| Part of a series on |

| Antisemitism |

|---|

|

|

|

Antisemitism in the United Kingdom signifies hatred of and discrimination against Jews in the United Kingdom.[1] Discrimination and hostility against the community since its establishment in 1070 resulted in a series of massacres on several occasions and their expulsion from the country in 1290. They were readmitted by Oliver Cromwell in 1655.

In the 19th century, increasing toleration of religious minorities gradually eliminated legal restrictions on public employment and political representation. However, Jewish financiers were seen by some as having an undue influence on government policy, particularly regarding the British Empire and foreign affairs.

Significant Jewish immigration from Eastern Europe in the years prior to World War I generated some opposition and resulted in increasingly restrictive immigration laws. Similarly, an emerging fascist movement in the 1930s which launched antisemitic campaigns was accompanied by a government policy of restricting the inflow of Jewish refugees from Nazi controlled territories. Notwithstanding sympathy for the Jews following the Holocaust, immigration controls to Mandatory Palestine were maintained, while Zionist attacks on British forces in Palestine in 1947 caused some resentment.

In the second half of the 20th century, while the Jewish community became generally accepted, antisemitic sentiment persisted within British fascist and other far-right groups. In the 21st century, while the level of antisemitism is amongst the lowest in the world, there is a trend of increasing antisemitic expression from individuals, much of it on social media and relating to Israel. Antisemitism is more prevalent among British Muslims, while anti-Zionism is associated with Muslims and the political left.

History

11th to 13th centuries: Persecution and expulsion

Jews arrived in the Kingdom of England following the Norman Conquest in 1066.[2] The earliest Jewish settlement was recorded in about 1070.[3]

Jews living in England from about King Stephen's reign (reigned 1135–1154) experienced religious discrimination while Jewish moneylending activity was strictly controlled and heavily taxed.[3] It is thought that the blood libel which accused Jews of ritual murder originated in England in the 12th century: examples include Harold of Gloucester, Little Saint Hugh of Lincoln, Robert of Bury and William of Norwich. In 1181, the Assize of Arms forbade Jews from owning a hauberk or chain mail. The York Massacre of 1190, one of a series of massacres of Jews across England, resulted in an estimated 150 Jews taking their own lives or being immolated.[4] The earliest recorded images of antisemitism are found in the Royal tax records from 1233.[5]

In 1253, Henry III enacted the Statute of Jewry placing a range of restrictions on Jews, including segregation and the wearing of a yellow badge. Its practical application is not recorded.[6] In 1264–7, the Second Barons' War included a further series of massacres of Jews with the objective of destroying the records of debts held by moneylenders.[7][8] In 1275, Edward I enacted the similar Statute of the Jewry, which included the outlawing of usury.[9] The first dated portrait of an English Jew is the 1277 antisemitic caricature Aaron, Son of the Devil,[10] in which he wears the English yellow badge (two tablets) on his upper garments.[11] After being expelled from a number of towns during previous decades, this early Jewish presence in England ended with King Edward I's Edict of Expulsion in 1290.[12] Subsequently, converted Jews were allowed to live in the Domus Conversorum (house of the converted) with records up to at least 1551.

17th to 19th centuries: Readmittance and emancipation

Jews were readmitted to the United Kingdom by Oliver Cromwell in 1655, though it is believed that crypto-Jews lived in England prior to that time.[3] Jews were subjected to discrimination and humiliation which waxed and waned over the centuries, gradually declining as Jews made commercial, philanthropic and sporting contributions to the country.[3]

.jpg.webp)

However, Jews were restricted by laws aimed primarily at Catholics and nonconformists, such as the Corporation Act 1661 and other Test Acts, which restricted public offices in England to members of the Church of England. The Jewish Naturalisation Act, which allowed Jews to become naturalised by application to Parliament, received royal assent on 7 July 1753 but was repealed in 1754 due to widespread opposition to its provisions.[13] For the purpose of Catholic emancipation, the test acts were repealed in 1828 but replaced by George IV with the Oath of Abjuration Act, which declared an oath of abjuration, containing the words "upon the faith of a Christian," to be necessary for all officers, civil or military, under the crown or in the universities, and for all lawyers, voters, and members of Parliament.[14]

Despite these restrictions, it has been suggested by William D. Rubinstein that antisemitism was lower in the United Kingdom than in a number of other European countries and that this was so for a number of reasons: Protestants shared with Jews an emphasis on the Old Testament, a self-perception as a chosen people with a direct covenant with God, and a distrust of Catholicism; with fewer Jews in the UK, Jews had a lesser commercial and financial role than in some other countries, reducing both real and perceived conflicts, and; Britain's early adoption of constitutional government with liberal principles acted to promote individual and civil liberties.[15]

In 1846, at the insistence of Irish leader Daniel O'Connell, the obsolete 1275 law, "De Judaismo", was repealed.[16] There continued to be opposition to emancipation from figures such as Thomas Carlyle who believed that all Jews should be expelled to Palestine, disliking what he perceived as Jews' materialism and archaic forms of religion.[17] In 1858, the Jews Relief Act 1858 removed the restriction of the oath of office for the Parliament to Christians, allowing Jews to become MPs. In 1871, the Universities Tests Act abolished the requirement for university staff and students to be adherents of the Church of England. In 1890, under the Religious Disabilities Removal Bill, all restrictions for every position in the British Empire were removed being thrown open to every British subject without distinction of creed, except for that of monarch and the offices of Lord High Chancellor and of Lord Lieutenant of Ireland.

