The appearance and character of Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart are the subject of multiple investigations at present.[1] The fact that it has not been possible to exhume Mozart's remains – due to the exact location of the community grave in which he was buried being unknown – nor are masks or mortuary casts preserved,[note 1] lends a degree of uncertainty to the composer's physical appearance. Although an alleged skull of Mozart exists, its authenticity, more than questionable, has not been verified to date. This skull has been subjected to various DNA tests, comparing it with those of his alleged niece and maternal grandmother, but not only did they find that the former's DNA did not match those of his two relatives, but also that theirs did not match each other either.[2] Also, an alleged lock of his hair of dubious legitimacy has been preserved. However, there are reliable sources and references concerning both his appearance and clothing as well as his personality. This information is found in artworks, descriptions, and testimonies of the time, which allow us to get a more or less accurate idea of what Mozart was like physically and psychologically.

Regarding his clothing and personal effects, recent studies based on documents such as the Order of Suspension[note 2] drawn up after his death or the record of receipts for the purchase of costumes, have done much to shed light on Mozart's tastes in clothing.

As for his personality, knowledge of it is mainly due to the descriptions of his contemporaries that have been preserved, as well as to the analysis of the composer's extensive personal correspondence.[3]

Physical appearance

As Franz Xaver Niemetschek, one of his early biographers, wrote, "there was nothing special in [his] physique. [...] He was small and his countenance, except for his large, intense eyes, showed no sign of his genius."

Mozart was described by tenor Michael Kelly,[note 3] actor and Irish singer of the Vienna Opera, in his work Reminiscences. This provides one of the most valuable and complete descriptions of Mozart's figure:[5][6]

He entertained visitors by playing fantasias and capriccios on the piano. His sensitivity, his feeling, the speed of his fingers and, above all, the agility and power of his left hand, left me absorbed. After the splendid performance, we would sit at the dinner table, and I had the honor of sitting between him and his wife. After dinner, if the occasion was propitious and there were more guests, they would all march to the ball, and Mozart would join them with great enthusiasm. Physically, he was a man of small build, very thin and of pale complexion, with abundant hair, though somewhat thin and fair, of which he was, by the way, very proud. I remember that once he invited me to his house and I stayed there for a long time, where I was always received with hospitality and esteem; on that occasion I could see his great fondness for punch, which he mixed with other drinks and ingested, in truth with little moderation. He was very fond of billiards, and we played many games together, although he always beat me. He was a kind-hearted man, and his spirit was constantly ready to please others. He was only somewhat different when he played his music: he was capable of interrupting his performance if he heard the slightest noise. He gave concerts every Sunday, which I do not remember missing on any occasion.

From direct accounts of the composer's physique, various specialists on Mozart's life conclude that he was a man of small stature (approximately 150 centimeters/5 feet)[7] and was very thin and pale.[8] His short height is attested by the diary of Count Ludwig von Bentheim-Steinfurt, Mozart's contemporary aristocrat who attended one of his concerts, held on 15 October at the Vienna Municipal Theater, at which Mozart performed several pieces.[9] In the entry for October 15, the count states that "Herr Mozart is a small man, of pleasing figure."[6][10] His pallor, short stature and thinness are also attested to by some comments written in 1792 by Maria Anna Mozart, Wolfgang's sister, for the future biography of Friedrich Schlichtegroll:[11][12]

Mozart's parents were the best-looking couple in Salzburg of their time, and in their younger years the daughter passed for possessing remarkable beauty. But the son, Wolfgang, was small, thin, of pale complexion and without any extraordinary appearance in his outward appearance and figure.

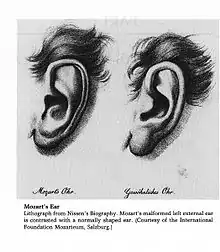

He had an ordinary face, which was marked by the scars of the smallpox he suffered in his childhood, and in which a large nose stood out. His eyes were large and clear (apparently a deep blue color) and he sported a thick headful of hair, with fine, wheat-colored strands pulled back in a ponytail.[note 4] His hands were medium-sized, with long, slender fingers, and his mouth was small. Mozart's left ear was missing the usual circumvolution or concha (this rare congenital malformation is now known in medical literature under the name "Mozart's ear").[note 5][13][14]

He was rather clumsy in manipulating objects, all the more so the smaller they were, and he could not stop fiddling or drumming his hands when talking to someone or when eating: his body was always in motion.[15]

For her part, Constanze later wrote that "he was a tenor, rather soft in oratory and delicate in singing, but when something excited him, or it was necessary to exert himself, he was as powerful as he was energetic."[16][17]

