| Part of a series on the |

| Indo-Greek Kingdom |

|---|

|

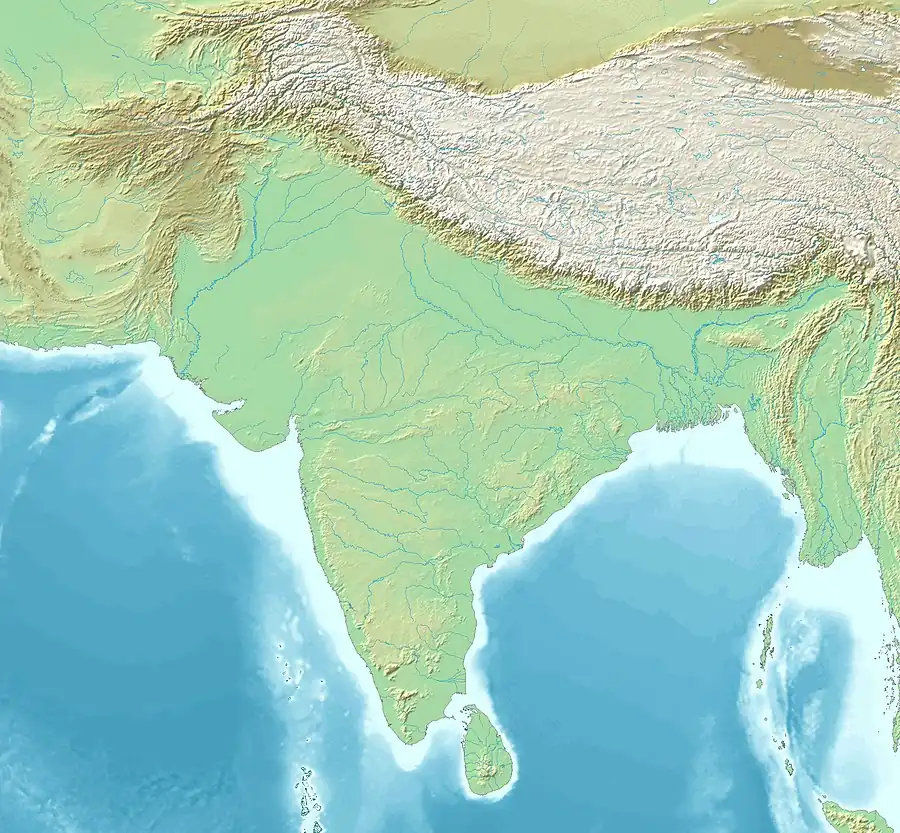

Indo-Greek art is the art of the Indo-Greeks, who reigned from circa 200 BCE in areas of Bactria and the Indian subcontinent. Initially, between 200 and 145 BCE, they remained in control of Bactria while occupying areas of Indian subcontinent, until Bactria was lost to invading nomads. After 145 BCE, Indo-Greek kings ruled exclusively in parts of ancient India, especially in Gandhara, in what is now present-day the northwestern Pakistan. The Indo-Greeks had a rich Hellenistic heritage and artistic proficiency as seen with the remains of the city of Ai-Khanoum, which was founded as a Greco-Bactrian city.[2] In modern-day Pakistan, several Indo-Greeks cities are known such as Sirkap near Taxila, Barikot, and Sagala where some Indo-Greek artistic remains have been found, such as stone palettes. Some Buddhist cultural objects related to the Indo-Greeks are known, such as the Shinkot casket. By far the most important Indo-Greek remains found are numerous coins of the Indo-Greek kings, considered as some of the most artistically brilliant of Antiquity.[3] Most of the works of art of the Greco-Buddhist art of Gandhara are usually attributed to the direct successors of the Indo-Greeks in Ancient India in the 1st century CE, such as the nomadic Indo-Scythians, the Indo-Parthians and, in an already decadent state, the Kushans.[4] Many Gandharan works of art cannot be dated exactly, leaving the exact chronology open to interpretation. With the realization that the Indo-Greeks ruled in India until at least 10-20 CE with the reign of Strato II in the Punjab, the possibility of a direct connection between the Indo-Greeks and Greco-Buddhist art has been reaffirmed recently.[5][6][7]