1900s to 1920s: Finance and immigration

During the Second Boer War (1899–1902), some opposed to the war asserted that Jewish gold mining operators and financiers with their large stakes in South Africa were a driving force behind it, with Labour leader Keir Hardie asserting that Jews were part of a secretive "imperialist" cabal that promoted war.[18] The Independent Labour Party, Robert Blatchford's newspaper The Clarion, and the Trade Union Congress all blamed "Jewish capitalists" as "being behind the war and imperialism in general".[19] John Burns, a Liberal Party socialist, speaking in the House of Commons in 1900, asserted that the British Army itself had become "a janissary of the Jews".[20] Henry Hyndman also argued that "Jewish bankers" and "imperialist Judaism" were the cause of the conflict.[21] J. A. Hobson held similar views.[22][23][24] According to one historian, "The Jew baiting at the time of the Boer War and the Marconi scandal was linked to a broader protest, mounted in the main by the Radical wing of the Liberal Party, against the growing visibility of successful businessmen in national life and the challenges. What were seen as traditional English values."[25]

From 1882 to 1919, Jewish numbers in Britain increased fivefold, from 46,000 to 250,000, due to the exodus from Russian pogroms and discrimination, many of whom settled in the East End of London.[3][26] By the turn of the century, a popular and media backlash had begun.[27] The British Brothers' League was formed, with the support of prominent politicians, organising marches and petitions.[27] At rallies, its speakers said that Britain should not become "the dumping ground for the scum of Europe".[27] In 1905, an editorial in the Manchester Evening Chronicle[27] wrote "that the dirty, destitute, diseased, verminous and criminal foreigner who dumps himself on our soil and rates simultaneously, shall be forbidden to land". Antisemitism broke out into violence in South Wales in 1902 and 1903 where Jews were assaulted.[28] One of the main objectives of the Aliens Act in 1905 was to control such immigration.[27] Restrictions were increased in the Aliens Restriction Act 1914 and the immigration laws of 1919.[29]

In addition to anti-immigration campaigners, there were antisemitic groups, notably The Britons, launched in 1919,[30] which called for British Jews to be deported en masse to Palestine. In 1920, the Morning Post published over 17 or 18 articles a translation of The Protocols of the Elders of Zion, which subsequently formed the basis of a book, The Cause of World Unrest, to which half the paper's staff contributed. Later exposed as a forgery, they were initially accepted, with a leader in The Times blaming Jews for World War I and the Bolshevik regime and calling them the greatest threat to the British Empire.[31]

1930s

Popular sentiment against immigration was used by the Imperial Fascist League and the British Union of Fascists to incite hatred against Jews in the 1930s. However, a planned fascist march through the east end of London, with its large Jewish population, had to be abandoned due to the Battle of Cable Street in 1936, where police trying to ensure the march could proceed failed to clear barricades erected and defended by unionised dock workers, socialists, anarchists, communists, Jews and other anti-fascists.[32][33] Other antisemitic organisations in the 1930s included the Militant Christian Patriots and the Right Club.

The Évian Conference in 1938, attended by 32 countries, failed to reach agreement on accepting Jewish refugees from Nazi Germany. While Britain eventually accepted 70,000 up to the outbreak of World War II, in addition to the 10,000 children on the Kindertransport, there were, according to British Jewish associations, more than 500,000 case files of Jews who were not admitted. Louise London, author of Whitehall and the Jews, 1933–1948, stated that "The (British immigration) process...was designed to keep out large numbers of European Jews – perhaps 10 times as many as it let in."[34]

It was difficult for the refugees to find work, regardless of their education, except as domestics.[35] This also meant that Jewish refugees who were physicians could not practise medicine, even though there was a shortage of health care providers.[36] Some of the concern was economic. During a period of high unemployment, the British were concerned about losing job opportunities due to the influx of refugees.[34]

German Jewish refugees were discouraged from speaking German and encouraged to assimilate into the culture, which was often accomplished at the expense of their personal history and identity. A law was enacted in the 1930s to ensure that no more than 5% of the total students in a school were Jewish, limiting the rate at which Jewish children could be admitted to state schools. The press, which was generally not supportive of refugees, incorrectly reported that there were more Jews in Britain than had been in Germany in the summer of 1938.[34] Kushner and Katharine Knox state in their book Refugees in an Age of Genocide, "Of all the groups in the 20th century, refugees from Nazism are now widely and popularly perceived as 'genuine', but at the time German, Austrian and Czechoslovakian Jews were treated with ambivalence and outright hostility as well as sympathy."[34]

World War II and its aftermath

When war was declared, Britain no longer allowed immigration from Nazi-controlled countries.[35] The Bermuda Conference of the Allies held in April 1943 held to consider the issue of European Jews, whether liberated or under Nazi rule,[37] by which time it was known that the Nazi regime intended to exterminate them where it could, did not result in agreement on practical steps, with the overriding focus remaining on winning the war.[38] Nevertheless, 10,000 Jews managed to find their way into Britain during the war.[35] Britain did not allow Jews to immigrate to Palestine, though some did so illegally.[37]

During the war, Ministry of Information intelligence reports found examples of prejudice against Jews, including refugees from Nazi-occupied Europe, in almost all parts of the country, with Jews being a "scapegoat as an outlet for emotional disturbances".[39]

Immediately following the war, a large number of refugees entered the UK, but few were Jewish Holocaust survivors as immigration policy barred Jews because it did not consider them easily assimilable. A cabinet minister argued in 1945 that "the admission of a further batch of refugees, many of whom would be Jews, might provoke strong reactions from certain sections of public opinion. There was a real risk of a wave of anti-semitic feeling in this country".[40] Nevertheless, in the aftermath of the Holocaust, undisguised, racial hatred of Jews became unacceptable in British society.[1]

Post-War

Anti-Jewish sentiments became widespread around 1947 in response to fighting between the British Army and Zionist groups in the British Mandate for Palestine.[41] In August 1947, after the hanging of two abducted British sergeants by the Irgun, there was widespread anti-Jewish rioting across the United Kingdom.[42]

Antisemitic activity from fascist groups, Jeffrey Hamm's British League of Ex-Servicemen and, later, Oswald Mosley's new fascist party, the Union Movement, included antisemitic speeches in public places, and from the rank-and-file fascists, attacks on Jews and Jewish property.[43] This resulted in the formation of the 43 Group, led by Jewish ex-servicemen, which, from 1945 to 1950, broke up far right meetings, infiltrated fascist groups, and attacked the fascists in street fighting.[44] In the 1960s, groups such as the British National Party, founded in 1960, and the National Socialist Movement, founded in 1962, maintained a far right tradition.

