Tensions with her family increased, as some members sympathised with the far-right Swiss Fronts, which favoured closer ties with Nazi Germany. Her parents urged Schwarzenbach to renounce her friendship with the Manns and help with the reconstruction of Germany under Hitler. This she could not do, since she was a committed anti-Fascist and her circle included Jews and political refugees from Germany. Instead, later on, she helped Klaus Mann finance an anti-Fascist literary review, Die Sammlung, which helped writers in exile from Germany by publishing their articles and short stories.[3] The pressure she felt led her to attempt suicide, which caused a scandal among her family and their conservative circle in Switzerland.

She took several trips abroad with Klaus Mann, to Italy, France and Scandinavia, in 1932 and 1933. Also in 1933, she travelled with the photographer Marianne Breslauer to Spain to carry out a report on the Pyrenees. Marianne was also fascinated by Schwarzenbach: "She was neither a man nor a woman," she wrote, "but an angel, an archangel" and made a portrait photograph of her. Later that year, Schwarzenbach travelled to Persia. After her return to Switzerland, she accompanied Klaus Mann to the Soviet Writers Union Congress in Moscow. This was Klaus's most prolific and successful period as a writer. On her next trip abroad, she wrote to him suggesting their marrying, although she was a homosexual and he a bisexual. Nothing came of this proposal.

In 1935, she returned to Persia, where she married the French diplomat Achille-Claude Clarac, also a homosexual. They had known each other for only a few weeks, and it was a marriage of convenience for both of them, since she obtained a French diplomatic passport, which enabled her to travel without restrictions. They lived together for a while in Teheran, but when they fled to an isolated area in the countryside to escape the summer heat, their lonely existence had an adverse effect on Schwarzenbach. She turned to morphine, which she had been using for years for various ailments but to which she now became addicted.[1]

She returned to Switzerland for a holiday, taking in Russia and the Balkans by car. She had been interested in the career of Lorenz Saladin, a Swiss mountain-climber and photographer from a modest background who had scaled some of the most difficult peaks in the world. He had just lost his life on the Russian-Chinese border. From his contributions to magazines, she recognized the quality of his photographs. She was also fascinated by his fearless attitude about life and his confidence in the face of difficulties, which contrasted with her own problems with depression. When in Moscow, she acquired Saladin's films and diary and took them to Switzerland, with the intention of writing a book on him. However, once home, she could not face returning to the isolation she had experienced in Persia. She rented a house in Sils in Oberengadin, which became a refuge for herself and her friends. Here she wrote what was to become her most successful book, Lorenz Saladin: Ein Leben für die Berge (A Life for the Mountains), with a preface by Sven Hedin. She also wrote Tod in Persien (Death in Persia), which was not published until 1998, although a reworked version appeared as Das glückliche Tal (The Happy Valley) in 1940.

In 1937 and 1938, her photographs documented the rise of Fascism in Europe. She visited Austria and Czechoslovakia. She took her first trip to the USA, where she accompanied her American friend, photographer Barbara Hamilton-Wright, by car along the East Coast, as far as Maine. They then travelled into the Deep South and to the coal basins of the industrial regions around Pittsburgh. Her photographs documented the lives of the poor and downtrodden in these regions.

In June 1939, in an effort to combat her drug addiction and escape from the hovering clouds of violence in Europe, she embarked on an overland trip to Afghanistan with the ethnologist Ella Maillart. Maillart had "lorry-hopped" from Istanbul to India two years previously and had fond memories of the places encountered on that trip. They set off from Geneva in a small Ford car and travelled via Istanbul, Trabzon and Teheran and in Afghanistan took the Northern route from Herat to Kabul.

They were in Kabul when World War II broke out. In Afghanistan, Schwarzenbach became ill with bronchitis and other ailments, but she still insisted on travelling to Turkestan.[4]: 191 In Kabul, they split up, Maillart despairing of ever weaning her friend away from her drug addiction. They met once more in 1940 as Schwarzenbach was boarding the ship to return her to Europe. The trip is described by Maillart in her book The Cruel Way (1947), which was dedicated to "Christina" (the name Maillart used for the late Annemarie in the book, maybe at the demand of her mother, Renée).[5] It was made into a movie, The Journey to Kafiristan, in 2001.

She is reported to have had affairs with the Turkish Ambassador's daughter, who was suffering from tuberculosis, in Teheran and a female French archaeologist in Turkestan.[6][4]: 192 These were among the many affairs she had over the years.