Early Indo-Bactrian period (200-145 BCE)

The first Indo-Greek kings, also sometimes called "Indo-Bactrian", from Demetrius I (200–190 BCE) to Eucratides (170–145 BCE) ruled simultaneously,the areas of Bactria and northwestern India, until they were completely expelled from Bactria and the eastern Bactrian capital city of Ai-Khanoum by invading nomads, probably the Yuezhi, or possibly the Sakas, circa 145 BCE.[8][9][10] While Demetrius, the first Indo-Greek king, was extending his territory into India, still held Ai-Khanoum as one of his strongholds and continued to mint some of his coinage in the city.[11] The last Greek coinage in Ai-Khanoum was by Eucratides.[12] Because of their dual territorial possessions in Bactria and India, these kings, starting with Demetrius I, are variously described as Indo-Greek,[13] Indo-Bactrian,[14] or Greco-Bactrian.[15] After losing Bactria around circa 145 BCE during the rule of Eucratides and Menander I, the Greeks were generally called as "Indo-Greeks" only.

The main known remains from this period are the ruins and artifacts of their city of Ai-Khanoum, a Greco-Bactrian city founded circa 280 BCE which continued to flourish during the first 55 years of the Indo-Greek period until its destruction by nomadic invaders in 145 BCE, and their coinage, which is often bilingual, combining Greek with the Indian Brahmi script or Kharoshthi.[16] Apart from Ai-Khanoum, Indo-Greek ruins have been positively identified in few cities such as Barikot or Taxila, with generally much fewer known artistic remains.[9][17]

Architecture in Bactria

Numerous artefacts and structures were found, particularly in Ai-Khanoum, pointing to a high Hellenistic culture, combined with Eastern influences, starting from the 280-250 BCE period.[18][19][20] Overall, Aï-Khanoum was an extremely important Greek city (1.5 sq kilometer), characteristic of the Seleucid Empire and then the Greco-Bactrian Kingdom, remaining one of the major cities at the time when the Greek kings started to occupy parts of India, from 200 to 145 BCE. It seems the city was destroyed, never to be rebuilt, about the time of the death of king Eucratides around 145 BC.[20]

Archaeological missions unearthed various structures, some of them perfectly Hellenistic, some other integrating elements of Persian architecture, including a citadel, a Classical theater, a huge palace in Greco-Bactrian architecture, somehow reminiscent of formal Persian palatial architecture, a gymnasium (100 × 100m), one of the largest of Antiquity, various temples, a mosaic representing the Macedonian sun, acanthus leaves and various animals (crabs, dolphins etc...), numerous remains of Classical Corinthian columns.[20] Many artifacts are dated to the 2nd century BCE, which corresponds to the early Indo-Greek period.

Ai- Khanoum mosaic (central detail in color).

Ai- Khanoum mosaic (central detail in color). Architectural antefixae with Hellenistic "Flame palmette" design, Ai-Khanoum.

Architectural antefixae with Hellenistic "Flame palmette" design, Ai-Khanoum. Sun dial within two sculpted lion feet.

Sun dial within two sculpted lion feet. Winged antefix, a type only known from Ai-Khanoum.

Winged antefix, a type only known from Ai-Khanoum.

Sculpture

Various sculptural fragments were also found at Ai-Khanoum, in a rather conventional, classical style, rather impervious to the Hellenizing innovations occurring at the same time in the Mediterranean world. Of special notice, a huge foot fragment in excellent Hellenistic style was recovered, which is estimated to have belonged to a 5-6 meter tall statue (which had to be seated to fit within the height of the columns supporting the Temple). Since the sandal of the foot fragment bears the symbolic depiction of Zeus' thunderbolt, the statue is thought to have been a smaller version of the Statue of Zeus at Olympia.[2][21]

Due to the lack of proper stones for sculptural work in the area of Ai-Khanoum, unbaked clay and stucco modeled on a wooden frame were often used, a technique which would become widespread in Central Asia and the East, especially in Buddhist art. In some cases, only the hands and feet would be made in marble.