After lobbying by the Board of Deputies of British Jews,[45] Jews, along with other groups, received formal legal protection from the Race Relations Act 1965, which outlawed discrimination on the "grounds of colour, race, or ethnic or national origins" in public places in Great Britain, and from successor legislation.[46] However, far right groups, such as the National Front, founded in 1967, and a new British National Party, founded in 1982, continued to express antisemitic views.[47][48]

21st century

Analysis

Sources

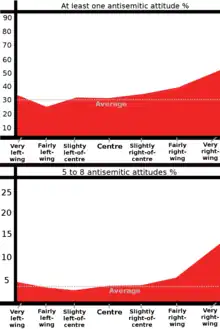

Antisemitic attitudes in the UK are higher amongst those on the far-right, and religious Muslims. Contemporary antisemitism is also prevalent on the left.[49][50][51]

Holocaust denial and antisemitic conspiracy theories remain core elements of far-right ideology.[48] A study into contemporary antisemitism in Britain by the Institute for Jewish Policy Research in September 2017 found that "The most antisemitic group on the political spectrum consists of those who identify as very right-wing: the presence of antisemitic attitudes in this group is 2 to 4 times higher compared to the general population."[53] The study stated that in "surveys of attitudes towards ethnic and religious minorities... The most consistently found pattern across different surveys is heightened animosity towards Jews on the political right..."[54] The Community Security Trust in 2018 found that far-right motivation or beliefs accounted for nearly one third of the 16% of incidents reported to them as antisemitic and with an identifiable political or ideological motivation.[55] According to a European Union Fundamental Rights Agency survey in 2018, victims in the UK, in instances where they ascribed a political viewpoint, perceived 20% of the perpetrators of the most serious attack or threat they had experienced to be "someone with a right-wing political view".[56] In 2016, research by the World Jewish Congress found that 90% of antisemitic posts on social media in the UK were made by white males under the age of 40 with affiliations to extreme right-wing groups.[57]

Some British Muslims, particularly Islamists, are significant contributors to antisemitism. The underlying roots are complex and include historic attitudes, domestic and political tensions, the Israeli–Palestinian conflict, and globalisation of the Middle East conflict.[58][59] According to Mehdi Hasan, "anti-Semitism isn't just tolerated in some sections of the British Muslim community; it's routine and commonplace".[60] A 2016 survey by the Institute for Jewish Policy Research found that the prevalence of antisemitic views among Muslims was two to four times higher than the rest of the population[61] and that there was a positive correlation between Muslim religiosity and antisemitism.[62] According to the Community Security Trust, in incidents where a physical description of the perpetrator was provided, 9% were described as being of Arab or North African appearance and a further 13% of south Asian appearance. However, very few incidents included Islamist expressions.[55] According to a European Union Fundamental Rights Agency survey in 2018, victims in the UK, in instances where they ascribed a political viewpoint, perceived 38% of the perpetrators of the most serious attack or threat they had experienced to be "someone with a Muslim extremist view".[63][56]

Anti-Zionism, principally, though not exclusively, from the left as well as from Muslims, has been associated with antisemitic incidents. The Community Security Trust in 2018 found that references to Israel accounted for nearly two-thirds of the 16% of antisemitic incidents with an identifiable political or ideological motivation.[55] Some comments allegedly criticising Israel are regarded by many as antisemitic. For some, contemporary anti-Zionism is itself a form of antisemitism. A study by the Institute for Jewish Policy Research in September 2017 found that "Levels of antisemitism among those on the left-wing of the political spectrum, including the far-left, are indistinguishable from those found in the general population. Yet, all parts of those on the left of the political spectrum exhibit higher levels of anti Israelism than average."[53] The report found that "...anti-Israel attitudes are not, as a general rule, antisemitic; but the stronger a person's anti-Israel views, the more likely they are to hold antisemitic attitudes. A majority of those who hold anti-Israel attitudes do not espouse any antisemitic attitudes, but a significant minority of those who hold anti-Israel attitudes hold them alongside antisemitic attitudes. Therefore, antisemitism and anti-Israel attitudes exist both separately and together."[64] The study stated that in "surveys of attitudes towards ethnic and religious minorities...The political left, captured by voting intention or actual voting for Labour, appears in these surveys as a more Jewish-friendly, or neutral, segment of the population."[54] According to a European Union Fundamental Rights Agency survey in 2018, victims in the UK in instances where they ascribed a political viewpoint, perceived 43% of the perpetrators of the most serious attack or threat they had experienced to be "someone with a left-wing view".[63][56]

Incidents

The majority of reports of antisemitic incidents are from areas where most Jews live: Metropolitan London, Greater Manchester and Hertfordshire.[65] Over 2014–18, around one fifth of the reported incidents occur on social media. The level typically rises following events related to Israel or the wider Middle East.[66] Thus the Community Security Trust reported a large rise after the 2014 Israel-Gaza conflict. More recently, the sharp rise in the number of reported incidents from 2016 onwards followed increased media coverage of antisemitism and may be an increase in actual incidents, or in reporting, or both. Around a quarter of reported incidents in 2018 took place on social media. The largest increases are in threats and abusive behaviour. The Trust believes that the total number of incidents is significantly higher than that reported.[67]

| Category | 1997 | 1998 | 1999 | 2000 | 2001 | 2002 | 2003 | 2004 | 2005 | 2006 | 2007 | 2008 | 2009 | 2010 | 2011 | 2012 | 2013 | 2014 | 2015 | 2016 | 2017 | 2018 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Extreme violence | 4 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 1 | 5 | 0 | 4 | 2 | 4 | 1 | 1 | 3 | 0 | 2 | 2 | 0 | 1 | 4 | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| Assault | 19 | 17 | 33 | 51 | 40 | 42 | 54 | 79 | 80 | 108 | 116 | 87 | 121 | 114 | 93 | 67 | 69 | 80 | 83 | 109 | 149 | 122 |