After the Afghanistan trip, she travelled to the USA, where she again met her friends the Manns. With them, she worked with a committee for helping refugees from Europe. However, Erika soon decided to travel to London, which disappointed Schwarzenbach and she soon became disillusioned with her life in the USA. In the meantime, another complication had come into her life: in a hotel, she met the up-and-coming 23-year-old writer Carson McCullers, who fell madly in love with her ("She had a face that I knew would haunt me for the rest of my life", wrote McCullers). McCullers' passion was not reciprocated. In fact, she was devastated at Schwarzenbach's apparent lack of interest in her. Schwarzenbach, who had plenty of troubles herself, knew that there was no future in a one-sided relationship and avoided meeting with McCullers, but they remained friends. Later, they conducted a long and relatively tender correspondence, mainly on the subject of writing literature.[7] McCullers dedicated her novel, Reflections in a Golden Eye, which was actually written before the two women met, to her. Schwarzenbach was also at this time involved in a difficult relationship with the wife of a wealthy man, Baronessa Margot von Opel, and was still struggling with her feelings for Erika Mann.[8] This contributed to another bout of depression and another suicide attempt, which saw her hospitalised and released only under the condition that she leave the USA.

.jpg.webp)

In March 1941, Schwarzenbach arrived back in Switzerland, but she was soon on the move again. She travelled as an accredited journalist to the Free French in the Belgian Congo, where she spent some time but was prevented from taking up her position. In May 1942 in Lisbon, she met the German journalist Margret Boveri, who had been deported from the USA (her mother, Marcella O'Grady, was American). They liked each other personally, but Boveri was unimpressed by Schwarzenbach's work. In June 1942 in Tétouan, she met up again with her husband, Claude Clarac, before returning to Switzerland. While back home, she started making new plans. She applied for a position as a correspondent for a Swiss newspaper in Lisbon. In August, her friend the actress Therese Giehse stayed with her at Sils.

On 7 September 1942 in the Engadin, she fell from her bicycle and sustained a serious head injury, and following a mistaken diagnosis in the clinic where she was treated, she died on 15 November. During her final illness, her mother permitted neither Claude Clarac, who had rushed to Sils from Tétouan via Marseille,[4]: 223 nor her friends, to visit her in her sick bed. After Annemarie's death, her mother destroyed all her letters and diaries. A friend took care of her writings and photographs, which were later archived in the Swiss Literary Archives in Bern.

Throughout much of the final decade of her life, she was addicted to morphine and was intermittently under psychiatric treatment. She suffered from depression, which she felt resulted from a disturbed relationship with her domineering mother.[5] "She brought me up as a boy and as a child prodigy", Schwarzenbach recalled later of her mother. "She deliberately kept me alone, to keep me with her […]. But I could never escape her, because I was always weaker than her, but, because I could argue my case, felt stronger and that I was right. And while I love her."[2] Her family problems were exacerbated by family members supporting National Socialist politicians, while Annemarie hated the Nazis.[1] Despite her problems, Schwarzenbach was productive: besides her books, between 1933 and 1942, she produced 365 articles and 50 photo-reports for Swiss, German and some American newspapers and magazines.

Schwarzenbach is portrayed by Klaus Mann in two of his novels: as Johanna in Flucht in den Norden (1934) and as the Angel of the Dispossessed in Der Vulkan (The Volcano, 1939).

Personal life

Love letters written to Carson McCullers from Schwarzenbach are at the Harry Ransom Center at the University of Texas at Austin.[9]

Major works

Schwarzenbach wrote in German. Three of her works have been translated to English by Seagull Books and are distributed by the University of Chicago Press;[10] see the bibliography in:

- Annemarie Schwarzenbach. Analysen und Erstdrucke. Mit einer Schwarzenbach-Bibliographie. Eds. Walter Fähnders / Sabine Rohlf. Bielefeld: Aisthesis 2005. ISBN 3-89528-452-1

- Das glückliche Tal (new edition Huber Verlag, 2001, ISBN 3-7193-0982-7)

- Lyrische Novelle, 1933 (new edition Lenos, 1993, ISBN 3-85787-614-X)

- (original cover and illustrations by Jack von Reppert-Bismarck)

- Bei diesem Regen (new edition Lenos, 1989, ISBN 3-85787-182-2)

- Jenseits von New York (new edition Lenos, 1992, ISBN 3-85787-216-0)

- Freunde um Bernhard (new edition Lenos, 1998, ISBN 3-85787-648-4)

- Tod in Persien (new edition Lenos, 2003, ISBN 3-85787-675-1)

- Death in Persia (Seagull Books, 2013, ISBN 978-0-8574-2-089-3 English

- Auf der Schattenseite (new edition Lenos, 1995, ISBN 3-85787-241-1)

- Flucht nach oben (new edition Lenos, 1999, ISBN 3-85787-280-2)

- Alle Wege sind offen (new edition Lenos, 2000, ISBN 3-85787-309-4)

- Winter in Vorderasien (new edition Lenos, 2002, ISBN 3-85787-668-9)

- 'Georg Trakl. Erstdruck und Kommentar', hrsg. v. Walter Fähnders u. Andreas Tobler. In: Mitteilungen aus dem Brenner-Archiv 23/2004, S. 47–81

- 'Pariser Novelle' [Erstdruck aus dem Nachlaß, hrsg. v. Walter Fähnders]. In: Jahrbuch zur Kultur und Literatur der Weimarer Republik 8, 2003, S. 11–35.