Illnesses

Given his thin and weak build, Mozart was from the age of six a person who suffered from numerous illnesses throughout his life, which gradually deteriorated his health until leading to his death[18] at age thirty-five.[19] Thus, he contracted a streptococcal infection in the upper airways in 1762, later suffering from erythema nodosum, which Dr. Peter J. Davies of St. Vincent's Hospital in Melbourne (Australia) considers to be of probable streptococcal origin. In the same year, he contracted a new streptococcal infection and suffered a mild attack of rheumatic fever. In 1764, he suffered from tonsillitis, and in 1765 he contracted it again, in this case complicated with sinusitis. At the end of that year, he suffered a endemic typhoid fever that led to a coma, the following year he suffered a new attack of rheumatic fever. In 1767, he contracted smallpox, three years later he would suffer frostbite during his travels in Italy, and in 1771 he suffered from tracheobronchitis with jaundice. Three years later, he suffered an acute tooth abscess, and four years after that, he suffered from bronchitis.[20][21]

At the age of twenty-five, in 1781, he contracted a viral infection, but it was in 1784 when he suffered a serious illness in Vienna, whose symptoms are terrible colics ending in violent vomiting, and inflammatory rheumatic fever, which could have originated a chronic kidney disease. This infection is considered to be the origin of his death seven years later. In 1787, Mozart "again contracted a streptococcal infection which gave rise to a second occurrence of Henoch–Schönlein purpura; in addition, his kidneys, already in poor condition, were further damaged."[20][22]

Portraits and paintings of the composer

Currently, there are more than sixty[23][24] Mozart portraits and pictorial representations of all kinds, despite the fact that much of them show little fidelity to the model.

Arthur Hutchings expressed his point of view about the contradiction offered by the opposition between the enormous amount of artworks that represent the genius and the scarce iconographic value of them with the sentence: "Too many images".[25] For his part, Alfred Einstein, also a Mozart specialist, expressed his opinion about these portraits in the following statement:[24][26]

We have nothing to give us an idea of Mozart's physical appearance, except for a few mediocre canvases that do not even resemble each other.

With the exception of French artist Jean-Baptiste Greuze, no other major painter undertook the task of faithfully reproducing Mozart's physique. On the other hand, one of the characteristics of the 18th century as far as painting is concerned was precisely, although only in some schools, the lack of fidelity to the features of the reproduced model.[24]

All this led the musicologist Arthur Schuring to state in 1923 the following:[24][27]

Mozart has been the famous composer of whom most fictitious portraits have been made, pictorial material that has contributed, not a little, to confuse later generations about his appearance.

These statements led the musicologists and art historians to undertake a rigorous analysis of all existing paintings, sketches, drawings, cameos and engravings of the composer. The conclusion of this was that only eight works of art,[24] all of them of unequal interest, were produced by authors who knew Mozart directly, or by sketches taken from drawings made from life. From this selection, Mozart's "biographical paintings" have been published with more care, generally following the criteria that emerged from this analysis.[24]

Thus, it seems appropriate to point out a list of authors, contemporaries of the composer, who signed loose portraits of Mozart:[33][34] Pompeo Girolamo Battoni, François Joseph Bosio, Breitkopf, Joseph Duplessis, Nicolò Grassi, Jean-Baptiste Greuze, Klass, Langernhöffel, Rigaud, Saint-Aubin, Van Smissen, Thelott, Tischbein, and Johann Zoffany. Nevertheless, the study of these portraits can be interesting since, although they are not faithful to the physical features of the composer, they provide important iconographic data, either on musical instruments, or on other personalities that appear in them.[24]

To all the above list of authors, including some great names in painting, we should add all the artists of the 19th century who represented Mozart, such as Hermann von Kaulbach (whose portrait of the composer is reproduced in the left margin) or Shields, who offer a purely romantic and not very rigorous vision of the physical appearance of the genius of Salzburg. From this statement we should exclude the portrait painted by Barbara Krafft in 1819 since, despite having been painted almost thirty years after the composer's death, it is considered one of his most faithful representations. This is because Krafft relied on portraits made during Mozart's lifetime and considered by the composer's sister to bear a strong resemblance to the genius. Thus, Krafft took as models the family portrait by Della Croce (1780–1781) and the unfinished oil painting by Joseph Lange (1789–1790, reproduced in the right margin), which were provided to her by Mozart's own sister, in Salzburg.[32]

Apart from any iconographic study, the current knowledge about the similarity of the portraits with respect to the figure of Mozart is rather based on opinions that are a reliable source, such as, for example, the testimony and descriptions of some of his friends, his wife or his eldest son, Karl Thomas Mozart.[34]

Finally, it is worth mentioning that the portrait of Mozart by his brother-in-law, Joseph Lange (c. 1789, depicted in the right margin) is now considered to be the most accurate representation of the composer. Lange was the husband of Constanze's older sister, Aloysia Weber, and worked as an actor at the Burgtheater in Vienna. Despite being only an amateur painter, his work was considered by Constanze to be the best of all portraits of her husband,[28][31] stating:[29][30]

Undoubtedly, the one painted by Madame Lange's husband, which, although it is an unfinished work, bears an admirable resemblance.