| Damage & desecration | 58 | 31 | 25 | 73 | 90 | 55 | 72 | 53 | 48 | 70 | 65 | 76 | 89 | 83 | 64 | 53 | 49 | 81 | 65 | 81 | 93 | 78 |

| Threats | 19 | 16 | 31 | 39 | 37 | 18 | 22 | 93 | 25 | 27 | 24 | 28 | 45 | 32 | 30 | 39 | 38 | 91 | 79 | 107 | 98 | 109 |

| Abusive behaviour | 86 | 136 | 127 | 196 | 122 | 216 | 211 | 272 | 273 | 365 | 336 | 317 | 609 | 391 | 412 | 467 | 374 | 899 | 717 | 1059 | 1065 | 1300 |

| Literature | 33 | 36 | 54 | 44 | 20 | 14 | 16 | 31 | 27 | 20 | 19 | 37 | 62 | 25 | 7 | 12 | 5 | 30 | 12 | 19 | 15 | 42 |

| Total | 219 | 236 | 270 | 405 | 310 | 350 | 375 | 532 | 455 | 594 | 561 | 546 | 931 | 646 | 609 | 650 | 535 | 1182 | 960 | 1375 | 1420 | 1652 |

In 2017–18 the police in England and Wales (excluding Lancashire) recorded 1191 antisemitic hate crimes, which excludes some behaviours recorded by the CST. Taking the Metropolitan Police data alone, the number rose by 15% in the following year, from 519 to 597. Comparisons with the Crime Survey for England and Wales suggest that less than half of hate crime is reported to the police.[69]

A 2018 survey by the European Union Agency for Fundamental Rights found that about a quarter of Jews in the UK had felt offended or threatened over the last year, increasing to one third over the last five years.[70] In the same survey, 24% of British Jews had witnessed other Jews being verbally insulted or harassed and/or physically attacked in the past 12 months, of whom 18% were family members. Only about one fifth of incidents were reported.[71]

Attitudes

Research published in June 2015 by the Pew Research Center showed that of, six countries participating, the population of the UK had almost the most favourable views of Jews. While 78% of these six European countries have a favourable opinion of Jewish people and 13% did not, 83% of the UK population hold positive views, and only 7% hold unfavourable opinions.[77]

In 2017 the Institute for Jewish Policy Research conducted what it called "the largest and most detailed survey of attitudes towards Jews and Israel ever conducted in Great Britain." The survey found that the levels of antisemitism in Great Britain were among the lowest in the world, with 2.4% expressing multiple antisemitic attitudes, and about 70% having a favourable opinion of Jews. However, only 17% had a favourable opinion of Israel, with 33% holding an unfavourable view.[78][79]

Discourse

Where a motivation was evident, incidents reported to the Community Security Trust split roughly between one third which are far-right and two-thirds which are anti-Israel. In other cases, the motivation is unclear because the perpetrator either did not communicate a clear rationale or used a combination of some or all of classic anti-semitic canards, Nazi references and anti-Israel expressions.[55] Some expressions criticising Israel are regarded by many as antisemitic. For some, criticism of Israel and anti-Zionism is itself a form of antisemitism.

Inquiries

In 2006, a group of British Members of Parliament held an inquiry into antisemitism at the time of the Second Intifada. Its report stated that "until recently, the prevailing opinion both within the Jewish community and beyond [had been] that antisemitism had receded to the point that it existed only on the margins of society." It found a reversal of this progress since 2000. The inquiry was reconstituted following a surge in antisemitic incidents in Britain during the summer of 2014, at the time of the 2014 Israel-Gaza conflict and published its report in 2015, making recommendations for reducing antisemitism.[80]

In 2016, the Home Affairs Select Committee held an inquiry into antisemitism in the UK.[81] The inquiry called party leaders and others to give evidence. Its report was critical of the Conservative Party, the Labour Party, the Chakrabarti Inquiry, the Liberal Democrats, the National Union of Students (particularly its then president Malia Bouattia), Twitter and police forces for variously exacerbating or failing to address antisemitism. The report made a series of recommendations, including the formal adoption by the UK government, with additional caveats (for example, on free speech),[82] of the International Holocaust Remembrance Alliance (IHRA)'s Working Definition of Antisemitism.[83]

Political parties

In 2015, 2016 and 2017, the Campaign Against Antisemitism (CAA) commissioned YouGov to survey British attitudes towards Jews.[84] The 2017 survey found that 30% of supporters of the Liberal Democrats endorsed at least one "antisemitic attitude", as defined by the CAA, compared with 32% of Labour supporters, 39% of UK Independence Party (UKIP) supporters and 40% of Conservative Party supporters.[84][85]

The 2016 Select Committee enquiry found that, although the threat that the far right posed to Jews had fallen, "Holocaust denial and Jewish conspiracy theories remain core elements of far-right ideology" and the British National Party (BNP) continues to stir up trouble and damages societal cohesion.[83] The report also provided evidence of antisemitism in the Conservative Party, including an alleged "toxic environment" in the UCL Conservative Society.

Allegations of antisemitism in the Labour Party have been made[86] since its members elected Jeremy Corbyn as leader in 2015, mostly due to his past associations with anti-Zionists. In 2016 Labour commissioned the Chakrabarti Inquiry, which found "no evidence" of systemic antisemitism in Labour, though there was an "occasionally toxic atmosphere".[87] The Select Committee in 2016 concluded that "...there exists no reliable, empirical evidence to support the notion that there is a higher prevalence of antisemitic attitudes within the Labour Party than any other political party". It also found that Jeremy Corbyn had shown a "lack of consistent leadership", which "has created what some have referred to as a 'safe space' for those with vile attitudes towards Jewish people" and that "The failure of the Labour Party to deal consistently and effectively with anti-Semitic incidents in recent years risks lending force to allegations that elements of the Labour movement are institutionally anti-Semitic."[83][88] In February and July 2019, Labour issued information on investigations into complaints of antisemitism against individuals, with around 350 members resigning, being expelled or receiving formal warnings, equating to around 0.08% of the membership.

