Richard Wagner | |

|---|---|

Wagner in 1871 | |

| Born | 22 May 1813 |

| Died | 13 February 1883 (aged 69) |

| Works | List of compositions |

| Signature | |

| |

Wilhelm Richard Wagner (/ˈvɑːɡnər/ VAHG-nər;[1][2] German: [ˈʁɪçaʁt ˈvaːɡnɐ] ⓘ; 22 May 1813 – 13 February 1883) was a German composer, theatre director, polemicist, and conductor who is chiefly known for his operas (or, as some of his mature works were later known, "music dramas"). Unlike most opera composers, Wagner wrote both the libretto and the music for each of his stage works. Initially establishing his reputation as a composer of works in the romantic vein of Carl Maria von Weber and Giacomo Meyerbeer, Wagner revolutionised opera through his concept of the Gesamtkunstwerk ("total work of art"), by which he sought to synthesise the poetic, visual, musical and dramatic arts, with music subsidiary to drama. He described this vision in a series of essays published between 1849 and 1852. Wagner realised these ideas most fully in the first half of the four-opera cycle Der Ring des Nibelungen (The Ring of the Nibelung).

His compositions, particularly those of his later period, are notable for their complex textures, rich harmonies and orchestration, and the elaborate use of leitmotifs—musical phrases associated with individual characters, places, ideas, or plot elements. His advances in musical language, such as extreme chromaticism and quickly shifting tonal centres, greatly influenced the development of classical music. His Tristan und Isolde is sometimes described as marking the start of modern music.

Wagner had his own opera house built, the Bayreuth Festspielhaus, which embodied many novel design features. The Ring and Parsifal were premiered here and his most important stage works continue to be performed at the annual Bayreuth Festival, which was galvanized by the efforts of his wife Cosima Wagner and the family's descendants. His thoughts on the relative contributions of music and drama in opera were to change again, and he reintroduced some traditional forms into his last few stage works, including Die Meistersinger von Nürnberg (The Mastersingers of Nuremberg).

Until his final years, Wagner's life was characterised by political exile, turbulent love affairs, poverty and repeated flight from his creditors. His controversial writings on music, drama and politics have attracted extensive comment – particularly since the late 20th century, as they express antisemitic sentiments. The effect of his ideas can be traced in many of the arts throughout the 20th century; his influence spread beyond composition into conducting, philosophy, literature, the visual arts and theatre.

Biography

Early years

Richard Wagner was born on 22 May 1813 to an ethnic German family in Leipzig, then part of the Confederation of the Rhine. His family lived at No 3, the Brühl (The House of the Red and White Lions) in Leipzig's Jewish quarter.[n 1] He was baptized at St. Thomas Church. He was the ninth child of Carl Friedrich Wagner, who was a clerk in the Leipzig police service, and his wife, Johanna Rosine (née Paetz), the daughter of a baker.[3][4][n 2] Wagner's father Carl died of typhoid fever six months after Richard's birth. Afterwards, his mother Johanna lived with Carl's friend, the actor and playwright Ludwig Geyer.[6] In August 1814 Johanna and Geyer probably married—although no documentation of this has been found in the Leipzig church registers.[7] She and her family moved to Geyer's residence in Dresden. Until he was fourteen, Wagner was known as Wilhelm Richard Geyer. He almost certainly thought that Geyer was his biological father.[8]

Geyer's love of the theatre came to be shared by his stepson, and Wagner took part in his performances. In his autobiography Mein Leben Wagner recalled once playing the part of an angel.[9] In late 1820, Wagner was enrolled at Pastor Wetzel's school at Possendorf, near Dresden, where he received some piano instruction from his Latin teacher.[10] He struggled to play a proper scale at the keyboard and preferred playing theatre overtures by ear. Following Geyer's death in 1821, Richard was sent to the Kreuzschule, the boarding school of the Dresdner Kreuzchor, at the expense of Geyer's brother.[11] At the age of nine he was hugely impressed by the Gothic elements of Carl Maria von Weber's opera Der Freischütz, which he saw Weber conduct.[12] At this period Wagner entertained ambitions as a playwright. His first creative effort, listed in the Wagner-Werk-Verzeichnis (the standard listing of Wagner's works) as WWV 1, was a tragedy called Leubald. Begun when he was in school in 1826, the play was strongly influenced by Shakespeare and Goethe. Wagner was determined to set it to music and persuaded his family to allow him music lessons.[13][n 3]

By 1827, the family had returned to Leipzig. Wagner's first lessons in harmony were taken during 1828–1831 with Christian Gottlieb Müller.[14] In January 1828 he first heard Beethoven's 7th Symphony and then, in March, the same composer's 9th Symphony (both at the Gewandhaus). Beethoven became a major inspiration, and Wagner wrote a piano transcription of the 9th Symphony.[15] He was also greatly impressed by a performance of Mozart's Requiem.[16] Wagner's early piano sonatas and his first attempts at orchestral overtures date from this period.[17]

In 1829 he saw a performance by dramatic soprano Wilhelmine Schröder-Devrient, and she became his ideal of the fusion of drama and music in opera. In Mein Leben, Wagner wrote, "When I look back across my entire life I find no event to place beside this in the impression it produced on me," and claimed that the "profoundly human and ecstatic performance of this incomparable artist" kindled in him an "almost demonic fire."[18][n 4]

In 1831, Wagner enrolled at the Leipzig University, where he became a member of the Saxon student fraternity.[20] He took composition lessons with the Thomaskantor Theodor Weinlig.[21] Weinlig was so impressed with Wagner's musical ability that he refused any payment for his lessons. He arranged for his pupil's Piano Sonata in B-flat major (which was consequently dedicated to him) to be published as Wagner's Op. 1. A year later, Wagner composed his Symphony in C major, a Beethovenesque work performed in Prague in 1832[22] and at the Leipzig Gewandhaus in 1833.[23] He then began to work on an opera, Die Hochzeit (The Wedding), which he never completed.[24]

Early career and marriage (1833–1842)

In 1833, Wagner's brother Albert managed to obtain for him a position as choirmaster at the theatre in Würzburg.[25] In the same year, at the age of 20, Wagner composed his first complete opera, Die Feen (The Fairies). This work, which imitated the style of Weber, went unproduced until half a century later, when it was premiered in Munich shortly after the composer's death in 1883.[26]

Having returned to Leipzig in 1834, Wagner held a brief appointment as musical director at the opera house in Magdeburg[27] during which he wrote Das Liebesverbot (The Ban on Love), based on Shakespeare's Measure for Measure. This was staged at Magdeburg in 1836 but closed before the second performance; this, together with the financial collapse of the theatre company employing him, left the composer in bankruptcy.[28][29] Wagner had fallen for one of the leading ladies at Magdeburg, the actress Christine Wilhelmine "Minna" Planer[30] and after the disaster of Das Liebesverbot he followed her to Königsberg, where she helped him to get an engagement at the theatre.[31] The two married in Tragheim Church on 24 November 1836.[32] In May 1837, Minna left Wagner for another man,[33] and this was but only the first débâcle of a tempestuous marriage. In June 1837, Wagner moved to Riga (then in the Russian Empire), where he became music director of the local opera;[34] having in this capacity engaged Minna's sister Amalie (also a singer) for the theatre, he presently resumed relations with Minna during 1838.[35]

By 1839, the couple had amassed such large debts that they fled Riga on the run from creditors.[36] Debts would plague Wagner for most of his life.[37] Initially they took a stormy sea passage to London,[38] from which Wagner drew the inspiration for his opera Der fliegende Holländer (The Flying Dutchman), with a plot based on a sketch by Heinrich Heine.[39] The Wagners settled in Paris in September 1839[30] and stayed there until 1842. Wagner made a scant living by writing articles and short novelettes such as A pilgrimage to Beethoven, which sketched his growing concept of "music drama", and An end in Paris, where he depicts his own miseries as a German musician in the French metropolis.[40] He also provided arrangements of operas by other composers, largely on behalf of the Schlesinger publishing house. During this stay he completed his third and fourth operas Rienzi and Der fliegende Holländer.[40]

Dresden (1842–1849)

Wagner had completed Rienzi in 1840. With the strong support of Giacomo Meyerbeer,[41] it was accepted for performance by the Dresden Court Theatre (Hofoper) in the Kingdom of Saxony and in 1842, Wagner moved to Dresden. His relief at returning to Germany was recorded in his "Autobiographic Sketch" of 1842, where he wrote that, en route from Paris, "For the first time I saw the Rhine—with hot tears in my eyes, I, poor artist, swore eternal fidelity to my German fatherland."[42] Rienzi was staged to considerable acclaim on 20 October.[43]

Wagner lived in Dresden for the next six years, eventually being appointed the Royal Saxon Court Conductor.[44] During this period, he staged there Der fliegende Holländer (2 January 1843)[45] and Tannhäuser (19 October 1845),[46] the first two of his three middle-period operas. Wagner also mixed with artistic circles in Dresden, including the composer Ferdinand Hiller and the architect Gottfried Semper.[47][48]

Wagner's involvement in left-wing politics abruptly ended his welcome in Dresden. Wagner was active among socialist German nationalists there, regularly receiving such guests as the conductor and radical editor August Röckel and the Russian anarchist Mikhail Bakunin.[49] He was also influenced by the ideas of Pierre-Joseph Proudhon and Ludwig Feuerbach.[50] Widespread discontent came to a head in 1849, when the unsuccessful May Uprising in Dresden broke out, in which Wagner played a minor supporting role. Warrants were issued for the revolutionaries' arrest. Wagner had to flee, first visiting Paris and then settling in Zürich[51][n 5] where he at first took refuge with a friend, Alexander Müller.[52]

In exile: Switzerland (1849–1858)