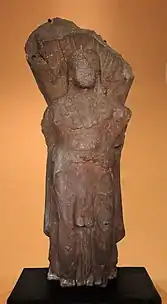

In India, only a few Hellenistic sculptural remains have been found, mainly small items in the excavations of Sirkap.

Sculpture of an old man. Ai-Khanoum, 2nd century BC.

Sculpture of an old man. Ai-Khanoum, 2nd century BC. Close-up of the same statue.

Close-up of the same statue. Frieze of a naked man wearing a chlamys. Ai-Khanoum, 2nd century BC.

Frieze of a naked man wearing a chlamys. Ai-Khanoum, 2nd century BC. Hellenistic gargoyle. Ai-Khanoum, 2nd century BC.

Hellenistic gargoyle. Ai-Khanoum, 2nd century BC.

Artefacts

A variety of artefacts of Hellenistic style, often with Persian influence, were also excavated at Ai-Khanoum, such as a round medallion plate describing the goddess Cybele on a chariot, in front of a fire altar, and under a depiction of Helios, a fully preserved bronze statue of Herakles, various golden serpentine arm jewellery and earrings, a toilet tray representing a seated Aphrodite, a mold representing a bearded and diademed middle-aged man. Various artefacts of daily life are also clearly Hellenistic: sundials, ink wells, tableware. An almost life-sized dark green glass phallus with a small owl on the back side and other treasures are said to have been discovered at Ai-Khanoum, possibly along with a stone with an inscription, which was not recovered. The artefacts have now been returned to the Kabul Museum after several years in Switzerland by Paul Bucherer-Dietschi, Director of the Swiss Afghanistan Institute.[22]

Bronze Herakles statuette. Ai-Khanoum. 2nd century BC.

Bronze Herakles statuette. Ai-Khanoum. 2nd century BC. Bracelet with horned female busts. Ai-Khanoum, 2nd century BC.

Bracelet with horned female busts. Ai-Khanoum, 2nd century BC. Stone recipients from Ai-Khanoum. 3rd-2nd century BC.

Stone recipients from Ai-Khanoum. 3rd-2nd century BC. Imprint from a mold found in Ai-Khanoum. 3rd-2nd century BC.

Imprint from a mold found in Ai-Khanoum. 3rd-2nd century BC.

First Indo-Greek coinage

Demetrius I, the son of Euthydemus is generally considered as the Greco-Bactrian king who first launched the Greek expansion into Ancient India circa 190-180 BCE, and is therefore the founder of the Indo-Greek realm and the first recognized Indo-Greek king.[24][19] The first Indo-Greek kings, having dominions in Bactria as well as India, continued to strike coins in standard Greco-Bactrian style, but conjointly started to strike coins on the Indian standard having bilingual Indian-Greek legends.[16][2]

After the death of Demetrius, the Bactrian kings Pantaleon and Agathocles struck the first bilingual coins with Indian inscriptions found as far east as Taxila,[25] so in their time (c. 185–170 BC) the Bactrian kingdom seems to have included Gandhara.[26] These first bilingual coins used the Brahmi script, whereas later kings would generally use Kharoshthi. They also went as far as incorporating Indian deities, variously interpreted as Hindu deities or the Buddha.[1][16] They also included various Indian devices (lion, elephant, zebu bull) and symbols, some of them Buddhist such as the tree-in-railing.[27] These symbols can also be seen in the Post-Mauryan coinage of Gandhara.