Maria Anna Mozart, sister of the composer, also admitted that the portrait's resemblance to the model was uncanny.[35]

Clothing

Mozart, like Constanze, was fond of elegant clothes, and always wore the latest fashions and expensive dresses, regardless of his financial situation. This was partly because he was a man who attached great importance to outward appearance.[36]

Mozart was intensely socially active, including such duties as appearing at court functions,[note 6] visiting the elegant halls of the likes of Johann Tost and the chancellor of the Greiner court, and frequenting Prague court circles and receptions in his capacity as Hofcompositeur.[note 7] His wife attended many of these events; this meant that the Mozarts had to be well dressed, and Mozart's hair required constant attention. On the latter point, the direct testimony of his hairdresser, herr Haderlein, has been preserved:[37][38]

While I was doing Mozart's hair one morning, just as I was finishing his ponytail, Mozart suddenly jumped up and, although I was still holding his ponytail in my hands, he went into the next room, dragging me behind him, and began to play the piano. Admiring his playing and the beautiful tonality of the instrument – it was the first time I had ever heard a piano like that – I let go of his ponytail and did not finish combing his hair until he got up. One day, as I was turning the corner from Kärtnerstrasse into Himmelpfortgasse to go to Mozart's service, he rode up, stopped, and, as he walked a few steps forward, took a small tablet [out of his pocket] and began to write music. I spoke to him again, asking if he could receive me, and he said yes.

Musicologist Bernhard Paumgartner (1991) believes that Mozart not only attached importance to his appearance for social reasons, but also because he suffered from a lack of physical qualities.[39][40] The actor Backhaus is said to have taken him for a tailor's officer,[39] and to the poet Johann Ludwig Tieck, who saw him in Berlin in May 1789, hovering restlessly around the music stands of an empty, dark hall where The Abduction from the Seraglio (KV 384) was to be performed, he seemed a man of trivial figure.[41] Sociologist Norbert Elias (2002) also emphasizes the insignificance of his appearance, although he points out that his countenance is friendly and humanly pleasing.[42][43]

There is no information on how Constanze Mozart dressed, but we do know what her husband's clothing was like in 1791, thanks to the Order of Suspension[note 8] drawn up in December of the same year, after the genius' death. This document has an inventory of his clothing and personal effects:[36]

- 1 white cloth coat.

- 1 blue ditto.

- 1 red ditto.

- 1 ditto in nanquin color.[note 9]

- 1 ditto in brown satin [braun = marine brune?] with breeches, embroidered in silk.[note 10]

- 1 full suit of black cloth.

- 1 brown greatcoat.

- 1 ditto of lighter cloth.

- 1 blue cloth jacket with fur.

- 1 ditto Kiria with fur trim.

- 4 assorted vests, 9 assorted breeches, two ordinary hats, 3 pairs of boots, 3 pairs of shoes.

- 9 pairs of silk stockings.

- 9 shirts.

- 4 white handkerchiefs, 1 night cap, 18 pocket handkerchiefs.

- 8 underpants, 2 nightshirts, 5 pairs of socks.

Such a wardrobe was what a well-to-do merchant might have: these were expensive and luxurious clothes. Kelly recalled it in an essay as follows:

He was on stage with his crimson pince-nez and his bicorne with gold lace, giving the tempo of the music to the orchestra.

Mozart's wardrobe appears to have been purchased according to the latest fashion; according to H. C. Robbins Landon, musicologist and specialist in Mozart's life and works, he probably had to acquire elegant clothes for the coronation festivities in Frankfurt,[44][note 11] for attendance at public concerts and private receptions.[37] The following excerpt from a contemporary newspaper gives an idea of the fashion of the time:[44]

Shorts have been worn for a long time... in worsted (for everyday wear) and in summer in straw color; also in ash gray and the couleur sur couleur striped nanquin (the latest fashion); also in off-white, greenish or sulfur-colored fabric... Another very used garment is the vest... Now they are beginning to wear plain, striped or checked Manchester [cotton].... Boots are also beginning to be worn... if shoes are worn it is with... pearl gray silk stockings. [The Coat] reaches almost to the shoes and is worn in all colors.

An illustration of "an elegant German dressed in the latest fashion" is included and his costume is described:

The elegant gentleman is a combination of English and French: 1) the hairstyle en Grecque carré à dos d'âne;[note 12] 2) an English handkerchief of black muslin; 3) an Anglo-French coat; 4) a vest en fond filoche;[note 13] 5) tight breeches en bleu mignon or strong blue worsted; 6) two large watch chains; 7) blue and white checked silk stockings; 8) black shoes are still worn; 9) in the hand a hat à l'Andromane, with rose-colored lining, because the hat is more for the hand than for the head.[45]

After the composer's death, his estate was valued at 595 guilders and 9 kreutzer, of which 55 guilders were for costumes and undergarments. Among the outstanding debts (totaling 918 guilders and 16 kreutzer) were three considerable bills including that of a tailor, to whom he owed 282 guilders and 7 kreutzer.[46]

Personality and beliefs

As numerous testimonies of the time claim, the most characteristic trait of Mozart's personality was his optimism. When the English musician and publisher couple Vincent and Mary Novello interviewed Constanze in 1829 and asked her about her husband's character, she replied without hesitation: "He was always cheerful."[30][47]

Most researchers point to Mozart's childish and even somewhat irresponsible character, which led him, at times, to make impulsive decisions.[48] This idea is supported in a text written in 1792 by Maria Anna Mozart, Wolfgang's sister, for the future biography of Friedrich Schlichtegroll:[11][12]

Except for his music he remained a child, and this is the main characteristic of the dark side of his personality: he always needed a father, a mother or someone to look after him; he was incapable of managing money; he married, against his father's will, a young woman who was not at all suitable for him, and hence the great disorder in his home during and after his death.