Wagner was to spend the next twelve years in exile from Germany. He had completed Lohengrin, the last of his middle-period operas, before the Dresden uprising, and now wrote desperately to his friend Franz Liszt to have it staged in his absence. Liszt conducted the premiere in Weimar in August 1850.[53]

Nevertheless, Wagner was in grim personal straits, isolated from the German musical world and without any regular income. In 1850, Julie, the wife of his friend Karl Ritter, began to pay him a small pension which she maintained until 1859. With help from her friend Jessie Laussot, this was to have been augmented to an annual sum of 3,000 thalers per year, but the plan was abandoned when Wagner began an affair with Mme. Laussot. Wagner even plotted an elopement with her in 1850, which her husband prevented.[54][55] Meanwhile, Wagner's wife Minna, who had disliked the operas he had written after Rienzi, was falling into a deepening depression. Wagner fell victim to ill health, according to Ernest Newman "largely a matter of overwrought nerves", which made it difficult for him to continue writing.[56][n 6]

Wagner's primary published output during his first years in Zürich was a set of essays. In "The Artwork of the Future" (1849), he described a vision of opera as Gesamtkunstwerk (total work of art), in which music, song, dance, poetry, visual arts and stagecraft were unified. "Judaism in Music" (1850)[n 7] was the first of Wagner's writings to feature antisemitic views.[58] In this polemic Wagner argued, frequently using traditional antisemitic abuse, that Jews had no connection to the German spirit, and were thus capable of producing only shallow and artificial music. According to him, they composed music to achieve popularity and, thereby, financial success, as opposed to creating genuine works of art.[59]

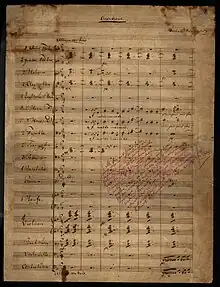

In "Opera and Drama" (1851), Wagner described the aesthetics of music drama that he was using to create the Ring cycle. Before leaving Dresden, Wagner had drafted a scenario that eventually became Der Ring des Nibelungen. He initially wrote the libretto for a single opera, Siegfrieds Tod (Siegfried's Death), in 1848. After arriving in Zürich, he expanded the story with Der junge Siegfried (Young Siegfried), which explored the hero's background. He completed the text of the cycle by writing the libretti for Die Walküre (The Valkyrie) and Das Rheingold (The Rhine Gold) and revising the other libretti to conform to his new concept, completing them in 1852.[60] The concept of opera expressed in "Opera and Drama" and in other essays effectively renounced all the operas he had previously written through Lohengrin. Partly in an attempt to explain his change of views, Wagner published in 1851 the autobiographical "A Communication to My Friends".[61] This included his first public announcement of what was to become the Ring cycle:

I shall never write an Opera more. As I have no wish to invent an arbitrary title for my works, I will call them Dramas ...

I propose to produce my myth in three complete dramas, preceded by a lengthy Prelude (Vorspiel)....

At a specially-appointed Festival, I propose, some future time, to produce those three Dramas with their Prelude, in the course of three days and a fore-evening [emphasis in original].[62]

Wagner began composing the music for Das Rheingold between November 1853 and September 1854, following it immediately with Die Walküre (written between June 1854 and March 1856).[63] He began work on the third Ring drama, which he now called simply Siegfried, probably in September 1856, but by June 1857 he had completed only the first two acts. He decided to put the work aside to concentrate on a new idea: Tristan und Isolde,[64] based on the Arthurian love story Tristan and Iseult.

One source of inspiration for Tristan und Isolde was the philosophy of Arthur Schopenhauer, notably his The World as Will and Representation, to which Wagner had been introduced in 1854 by his poet friend Georg Herwegh. Wagner later called this the most important event of his life.[65][n 8] His personal circumstances certainly made him an easy convert to what he understood to be Schopenhauer's philosophy, sometimes categorized as "philosophical pessimism". He remained an adherent of Schopenhauer for the rest of his life.[66]

One of Schopenhauer's doctrines was that music held a supreme role in the arts as a direct expression of the world's essence, namely, blind, impulsive will.[67] This doctrine contradicted Wagner's view, expressed in "Opera and Drama", that the music in opera had to be subservient to the drama. Wagner scholars have argued that Schopenhauer's influence caused Wagner to assign a more commanding role to music in his later operas, including the latter half of the Ring cycle, which he had yet to compose.[68][n 9] Aspects of Schopenhauerian doctrine found their way into Wagner's subsequent libretti.[n 10]

A second source of inspiration was Wagner's infatuation with the poet-writer Mathilde Wesendonck, the wife of the silk merchant Otto Wesendonck. Wagner met the Wesendoncks, who were both great admirers of his music, in Zürich in 1852. From May 1853 onwards Wesendonck made several loans to Wagner to finance his household expenses in Zürich,[71] and in 1857 placed a cottage on his estate at Wagner's disposal,[72][73] which became known as the Asyl ("asylum" or "place of rest"). During this period, Wagner's growing passion for his patron's wife inspired him to put aside work on the Ring cycle (which was not resumed for the next twelve years) and begin work on Tristan.[74] While planning the opera, Wagner composed the Wesendonck Lieder, five songs for voice and piano, setting poems by Mathilde. Two of these settings are explicitly subtitled by Wagner as "studies for Tristan und Isolde".[75]

Among the conducting engagements that Wagner undertook for revenue during this period, he gave several concerts in 1855 with the Philharmonic Society of London, including one before Queen Victoria.[76] The Queen enjoyed his Tannhäuser overture and spoke with Wagner after the concert, writing in her diary that Wagner was "short, very quiet, wears spectacles & has a very finely-developed forehead, a hooked nose & projecting chin."[77]

In exile: Venice and Paris (1858–1862)

Wagner's uneasy affair with Mathilde collapsed in 1858, when Minna intercepted a letter to Mathilde from him.[78] After the resulting confrontation with Minna, Wagner left Zürich alone, bound for Venice, where he rented an apartment in the Palazzo Giustinian, while Minna returned to Germany.[79] Wagner's attitude to Minna had changed; the editor of his correspondence with her, John Burk, has said that she was to him "an invalid, to be treated with kindness and consideration, but, except at a distance, [was] a menace to his peace of mind."[80] Wagner continued his correspondence with Mathilde and his friendship with her husband Otto, who maintained his financial support of the composer. In an 1859 letter to Mathilde, Wagner wrote, half-satirically, of Tristan: "Child! This Tristan is turning into something terrible. This final act!!!—I fear the opera will be banned ... only mediocre performances can save me! Perfectly good ones will be bound to drive people mad."[81]

In November 1859, Wagner once again moved to Paris to oversee production of a new revision of Tannhäuser, staged thanks to the efforts of Princess Pauline von Metternich, whose husband was the Austrian ambassador in Paris. The performances of the Paris Tannhäuser in 1861 were a notable fiasco. This was partly a consequence of the conservative tastes of the Jockey Club, which organised demonstrations in the theatre to protest at the presentation of the ballet feature in act 1 (instead of its traditional location in the second act); but the opportunity was also exploited by those who wanted to use the occasion as a veiled political protest against the pro-Austrian policies of Napoleon III.[82] It was during this visit that Wagner met the French poet Charles Baudelaire, who wrote an appreciative brochure, "Richard Wagner et Tannhäuser à Paris".[83] The opera was withdrawn after the third performance and Wagner left Paris soon after.[84] He had sought a reconciliation with Minna during this Paris visit, and although she joined him there, the reunion was not successful and they again parted from each other when Wagner left.[85]

Return and resurgence (1862–1871)

The political ban that had been placed on Wagner in Germany after he had fled Dresden was fully lifted in 1862. The composer settled in Biebrich, on the Rhine near Wiesbaden in Hesse.[86] Here Minna visited him for the last time: they parted irrevocably,[87] though Wagner continued to give financial support to her while she lived in Dresden until her death in 1866.[88]

In Biebrich, Wagner, at last, began work on Die Meistersinger von Nürnberg, his only mature comedy. Wagner wrote a first draft of the libretto in 1845,[89] and he had resolved to develop it during a visit he had made to Venice with the Wesendoncks in 1860, where he was inspired by Titian's painting The Assumption of the Virgin.[90] Throughout this period (1861–1864) Wagner sought to have Tristan und Isolde produced in Vienna.[91] Despite many rehearsals, the opera remained unperformed, and gained a reputation as being "impossible" to sing, which added to Wagner's financial problems.[92]

Wagner's fortunes took a dramatic upturn in 1864, when King Ludwig II succeeded to the throne of Bavaria at the age of 18. The young king, an ardent admirer of Wagner's operas, had the composer brought to Munich.[93] The King, who was homosexual, expressed in his correspondence a passionate personal adoration for the composer,[n 11] and Wagner in his responses had no scruples about feigning reciprocal feelings.[95][96][n 12] Ludwig settled Wagner's considerable debts,[98] and proposed to stage Tristan, Die Meistersinger, the Ring, and the other operas Wagner planned.[99] Wagner also began to dictate his autobiography, Mein Leben, at the King's request.[100] Wagner noted that his rescue by Ludwig coincided with news of the death of his earlier mentor (but later supposed enemy) Giacomo Meyerbeer, and regretted that "this operatic master, who had done me so much harm, should not have lived to see this day."[101]

After grave difficulties in rehearsal, Tristan und Isolde premiered at the National Theatre Munich on 10 June 1865, the first Wagner opera premiere in almost 15 years. (The premiere had been scheduled for 15 May, but was delayed by bailiffs acting for Wagner's creditors,[102] and also because the Isolde, Malvina Schnorr von Carolsfeld, was hoarse and needed time to recover.) The conductor of this premiere was Hans von Bülow, whose wife, Cosima, had given birth in April that year to a daughter, named Isolde, a child not of Bülow but of Wagner.[103]