The Hinduist coinage of Agathocles is few but spectacular. Six Indian-standard silver drachmas were discovered at Ai-Khanoum in 1970, which depict Hindu deities.[16][28] These are early Avatars of Vishnu: Balarama-Sankarshana with attributes consisting of the Gada mace and the plow, and Vasudeva-Krishna with the Vishnu attributes of the Shankha (a pear-shaped case or conch) and the Sudarshana Chakra wheel.[28] These first attempts at incorporating Indian culture were only partly preserved by later kings: they all continued to struck bilingual coins, sometimes in addition to Attic coinage, but Greek deities remained prevalent. Indian animals however, such as the elephant, the bull or the lion, possibly with religious overtones, were used extensively in their Indian-standard square coinage. Buddhist wheels (Dharmachakras) still appear in the coinage of Menander I and Menander II.[29][30]

In Ai-Khanoum, numerous coins were found, down to Eucratides, but none of them later. Ai-Khanoum also yielded unique coins of Agathocles, consisting of six Indian-standard silver drachms depicting Hindu deities. These are the first known representations of Vedic deities on coins, and they display early Avatars of Vishnu: Balarama-Samkarshana and Vasudeva-Krishna, and are thought to correspond to the first attempts at creating an Indian-standard coinage as they invaded northern India.[16]

| Territory/Ruler | Agathocles (190-180 BCE) | Pantaleon (190-180 BCE) | Apollodotus I (circa 180 BCE) | Eucratides (171-145 BCE) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Bactria |

|

|

|

|

|

India |

|

|

|

|

artefacts in Bactria

Ancient Indian artefacts were also found in the treasure room of the city, probably brought back by Eucratides from his Indian campaigns, which show a level of artistic interaction between Indian and the Greeks at that time. A narrative plate made of shell inlaid with various materials and colors, thought to represent the Indian myth of Shakuntala was recovered.[31] Also, numerous Indian punch-marked coins were found, about 677 of them in the Palace area of Ai-Khanoum alone, suggesting intense exchanges between Bactria and India.[16][32]

Greek cities in the subcontinent

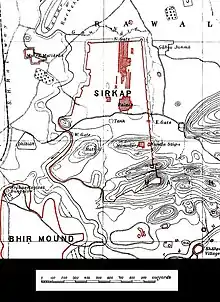

The first Indo-Greek ruler Demetrius I is said to have built the city of Sirkap, in modern-day Pakistan.[33] The site of Sirkap was built according to a "Hippodamian" grid-plan characteristic of Greek cities.[34] It is organized around one main avenue and fifteen perpendicular streets, covering a surface of around 1,200 by 400 meters (3,900 ft × 1,300 ft), with a surrounding wall 5–7 meters (16–23 ft) wide and 4.8 kilometers (3.0 mi) long. The ruins are Greek in character, similar to those of Olynthus in Macedonia. Numerous Hellenistic artifacts have been found, in particular coins of Greco-Bactrian kings and stone palettes representing Greek mythological scenes. Some of them are purely Hellenistic, others indicate an evolution of the Greco-Bactrian styles found at Ai-Khanoum towards more indianized styles. For example, accessories such as Indian ankle bracelets can be found on some representations of Greek mythological figures such as Artemis.

_03.jpg.webp) Some remains at Sirkap.

Some remains at Sirkap. Map of Sirkap excavations.

Map of Sirkap excavations. Sirkap at time of excavations.

Sirkap at time of excavations. Excavations at Sirkap.

Excavations at Sirkap.

Main Indian period (145 BCE-20 CE)

The main Indian period of the Indo-Greeks starts with the reign of Menander (from c. 165/155 BC) who has been described as the greatest of the Indo-Greek Kings.[35]

The remains of the Greeks in South Asia essentially revolve around city ruins, stone palettes, a few Buddhist artefacts, and their abundant coinage.

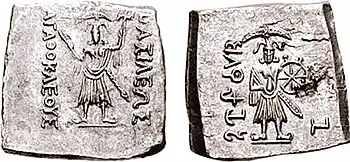

Coinage

The Indo-Greek kings continued the tradition of minting bilingual coinage in India. Paradoxically, they were not as bold as earlier kings such as Agathocles or Pantaleon is showing Indian divinities. They all continued to struck bilingual coins, sometimes in addition to Attic coinage, but Greek deities remained prevalent. Indian animals however, such as the elephant, the bull or the lion, possibly with religious overtones, were used extensively in their Indian-standard square coinage. Buddhist wheels (Dharmachakras) appear in the coinage of Menander I and Menander II.[29][30]

Famous Indian-standard coinage of Menander I with wheel design.