Mozart was also described by his contemporaries as a hospitable man,[34] generous,[49] jealous of his own genius[50] and a workaholic.[51] On the other hand, he had great self-esteem and could, at times, come across as somewhat proud. Although he was not endowed with great psychological strength, he reached his last days with surprising fortitude in every respect.[47] He was outgoing,[50] sociable[50] and nonconformist, since he refused to accept the "status" of servants that musicians had at the time, which caused him no small amount of trouble in the course of his existence.[52]

On this social nonconformism that Mozart displayed throughout his life, it is worth mentioning the parting of ways with who had been his patron and protector since childhood, Hieronymus von Colloredo, Prince-Archbishop of Salzburg, who had an excellent relationship with the composer's father.[note 14] Mozart never officially ceased to be a musician at the archiepiscopal court of Salzburg. Because of his cheerful and cosmopolitan spirit, the composer gradually distanced himself from the archbishop, who considered him "an insolent young man."[53] Colloredo summoned him to Vienna in 1781 to deliver an ultimatum for his irresponsible attitude; Mozart arrived in the city to meet him on 16 March. At this meeting, a harsh confrontation took place between the two, which led to the presentation of a letter of resignation by Mozart, and concluded with the famous "farewell kick" that Count Arco, a member of the archbishop's court, gave Mozart in the backside. The archbishop, aware of Mozart's worth as a composer, refused to sign the letter of resignation that Mozart had presented to him, making Mozart for the rest of his days a runaway vassal, a dangerous condition in 18th century Europe.[54]

In correspondence with his father, Mozart recounts how the meeting with Count Arco unfolded:[53]

What a way to soften people up! He did not dare, out of cowardice, to say anything to the Archbishop and kept me in suspense for a month before finally kicking me in the ass. That's a hell of a thing to do!

Leopold was deeply troubled by the fear of losing his salary, as Wolfgang wrote to him in anger, listing the numerous reprisals he planned to carry out against the count.

... I shall write very soon to that ill-fated man to tell him what I think of him, and as soon as he stands before my eyes I shall give him a kick that he will remember in his flesh forever... Although I am not a count, I have more gallantry and honor in my heart than many of those who enjoy such a title. Whoever insults me, be he a lackey or a count, will deserve my contempt.

In reality, Leopold's fears were unfounded, for Mozart was a man of peaceful, quiet and gentle character;[53] he was not much given to violence, and only in his writings do traces of physical vengeance surface.[53]

Mozart generally worked long and energetically, completing compositions at a great pace due to tight deadlines. He often made sketches and outlines although, unlike Ludwig van Beethoven, these have not been preserved, as Constanze destroyed them after his death.[55] With regard to his own compositions, Mozart was wont to judge them impartially, and often with a severity and rigor that he would not easily have endured from another person.[56]

When it came to money management, Mozart was rather carefree, but not as carefree as popular belief claims.[57] However, this attitude led him to spend it sometimes excessively,[49] and to depend for several years on loans made to him by some friends, especially Johann Michael Puchberg.[58][note 15] On the other hand, and since settling in Vienna, Mozart lived long periods of time during which he did not possess a fixed salary.[59] Once, on a trip the composer took to Berlin, King Frederick William II of Prussia offered him three thousand escudos in fees if he wished to take up residence at his court and take over the direction of his orchestra. Mozart refused the proposal, replying, "I like living in Vienna; the emperor loves me, and money matters little to me."[59][60] Music publishers and theater impresarios abused Mozart's well-known disinterest in money to such an extent that most of his piano compositions yielded him nothing.[61] Also, performances of Mozart's operas in Germany brought him fame, but no money, due to the non-existence of "performance rights"; and German publishers could reprint Mozart's music at will without consulting him, since there was no copyright law either.[62]

He was brought up according to Catholic morals, but without coercion or spiritual fetters that might divert the free initiative of genius.[63] He was a loyal member of the Catholic Church at all stages of his life,[64][65] despite belonging to Freemasonry for the last seven years of his life.[66] This was possible because in Mozart's time, Freemasonry was considered an enlightened extension of Christian beliefs, so that being Catholic and Mason was not mutually exclusive, but perfectly compatible.[67][68]

Training and intellectual qualities

Mozart was a cultured and enlightened person, fluent in four languages (German, Italian, French and English, and had advanced knowledge of Latin),[63] he experienced a deep interest in reading,[69] especially for the literature of William Shakespeare, and was drawn to the Fine Arts.[30][63] Leopold Mozart himself was very proud of the education he had provided for his son, boasting that Wolfgang had received a more solid culture than the boys who attended the celebrated Imperial School in Vienna, where the Haydn brothers and Schubert were trained, a school whose training included painstaking instruction in Latin and music, both instrumental and vocal.[63] Arthur Hutchings, musicologist and specialist in the life and work of Mozart, states that the genius received a fairly complete education, being suitable at least in the musical field: little Mozart found enjoyment in music.[63]