Cosima was 24 years younger than Wagner and was herself illegitimate, the daughter of the Countess Marie d'Agoult, who had left her husband for Franz Liszt.[104] Liszt initially disapproved of his daughter's involvement with Wagner, though nevertheless, the two men were friends.[105] The indiscreet affair scandalised Munich, and Wagner also fell into disfavour with many leading members of the court, who were suspicious of his influence on the King.[106] In December 1865, Ludwig was finally forced to ask the composer to leave Munich.[107] He apparently also toyed with the idea of abdicating to follow his hero into exile, but Wagner quickly dissuaded him.[108]

.jpg.webp)

Ludwig installed Wagner at the Villa Tribschen, beside Switzerland's Lake Lucerne.[109] Die Meistersinger was completed at Tribschen in 1867, and premiered in Munich on 21 June the following year.[89] At Ludwig's insistence, "special previews" of the first two works of the Ring, Das Rheingold and Die Walküre, were performed at Munich in 1869 and 1870,[110] but Wagner retained his dream, first expressed in "A Communication to My Friends", to present the first complete cycle at a special festival with a new, dedicated, opera house.[111]

Minna died of a heart attack on 25 January 1866 in Dresden. Wagner did not attend the funeral.[112][n 13] Following Minna's death Cosima wrote to Hans von Bülow several times asking him to grant her a divorce, but Bülow refused to concede this. He consented only after she had two more children with Wagner; another daughter, named Eva, after the heroine of Meistersinger, and a son Siegfried, named after the hero of the Ring. The divorce was finally sanctioned, after delays in the legal process, by a Berlin court on 18 July 1870.[114] Richard and Cosima's wedding took place on 25 August 1870.[115] On Christmas Day of that year, Wagner arranged a surprise performance (its premiere) of the Siegfried Idyll for Cosima's birthday.[116][n 14] The marriage to Cosima lasted to the end of Wagner's life.

Wagner, settled into his new-found domesticity, turned his energies towards completing the Ring cycle. He had not abandoned polemics: he republished his 1850 pamphlet "Judaism in Music", originally issued under a pseudonym, under his own name in 1869. He extended the introduction, and wrote a lengthy additional final section. The publication led to several public protests at early performances of Die Meistersinger in Vienna and Mannheim.[117]

Bayreuth (1871–1876)

In 1871, Wagner decided to move to Bayreuth, which was to be the location of his new opera house.[118] The town council donated a large plot of land—the "Green Hill"—as a site for the theatre. The Wagners moved to the town the following year, and the foundation stone for the Bayreuth Festspielhaus ("Festival Theatre") was laid. Wagner initially announced the first Bayreuth Festival, at which for the first time the Ring cycle would be presented complete, for 1873,[119] but since Ludwig had declined to finance the project, the start of building was delayed and the proposed date for the festival was deferred. To raise funds for the construction, "Wagner societies" were formed in several cities,[120] and Wagner began touring Germany conducting concerts.[121] By the spring of 1873, only a third of the required funds had been raised; further pleas to Ludwig were initially ignored, but early in 1874, with the project on the verge of collapse, the King relented and provided a loan.[122][123][n 15] The full building programme included the family home, "Wahnfried", into which Wagner, with Cosima and the children, moved from their temporary accommodation on 18 April 1874.[125][126] The theatre was completed in 1875, and the festival was scheduled for the following year. Commenting on the struggle to finish the building, Wagner remarked to Cosima: "Each stone is red with my blood and yours".[127]

For the design of the Festspielhaus, Wagner appropriated some of the ideas of his former colleague, Gottfried Semper, which he had previously solicited for a proposed new opera house in Munich.[119] Wagner was responsible for several theatrical innovations at Bayreuth; these include darkening the auditorium during performances, and placing the orchestra in a pit out of view of the audience.[128]

The Festspielhaus finally opened on 13 August 1876 with Das Rheingold, at last taking its place as the first evening of the complete Ring cycle; the 1876 Bayreuth Festival therefore saw the premiere of the complete cycle, performed as a sequence as the composer had intended.[129] The 1876 Festival consisted of three full Ring cycles (under the baton of Hans Richter).[130] At the end, critical reactions ranged between that of the Norwegian composer Edvard Grieg, who thought the work "divinely composed", and that of the French newspaper Le Figaro, which called the music "the dream of a lunatic".[131] The disillusioned included Wagner's friend and disciple Friedrich Nietzsche, who, having published his eulogistic essay "Richard Wagner in Bayreuth" before the festival as part of his Untimely Meditations, was bitterly disappointed by what he saw as Wagner's pandering to increasingly exclusivist German nationalism; his breach with Wagner began at this time.[132] The festival firmly established Wagner as an artist of European, and indeed world, importance: attendees included Kaiser Wilhelm I, the Emperor Pedro II of Brazil, Anton Bruckner, Camille Saint-Saëns and Pyotr Ilyich Tchaikovsky.[133]

Wagner was far from satisfied with the Festival; Cosima recorded that months later, his attitude towards the productions was "Never again, never again!"[134] Moreover, the festival finished with a deficit of about 150,000 marks.[135] The expenses of Bayreuth and of Wahnfried meant that Wagner still sought further sources of income by conducting or taking on commissions such as the Centennial March for America, for which he received $5000.[136][137]

Last years (1876–1883)

Following the first Bayreuth Festival, Wagner began work on Parsifal, his final opera. The composition took four years, much of which Wagner spent in Italy for health reasons.[138] From 1876 to 1878 Wagner also embarked on the last of his documented emotional liaisons, this time with Judith Gautier, whom he had met at the 1876 Festival.[139] Wagner was also much troubled by problems of financing Parsifal, and by the prospect of the work being performed by other theatres than Bayreuth. He was once again assisted by the liberality of King Ludwig, but was still forced by his personal financial situation in 1877 to sell the rights of several of his unpublished works (including the Siegfried Idyll) to the publisher Schott.[140]

Wagner wrote several articles in his later years, often on political topics, and often reactionary in tone, repudiating some of his earlier, more liberal, views. These include "Religion and Art" (1880) and "Heroism and Christianity" (1881), which were printed in the journal Bayreuther Blätter, published by his supporter Hans von Wolzogen.[141] Wagner's sudden interest in Christianity at this period, which infuses Parsifal, was contemporary with his increasing alignment with German nationalism, and required on his part, and the part of his associates, "the rewriting of some recent Wagnerian history", so as to represent, for example, the Ring as a work reflecting Christian ideals.[142] Many of these later articles, including "What is German?" (1878, but based on a draft written in the 1860s),[143] repeated Wagner's antisemitic preoccupations.

Wagner completed Parsifal in January 1882, and a second Bayreuth Festival was held for the new opera, which premiered on 26 May.[144] Wagner was by this time extremely ill, having suffered a series of increasingly severe angina attacks.[145] During the sixteenth and final performance of Parsifal on 29 August, he entered the pit unseen during act 3, took the baton from conductor Hermann Levi, and led the performance to its conclusion.[146]

After the festival, the Wagner family journeyed to Venice for the winter. Wagner died of a heart attack at the age of 69 on 13 February 1883 at Ca' Vendramin Calergi, a 16th-century palazzo on the Grand Canal.[147] The legend that the attack was prompted by an argument with Cosima over Wagner's supposedly amorous interest in the singer Carrie Pringle, who had been a Flower-maiden in Parsifal at Bayreuth, is without credible evidence.[148] After a funerary gondola bore Wagner's remains over the Grand Canal, his body was taken to Germany where it was buried in the garden of the Villa Wahnfried in Bayreuth.[149]

Works

Wagner's musical output is listed by the Wagner-Werk-Verzeichnis (WWV) as comprising 113 works, including fragments and projects.[150] The first complete scholarly edition of his musical works in print was commenced in 1970 under the aegis of the Bavarian Academy of Fine Arts and the Akademie der Wissenschaften und der Literatur of Mainz, and is presently under the editorship of Egon Voss. It will consist of 21 volumes (57 books) of music and 10 volumes (13 books) of relevant documents and texts. As at October 2017, three volumes remain to be published. The publisher is Schott Music.[151]

Operas

Wagner's operatic works are his primary artistic legacy. Unlike most opera composers, who generally left the task of writing the libretto (the text and lyrics) to others, Wagner wrote his own libretti, which he referred to as "poems".[152]

From 1849 onwards, he urged a new concept of opera often referred to as "music drama" (although he later rejected this term),[153][n 16] in which all musical, poetic and dramatic elements were to be fused together—the Gesamtkunstwerk. Wagner developed a compositional style in which the importance of the orchestra is equal to that of the singers. The orchestra's dramatic role in the later operas includes the use of leitmotifs, musical phrases that can be interpreted as announcing specific characters, locales, and plot elements; their complex interweaving and evolution illuminate the progression of the drama.[155] These operas are still, despite Wagner's reservations, referred to by many writers[156] as "music dramas".[157]

Early works (to 1842)

Wagner's earliest attempts at opera were often uncompleted. Abandoned works include a pastoral opera based on Goethe's Die Laune des Verliebten (The Infatuated Lover's Caprice), written at the age of 17,[24] Die Hochzeit (The Wedding), on which Wagner worked in 1832,[24] and the singspiel Männerlist größer als Frauenlist (Men are More Cunning than Women, 1837–1838). Die Feen (The Fairies, 1833) was not performed in the composer's lifetime[26] and Das Liebesverbot (The Ban on Love, 1836) was withdrawn after its first performance.[28] Rienzi (1842) was Wagner's first opera to be successfully staged.[158] The compositional style of these early works was conventional—the relatively more sophisticated Rienzi showing the clear influence of Grand Opera à la Spontini and Meyerbeer—and did not exhibit the innovations that would mark Wagner's place in musical history. Later in life, Wagner said that he did not consider these works to be part of his oeuvre;[159] and they have been performed only rarely in the last hundred years, although the overture to Rienzi is an occasional concert-hall piece. Die Feen, Das Liebesverbot, and Rienzi were performed at both Leipzig and Bayreuth in 2013 to mark the composer's bicentenary.[160]