Famous Indian-standard coinage of Menander I with wheel design. Coin of Antialcidas (105–95 BC), with elephant accompanying Zeus

Coin of Antialcidas (105–95 BC), with elephant accompanying Zeus Coin of Menander II (90–85 BCE), with seated Zeus and Nike on his arm, extending a victory wreath over a wheel symbol

Coin of Menander II (90–85 BCE), with seated Zeus and Nike on his arm, extending a victory wreath over a wheel symbol Coin of Strato II (25 BCE-10 CE), one of the last Indo-Greek kings.

Coin of Strato II (25 BCE-10 CE), one of the last Indo-Greek kings.

Architecture

Besides the amin city of Sirkap, founded by Demetrius I, an expeditions in the 1980s and 90s discovered an Indo-Greek town in Barikot from around the time of King Menander I in the 2nd century BCE. The 2nd century BCE town covered, at its peak, an area of about 10 ha (25 acres) including the acropolis, or about 7 ha (17 acres) without. It was surrounded by a defensive wall about 2.7 meters thick with massive rectangular bastions and a moat, and was structurally similar to other Hellenistic fortified cities such as Ai-Khanoum or Sirkap.[38][39] Indo-Greek coins were found, especially in the layers associated with the wall's construction, as well as potsherds with Greek letters.[38]

The Indo-Greeks are also known for their involvement in the construction of a few architectural elements. In 115 BC, that the embassy of Heliodorus, from king Antialkidas to the court of the Sungas king Bhagabhadra in Vidisha, is recorded. In the Sunga capital, Heliodorus established the Heliodorus pillar in a dedication to Vāsudeva. This would indicate that relations between the Indo-Greeks and the Sungas had improved by that time, that people traveled between the two realms, and also that the Indo-Greeks readily followed Indian religions.[40]

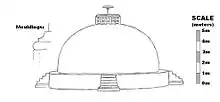

A coin of Menander I was found in the second oldest stratum (GSt 2) of the Butkara stupa suggesting a period of additional constructions during the reign of Menander.[41] It is thought that Menander was the builder of the second oldest layer of the Butkara stupa, following its initial construction during the Maurya empire.[42] These elements tend to indicate the importance of Buddhism within Greek communities in northwestern India, and the prominent role Greek Buddhist monks played in them, probably under the sponsorship of Menander.

Ruins of the city of Barikot

Ruins of the city of Barikot Ruins of the Indo-Greek city of Barikot

Ruins of the Indo-Greek city of Barikot_03.jpg.webp)

The Butkara stupa as expanded during the reign of Menander I.

The Butkara stupa as expanded during the reign of Menander I.

Indo-Greek artefacts in India

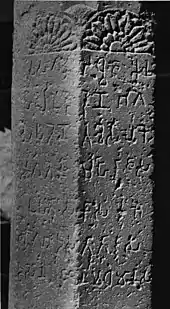

Few artefacts are known with certainty to belong to the Indo-Greeks. The Shinkot casket, a Buddhist relic casket was dedicated during the reign of Menander I, bearing his name in an inscription.[44]

Stone palettes (circa 100 BCE)

Stone palette, also called "toilet tray" or "cosmetic trays") is a round tray commonly found in the areas of Bactria and Gandhara, and which usually represent Greek mythological scenes. Some of them are attributed to the Indo-Greek period in the 2nd and 1st century BCE. A few were retrieved from the Indo-Greek stratum No.5 at Sirkap. Some stone palettes with some very pure Hellenistic designs are thought to date to circa 100 BCE, and to have come from Taxila.[46] Other have mythological themes, such as the Rape of Europa, which "could have only been made by a Greek patron during the Indo-Greek period".[47]