He possessed great skill in languages and in mathematics (especially algebra), his favorite childhood subject.[63][70] Moreover, he had absolute pitch, an innate quality invaluable in music, as well as a prodigious photographic and auditory memory, which enabled him to retain ideas in his head for years.[70] To these two qualities testifies the famous anecdote of the Miserere by Gregorio Allegri: this musicalization of the fiftieth psalm, one of the finest examples of Italian Renaissance polyphonic style, was performed twice every Holy Week, once on Holy Wednesday and once on Good Friday, in the Sistine Chapel. Considered patrimony of the Vatican, the execution of the work outside the Chapel was strictly forbidden, under penalty of excommunication for whoever copied it. However, on his trip to Italy in Holy Week of 1770, Mozart attended with his father the performance of the Wednesday Miserere in the Sistine Chapel, and made a point of retaining it by heart. Thus, when he returned that evening to the inn where he was staying, he put it in writing. Two days later, on Friday, he returned to witness the performance of that day and, hiding the manuscript in his hat, he was able to make some corrections. When the feat reached the ears of Pope Clement XIV, he not only did not excommunicate Mozart, then fourteen years old, but decided to award him a knighthood in the Order of the Golden Spur in the first degree.[71][72]

Environment

Mozart lived in the center of the Viennese musical world and knew a great number and variety of people: fellow musicians; theatrical performers; friends who, like him, had moved from Salzburg; and many aristocrats, including an acquaintance of the emperor Joseph II of Austria. He had numerous friends among the intellectuals, and he regularly attended the soirées held in the salons of prominent families where artists and thinkers met. However, his presence at such gatherings became increasingly sporadic as his ties with Freemasonry became tight.[63]

Maynard Solomon considers that the three closest friends of the composer may have been Gottfried Janequin, Count August Hatzfeld, and Sigmund Barisani. Many others included among his friendships his longtime colleague Joseph Haydn, the singers Franz Xaver Gerl and Benedikt Schack, and the horn Joseph Leutgeb. Leutgeb and Mozart maintained a curious kind of friendly banter, often with Leutgeb being the butt of Mozart's practical jokes.[73]

Hobbies

He enjoyed playing billiards, possibly because it was a form of exercise.[74][75] He also loved dancing, especially masquerades, which he always attended dressed as a harlequin.[76] He had several pets: a canary, a starling, a dog, and also a horse for playful riding.[77][78][79] There is not the slightest indication that Mozart engaged in gambling (except billiards or home card games, with small stakes), and he certainly did not go to the famous Viennese gambling dens, since, among other things, his purchasing power did not allow it.[80] He was fond of drinking coffee in a cup, as well as smoking a pipe, but in moderation.[81]

Especially in his youth, Mozart had a special predilection for scatological humor, not so unusual in his time, which is apparent in many of his surviving letters, especially those written to his cousin Maria Anna Thekla Mozart (around 1777 and 1778), but also in correspondence with his sister Nannerl and his parents.[82] Mozart even wrote scatological music, such as the canon Leck mich im Arsch KV 231 (literally "Lick my ass", sometimes idiomatically translated as "Kiss my ass.")[83]

Daily routine

As can be seen from a text written by Mozart himself, his daily program in 1782[note 16] was as follows:[77][84]

At six o'clock, I am always combed. At seven o'clock, fully dressed. Then I write until nine o'clock. From nine o'clock until one o'clock, I teach. Then I eat, when I am not invited, and in that case lunch is at two or three o'clock. I can't work before five or six o'clock, and often an academy prevents me from doing so;[note 17] otherwise, I write until nine o'clock at night [...]. Because of the academies and the eventuality of being asked here or there, I am never sure of being able to compose in the afternoon, so I have got into the habit (especially when I get back early) of writing something before I go to bed. I often do so until one o'clock, only to get up again at six o'clock.

Months after this writing, Mozart married Constanze Weber; therefore, his routine underwent certain modifications from that moment on.[78] Nevertheless, and as various entries in his diary after the marriage show, Mozart's daily life as a married man presented a rather similar organization, including some new activities, such as horseback riding in the early morning,[77][78][79] and billiard games with his wife in the afternoon.[74][75][85]

Compositional method

In general, Mozart worked energetically, finishing compositions at a great pace due to tight deadlines and the accumulation of commissions. He spent between five and seven hours a day composing, depending on whether he had a concert or not, which was usually divided between the early afternoon and the evening.[76][84]

At the present time, the speed with which Mozart composed is well known.[86] In a letter to his mother, the composer's sister, Nannerl Mozart, jokes that her brother is writing a sonata while he is mentally composing another one.[86]

Thus it took Mozart a month to write the Piano Concerto No. 21, eighty-three pages long – many composers would have taken a month just to copy a concerto of such dimensions.[86]

Mozart was able to write his Symphony "Linz", KV 425, in only five days, during his vacation period in the aforementioned city.[87] This fact is reflected in Wolfgang's correspondence with his father:[88][89]

On Tuesday, November 4, I will give an academy at the theater here, and as I do not have a single symphony at hand here, I am writing a new one on the spur of the moment, which must be finished by then...