"Romantic operas" (1843–1851)

Wagner's middle stage output began with Der fliegende Holländer (The Flying Dutchman, 1843), followed by Tannhäuser (1845) and Lohengrin (1850). These three operas are sometimes referred to as Wagner's "romantic operas".[161] They reinforced the reputation, among the public in Germany and beyond, that Wagner had begun to establish with Rienzi. Although distancing himself from the style of these operas from 1849 onwards, he nevertheless reworked both Der fliegende Holländer and Tannhäuser on several occasions.[n 17] These three operas are considered to represent a significant developmental stage in Wagner's musical and operatic maturity as regards thematic handling, portrayal of emotions and orchestration.[163] They are the earliest works included in the Bayreuth canon, the mature operas that Cosima staged at the Bayreuth Festival after Wagner's death in accordance with his wishes.[164] All three (including the differing versions of Der fliegende Holländer and Tannhäuser) continue to be regularly performed throughout the world, and have been frequently recorded.[n 18] They were also the operas by which his fame spread during his lifetime.[n 19]

"Music dramas" (1851–1882)

Starting the Ring

Wagner's late dramas are considered his masterpieces. Der Ring des Nibelungen, commonly referred to as the Ring or "Ring cycle", is a set of four operas based loosely on figures and elements of Germanic mythology—particularly from the later Norse mythology—notably the Old Norse Poetic Edda and Volsunga Saga, and the Middle High German Nibelungenlied.[166] Wagner specifically developed the libretti for these operas according to his interpretation of Stabreim, highly alliterative rhyming verse-pairs used in old Germanic poetry.[167] They were also influenced by Wagner's concepts of ancient Greek drama, in which tetralogies were a component of Athenian festivals, and which he had amply discussed in his essay "Oper und Drama".[168]

The first two components of the Ring cycle were Das Rheingold (The Rhinegold), which was completed in 1854, and Die Walküre (The Valkyrie), which was finished in 1856. In Das Rheingold, with its "relentlessly talky 'realism' [and] the absence of lyrical 'numbers'",[169] Wagner came very close to the musical ideals of his 1849–1851 essays. Die Walküre, which contains what is virtually a traditional aria (Siegmund's Winterstürme in the first act), and the quasi-choral appearance of the Valkyries themselves, shows more "operatic" traits, but has been assessed by Barry Millington as "the music drama that most satisfactorily embodies the theoretical principles of 'Oper und Drama'... A thoroughgoing synthesis of poetry and music is achieved without any notable sacrifice in musical expression."[170]

Tristan und Isolde and Die Meistersinger

While composing the opera Siegfried, the third part of the Ring cycle, Wagner interrupted work on it and between 1857 and 1864 wrote the tragic love story Tristan und Isolde and his only mature comedy Die Meistersinger von Nürnberg (The Mastersingers of Nuremberg), two works that are also part of the regular operatic canon.[171]

Tristan is often granted a special place in musical history; many see it as the beginning of the move away from conventional harmony and tonality and consider that it lays the groundwork for the direction of classical music in the 20th century.[89][172][173] Wagner felt that his musico-dramatical theories were most perfectly realised in this work with its use of "the art of transition" between dramatic elements and the balance achieved between vocal and orchestral lines.[174] Completed in 1859, the work was given its first performance in Munich, conducted by Bülow, in June 1865.[175]

Die Meistersinger was originally conceived by Wagner in 1845 as a sort of comic pendant to Tannhäuser.[176] Like Tristan, it was premiered in Munich under the baton of Bülow, on 21 June 1868, and became an immediate success.[177] Millington describes Meistersinger as "a rich, perceptive music drama widely admired for its warm humanity",[178] but its strong German nationalist overtones have led some to cite it as an example of Wagner's reactionary politics and antisemitism.[179]

Completing the Ring

When Wagner returned to writing the music for the last act of Siegfried and for Götterdämmerung (Twilight of the Gods), as the final part of the Ring, his style had changed once more to something more recognisable as "operatic" than the aural world of Rheingold and Walküre, though it was still thoroughly stamped with his own originality as a composer and suffused with leitmotifs.[180] This was in part because the libretti of the four Ring operas had been written in reverse order, so that the book for Götterdämmerung was conceived more "traditionally" than that of Rheingold;[181] still, the self-imposed strictures of the Gesamtkunstwerk had become relaxed. The differences also result from Wagner's development as a composer during the period in which he wrote Tristan, Meistersinger and the Paris version of Tannhäuser.[182] From act 3 of Siegfried onwards, the Ring becomes more chromatic melodically, more complex harmonically and more developmental in its treatment of leitmotifs.[183]

Wagner took 26 years from writing the first draft of a libretto in 1848 until he completed Götterdämmerung in 1874. The Ring takes about 15 hours to perform[184] and is the only undertaking of such size to be regularly presented on the world's stages.

Parsifal

Wagner's final opera, Parsifal (1882), which was his only work written especially for his Bayreuth Festspielhaus and which is described in the score as a "Bühnenweihfestspiel" ("festival play for the consecration of the stage"), has a storyline suggested by elements of the legend of the Holy Grail. It also carries elements of Buddhist renunciation suggested by Wagner's readings of Schopenhauer.[185] Wagner described it to Cosima as his "last card".[186] It remains controversial because of its treatment of Christianity, its eroticism, and its expression, as perceived by some commentators, of German nationalism and antisemitism.[187] Despite the composer's own description of the opera to King Ludwig as "this most Christian of works",[188] Ulrike Kienzle has commented that "Wagner's turn to Christian mythology, upon which the imagery and spiritual contents of Parsifal rest, is idiosyncratic and contradicts Christian dogma in many ways."[189] Musically the opera has been held to represent a continuing development of the composer's style, and Millington describes it as "a diaphanous score of unearthly beauty and refinement".[30]

Non-operatic music

Apart from his operas, Wagner composed relatively few pieces of music. These include a symphony in C major (written at the age of 19), the Faust Overture (the only completed part of an intended symphony on the subject), some concert overtures, and choral and piano pieces.[190] His most commonly performed work that is not an extract from an opera is the Siegfried Idyll for chamber orchestra, which has several motifs in common with the Ring cycle.[191] The Wesendonck Lieder are also often performed, either in the original piano version, or with orchestral accompaniment.[n 20] More rarely performed are the American Centennial March (1876), and Das Liebesmahl der Apostel (The Love Feast of the Apostles), a piece for male choruses and orchestra composed in 1843 for the city of Dresden.[192]

After completing Parsifal, Wagner expressed his intention to turn to the writing of symphonies,[193] and several sketches dating from the late 1870s and early 1880s have been identified as work towards this end.[194] The overtures and certain orchestral passages from Wagner's middle and late-stage operas are commonly played as concert pieces. For most of these, Wagner wrote or rewrote short passages to ensure musical coherence. The "Bridal Chorus" from Lohengrin is frequently played as the bride's processional wedding march in English-speaking countries.[195]

Prose writings

Wagner was an extremely prolific writer, authoring many books, poems, and articles, as well as voluminous correspondence. His writings covered a wide range of topics, including autobiography, politics, philosophy, and detailed analyses of his own operas.

Wagner planned for a collected edition of his publications as early as 1865;[196] he believed that such an edition would help the world understand his intellectual development and artistic aims.[197] The first such edition was published between 1871 and 1883, but was doctored to suppress or alter articles that were an embarrassment to him (e.g. those praising Meyerbeer), or by altering dates on some articles to reinforce Wagner's own account of his progress.[198] Wagner's autobiography Mein Leben was originally published for close friends only in a very small edition (15–18 copies per volume) in four volumes between 1870 and 1880. The first public edition (with many passages suppressed by Cosima) appeared in 1911; the first attempt at a full edition (in German) appeared in 1963.[199]

There have been modern complete or partial editions of Wagner's writings,[200] including a centennial edition in German edited by Dieter Borchmeyer (which, however, omitted the essay "Das Judenthum in der Musik" and Mein Leben).[201] The English translations of Wagner's prose in eight volumes by William Ashton Ellis (1892–1899) are still in print and commonly used, despite their deficiencies.[202] The first complete historical and critical edition of Wagner's prose works was launched in 2013 at the Institute for Music Research at the University of Würzburg; this will result in at least eight volumes of text and several volumes of commentary, totalling over 5,000 pages. It was originally anticipated that the project will be completed by 2030.[203]

A complete edition of Wagner's correspondence, estimated to amount to between 10,000 and 12,000 items, is underway under the supervision of the University of Würzburg. As of January 2021, 25 volumes have appeared, covering the period to 1873.[204]

Influence and legacy

Influence on music

Wagner's later musical style introduced new ideas in harmony, melodic process (leitmotif) and operatic structure. Notably from Tristan und Isolde onwards, he explored the limits of the traditional tonal system, which gave keys and chords their identity, pointing the way to atonality in the 20th century. Some music historians date the beginning of modern classical music to the first notes of Tristan, which include the so-called Tristan chord.[205][206]