- Unsterbliches Blau (gemeinsam Ella Maillart und Nicolas Bouvier, new edition Scheidegger & Spiess, 2003, ISBN 3-85881-148-3)

- Wir werden es schon zuwege bringen, das Leben. (Briefe von A. Schwarzenbach an Klaus und Erika Mann, ISBN 3-89085-681-0)

- Orientreisen. Reportagen aus der Fremde. Ed. Walter Fähnders. Berlin: edition ebersbach, 2010. ISBN 978-3-86915-019-2

- Das Wunder des Baums. Roman. Ed. Sofie Decock, Walter Fähnders, Uta Schaffers. Zürich: Chronos, 2011, ISBN 978-3-0340-1063-4.

- Afrikanische Schriften. Reportagen – Lyrik – Autobiographisches. Mit dem Erstdruck von "Marc". Ed. Sofie Decock, Walter Fähnders und Uta Schaffers. Chronos, Zürich 2012, ISBN 978-3-0340-1141-9.

- 'Frühe Texte von Annemarie Schwarzenbach und ein unbekanntes Foto: Gespräch / Das Märchen von der gefangenen Prinzessin / "mit dem Knaben Michael." / Erik'. In: Gregor Ackermann, Walter Delabar (Hrsg.): Kleiner Mann in Einbahnstrassen. Funde und Auslassungen. Aisthesis, Bielefeld: 2017 (= JUNI. Magazin für Literatur und Kultur. Heft 53/54), ISBN 978-3-8498-1225-6, S. 152–182.

Bibliography

- Grente, Dominique; Nicole Müller (1989). L'Ange inconsolable. Une biographie d'Annemarie Schwarzenbach (in French). France: Lieu Commun.

- Georgiadou, Areti (1995). Annemarie Schwarzenbach, Das Leben zerfetzt sich mir in tausend Stücke. Biographie (in German). Frankfurt: Campus Verlag.

- Miermont Dominique, Annemarie Schwarzenbach ou le mal d'Europe, Biographie. Payout, Paris, 2004.

- Walter Fähnders / Sabine Rohlf, Annemarie Schwarzenbach. Analysen und Erstdrucke. Mit einer Schwarzenbach-Bibliographie. Aistheisis Verlag, Bielefeld, 2005. ISBN 3-89528-452-1

- Walter Fähnders, In Venedig und anderswo. Annemarie Schwarzenbach und Ruth Landshoff-Yorck, In: Petra Josting / Walter Fähnders, "Laboratorium Vielseitigkeit". Zur Literatur der Weimarer Republik, Aisthesis, Bielefeld, 2005, p. 227–252. ISBN 3-89528-546-3.

- Walter Fähnders und Andreas Tobler: Briefe von Annemarie Schwarzenbach an Otto Kleiber aus den Jahren 1933–1942. In: Zeitschrift für Germanistik 2/2006, S. 366–374.

- Walter Fähnders: "Wirklich, ich lebe nur wenn ich schreibe." Zur Reiseprosa von Annemarie Schwarzenbach (1908–1942). In: Sprachkunst. Beiträge zur Literaturwissenschaft 38, Wien 2007, 1. Halbband, S. 27–54.

- Walter Fähnders, Helga Karrenbrock: "Grundton syrisch". Annemarie Schwarzenbachs "Vor Weihnachten" im Kontext ihrer orientalischen Reiseprosa." In: Wolfgang Klein, Walter Fähnders, Andrea Grewe (Hrsg.): "Dazwischen. Reisen – Metropolen – Avantgarden." Aisthesis, Bielefeld 2009 (Reisen Texte Metropolen 8), ISBN 978-3-89528-731-2, S. 82–105.

- Walter Fähnders: Neue Funde. Annemarie Schwarzenbachs Beiträge im Argentinischen Tageblatt (1933 bis 1941). In: Gregor Ackermann, Walter Delabar (Hrsg.): Schreibende Frauen. Ein Schaubild im frühen 20. Jahrhundert. Aisthesis, Bielefeld 2011, ISBN 978-3-89528-857-9, S. 193–198.