Antisemitism is also alleged to exist in the Conservative and Liberal Democrat parties. For example, since the start in July 2019 of Boris Johnson's leadership of the Conservative party, senior Conservative politicians have been accused of antisemitism – including Jacob Rees-Mogg,[89] Priti Patel,[90] Crispin Blunt,[91] Michael Gove,[92] James Cleverly,[93] Theresa May,[94] and Johnson's advisor Dominic Cummings,[95] as have Liberal Democrat parliamentary candidates.[96] In an interview with the Sunday Times in January 2020, former House of Commons speaker John Bercow noted that, while he had never faced antisemitic abuse from Labour Party members, “I did experience antisemitism from members of the Conservative Party.”[97]

Responses

Government

The Home Office has provided 'The Jewish Community Protective Security Grant' for the security of synagogues, schools and other Jewish centres, with the Community Security Trust as the Grant Recipient. It was introduced in 2015 and Home Secretary, Sajid Javid pledged to increase funding, bringing the total amount allocated from 2015 to 2019 to £65.2 million.[98][99]

The Holocaust is the only compulsory subject in the national history curriculum in secondary schools.[100] The Department for Education provides significant funding to the Holocaust Educational Trust, including programmes for schools and universities. The Government also funds the Holocaust Memorial Day Trust.

The Heritage Lottery Fund in 2018 and 2019 provided significant funding for conservation and a religious, educational and cultural centre for Bevis Marks Synagogue,[101] to open Willesden Jewish Cemetery as a place of heritage for the public,[102] to open a Holocaust Education and Learning Centre in Huddersfield[103] and to refresh and expand the Beth Shalom Holocaust Centre in Nottinghamshire.[104] In August 2019, the Imperial War Museum announced plans to spend over £30m on a new set of galleries over two floors at its London site covering the Holocaust and its importance in World War II. The galleries are set to open in 2021 and will replace the existing permanent Holocaust exhibition.[105] The government is contributing £75m to the planned UK Holocaust Memorial.

The government is funding the anti-prejudice charities, the Anne Frank Trust and Kick it Out[69] and has provided significant funding via the Office for Students to tackle religious-based hate crime in higher education.[106] In September 2019, the government announced a grant of £100,000 to the Antisemitism Policy Trust to produce videos to combat antisemitism online.[107]

In September 2019, Robert Jenrick, the newly appointed Secretary of State for Housing, Communities and Local Government said "I will use my position as Secretary of State to write to all universities and local authorities to insist that they adopt the IHRA definition at the earliest opportunity...and use it when considering matters such as disciplinary procedures. Failure to act in this regard is unacceptable."[108]

Migration

According to surveys conducted by the Institute for Jewish Policy Research, the proportion of British Jews who had contemplated emigration due to antisemitism at some point in the previous five years was 18% in 2012, and 29% five years later in 2017. In the latter survey, three-quarters of those who had contemplated leaving said that they were considering moving to Israel. However, emigration to Israel fell by 11% between the two five-year periods and was much lower than the contemplated level, at 2899 people in total during 2008–2012 and 2579 in total during 2013–2017, or about 1% of the community during each five-year period.[109]

In December 2023, poll data collected by the Campaign Against Antisemitism indicates that nearly half of a "self-selecting" sample[110] of British Jews have considered leaving the UK in response to increased antisemitism following the 2023 Hamas attack on Israel.[111]

See also

References

- 1 2 Schoenberg, Shira. "United Kingdom Virtual Jewish History Tour." Jewish Virtual Library. 26 July 2017.

- ↑ Cardaun 2015, p. 37.

- 1 2 3 4 5 "ENGLAND - JewishEncyclopedia.com". www.jewishencyclopedia.com. Retrieved 17 October 2016.

- ↑ "BBC – Religions – Judaism: York pogrom, 1190". bbc.co.uk.

- ↑ Lipton, Sara (6 June 2016). "The First Anti-Jewish Caricature?". New York Review of Books. Retrieved 30 November 2017.

- ↑ Stacey 2003, p. 52

- ↑ Jacobs, Joseph (1906). "England". Jewish Encyclopedia. JewishEncyclopedia.com.

- ↑ Mundill 2010, pp. 88–99

- ↑ Prestwich, Michael. Edward I p 345 (1997) Yale University Press. ISBN 0-300-07157-4.

- ↑ Jacobs, Joseph; Wolf, Lucien (20 September 2012). Catalogue of the Anglo-Jewish Historical Exhibition, Royal Albert Hall, London, 1887. Cambridge University Press. p. 8. ISBN 978-1-108-05504-8.

- ↑ Jacobs, Joseph. "AARON, SON OF THE DEVIL". www.jewishencyclopedia.com. Jewish Encyclopedia. Retrieved 7 February 2016.

- ↑ "BBC – Religions – Judaism: Readmission of Jews to Britain in 1656". Retrieved 17 October 2016.

- ↑ Williams, Hywel (2005). Cassell's Chronology of World History. Weidenfeld & Nicolson. p. 316. ISBN 978-0-304-35730-7.

- ↑ Jacobs, Joseph. "England". Jewish Encyclopaedia. Retrieved 27 August 2019.

- ↑ Rubenstein, William D. (2010). Antisemitism in the English-Speaking World. New York: Oxford University Press Inc. p. 459.

- ↑ Jewish Ireland. Jewishireland.org

- ↑ Cumming, Mark (2004). The Carlyle Encyclopedia. Fairleigh Dickinson University Press. p. 252. ISBN 978-1611471724.

a Jew is bad but what is a Sham-Jew, a Quack-Jew? And how can a real Jew ... try to be Senator, or even Citizen of any Country, except his own wretched Palestine, whither all his thoughts and steps and efforts tend,-where, in the Devil's name, let him arrive as soon as possible, and make us quit of him!

- ↑ Wistrich 2012, pp. 203–205.

- ↑ Judd & Surridge 2013, p. 242.

- ↑ Wheatcroft 2018.