Wagner inspired great devotion. For a long period, many composers were inclined to align themselves with or against Wagner's music. Anton Bruckner and Hugo Wolf were greatly indebted to him, as were César Franck, Henri Duparc, Ernest Chausson, Jules Massenet, Richard Strauss, Alexander von Zemlinsky, Hans Pfitzner and many others.[207] Gustav Mahler was devoted to Wagner and his music; aged 15, he sought him out on his 1875 visit to Vienna,[208] became a renowned Wagner conductor,[209] and his compositions were seen by Richard Taruskin as extending Wagner's "maximalization" of "the temporal and the sonorous" in music to the world of the symphony.[210] The harmonic revolutions of Claude Debussy and Arnold Schoenberg (both of whose oeuvres contain examples of tonal and atonal modernism) have often been traced back to Tristan and Parsifal.[211][212] The Italian form of operatic realism known as verismo owed much to the Wagnerian concept of musical form.[213]

Wagner made a major contribution to the principles and practice of conducting. His essay "About Conducting" (1869)[214] advanced Hector Berlioz's technique of conducting and claimed that conducting was a means by which a musical work could be re-interpreted, rather than simply a mechanism for achieving orchestral unison. He exemplified this approach in his own conducting, which was significantly more flexible than the disciplined approach of Felix Mendelssohn; in his view, this also justified practices that would today be frowned upon, such as the rewriting of scores.[215][n 21] Wilhelm Furtwängler felt that Wagner and Bülow, through their interpretative approach, inspired a whole new generation of conductors (including Furtwängler himself).[217]

Among those from the late 20th century and beyond claiming inspiration from Wagner's music are the German band Rammstein,[218] Jim Steinman, who wrote songs for Meat Loaf, Bonnie Tyler, Air Supply, Celine Dion and others,[219] and the electronic composer Klaus Schulze, whose 1975 album Timewind consists of two 30-minute tracks, Bayreuth Return and Wahnfried 1883. Joey DeMaio of the band Manowar has described Wagner as "The father of heavy metal".[220] The Slovenian group Laibach created the 2009 suite VolksWagner, using material from Wagner's operas.[221] Phil Spector's Wall of Sound recording technique was, it has been claimed, heavily influenced by Wagner.[222]

Influence on literature, philosophy and the visual arts

Wagner's influence on literature and philosophy is significant. Millington has commented:

[Wagner's] protean abundance meant that he could inspire the use of literary motif in many a novel employing interior monologue; ... the Symbolists saw him as a mystic hierophant; the Decadents found many a frisson in his work.[223]

Friedrich Nietzsche was a member of Wagner's inner circle during the early 1870s, and his first published work, The Birth of Tragedy, proposed Wagner's music as the Dionysian "rebirth" of European culture in opposition to Apollonian rationalist "decadence". Nietzsche broke with Wagner following the first Bayreuth Festival in 1876, believing that Wagner's final phase represented a pandering to Christian pieties and a surrender to the new German Reich.[224] Nevertheless, in Thus Spoke Zarathustra, Nietzsche alluded to Wagner as the "old sorcerer", a reference to the captivating power of Wagner's music.[225] Nietzsche expressed his displeasure with the later Wagner in The Case of Wagner and Nietzsche contra Wagner.[224]

The poets Charles Baudelaire, Stéphane Mallarmé and Paul Verlaine worshipped Wagner.[226] Édouard Dujardin, whose influential novel Les Lauriers sont coupés is in the form of an interior monologue inspired by Wagnerian music, founded a journal dedicated to Wagner, La Revue Wagnérienne, to which J. K. Huysmans and Téodor de Wyzewa contributed.[227] In a list of major cultural figures influenced by Wagner, Bryan Magee includes D. H. Lawrence, Aubrey Beardsley, Romain Rolland, Gérard de Nerval, Pierre-Auguste Renoir, Rainer Maria Rilke and several others.[228]

In the 20th century, W. H. Auden once called Wagner "perhaps the greatest genius that ever lived",[229] while Thomas Mann[224] and Marcel Proust[230] were heavily influenced by him and discussed Wagner in their novels. He is also discussed in some of the works of James Joyce,[231] as well as W. E. B. Du Bois, who featured Lohengrin in The Souls of Black Folk.[232] Wagnerian themes inhabit T. S. Eliot's The Waste Land, which contains lines from Tristan und Isolde and Götterdämmerung, and Verlaine's poem on Parsifal.[233]

Many of Wagner's concepts, including his speculation about dreams, predated their investigation by Sigmund Freud.[234] Wagner had publicly analysed the Oedipus myth before Freud was born in terms of its psychological significance, insisting that incestuous desires are natural and normal, and perceptively exhibiting the relationship between sexuality and anxiety.[235] Georg Groddeck considered the Ring as the first manual of psychoanalysis.[236]

Influence on cinema

Wagner's concept of the use of leitmotifs and the integrated musical expression which they can enable has influenced many 20th and 21st century film scores. The critic Theodor Adorno has noted that the Wagnerian leitmotif "leads directly to cinema music where the sole function of the leitmotif is to announce heroes or situations so as to allow the audience to orient itself more easily".[237] Film scores citing Wagnerian themes include the Looney Tunes short What's Opera, Doc? and Francis Ford Coppola's Apocalypse Now, which both feature a version of the Ride of the Valkyries;[238] Trevor Jones's soundtrack to John Boorman's film Excalibur;[239] and the 2011 films A Dangerous Method (dir. David Cronenberg) and Melancholia (dir. Lars von Trier).[240] Hans-Jürgen Syberberg's 1977 film Hitler: A Film from Germany's visual style and set design are strongly inspired by Der Ring des Nibelungen, musical excerpts from which are frequently used in the film's soundtrack.[241]

Opponents and supporters

Not all reaction to Wagner was positive. For a time, German musical life divided into two factions, supporters of Wagner and supporters of Johannes Brahms; the latter, with the support of the powerful critic Eduard Hanslick (of whom Beckmesser in Meistersinger is in part a caricature), championed traditional forms and led the conservative front against Wagnerian innovations.[242] They were supported by the conservative leanings of some German music schools, including the conservatories at Leipzig under Ignaz Moscheles and at Cologne under the direction of Ferdinand Hiller.[243] Another Wagner detractor was the French composer Charles-Valentin Alkan, who wrote to Hiller after attending Wagner's Paris concert on 25 January 1860 at which Wagner conducted the overtures to Der fliegende Holländer and Tannhäuser, the preludes to Lohengrin and Tristan und Isolde, and six other extracts from Tannhäuser and Lohengrin: "I had imagined that I was going to meet music of an innovative kind but was astonished to find a pale imitation of Berlioz ... I do not like all the music of Berlioz while appreciating his marvellous understanding of certain instrumental effects ... but here he was imitated and caricatured ... Wagner is not a musician, he is a disease."[244]

Even those who, like Debussy, opposed Wagner ("this old poisoner")[245] could not deny his influence. Indeed, Debussy was one of many composers, including Tchaikovsky, who felt the need to break with Wagner precisely because his influence was so unmistakable and overwhelming. "Golliwogg's Cakewalk" from Debussy's Children's Corner piano suite contains a deliberately tongue-in-cheek quotation from the opening bars of Tristan.[246] Others who proved resistant to Wagner's operas included Gioachino Rossini, who said "Wagner has wonderful moments, and dreadful quarters of an hour."[247] In the 20th century Wagner's music was parodied by Paul Hindemith[n 22] and Hanns Eisler, among others.[248]

Wagner's followers (known as Wagnerians or Wagnerites)[249] have formed many societies dedicated to Wagner's life and work.[250]

Film and stage portrayals

Wagner has been the subject of many biographical films. The earliest was a silent film made by Carl Froelich in 1913 and featured in the title role the composer Giuseppe Becce, who also wrote the score for the film (as Wagner's music, still in copyright, was not available).[251] Other film portrayals of Wagner include: Alan Badel in Magic Fire (1955); Lyndon Brook in Song Without End (1960); Trevor Howard in Ludwig (1972); Paul Nicholas in Lisztomania (1975); and Richard Burton in Wagner (1983).[252]

Jonathan Harvey's opera Wagner Dream (2007) intertwines the events surrounding Wagner's death with the story of Wagner's uncompleted opera outline Die Sieger (The Victors).[253]

Bayreuth Festival

Since Wagner's death, the Bayreuth Festival, which has become an annual event, has been successively directed by his widow, his son Siegfried, the latter's widow Winifred Wagner, their two sons Wieland and Wolfgang Wagner, and, presently, two of the composer's great-granddaughters, Eva Wagner-Pasquier and Katharina Wagner.[254] Since 1973, the festival has been overseen by the Richard-Wagner-Stiftung (Richard Wagner Foundation), the members of which include some of Wagner's descendants.[255]

Views

Wagner's operas, writings, politics, beliefs and unorthodox lifestyle made him a controversial figure during his lifetime.[256] Following his death, debate about his ideas and their interpretation, particularly in Germany during the 20th century, has continued.