— Letter from Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart to his father, dated Linz October 31, 1783.

Another example of his compositional speed is found in the overture of the opera Don Giovanni, on which Mozart worked only on the evening preceding the first performance and when the dress rehearsal had already taken place.[90]

Mozart was not in the habit of making copies of his compositions, so he wrote them directly in the final version, without resorting to a prior draft.[86][note 18] However, his autograph scores show surprisingly few corrections and revisions, since Mozart would put a work to paper only when it had already been completed in his mind.[86]

Mozart used to follow a very peculiar compositional process, which was characterized by the fact that he did not finish a work completely, but left blank spaces in the sheet music that he was sure he would be able to remember after a while, and when the date of delivery or premiere of the work approached, he would fill in the empty spaces. In this way, he was able to optimize the time spent working on the various compositions, giving preference to those whose delivery or premiere dates were closest.[91]

Thus, Mozart's usual method of working was to complete the first violins part, the second violins if necessary, and the bass and remaining parts, usually of a solo nature, if he deemed it necessary to aid his memory.[91]

In the case of a large vocal work, such as the Great Mass (KV 427) or the Requiem (KV 626), Mozart notated the choir, the basso continuo and the ritornello sections of the orchestral and also usually the first violins and the complicated polyphonic or canonic entries of the strings or the solo sections of the woodwind instruments.[91]

With such a particella, Mozart could have kept even a work of importance for up to three years, as he did with the Piano Concerto No. 27 (KV 595), then dust it off and "refill" it in due course.[91]

See also

Notes

- ↑ The count Joseph Deym von Strižtež alias Müller, made two death masks of Mozart on the same night of his death, from which he made a wax statue that he exhibited, together with one of the masks, in the art gallery he ran (Kunstkabinett Müller). He gave the other mask to Constanze, who, after a few years, broke it "unintentionally" (she always said that the accident had been fortuitous, but there is enough data to affirm that its destruction was intentional). As for the mask and the wax statue that Müller kept, their traces were lost upon the collector's death in 1804 Landon (2005, p. 247 n. 25).

- ↑ In German Sperrs-Relation, list of belongings carried out after the death of a person. See Deutsch (1961, p. 495), and Landon (2005, p. 36).

- ↑ Because of his friendship with Mozart, Kelly was the first performer of the roles of Don Curzio and Don Basilio in the opera The Marriage of Figaro. See Andrés, p. 51.

- ↑ In his life's later years, he did not wear wig, but sported his own hair. See Landon (2005, p. 36).

- ↑ See margin image.

- ↑ He had to conduct the orchestra at the numerous court balls at which his compositions were performed. See Landon (2005, p. 36)

- ↑ Id est, "Court Composer."

- ↑ In German Sperrs-Relation, an account of belongings of a person carried out after their death. See Deutsch (1961, p. 495), and Landon (2005, p. 36).

- ↑ Id est', yellow or suede color.

- ↑ Mozart wore it at the concert given in Frankfurt on 15 October 1790. See Deutsch (1961, Dokumente, p. 329) ("wearing a luxuriously embroidered navy blue satin suit").

- ↑ Reference is made to the coronation of Emperor Leopold II of Austria as king of Bohemia, in the year 1791. For the celebrations of that event, Mozart composed his penultimate opera, La clemenza di Tito, which was premiered at the National Theater in Prague on September 6, conducted by the composer himself. See Landon (2005, ch. IX: "Coronation Diary")

- ↑ In English it would translate as hairstyle en Grecque carré à dos d'âne, id est hair curled and thrown back in many tiny curls, topped in a ponytail; Mozart's hairstyle shown in Lange's unfinished portrait of 1789–1790 (reproduced in the right margin).

- ↑ Id est', with silk fabric base.

- ↑ Leopold Mozart held the position of concertmaster in the archiepiscopal orchestra, and composed numerous works for the archbishop. Although he criticized him harshly in correspondence with Wolfgang, he always showed submission and respect for Colloredo. See Deutsch (1961, p. 31).

- ↑ Johann Michael Puchberg (1741–1822) was an Austrian merchant, friend and brother Mason of Mozart and, at the time, treasurer of the lodge Zur wahren Eintracht. See Landon (2005, p. 23).

- ↑ This text was written by Mozart himself, and reflects his daily routine at the age of twenty-six, a year after he had taken up residence in Vienna, and a few months before he married Constanze Weber at St. Stephen's Cathedral, Vienna. See Sollers.

- ↑ Id est, a concert.

- ↑ Probably, the reason Mozart avoided making drafts of his compositions was the time savings involved. See Grout, Burkholder & Palisca (2008, p. 629, footnote to illustration 22.3)

References

- ↑ Einstein 1953, Foreword.

- ↑ For more information about this alleged skull of Mozart, see the article Death of Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart.

