.jpg.webp)

The Armenian National Constitution (Armenian: Հայ ազգային սահմանադրութիւն Hay azkayin sahmanatroutioun; French: Constitution nationale arménienne) or Regulation of the Armenian Nation (Ottoman Turkish: Nizâmnâme-i Millet-i Ermeniyân, نظامنامهٔ ملّت ارمنیان) was the 1863 Ottoman Empire-approved form of the "Code of Regulations" composed of 150 articles which define the powers of Patriarch (position in Ottoman Millet) and newly formed "Armenian National Assembly".[1] This code is still active among Armenian Church in diaspora.[1] The Ottoman Turkish version was published in the Düstur.[2]

The document itself was called a "constitution" in Armenian, while the Ottoman Turkish version was instead called a "regulation" on the millet.[2]

History

Hatt-ı Hümayun's (1856) organisation to bring equality among millets also brought the discontent of the Armenian Patriarchate.[3] Before the Hatt-ı Hümayun, the Armenian Patriarch was not only the spiritual leader of the community, but its secular leader (of all Armenians - the Armenian nation) as well. The Patriarch could at will dismiss the Bishops and his jurisdiction extended to 50 areas. The revolutionary Armenians wanted to abolish what they saw as oppression by the nobility, drawing up a new `National Regulation'.[3] The "Code of Regulations" (1860) was drafted by members of the Armenian intelligentsia (Dr. Nahabet Rusinian, Dr. Servichen, Nigoghos Balian, Krikor Odian and Krikor Margosian). They primarily sought to define the powers of Patriarch.

Finally the Council accepted the draft regulation on May 24, 1860, and presented it to the Sublime Porte (Bâb-ı Âli). The government of Sultan Abdülaziz ratified it (with some minor changes) by a firman on March 17, 1863, and made it effective. The Armenian National Constitution (Ottoman Turkish:"Nizâmnâme-i Millet-i Ermeniyân") was Ottoman Empire approved form of the "Code of Regulations" composed of 150 articles which defined the powers of Patriarch (his position in Ottoman Millet) and newly formed "Armenian National Assembly".[1]

The Armenian Patriarch began to share his powers with the Armenian National Assembly and limited by the Armenian National Constitution. He perceived the changes as erosion of his community.[3]

It defined the condition of Armenians within the state, but also it had regulations defining the authority of the Patriarch. The constitution of Armenian National Assembly seen as a milestone by progressive Armenians. It attempted to define Armenia as a modern nation. The reforms which resulted in the Armenian National Assembly came about as individual Armenians and pressure group complained frequently for assistance against injustices perpetuated by the Kurds (seen as feudal) and corrupt officialdom. At the beginning the relations were positive but in the 1860s, the Ottomans, having crushed Kurdish resistance, no longer needed Armenian support, and the Empire became less responsive to Armenian claims.[4]

Henry Finnis Blosse Lynch, author of Armenia, Travels and Studies, wrote in the second volume, published in 1901, that the Armenian National Constitution was "practically in abeyance owing to the strained relations at present existing between the Palace and the Armenians."[5]

References

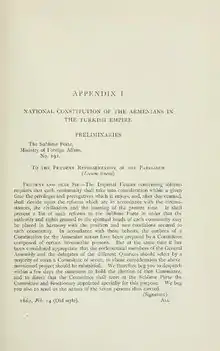

- Lynch, Harry Finnis Blosse (1901). "Appendix I: National Constitution of the Armenians in the Turkish Empire". Armenia, Travels and Studies. Vol. 2. Longmans, Green and Co. p. 445-467. (PDF p. 573-595/644)

Notes

- 1 2 3 Richard G. Hovannisian "The Armenian People from Ancient to Modern Times", page 198

- 1 2 Strauss, Johann (2010). "A Constitution for a Multilingual Empire: Translations of the Kanun-ı Esasi and Other Official Texts into Minority Languages". In Herzog, Christoph; Malek Sharif (eds.). The First Ottoman Experiment in Democracy. Wurzburg. p. 21-51.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) (info page on book at Martin Luther University) - Cited: p. 37 (PDF p. 39) - 1 2 3 Mekerditch-B. Dadian, "La société arménienne contemporaine", Revue des deux Mondes, June 1867, pp. 903-928, read online

- ↑ Edmund Herzig "Armenians Past And Present In The Making Of National Identity A Handbook" page.75

- ↑ H. F. B. Lynch, Vol. II, p. 467.

Further reading

Copies of the Armenian constitution:

- "Armenian National Constitution" (in Armenian). Endangered Archives Programme.

- Dustur, Constantinople (Istanbul), 1289, II, pp. 938-961. - Ottoman Turkish version

- Artinian, Vartan (2004). Osmanlı Devleti'nde Ermeni Anayasası'nın Doğuşu 1839-1863. Translated by Zülal Kılıç. Istanbul: Aras Yayıncılık. - Copies of the Ottoman constitution in Armenian and Armeno-Turkish are in the appendix

- Lynch, Harry Finnis Blosse (1901). "Appendix I: National Constitution of the Armenians in the Turkish Empire". Armenia, Travels and Studies. Vol. 2. Longmans, Green and Co. p. 445-467. (PDF p. 573-595/644) - English translation of the Armenian constitution

- Young, George (1905). "Réglement de la Communauté Arménienne Grégorienne 14 mai 1860". Corps de droit ottoman (in French). Vol. 2. pp. 79-92. - French translation

- "Constitution nationale des arméniens / traduite de l'arménien sur le document original, par M. E. Prud'homme" (in French). Paris: B. Duprat. 1862 – via National Library of France.

External links

- "Ազգային սահմանադրութիւնը". digilib.aua.am. American University of Armenia.