Racism and antisemitism

Wagner's hostile writings on Jews, including Jewishness in Music, correspond to some existing trends of thought in Germany during the 19th century.[257] Despite his very public views on this topic, throughout his life Wagner had Jewish friends, colleagues and supporters.[258][259] There have been frequent suggestions that antisemitic stereotypes are represented in Wagner's operas. The characters of Alberich and Mime in the Ring, Sixtus Beckmesser in Die Meistersinger, and Klingsor in Parsifal are sometimes claimed as Jewish representations, though they are not identified as such in the librettos of these operas.[260][n 23] The topic is further complicated by claims, which may have been credited by Wagner, that he himself was of Jewish ancestry, via his supposed father Geyer; however, there is no evidence that Geyer had Jewish ancestors.[261][262]

Some biographers have noted that Wagner in his final years developed an interest in the racialist philosophy of Arthur de Gobineau, notably Gobineau's belief that Western society was doomed because of miscegenation between "superior" and "inferior" races.[263] According to Robert Gutman, this theme is reflected in the opera Parsifal.[264] Other biographers (such as Lucy Beckett) believe that this is not true, as the original drafts of the story date back to 1857 and Wagner had completed the libretto for Parsifal by 1877,[265] but he displayed no significant interest in Gobineau until 1880.[266]

Other interpretations

Wagner's ideas are amenable to socialist interpretations; many of his ideas on art were being formulated at the time of his revolutionary inclinations in the 1840s. Thus, for example, George Bernard Shaw wrote in The Perfect Wagnerite (1883):

[Wagner's] picture of Niblunghome[n 24] under the reign of Alberic is a poetic vision of unregulated industrial capitalism as it was made known in Germany in the middle of the 19th century by Engels's book The Condition of the Working Class in England.[267]

Left-wing interpretations of Wagner also inform the writings of Theodor Adorno among other Wagner critics.[n 25] Walter Benjamin gave Wagner as an example of "bourgeois false consciousness", alienating art from its social context.[268] György Lukács contended that the ideas of the early Wagner represented the ideology of the "true socialists" (wahre Sozialisten), a movement referenced in Karl Marx's Communist Manifesto as belonging to the left wing of German bourgeois radicalism and associated with Feuerbachianism and Karl Theodor Ferdinand Grün,[269] while Anatoly Lunacharsky said about the later Wagner: "The circle is complete. The revolutionary has become a reactionary. The rebellious petty bourgeois now kisses the slipper of the Pope, the keeper of order."[270]

The writer Robert Donington has produced a detailed, if controversial, Jungian interpretation of the Ring cycle, described as "an approach to Wagner by way of his symbols", which, for example, sees the character of the goddess Fricka as part of her husband Wotan's "inner femininity".[271] Millington notes that Jean-Jacques Nattiez has also applied psychoanalytical techniques in an evaluation of Wagner's life and works.[272][273]

Nazi appropriation

Adolf Hitler was an admirer of Wagner's music and saw in his operas an embodiment of his own vision of the German nation; in a 1922 speech he claimed that Wagner's works glorified "the heroic Teutonic nature ... Greatness lies in the heroic."[274] Hitler visited Bayreuth frequently from 1923 onwards and attended the productions at the theatre.[275] There continues to be debate about the extent to which Wagner's views might have influenced Nazi thinking.[n 26] Houston Stewart Chamberlain (1855–1927), who married Wagner's daughter Eva in 1908 but never met Wagner, was the author of The Foundations of the Nineteenth Century, approved by the Nazi movement.[277][n 27] Chamberlain met Hitler several times between 1923 and 1927 in Bayreuth, but cannot credibly be regarded as a conduit of Wagner's own views.[280] The Nazis used those parts of Wagner's thought that were useful for propaganda and ignored or suppressed the rest.[281]

While Bayreuth presented a useful front for Nazi culture, and Wagner's music was used at many Nazi events,[282] the Nazi hierarchy as a whole did not share Hitler's enthusiasm for Wagner's operas and resented attending these lengthy epics at Hitler's insistence.[283] Some Nazi ideologists, most notably Alfred Rosenberg, rejected Parsifal as excessively Christian and pacifist.[284]

Guido Fackler has researched evidence that indicates that it is possible that Wagner's music was used at the Dachau concentration camp in 1933–1934 to "reeducate" political prisoners by exposure to "national music".[285] There has been no evidence to support claims, sometimes made,[286] that his music was played at Nazi death camps during the Second World War, and Pamela Potter has noted that Wagner's music was explicitly off-limits in the camps.[n 28]

Because of the associations of Wagner with antisemitism and Nazism, the performance of his music in the State of Israel had been a source of controversy.[287]

References

Notes

- ↑ On the Brühl as a centre of the Jewish quarter, see e.g. the Leipzig page of the Museum of the Jewish People website, and the Leo Baeck Institute page on the Jewish history of Leipzig, also the "Destroyed German Synagogues" site page on Leipzig, (all accessed 19 April 2020.)

- ↑ Of their children, two (Carl Gustave and Maria Theresia) died as infants. The others were Wagner's brothers Albert and Carl Julius, and his sisters Rosalie, Luise, Clara and Ottilie. Except for Carl Julius becoming a goldsmith, all his siblings developed careers connected with the stage. Wagner also had a younger half-sister, Caecilie, born in 1815 to his mother and her second husband Geyer.[5] See also Wagner family tree.

- ↑ This sketch is referred to alternatively as Leubald und Adelaide.

- ↑ Wagner claimed to have seen Schröder-Devrient in the title role of Fidelio, but it seems more likely that he saw her performance as Romeo in Bellini's I Capuleti e i Montecchi.[19]

- ↑ Röckel and Bakunin failed to escape and endured long terms of imprisonment.

- ↑ Gutman records him as suffering from constipation and shingles.[57]

- ↑ Full English translation in Wagner 1995c

- ↑ Others agree on the profound importance of this work to Wagner – see Magee 2000, pp. 133–34

- ↑ The influence was noted by Nietzsche in his "On the Genealogy of Morality": "[the] fascinating position of Schopenhauer on art ... was apparently the reason Richard Wagner first moved over to Schopenhauer ... That shift was so great that it opened up a complete theoretical contrast between his earlier and his later aesthetic beliefs."[69]

- ↑ For example, the self-renouncing cobbler-poet Hans Sachs in Die Meistersinger von Nürnberg is a "Schopenhauerian" creation; Schopenhauer asserted that goodness and salvation result from renunciation of the world, and turning against and denying one's own will.[70]

- ↑ E.g. "My dearest Beloved!", "My beloved, my most glorious Friend" and "O Holy One, I worship you".[94]

- ↑ Wagner excused himself in 1878, when discussing this correspondence with Cosima, by saying "The tone wasn't good, but I didn't set it."[97]

- ↑ Wagner claimed to be unable to travel to the funeral due to an "inflamed finger".[113]

- ↑ Cosima's birthday was 24 December, but she usually celebrated it on Christmas Day.

- ↑ In 1873, the King awarded Wagner the Bavarian Maximilian Order for Science and Art; Wagner was enraged that, at the same time, the honour had been given also to Brahms.[124]

- ↑ In his 1872 essay "On the Designation 'Music Drama'", he criticises the term "music drama" suggesting instead the phrase "deeds of music made visible".[154]

- ↑ For the reworking of Der fliegende Holländer, see Deathridge 1982, pp. 13, 25; for that of Tannhäuser, see Millington 2001a, pp. 280–282 which further cites Wagner's comment to Cosima three weeks before his death that he "still owes the world Tannhäuser."[162] See also the articles on these operas in Wikipedia.

- ↑ See performance listings by opera in Operabase, and the Wikipedia articles Der fliegende Holländer discography, Tannhäuser discography and Lohengrin discography.

- ↑ For example, Der fliegende Holländer (Dutchman) was first performed in London in 1870 and in the US (Philadelphia) in 1876; Tannhäuser in New York in 1859 and in London in 1876; Lohengrin in New York in 1871 and London in 1875.[165] For detailed performance histories including other countries, see Stanford University Wagner site, under each opera.

- ↑ Normally the orchestration by Felix Mottl is used (score available at IMSLP website), although Wagner arranged one of the songs for chamber orchestra.[75]

- ↑ See for example Wagner's proposals for the rescoring of Beethoven's Ninth Symphony in his essay on that work.[216]

- ↑ See Ouvertüre zum "Fliegenden Holländer", wie sie eine schlechte Kurkapelle morgens um 7 am Brunnen vom Blatt spielt

- ↑ Weiner 1997 gives very detailed allegations of antisemitism in Wagner's music and characterisations.

- ↑ Shaw's anglicization of Nibelheim, the empire of Alberich in the Ring cycle.

- ↑ See Žižek 2009, p. viii: "[In this book] for the first time the Marxist reading of a musical work of art ... was combined with the highest musicological analysis."

- ↑ The claim that Hitler, in his maturity, commented that "it [i.e. his political career] all began" after seeing a performance of Rienzi in his youth, has been disproved.[276]

- ↑ The book is described by Roger Allen as "a toxic mix of world history and racially inspired anthropology".[278] Chamberlain is described by Michael D. Biddiss, in the Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, as a "racialist writer".[279]

- ↑ See e.g. John (2004) for a detailed essay on music in the Nazi death camps, which nowhere mentions Wagner. See also Potter (2008), p. 244: "We know from testimonies that concentration camp orchestras played [all sorts of] music ... but that Wagner was explicitly off-limits. However, after the war, unsubstantiated claims that Wagner's music accompanied Jews to their death took on momentum."

Citations

- ↑ Jones, Daniel (2011). Roach, Peter; Setter, Jane; Esling, John (eds.). Cambridge English Pronouncing Dictionary (18th ed.). Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-15255-6.

- ↑ Wells, John C. (2008). Longman Pronunciation Dictionary (3rd ed.). Longman. ISBN 978-1-4058-8118-0.

- ↑ Wagner 1992, p. 3.

- ↑ Newman 1976, I, p. 12.

- ↑ Millington 2001a, p. 97.

- ↑ Newman 1976, I, p. 6.

- ↑ Gutman 1990, pp. 7 and n.

- ↑ Newman 1976, I, p. 9.

- ↑ Wagner 1992, p. 5.

- ↑ Newman 1976, I, pp. 32–33.

- ↑ Newman 1976, I, pp. 45–55.

- ↑ Gutman 1990, p. 78.

- ↑ Wagner 1992, pp. 25–27.

- ↑ Newman 1976, I, pp. 63, 71.

- ↑ Wagner 1992, pp. 35–36.

- ↑ Newman 1976, I, p. 62.

- ↑ Newman 1976, I, pp. 76–77.

- ↑ Wagner 1992, p. 37.

- ↑ Millington 2001a, p. 133.

- ↑ Wagner 1992, p. 44.

- ↑ Newman 1976, I, pp. 85–86.

- ↑ Millington 2001a, p. 309.