- ↑ For Mozart's correspondence, see Mozart

- ↑ Nissen, Georg Nikolaus von (1972). Biographie W. A. Mozarts nach Originalbriefen. Photographic reprint of the original edition. Hildesheim.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ↑ Hutchings, pp. 15–16.

- 1 2 Andrés, p. 51.

- ↑ Hutchings, ch. 1.

- ↑ Stendhal, p. 58.

- ↑ Landon 2005, p. 20.

- ↑ Landon 2005, p. 21.

- 1 2 Landon (2005, p. 218)

- 1 2 Deutsch (1961, Briefe, IV, pp. 199 f.)

- ↑ Davies, pp. 437–442, 560 ff.

- ↑ See Nissen.

- ↑ Stendhal, p. 59.

- ↑ Solomon, p. 308.

- ↑ Hutchings, p. 21.

- ↑ Landon 2005, p. 203.

- ↑ For more information about the causes of Mozart's death, see the article Death of Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart.

- 1 2 Davies, pp. 437–442

- ↑ Landon 2005, p. 204.

- ↑ Landon 2005, p. 205.

- ↑ Sixty-two to be precise, according to Bory (1948)

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 Hutchings, p. 14.

- ↑ Hutchings, ch. I: "He was always cheerful".

- ↑ Einstein 1953, p. .

- ↑ Schuring (1923)

- 1 2 Andrés, p. 56)

- 1 2 Hutchings, p. 16)

- 1 2 3 4 See Novello.

- 1 2 Landon (2005, p. 72)

- 1 2 Andrés, pp. 60–61)

- ↑ Zenger (1941–1942)

- 1 2 3 Hutchings, p. 15

- ↑ Andrés, p. 57.

- 1 2 Landon (2005, p. 37)

- 1 2 Landon (2005, p. 36)

- ↑ See Pfannhausser.

- 1 2 Andrés, p. 52.

- ↑ See Paumgartner (1991)

- ↑ Andrés, pp. 52–53.

- ↑ Andrés, p. 53.

- ↑ Elias 2002.

- 1 2 Landon (2005, pp. 235–236)

- ↑ Landon 2005, p. 261 n. 3.

- ↑ Landon 2005, pp. 38–39.

- 1 2 Hutchings, p. 11.

- ↑ Stendhal, pp. 59–60.

- 1 2 Stendhal, p. 74.

- 1 2 3 Hutchings, p. 13.

- ↑ Stendhal, ch. VI.

- ↑ Hutchings, ch. 5.

- 1 2 3 4 Hutchings, p. 117.

- ↑ Hutchings, ch. 5: "From Servitude to Freedom."

- ↑ Solomon, p. 310.

- ↑ Stendhal, p. 73.

- ↑ For more on Mozart's finances, salary, and debts, see Landon (2005, pp. 22ff, 38ff, 56ff, 83ff, 172, 246 n. 12, 251 n. 5).

- ↑ Landon 2005, pp. 23, 42, 47 et seq, 58, 73f, 83, 243 n. 12..

- 1 2 Stendhal, p. 75.

- ↑ Landon 2005, p. 244 n. 15.

- ↑ Stendhal, p. 76.

- ↑ Landon 2005, p. 23.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 Hutchings, p. 12.

- ↑ Einstein 1945, p. 77.

- ↑ For more information about the relationship between Mozart and the Catholic Church, see the article Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart and the Catholic Church.

- ↑ For more information about the relationship between Mozart and Freemasonry, see the article Mozart and Freemasonry.

- ↑ Landon 2005, ch. VI: "Midnight for the Masons".

- ↑ Landon 1982.

- ↑ Hutchings, pp. 11–12.

- 1 2 Stendhal, chap. I: "Of his childhood."

- ↑ Hutchings, pp. 66–73.

- ↑ Stendhal, pp. 43–48.

- ↑ Solomon, sec. 20.

- 1 2 Niemetschek, p. 72.

- 1 2 Landon (2005, p. 217)

- 1 2 Sollers, p. 216

- 1 2 3 Lorenz.

- 1 2 3 Sollers, ch. II.

- 1 2 Solomon, p. 319.

- ↑ Landon 2005, p. 39.

- ↑ See Sollers.

- ↑ Solomon, p. 169.

- ↑ According to its idiomatic English translation from Schemann (1997).

- 1 2 Stendhal, p. 68.

- ↑ Landon 2005, p. 38.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Grout, Burkholder & Palisca (2008, p. 629, footnote to illustration 22.3.)

- ↑ Landon 2005, p. 173.

- ↑ Landon 2005, p. 257 n. 2..

- ↑ Mozart, Briefe, III, p. 291.

- ↑ Stendhal, pp. 69–70.

- 1 2 3 4 Landon (2005, p. 246 n. 7)

Sources

- Andrés, Ramón (2006). Mozart: su vida y su obra (in Spanish). Barcelona: Ma Non Troppo (Ediciones Robinbook). p. 233. ISBN 84-95601-50-8.

- Bory, Robert (1948). La vie de W. A. Mozart par l'image (in French).