- ↑ Mcgeever, Brendan, and Satnam Virdee. "Antisemitism and Socialist Strategy in Europe, 1880–1917: An Introduction." Patterns of Prejudice 51.3–4 (2017): 229

- ↑ New Liberalism, Old Prejudices: J. A. Hobson and the "Jewish Question" John Allett Jewish Social Studies Vol. 49, No. 2 (Spring, 1987), pp. 99–114

- ↑ Doctrines Of Development, M. P. Cowen, Routledge, page 259, quote:"Rampant anti-Semitism should be recognized, not least because it is John A. Hobson, one of the most rabid anti-Semites of the period, who is the inspiration, alongside Schumpeter and Veblen, for...

- ↑ The Information Nexus: Global Capitalism from the Renaissance to the Present, Cambridge University Press, Steven G. Marks, page 10, quote: "And in England, the Social Democratic Federation newspaper Justice state that "the Jew financier" was the "personification of international capitalism" – an opinion repeated in the anti-Semitic diatribes of John A. Hobson, the socialist writer who wrote one of the earliest English books with "capitalism" in the title and helped to familiarize Britons with the concept"

- ↑ Todd M. Endelman (2002). The Jews of Britain, 1656 to 2000. p. 9. ISBN 9780520227194.

- ↑ "Jews in Britain – Timeline". Board of Deputies of British Jews. Archived from the original on 31 December 2019. Retrieved 31 August 2019.

- 1 2 3 4 5 David Rosenberg, 'Immigration' on the Channel 4 website

- ↑ David Cesarani, The Jewish Chronicle and Anglo-Jewry 1841–1991, (Cambridge, Cambridge University Press, 1994) p. 98.

- ↑ Louise London (27 February 2003). Whitehall and the Jews, 1933–1948: British Immigration Policy, Jewish Refugees and the Holocaust. Cambridge University Press. pp. 16–17. ISBN 978-0-521-53449-9.

The Aliens Restriction Act 1914 introduced sweeping powers to restrict alien immigration and to provide for deportation. After the war the Aliens Restriction (Amendment) Act 1919 extended the 1914 provisions into peace-time and added severe new restrictions.

- ↑ Toczek 2016, p. 83.

- ↑ Andre Liebich: "The Antisemitism of Henry Steed", Patterns of Prejudice, Vol. 46, No. 2, 2002. Retrieved 21 December 2016. Archived 10 August 2017 at the Wayback Machine

- ↑ Filby 2005, p. 56.

- ↑ Nachmani 2017, p. 88.

- 1 2 3 4 Anne Karpf (7 June 2002). "Immigration and asylum: We've been here before". The Guardian. Retrieved 1 July 2017.

- 1 2 3 "Great Britain" (PDF). Shoah Resource Center, The International School for Holocaust Studies, Yad Vashem.

- ↑ Elizabeth A. Atkins (2005). "'You must all be Interned': Identity Among Internees in Great Britain during World War II". Gettysburg Historical Journal. 4 (5): 63–66. Retrieved 8 April 2017 – via The Cupola: Scholarship at Gettysburg College.

- 1 2 "Refugees". Holocaust Encyclopedia, United States Holocaust Memorial Museum. Washington, D.C. Retrieved 1 July 2017.

- ↑ "Bermuda Conference" (PDF). The International School for Holocaust Studies, Yad Vashem. Retrieved 1 July 2017.

- ↑ Coughlan, Sean (11 September 2019). "When truth trumped propaganda in wartime". BBC News. Retrieved 11 September 2019.

- ↑ Karpf, Ann (8 June 2002). "We've been here before". The Guardian. Retrieved 1 September 2019.

- ↑ Macklin, Very Deeply Dyed in Black, pp. 45–46

- ↑ Jewish Chronicle 8/8/47 and 22/8/47, both p. 1. See also Bagon, Paul (2003). "The Impact of the Jewish Underground upon Anglo Jewry: 1945–1947". St Antony's College, University of Oxford M-Phil thesis (mainly the conclusion) Retrieved on 25 October 2008.

- ↑ Hillman, N. (2001). "Tell me chum, in case I got it wrong. What was it we were fighting during the war? The Re-emergence of British Fascism, 1945-58". Contemporary British History. 15 (4): 1–34. doi:10.1080/713999428. S2CID 143994809.

- ↑ Adam Lent "British Social Movements Since 1945: Sex, Colour, Peace and Power". Macmillan p19, ISBN 0-333-72009-1

- ↑ "Jews in Britain Timeline". Board of Deputies. Archived from the original on 31 December 2019. Retrieved 28 August 2019.

- ↑ "On this day: 8 December 1965: New UK race law 'not tough enough'". BBC News. 8 December 1965. Retrieved 10 January 2010.

- ↑ Billig 1978, p. v.

- 1 2 Goodwin 2011, pp. 38–39.

- ↑ Hirsh, David. 2017. Contemporary Left Antisemitism. Abingdon: Routledge. ISBN 9781138235304

- ↑ Antisemitism and the left: On the return of the Jewish question Philip Spencer, Robert Fine, Manchester University Press, 2018

- ↑ Philo, G., Berry, M., Schlosberg, J., Lerman, A., Miller, D. and Nava, M., 2019. Bad news for labour: Antisemitism, the party and public belief. Pluto Press.

- ↑ "Antisemitism in Contemporary Great Britain" (PDF). Institute for Jewish Policy Research. September 2017. p. 47. Retrieved 6 July 2019.

- 1 2 Staetsky 2017, p. 5–8.

- 1 2 Staetsky 2017, p. 42.

- 1 2 3 4 "ANTISEMITIC INCIDENTS REPORT 2018" (PDF). Community Security Trust. p. 9. Retrieved 28 August 2019.

- 1 2 3 "Experiences and perceptions of antisemitism" (PDF). Fundamental Rights Agency. 2018. p. 54. Retrieved 28 August 2019.

- ↑ "THE RISE OF ANTI SEMITISM ON SOCIAL MEDIA SUMMARY OF 2016". World Jewish Congress. p. 70. Retrieved 8 July 2019.

- ↑ "Report of the All-Party Parliamentary Inquiry into Antisemitism" (PDF). All-Party Parliamentary Group against Antisemitism. Archived from the original (PDF) on 22 August 2013. Retrieved 18 May 2013.