- ↑ Newman 1976, I, p. 95.

- 1 2 3 Millington 2001a, p. 321.

- ↑ Newman 1976, I, p. 98.

- 1 2 Millington 2001a, pp. 271–273.

- ↑ Newman 1976, I, p. 173.

- 1 2 Millington 2001a, pp. 273–274.

- ↑ Gutman 1990, p. 52.

- 1 2 3 Millington 2002b.

- ↑ Newman 1976, I, p. 212.

- ↑ Newman 1976, I, p. 214.

- ↑ Newman 1976, I, p. 217.

- ↑ Newman 1976, I, pp. 226–227.

- ↑ Newman 1976, I, pp. 229–231.

- ↑ Newman 1976, I, pp. 242–243.

- ↑ Millington 2001a, pp. 116–118.

- ↑ Newman 1976, I, pp. 249–250.

- ↑ Millington 2001a, p. 277.

- 1 2 Newman 1976, I, pp. 268–324.

- ↑ Newman 1976, I, p. 316.

- ↑ Wagner 1994c, p. 19.

- ↑ Millington 2001a, p. 274.

- ↑ Newman 1976, I, pp. 325–509.

- ↑ Millington 2001a, p. 276.

- ↑ Millington 2001a, p. 279.

- ↑ Millington 2001a, p. 31.

- ↑ Conway 2012, pp. 192–193.

- ↑ Gutman 1990, p. 118.

- ↑ Millington 2001a, pp. 140–144.

- ↑ Wagner 1992, pp. 417–420.

- ↑ Wagner, Richard (1911). Family Letters of Richard Wagner. Translated by Elli, William Ashton. London: Macmillan. p. 154. ISBN 978-0-8443-0014-6.

- ↑ Wagner 1987, p. 199. Letter from Richard Wagner to Franz Liszt, 21 April 1850. See also Millington 2001a, pp. 282, 285

- ↑ Millington 2001a, pp. 27, 30.

- ↑ Newman 1976, II, pp. 133–56, 247–48, 404–05.

- ↑ Newman 1976, II, pp. 137–38.

- ↑ Gutman 1990, p. 142.

- ↑ Conway 2012, pp. 197–98.

- ↑ Conway 2012, pp. 261–63.

- ↑ Millington 2001a, p. 297.

- ↑ See Treadwell 2008, pp. 182–90

- ↑ Wagner 1994c, 391 and n.

- ↑ Millington 2001a, pp. 289, 292.

- ↑ Millington 2001a, pp. 289, 294, 300.

- ↑ Wagner 1992, pp. 508–510.

- ↑ See e.g. Magee 2000, pp. 276–78

- ↑ Magee 1988, pp. 77–78.

- ↑ See e.g. Dahlhaus 1979

- ↑ Nietzsche 2009, III, p. 5..

- ↑ See Magee 2000, pp. 251–53

- ↑ Newman 1976, II, pp. 415–18, 516–18.

- ↑ Gutman 1990, pp. 168–69.

- ↑ Newman 1976, II, pp. 508–09.

- ↑ Millington 2001b.

- 1 2 Millington 2001a, p. 318.

- ↑ Newman 1976, II, pp. 473–76.

- ↑ Cited in Spencer 2000, p. 93

- ↑ Newman 1976, II, pp. 540–542.

- ↑ Newman 1976, II, pp. 559–567.

- ↑ Burk 1950, p. 405.

- ↑ Cited in Daverio 2008, p. 116. Letter from Richard Wagner to Mathilde Wesendonck, April 1859

- ↑ Deathridge 1984.

- ↑ Newman 1976, III, pp. 8–9.

- ↑ Gregor-Dellin 1983, pp. 315–320.

- ↑ Burk 1950, pp. 378–379.

- ↑ Gregor-Dellin 1983, pp. 293–303.

- ↑ Gutman 1990, pp. 215–216.

- ↑ Burk 1950, pp. 409–428.

- 1 2 3 Millington 2001a, p. 301.

- ↑ Wagner 1992, p. 667.

- ↑ Gregor-Dellin 1983, pp. 321–330.

- ↑ Newman 1976, III, pp. 147–148.

- ↑ Newman 1976, III, pp. 212–220.

- ↑ Cited in Gregor-Dellin 1983, pp. 337–338

- ↑ Gregor-Dellin 1983, pp. 336–338.

- ↑ Gutman 1990, pp. 231–232.

- ↑ Cited in Gregor-Dellin 1983, p. 338

- ↑ Gregor-Dellin 1983, p. 339.

- ↑ Gregor-Dellin 1983, p. 346.

- ↑ Wagner 1992, p. 741.

- ↑ Wagner 1992, p. 739.

- ↑ Gregor-Dellin 1983, p. 354.

- ↑ Newman 1976, III, p. 366.

- ↑ Millington 2001a, pp. 32–33.

- ↑ Newman 1976, III, p. 530.

- ↑ Newman 1976, III, p. 496.

- ↑ Newman 1976, III, pp. 499–501.

- ↑ Newman 1976, III, pp. 538–539.

- ↑ Newman 1976, III, pp. 518–519.

- ↑ Millington 2001a, pp. 287, 290.

- ↑ Wagner 1994c, 391 and n; Spotts 1994, pp. 37–40

- ↑ Gregor-Dellin 1983, p. 367.

- ↑ Gutman 1990, p. 262.

- ↑ Hilmes 2011, p. 118.

- ↑ Millington 2001a, p. 17.

- ↑ Millington 2001a, p. 311.

- ↑ Weiner 1997, p. 123.

- ↑ Gregor-Dellin 1983, p. 400.

- 1 2 Spotts 1994, p. 40.

- ↑ Newman 1976, IV, pp. 392–393.

- ↑ Gregor-Dellin 1983, pp. 409–418.

- ↑ Spotts 1994, pp. 45–46.

- ↑ Gregor-Dellin 1983, pp. 418–419.

- ↑ Körner (1984), 326.

- ↑ Marek 1981, p. 156.

- ↑ Gregor-Dellin 1983, p. 419.

- ↑ Cited in Spotts 1994, p. 54

- ↑ Spotts 1994, p. 11.

- ↑ Millington 2001a, p. 287.

- ↑ Spotts 1994, pp. 61–62.

- ↑ Spotts 1994, pp. 71–72.

- ↑ Newman 1976, IV, pp. 517–539.

- ↑ Spotts 1994, pp. 66–67.

- ↑ Cosima Wagner 1994, p. 270.

- ↑ Newman 1976, IV, p. 542 This was equivalent at the time to about $37,500.

- ↑ Gregor-Dellin 1983, p. 422.

- ↑ Newman 1976, IV, p. 475.

- ↑ Millington 2001a, p. 18.

- ↑ Newman 1976, IV, pp. 605–607.

- ↑ Newman 1976, IV, pp. 607–610.

- ↑ Millington 2001a, pp. 331–332, 409 The later essays and articles are reprinted in Wagner 1995e.

- ↑ Stanley 2008, pp. 154–156.

- ↑ Wagner 1995a, pp. 149–170.

- ↑ Millington 2001a, p. 19.

- ↑ Gutman 1990, pp. 414–417.

- ↑ Newman 1976, IV, p. 692.

- ↑ Newman 1976, IV, pp. 697, 711–712.

- ↑ Cormack 2005, pp. 21–25.

- ↑ Newman 1976, IV, pp. 714–716.

- ↑ The WWV is available online Archived 12 March 2007 at the Wayback Machine in German (accessed 30 October 2012)

- ↑ Coleman 2017, pp. 86–88.

- ↑ Millington 2001a, pp. 264–268.

- ↑ Millington 2001a, pp. 236–237.

- ↑ Wagner 1995b, pp. 299–304.

- ↑ Millington 2001a, pp. 234–235.

- ↑ See e.g. Dahlhaus 1995, pp. 129–136

- ↑ See also Millington 2001a, pp. 236, 271

- ↑ Millington 2001a, p. 274–276.

- ↑ Magee 1988, p. 26.

- ↑ Wagnerjahr 2013 Archived 7 February 2013 at the Wayback Machine website, accessed 14 November 2012

- ↑ e.g. in Spencer 2008, pp. 67–73 and Dahlhaus 1995, pp. 125–129

- ↑ Cosima Wagner 1978, II, p. 996.

- ↑ von Westernhagen 1980, pp. 106–107.

- ↑ Skelton 2002.

- ↑ Millington 2001a, pp. 276, 279, 282–283.

- ↑ See Millington 2001a, p. 286; Donington (1979) 128–130, 141, 210–212.

- ↑ Millington 2001a, pp. 239–240, 266–267.

- ↑ Millington 2008, p. 74.

- ↑ Grey 2008, p. 86.

- ↑ Millington 2002c.

- ↑ Millington 2001a, pp. 294, 300, 304.

- ↑ Dahlhaus 1979, p. 64.

- ↑ Deathridge 2008, p. 224.

- ↑ Rose 1981, p. 15.

- ↑ Millington 2001a, p. 298.

- ↑ McClatchie 2008, p. 134.

- ↑ Gutman 1990, pp. 282–283.

- ↑ Millington 2002a.

- ↑ See e.g. Weiner 1997, pp. 66–72

- ↑ Millington 2001a, pp. 294–295.

- ↑ Millington 2001a, p. 286.

- ↑ Puffett 1984, p. 43.

- ↑ Puffett 1984, pp. 48–49.

- ↑ Millington 2001a, p. 285.

- ↑ Millington 2001a, p. 308.

- ↑ Cosima Wagner 1978, II, p. 647. Entry of 28 March 1881..

- ↑ Stanley 2008, pp. 169–175.

- ↑ Newman 1976, IV, pp. 578. Letter from Wagner to the King of 19 September 1881..