- Davies, Peter J. (1984). "Mozart's Illnesses and Death". Journal of the Royal Society of Medicine. Musical Times. 215 (1): 85. PMC 1439543. PMID 20894511.

- Deutsch, Otto Erich (1961). Mozart: die Dokumente seines Lebens (in German). Vol. II. Edition by the author. Kassel.

- Einstein, Alfred (1945). Mozart, His Character, His Work. Oxford University Press.

- Einstein, Alfred (1953). Mozart: Sein Charakter, sein Werk (in German). Stuttgart.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - Elias, Norbert (2002). Mozart. Sociología de un genio (in Spanish). Edition by Michael Schröter, translation by Marta Fernández-Villanueva and Oliver Strunk. Barcelona: Ediciones Península. ISBN 84-297-3341-8.

- Grout, Donald J.; Burkholder, J. Peter; Palisca, Claude V. (2008). Historia de la música occidental (in Spanish). Translation by Gabriel Menéndez Torrellas (7th ed.). Madrid: Alianza Editorial. ISBN 978-84-206-9145-9.

- Hutchings, Arthur (1986). Mozart (in Spanish). Translation by Ramón Andrés. Barcelona: Salvat. p. 192. ISBN 84-345-8145-0.

- Lorenz, Michael. "Mozart's Apartment on the Alsergrund".

- Mozart, Wolfgang Amadeus (1997). Cartas (in Spanish). Translation by Miguel Sáenz. Barcelona: El Aleph. p. 296. ISBN 84-7669-297-8.

- Niemetschek, Franz Xaver (1956). Life of Mozart... Translation by Helen Mautner with an introduction by A. Hyatt King. London.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - Nissen, Georg Nikolaus von (1972). Biographie W. A. Mozarts nach Originalbriefen (in German). Hildesheim.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - Novello, Vincent; Novello, Mary. Hughes, Rosemary (ed.). A Mozart Pilgrimage, Being the Travel Diaries of Vincent and Mary Novello in the year 1829. Transcribed and compiled by Nerina Medici di Marignano. London.

- Paumgartner, Bernhard (1991). Mozart (in Spanish). Madrid: Alianza Editorial.

- Pfannhausser, Karl (1971). Epilogomena Mozartiana (in Spanish). Mozart-Jahrbuch.

- Landon, H. C. Robbins (1982). Mozart and the Masons. New Light on the Lodge "Crowned Hope". London and New York. ISBN 9780500550144.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - Landon, H. C. Robbins (2005). 1791: El último año de Mozart (in Spanish). Translation by Gabriela Bustelo and Beatriz del Castillo. Madrid: Siruela. p. 288. ISBN 84-7844-908-6.

- Schemann, Hans (1997). English-German Dictionary of Idioms. New York: Routledge. ISBN 0-415-17254-3.

- Schuring, Arthur (1923). Wolfgang Amadé Mozart. Vol. 2. Leipzig.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - Sollers, Philippe (2003). Misterioso Mozart (in Spanish). Translation by Anne-Hélène Suárez. Barcelona: Alba editorial. p. 216. ISBN 84-8428-186-8.

- Solomon, Maynard (1995). Mozart: A Life. New York: Harper Perennial. ISBN 0-06-092692-9.

- Stendhal (2000). Vida de Mozart (in Spanish). Translation by Consuelo Berges. Barcelona: Alba Editorial S. L. p. 136. ISBN 84-8428-041-1.

- Zenger, Max (1941). Falsche Mozartbilonisse (in German). Munich: Mozart-Jahrbuch.

Further reading

- Bär, Carl (1972). Mozart:Krankheit-Tod-Bregräbnis (in German). Salzburg.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - Dalchow, Johannes; Duda, Gunther; Kerner, Dieter (1971). Mozarta Tod 1791-1971. Pähl.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - Dibelius, Ulrich (1971). Mozart-Aspekte (in German). Munich.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - Deutsch, Otto Erich (1962). Mozart: Briefe und Aufzeichnungen (in German). The work consists of seven volumes: letters (four volumes, authors' edition), 1962-1963; commentary (two volumes, Joseph Heinz Eibl edition), 1971; indexes (one volume, Joseph Heinz Eibl edition), 1975. Kassel.

- Fariña Pérez, Luis Ángel (2014). Patobiografía de Mozart (PDF) (in Spanish). Madrid: YOU&US.

- López Calo, José; Torres, J.; Téllez, José Luis; Dini, J.; Reverter, Arturo (1981). Los Grandes Compositores: "Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart" (in Spanish). Pamplona: Salvat.

- Massin, Jean; Massin, Briggite (1987). Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart (in Spanish). Translation by Isabel de Asumendi. Madrid: Turner. p. 1538. ISBN 84-7506-596-1.

- Rochlitz, Friedrich. Verbürgte Anekdoten aus Wolfgang Gottlieb Moarts Leben: ein Beytrag zur richtigeren Kenntnis dieses Mannes, als Mensch und Künstler (in German). Serialized from issue 2 (October 10, 1798) to December 1798. Allgemeine musikalische Zeitung.

- Schenk, Erich (1960). Mozart: Sein Leben, seine Welt. Munich: 1975.