- ↑ Gunther, Jikeli. "Antisemitism Among Young Muslims in London" (PDF). International Study Group Education and Research on Antisemitism Colloquium I: Aspects of Antisemitism in the UK. Archived from the original (PDF) on 20 August 2016. Retrieved 25 May 2013.

- ↑ Hasan, Mehdi (21 March 2013). "The sorry truth is that the virus of anti-Semitism has infected the British Muslim community". The New Statesman.

- ↑ "British Muslims twice as likely to espouse anti-Semitic views, survey suggests". Jewish Telegraphic Agency. 12 September 2017.

- ↑ May, Callum (13 September 2017). "Over a quarter of British people 'hold anti-Semitic attitudes', study finds". BBC News.

- 1 2 Enstad, Johannes Due. "Antisemitic Violence in Europe, 2005–2015. Exposure and Perpetrators in France, UK, Germany, Sweden, Denmark and Russia." (2017).

- ↑ Staetsky 2017, p. 44.

- ↑ "Government Action on Antisemitism final 24 December" (PDF). GOV.UK. Department for Communities and Local Government Britain. Retrieved 17 January 2015.

- 1 2 "ANTISEMITIC INCIDENTS REPORT 2012" (PDF). Community Security Trust. Archived from the original (PDF) on 1 March 2014. Retrieved 18 May 2013.

- 1 2 "ANTISEMITIC INCIDENTS REPORT 2018" (PDF). Community Security Trust. Retrieved 28 August 2019.

- ↑ "ANTISEMITIC INCIDENTS REPORT 2006" (PDF). Community Security Trust. Archived from the original (PDF) on 29 September 2012. Retrieved 18 May 2013.

- 1 2 "Incidence of Antisemitism Worldwide Debate on 20 June 2019" (PDF). House of Lords. June 2019. Retrieved 28 August 2019.

- ↑ Kirby, Paul (10 December 2018). "Anti-Semitism pervades European life, says EU report". BBC News. Retrieved 28 August 2019.

- ↑ "Experiences and perceptions of antisemitism" (PDF). Fundamental Rights Agency. 2018. p. 56. Retrieved 28 August 2019.

- ↑ "Attitudes Toward Jews, Israel and the Palestinian-Israeli Conflict in Ten European Countries – April 2004" (PDF). ADL. Archived from the original (PDF) on 7 April 2014. Retrieved 25 May 2013.

- ↑ "Attitudes Toward Jews in Twelve European Countries – May 205" (PDF). ADL. Archived from the original (PDF) on 7 January 2014. Retrieved 25 May 2013.

- ↑ "Attitudes Toward Jews and the Middle East in Six European Countries – July 2007" (PDF). ADL. Archived from the original (PDF) on 3 December 2013. Retrieved 25 May 2013.

- ↑ "Attitudes Toward Jews in Seven European Countries – February 2009" (PDF). ADL. Archived from the original (PDF) on 7 April 2014. Retrieved 25 May 2013.

- ↑ "Attitudes Toward Jews in Ten European Countries – March 2012" (PDF). ADL. Archived from the original (PDF) on 12 May 2013. Retrieved 25 May 2013.

- ↑ Stokes, Bruce (2 June 2015). "Faith in European Project Reviving". PEW research center. PEW research center. Retrieved 29 June 2015.

- ↑ May, Callum (13 September 2017). "Over a quarter of British people 'hold anti-Semitic attitudes', study finds". BBC News. Retrieved 16 September 2017.

- ↑ L. Daniel Staetsky (September 2017). Antisemitism in contemporary Great Britain (PDF) (Report). Institute for Jewish Policy Research. Archived from the original (PDF) on 14 September 2017. Retrieved 16 September 2017.

- ↑ "Key recommendations include call for police and council involvement". www.thejc.com. Retrieved 23 August 2016.

- ↑ "Inquiry on anti-Semitism launched – News from Parliament". UK Parliament. Retrieved 17 October 2016.

- ↑ Bindman, Geoffrey (27 July 2018). "How should antisemitism be defined?". The Guardian.

The IHRA definition is poorly drafted and has led to the suppression of legitimate debate

- 1 2 3 Antisemitism in the UK, Tenth Report of Session 2016–17. Report, together with formal minutes relating to the report (PDF) (Report). House of Commons Home Affairs Committee. 13 October 2016. Retrieved 24 December 2022.

- 1 2 "Antisemitism Barometer 2017" (PDF). Campaign Against Antisemitism. Retrieved 27 March 2018.

- ↑ Beware cherry-picked stats on Labour and antisemitism, Channel 4 FactCheck, 25 April 2018

- ↑ Green, Dominic (30 November 2019). "Allegations of anti-Semitism are damaging to Labour, but not toxic". The Spectator. Retrieved 26 December 2019.

- ↑ Seymour 2018a.

- ↑ ITV (16 October 2016). "Labour accused of 'incompetence' in dealing with anti-Semitism allegations". ITV. Retrieved 30 November 2017.

- ↑ N. Broda, 'We need to talk about the Tories' antisemitism problem' (03/10/19) on Jewish News

- ↑ M. Frot, 'JLM lambasts Priti Patel for 'North London metropolitan liberal elite' comment' (02/10/9) in Jewish News

- ↑ Lee Harpin, 'Conservative MP accuses chief rabbi of demanding 'special status' for Britain's Jews' (02/10/19) in The Jewish Chronicle

- ↑ Antony Lerman, 'The Tories are exploiting Jewish fears over antisemitism' (09/11/19) in Open Democracy

- ↑ Antony Lerman, ''Who's behind the 'dark money' bankrolling our politics?' (09/11/2019) in Open Democracy

- ↑ E. Brazell, 'Theresa May under fire after unveiling statue of 'Nazi-sympathising' MP (29 November 2019) in Metro

- ↑ M. Greene, 'If Boris Johnson really cared about Jews, he'd stop using us to distract from his own bigotry' (31 November 2019) on The Independent

- ↑ J. Lansman, 'Focusing only on Labour whitewashes the antisemitism and racism of other parties' (20 November 2019) on The Jewish Chronicle

- ↑ Giordano, Chiara (3 February 2020). "John Bercow says he was subject to antisemitic abuse from Conservatives". The Independent. Archived from the original on 7 May 2022. Retrieved 3 February 2020.