- ↑ Kienzle 2005, p. 81.

- ↑ von Westernhagen 1980, p. 138.

- ↑ Millington 2001a, p. 311–312.

- ↑ Millington 2001a, p. 314.

- ↑ von Westernhagen 1980, p. 111.

- ↑ Deathridge 2008, pp. 189–205.

- ↑ Kennedy 1980, p. 701, Wedding March.

- ↑ Millington 2001a, p. 193.

- ↑ Millington 2001a, p. 194.

- ↑ Millington 2001a, pp. 194–195.

- ↑ Millington 2001a, pp. 185–186.

- ↑ Millington 2001a, p. 195.

- ↑ Wagner 1983.

- ↑ Treadwell 2008, p. 191.

- ↑ "Richard Wagner Schriften (RWS). Historisch-kritische Gesamtausgabe" [Richard Wagner Writings (RWS). Historical-Critical Complete Edition] (in German). University of Würzburg. Retrieved 5 February 2021.

- ↑ "Richard-Wagner-Briefausgabe" (in German). Universität Würzburg. Retrieved 5 February 2021.

- ↑ Deathridge 2008, p. 114.

- ↑ Magee 2000, pp. 208–209.

- ↑ See articles on these composers in The New Grove Dictionary of Music and Musicians; Grey 2008, pp. 222–229; Deathridge 2008, pp. 231–232

- ↑ de La Grange 1973, pp. 43–44.

- ↑ Millington 2001a, p. 371.

- ↑ Taruskin 2009, pp. 5–8.

- ↑ Magee 1988, p. 54.

- ↑ Grey 2008, pp. 228–229.

- ↑ Grey 2008, p. 226.

- ↑ Wagner 1995a, pp. 289–364.

- ↑ Westrup 1980, p. 645.

- ↑ Wagner 1995b, pp. 231–253.

- ↑ von Westernhagen 1980, p. 113.

- ↑ Reissman 2004.

- ↑ Sheffield, Rob (21 April 2021). "A Toast to Jim Steinman: The Songwriting Powder Keg Who Kept Giving Off Sparks". Rolling Stone. Retrieved 15 May 2022.

- ↑ Joe 2010, p. 23, n.45.

- ↑ "Volkswagner". Laibach. Retrieved 24 December 2012.

- ↑ Long 2008, p. 114.

- ↑ Millington 2001a, p. 396.

- 1 2 3 Magee 1988, p. 52.

- ↑ Penrose, James F. (September 2020). "The "old sorcerer"". The New Criterion. Vol. 39, no. 1. New York: Foundation for Cultural Review. p. 63. Retrieved 16 June 2023.

- ↑ Magee 1988, pp. 49–50.

- ↑ Grey 2008, pp. 372–387.

- ↑ Magee 1988, pp. 47–56.

- ↑ Cited in Magee 1988, p. 48

- ↑ Painter 1983, p. 163.

- ↑ Martin 1992, passim.

- ↑ Ross 2008, p. 136.

- ↑ Magee 1988, p. 47.

- ↑ Horton 1999.

- ↑ Magee 2000, p. 85.

- ↑ Picard 2010, p. 759.

- ↑ Adorno (2009), pp. 34–36.

- ↑ Zenk, Christina (2017). "Die "Walküren" und kein Ende: Eine Systematisierung von Referenztypen in Filmen". Archiv für Musikwissenschaft (in German). 74 (2): 78–102. ISSN 0003-9292. JSTOR 26332326. Retrieved 19 May 2023.

- ↑ Grant 1999.

- ↑ Giovetti, Olivia (10 December 2011). "Silver Screen Wagner Vies for Oscar Gold". WQXR-FM. Retrieved 15 April 2012.

- ↑ Sontag 1980; Kaes 1989, pp. 44, 63

- ↑ Millington 2001a, p. 26, 127.

- ↑ Sietz & Wiegandt 2001.

- ↑ François-Sappey 1991, p. 198. Letter from Alkan to Hiller 31 January 1860.

- ↑ Cited in Lockspeiser 1978, p. 179. Letter from Claude Debussy to Pierre Louÿs, 17 January 1896

- ↑ Ross 2008, p. 101.

- ↑ Cited in Michotte 1968, pp. 135–136; conversation between Rossini and Emile Naumann, recorded in Naumann 1876, IV, p. 5

- ↑ Deathridge 2008, p. 228.

- ↑ cf. Shaw 1898

- ↑ "Richard-Wagner-Verband-International". International Association of the Wagner Societies. Archived from the original on 5 June 2011. Retrieved 1 February 2013.

- ↑ Warshaw 2012, pp. 77–78.

- ↑ See entries for these films at the Internet Movie Database (IMDb).

- ↑ Faber Music News 2007, p. 2.

- ↑ Management record Archived 28 January 2013 at the Wayback Machine at Bayreuth Festival website, accessed 26 January 2013.

- ↑ Statutes of the Foundation (in German) Archived 17 October 2010 at the Wayback Machine at Bayreuth Festival website, accessed 26 January 2013.

- ↑ Magee 2000, pp. 11–14.

- ↑ Weiner 1997, p. 11; Katz 1986, p. 19; Conway 2012, pp. 258–264; Vaszonyi 2010, pp. 90–95

- ↑ Millington 2001a, p. 164.

- ↑ Conway 2012, p. 198.

- ↑ See Gutman 1990 and Adorno 2009, pp. 12–13

- ↑ Gutman 1990, p. 4.

- ↑ Conway 2002.

- ↑ Everett (2020).

- ↑ Gutman 1990, p. 418 ff.

- ↑ Beckett 1981.

- ↑ Gutman 1990, p. 406.

- ↑ Shaw 1898, Introduction.

- ↑ Millington 2008, p. 81.

- ↑ Lukacs, György (1937). "Richard Wagner as a "True Socialist"". Литературные теории XIX века и марксизм" (Nineteenth Century Literary Theories and Marxism). Translated by P., Anton. Moscow: State Publishing House of the USSR.

- ↑ Lunacharsky, Anatoly (1965) [1933]. "Richard Wagner (On the 50th Anniversary of His Death)". On Literature and Art. Translated by Pyman, Avril. Moscow: Progress Publishers.

- ↑ Donington 1979, pp. 31, 72–75.

- ↑ Nattiez 1993.

- ↑ Millington 2008, pp. 82–83.

- ↑ Cited in Spotts 1994, p. 141

- ↑ Spotts 1994, pp. 140, 198.

- ↑ See Karlsson 2012, pp. 35–52

- ↑ Carr 2007, pp. 108–109.

- ↑ Allen 2013, p. 80.

- ↑ Biddiss, Michael (n.d.) "Chamberlain, Houston Stewart" in Oxford Dictionary of National Biography

- ↑ Carr 2007, pp. 109–110. See also Field 1981.

- ↑ See Potter 2008, passim

- ↑ Calico 2002, pp. 200–2001; Grey 2002, pp. 93–94

- ↑ Carr 2007, p. 184.

- ↑ Chandler, Andrew; Stokłosa, Katarzyna; Vinzent, Jutta. Exile and Patronage: Cross-cultural Negotiations Beyond the Third Reich. Münster: LIT Verlag. p. 4.

- ↑ Fackler 2007. See also the Music and the Holocaust website.

- ↑ E.g. in Walsh 1992

- ↑ See Bruen 1993

Sources

Primary

- Wagner, Richard (1983). Borchmeyer, Dieter (ed.). Richard Wagner Dichtungen und Schriften [Richard Wagner Seals and Writings] (10 vols.). Berlin: Insel Verlag.

- Wagner, Richard (1987). Spencer, Stewart; Millington, Barry (eds.). Selected Letters of Richard Wagner. Translated by Spencer, Stewart; Millington, Barry. London: Dent. ISBN 978-0-393-02500-2.

- Wagner, Richard (1992). My Life. Translated by Gray, Andrew. New York: Da Capo Press. ISBN 978-0-306-80481-6.

- Wagner, Richard (1992). Collected Prose Works. Translated by Ellis, W. Ashton.

- Wagner, Richard (1994c). The Artwork of the Future and Other Works. Vol. 1. Lincoln (NE) and London: University of Nebraska Press. ISBN 978-0-8032-9752-4.

- Wagner, Richard (1995d). Opera and Drama. Vol. 2. Lincoln (NE) and London: University of Nebraska Press. ISBN 978-0-8032-9765-4.

- Wagner, Richard (1995c). Judaism in Music and Other Essays. Vol. 3. Lincoln (NE) and London: University of Nebraska Press. ISBN 978-0-8032-9766-1.

- Wagner, Richard (1995a). Art and Politics. Vol. 4. Lincoln (NE) and London: University of Nebraska Press. ISBN 978-0-8032-9774-6.

- Wagner, Richard (1995b). Actors and Singers. Vol. 5. Lincoln (NE) and London: University of Nebraska Press. ISBN 978-0-8032-9773-9.

- Wagner, Richard (1994a). Religion and Art. Vol. 6. Lincoln (NE) and London: University of Nebraska Press. ISBN 978-0-8032-9764-7.

- Wagner, Richard (1994b). Pilgrimage to Beethoven and Other Essays. Vol. 7. Lincoln (NE) and London: University of Nebraska Press. ISBN 978-0-8032-9763-0.

- Wagner, Richard (1995e). Jesus of Nazareth and Other Writings. Vol. 8. Lincoln (NE) and London: University of Nebraska Press. ISBN 978-0-8032-9780-7.

Secondary

Books and chapters

- Adorno, Theodor (2009). In Search of Wagner. Translated by Rodney Livingstone. London: Verso Books. ISBN 978-1-84467-344-5.

- Žižek, Slavoj. "Foreword: Why is Wagner Worth Saving". In Adorno (2009), pp. viii–xxvii.