- Walter Fähnders, Uta Schaffers: "Ich schrieb. Und es war eine Seligkeit." Dichterbild und Autorenrolle bei Annemarie Schwarzenbach. In: Gregor Ackermann, Walter Delabar (Hrsg.): Kleiner Mann in Einbahnstrassen. Funde und Auslassungen. Aisthesis, Bielefeld 2017 (JUNI. Magazin für Literatur und Kultur. Heft 53/54)., ISBN 978-3-8498-1225-6, S. 119-151.

- Alexandra Lavizzari, "Fast eine Liebe - Carson McCullers und Annemarie Schwarzenbach," edition Ebersbach & Simon, Berlin, 2017 (ISBN 978-3-86915-139-7

- Alexis Schwarzenbach, Die Geborene. Renée Schwarzenbach-Wille und ihre Familie, Scheidegger & Spiess, Zurich, 2004. ISBN 3-85881-161-0

- Alexis Schwarzenbach, Auf der Schwelle des Fremden. Das Leben der Annemarie Schwarzenbach, Collection Rolf Heyne, München, 2008. ISBN 978-3-89910-368-7[11][12]

- Bettina Augustin, Der unbekannte Zwilling. Annemarie Schwarzenbach im Spiegel der Fotografie, Brinkmann und Bose, Berlin, 2008. ISBN 978-3-940048-03-5

- Die vierzig Säulen der Erinnerung. Mit einem Nachwort von Walter Fähnders. Golden Luft Verlag, Mainz 2022, ISBN 978-3-9822844-0-8.

References

- 1 2 3 4 Leybold-Johnson, Isobel. "Swiss writer's life was stranger than fiction". SWI swissinfo.ch. Retrieved 22 June 2017.

- 1 2 Alexis Schwarzenbach (15 May 2008). "Dieses bittere Jungsein". Die Zeit (in German). Retrieved 10 August 2008.

- ↑ Naumann, Uwe (1984). Klaus Mann (in German). Rowohlt. p. 64. ISBN 3-499-50332-8.

- 1 2 3 Georgiadou, Areti (1996). Das Leben zerfetzt sich mir in tausend Stücke. Annemarie Schwarzenbach (in German). Campus Verlag. ISBN 3-593-35350-4.

- 1 2 Maillart, Ella (1947). The Cruel Way. London: Heinemann.

- ↑ "Annemarie Schwarzenbach: A Life". Swiss Institute of Contemporary Art. 2002. Retrieved 17 August 2007.

- ↑ Griffin, Gabrielle (2002). Who's Who in Lesbian and Gay Writing. Routledge. p. 125. ISBN 0-415-15984-9.

- ↑ Carr, Virginia Spencer; Tennessee Williams (2003). The Lonely Hunter. University of Georgia Press. p. 105. ISBN 0-8203-2522-8.

- ↑ O’Grady, Megan (4 February 2020). "She Found Carson McCullers's Love Letters. They Taught Her Something About Herself". The New York Times. Retrieved 8 August 2022.

Shapland was an intern at the Harry Ransom Center, a writers' and artists' archive at the University of Texas at Austin, when she discovered love letters written to McCullers from Annemarie Clarac-Schwarzenbach, a Swiss heiress with whom McCullers had an affair.

- ↑ "Annemarie Schwarzenbach". University of Chicago Press. Retrieved 9 August 2022.

- ↑ Smith, Morelle (2021). The buoyancy of the craft: the writing and travels of Annemarie Schwarzenbach (1st ed.). UK: diehard literature. ISBN 978-1-913106-57-7. Retrieved 30 April 2021.

- ↑ Schwarzenbach, Alexis. "Auf der Schwelle des Fremden". Collection Rolf Heyne. Archived from the original on 6 December 2008. Retrieved 9 August 2022.

Further reading

- Robertson, Julia Diana (25 July 2017). "Annemarie Schwarzenbach—The Forgotten Woman—Activist, Writer & Style Icon". HuffPost.

External links

- Literary estate of Annemarie Schwarzenbach, HelveticArchives, Swiss National Library

- Publications by and about Annemarie Schwarzenbach in the catalogue Helveticat of the Swiss National Library

- Literature by and about Annemarie Schwarzenbach in the German National Library catalogue

- Barbara Lorey de Lacharrière. "Annemarie Schwarzenbach: A Life" from the Swiss Institute

- Der Engel Zum 100. Geburtstag von Annemarie Schwarzenbach

- Marianne Breslauer. Photos of Annemarie Schwarzenbach

- Annemarie Schwarzenbach.eu

- by and about Annemarie Schwarzenbach in the catalog of the National Library of Israel