I remember a member saying, 'If I had my way, Berkoff, people like you wouldn't be allowed in this place.' And I said, 'Sorry, when you say people like me, do you mean lower-class or Jewish?' To which he replied, 'Both.'

- ↑ "Home Office raises grant for protection of Jewish institutions by £600,000". The Jewish Chronicle. 27 February 2019. Retrieved 27 February 2019.

- ↑ "Sajid Javid vows to tackle anti-Semitism in UK". BBC New. 27 February 2019. Retrieved 27 February 2019.

- ↑ Whitehouse, Rosie (16 October 2018). "The Failure of Holocaust Education in Britain". The Tablet. Retrieved 28 August 2019.

- ↑ "Bevis Marks gets £2.8m in Lottery money towards conservation project". The Jewish Chronicle. 26 June 2019. Retrieved 28 August 2019.

- ↑ "Heritage Lottery Fund £1.7m award". The US. 17 January 2018. Retrieved 28 August 2019.

- ↑ Burn, Chris (6 September 2018). "Yorkshire Holocaust survivors open £1m education centre to teach next generation about horrors they endured". Yorkshire Post. Retrieved 28 August 2019.

- ↑ Frot, Mathilde (26 March 2019). "National Holocaust Centre and Museum secures £97,100 grant". Jewish News. Retrieved 28 August 2019.

- ↑ Morrison, Jonathan; Burgess, Kaya (3 September 2019). "Imperial War Museum's £30m plan to show how Holocaust shaped war". The Times. Retrieved 3 September 2019.

- ↑ Burns, Judith (30 August 2019). "Campus anti-Semitism must be stamped out, says universities minister". BBC News. Retrieved 17 May 2019.

- ↑ Jenrick, Robert; Skidmore, Chris (15 September 2019). "Communities Secretary commits funding to tackle online hate". 15 September 2019. Retrieved 15 September 2019.

- ↑ Harpin, Lee (15 September 2019). "Communities minister Robert Jenrick vows to tackle parts of local Government 'corrupted' by antisemitism". The Jewish Chronicle. Retrieved 15 September 2019.

- ↑ Boyd, Jonathan (6 February 2019). "Leaving or remaining? We're still thinking about it". The Jewish Chronicle. Retrieved 28 August 2019.

- ↑ "Almost 70% of British Jews are hiding their identity and almost half have considered leaving Britain since 7th October, new CAA polling shows". Campaign Against Antisemitism. Retrieved 19 December 2023.

- ↑ "Nearly half of UK Jews considered leaving due to antisemitism - poll". The Jerusalem Post | JPost.com. 18 December 2023. Retrieved 18 December 2023.

Bibliography

- Billig, Michael (1978). Fascists: A Social Psychological View of the National Front. London: Academic Press. ISBN 978-0150040040.

- Cardaun, Sarah K. (2015). Countering Contemporary Antisemitism in Britain. BRILL. p. 37. ISBN 978-9004300880.

- Donaldson, Kitty (27 September 2017). "New Anti-Semitism Scandal Prompts U.K. Labour to Tighten Rules". Bloomberg. Retrieved 25 November 2017.

- Elgot, Jessica (26 September 2017). "Labour to adopt new antisemitism rules after conference row". The Guardian. Retrieved 25 November 2017.

- Filby, Liza (2005). "Religion and Belief". In Thane, Pat (ed.). Unequal Britain: Equalities in Britain Since 1945. Bloomsbury. p. 56. ISBN 978-1847062987.

- Goodwin, Matthew (2011). New British Fascism: Rise of the British National Party. Routledge. ISBN 978-0415465014.

- Judd, Denis; Surridge, Keith (2013). The Boer War: A History. I.B.Tauris. ISBN 978-0-857-73316-0.

- Lavezzo, Kathy (2016). The Accommodated Jew: English Antisemitism from Bede to Milton. Cornell University Press. p. 392. ISBN 978-1-5017-0315-7.

- Mundill, Robin R. (2010), The King's Jews, London: Continuum, ISBN 978-1847251862, LCCN 2010282921, OCLC 466343661, OL 24816680M

- Nachmani, Amikam (2017). Haunted Presents: Europeans, Muslim Immigrants and the Onus of European-Jewish Histories. Oxford University Press. p. 88. ISBN 978-1784993078.

- Seymour, Richard (6 April 2018a). "Labour's Antisemitism Affair". Jacobin. Retrieved 28 May 2018.

- Stacey, Robert C. (2003). "The English Jews Under Henry III: Historical, Literary and Archaeological Perspectives". In Skinner, Patricia (ed.). Jews in Medieval Britain. Woodbridge, UK: Boydell Press. pp. 41–54. ISBN 978-1-84383-733-6.

- Staetsky, L. Daniel (12 September 2017). Antisemitism in contemporary Great Britain: A study of attitudes towards Jews and Israel (PDF). Institute for Jewish Policy Research. pp. 1–82.

- Toczek, Nick (2016). Haters, Baiters and Would-be Dictators: Anti-Semitism and the UK Far Right (Abingdon: Routledge).

- Weaver, Matthew; Elgot, Jessica (26 September 2017). "Labour fringe speaker's Holocaust remarks spark new antisemitism row". The Guardian. Retrieved 25 November 2017.

- Wheatcroft, Geoffrey (28 June 2018). "Bad Company". New York Review of Books.

- Wistrich, Robert S. (2012). From Ambivalence to Betrayal: The Left, the Jews, and Israel. University of Nebraska Press/Vidal Sassoon International Center for the Study of Antisemitism. ISBN 978-0-803-24083-4.

Further reading

External links

![]() Media related to Antisemitism in the United Kingdom at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Antisemitism in the United Kingdom at Wikimedia Commons