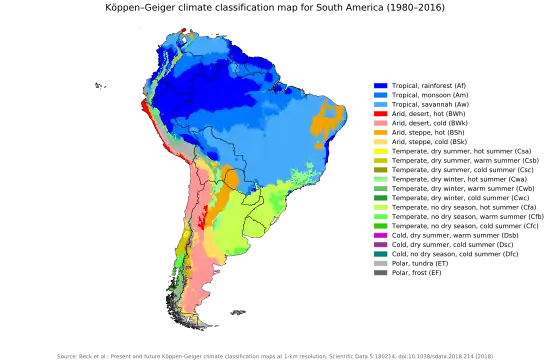

The Arid Diagonal (Spanish: diagonal árida/arreica) is a contiguous zone of arid and semi-arid climate that traverses South America from coastal Peru in the Northwest to Argentine Patagonia in Southeast including large swathes of Bolivia and Chile.[1] The Arid Diagonal encompasses a number of deserts, for example: Sechura, Atacama, Monte and the Patagonian Desert.

The Arid Diagonal acts to isolate the temperate and subtropical forests of Chile and southern Argentina from other forests of South America.[2] Together with the Quaternary glaciations in the Southern Andes, the diagonal has controlled the distribution of vegetation throughout Chile and Argentina.[3]

The concept of a South American Arid Diagonal was first coined by French geographer Emmanuel de Martonne in his 1935 work Problème des régions arides Sud-Américaines.[4] However, few works dealing with the Arid Diagonal mention this foundational text.[4] The original Arid Diagonal of de Martonne went from Antofagasta in northern Chile to the northern coast of Argentine Patagonia.[4] however, other authors like Margarita González Loyarte (1995) later extended it to the coast of northern Peru.[4]

Cause and origin

The northern portion of the Arid Diagonal is a result of the blocking of the trade winds by the barrier formed by the Central Andes and the South Pacific High.[5] To the south in the westerlies, the rain shadow that the Southern Andes casts over eastern Patagonia similarly blocks moisture.[1] South of Mendoza (32°53' S), the driest parts of the diagonal move away from the Andes as the mountains lose height, causing some humidity to penetrate; thus, at more southern latitudes the driest parts of the diagonal lie on the Atlantic coast of Patagonia.[1]

The Arid Diagonal has existed since the Neogene.[3] The origin of the aridity of northern part of the diagonal is linked to two geologic events: a) the rise of the Andes — an event that led to the permanent block of both the westward flow of moisture along the tropics, and the eastward flow of moisture in Patagonia[6] and b) the permanent intrusion of cold Antarctic waters (the Humboldt Current) along South America's west coast.[5] Together with the Quaternary glaciations in the Southern Andes, the diagonal controls the distribution of the vegetation types over Chile and Argentina.[3]

References

- 1 2 3 Bruniard, Enrique D. (1982). "La diagonal árida Argentina: un límite climático real". Revista Geográfica (in Spanish): 5–20.

- ↑ Villagrán, Carolina; Hinojosa, Luis Felipe (1997). "Historia de los bosques del sur de Sudamérica, II: Análisis fitogeográfico". Revista Chilena de Historia Natural (in Spanish). 70: 241–267.

- 1 2 3 Villagrán, Carolina; Hinojosa, Luis Felipe (2005). "Esquema biogeográfico de Chile". In Llorente Bousquests, Jorge; Morrone, Juan J. (eds.). Regionalización Biogeográfica en Iberoámeríca y tópicos afines (in Spanish). Mexico: Ediciones de la Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México, Jiménez Editores.

- 1 2 3 4 Abraham, Elena María; Rodríguez, María Daniela; Rubio, María Clara; Guida-Johnson, Bárbara; Gomez, Laura; Rubio, Cecilia (2020-01-08). "Disentangling the concept of "South American Arid Diagonal"". Journal of Arid Environments. 175: 104089. Bibcode:2020JArEn.175j4089A. doi:10.1016/j.jaridenv.2019.104089. S2CID 213655544.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: date and year (link) - 1 2 Armesto, Juan J.; Arrollo, Mary T.K.; Hinojosa, Luis F. (2007). "The Mediterranean Environment of Central Chile". In Veblen, Thomas T.; Young, Kenneth R.; Orme, Anthony R. (eds.). Physical Geography of South America. Oxford University Press. pp. 184–199.

- ↑ Folguera, Andrés; Encinas, Alfonso; Echaurren, Andrés; Gianni, Guido; Orts, Darío; Valencia, Víctor; Carrasco, Gabriel (2018). "Constraints on the Neogene growth of the central Patagonian Andes at the latitude of the Chile triple junction (45–47°S) using U/Pb geochronology insynorogenic strata". Tectonophysics. 744: 134–154. Bibcode:2018Tectp.744..134F. doi:10.1016/j.tecto.2018.06.011. hdl:11336/88399. S2CID 135214581.