Intaglio gems

Intaglio gems from northwest India, showing an evolution from Greek workmanship to more degraded forms, range from circa 2nd century BCE to 2nd century CE.[48]

Inscriptions and sculptures

Some inscriptions remain mentioning Indo-Greek rule, such as the Yavanarajya inscription, mentioned the rule of the Indo-Greeks in Mathura from the reign of Menander I to the period circa 50 BCE.[49] Stone art and architecture began being produced at Mathura at the time of Indo-Greek hegemony over the region.[50] Some authors consider that Indo-Greek cultural elements are not particularly visible in the art of Mathura, and Hellenistic influence is not more important than in other parts of India.[51] Others consider that Hellenistic influence appears in the liveliness and the realistic details of the figures (an evolution compared to the stiffness of Mauryan art), the use of perspective from 150 BCE, iconographical details such as the knot and the club of Heracles, the wavy folds of the dresses, or the depiction of bacchanalian scenes.[50][52] The art of Mathura became extremely influential over the rest of India, and was "the most prominent artistic production center from the second century BCE".[50]

Excavation at Semthan in southern Kashmir have revealed a Greek settlement.[53] Many figurines in the Hellenistic style were found during the excavations.[54] The female figurines are fully dressed, with the left leg slightly bent, and wear the Greek chiton and himation, and the Hellenistic styles of Bactria are probably the ultimate source of these designs.[54][55] It is thought that the Indo-Greeks introduced their artistic styles into the area as they moved eastward from the area of Gandhara into South Kashmir.[56]

Such Hellenistic draped figurines have not been found at Taxila or Charsadda, although they are known to have been Greek cities, but probably this is mainly because excavations to Greek levels have been very limited: in Sirkap, only one eight of the excavations were made down to the Indo-Greek and early Saka levels, and only in an area far removed from the center of the ancient city, where few finds could be expected.[57]

Terracotta statuette in Chiton and Himation, Semthan, Southern Kashmir

Terracotta statuette in Chiton and Himation, Semthan, Southern Kashmir Male Hellenistic dress, Semthan

Male Hellenistic dress, Semthan Semthan, female Hellenistic dresses

Semthan, female Hellenistic dresses

Buddhist reliquaries

According to Harry Falk Buddhist stone reliquaries, which were generally place insided stupas with precious relics of the Buddha or other saints, are directly derived from the stone pyxis which have been excavated at Ai-Khanoum and originated in the west.[58] The Ai-Khanoum stone containers are thought to have played a religious role, and were apparently used to burn incense.[58] The shapes, material, and decoration are very similar to the later Buddhist containers, down to the compartmentalization inside the containers themselves.[58] One such containers the Shinkot casket, is a Buddhist relics container which was engraved with the name of the Indo-Greek king Menander I.[44][60]

The Bimaran reliquary, with one of the earliest known images of the Buddha, is generally dated to a period corresponding the end of Indo-Greek rule circa 1-15 CE, but was actually deposited by one of the Indo-Scythian successors of the Indo-Greeks, names Kharahostes.[61] The Bimaran casket already displays a combination of Hellenistic design elements with Indian ones, such as the arches and the lotus design.[62]

The Shinkot casket, a Buddhist relics container in the name of Menander I

The Shinkot casket, a Buddhist relics container in the name of Menander I

The Bimaran reliquary is often dated to circa 1-15 CE, at the time of the last Indo-Greek kings.

The Bimaran reliquary is often dated to circa 1-15 CE, at the time of the last Indo-Greek kings.

Architecture and statuary under the Indo-Greeks in Mathura (180-70 BCE)

Architecture

From time of the Mauryan Empire, India was able to use as an example the architectural work of the Greco-Bactrians and the Indo-Greeks from the 3rd to the 1st centuries BCE, with influences which are clearly visible in the Hellenistic designs, such as flame palmettes, beads and reels used and adapted from that time in Indian art.[64]

Stone statuary

150-100 BCE

Following the demise of the Mauryan Empire and its replacement by the Sunga Empire in eastern India, numismatic, literary and epigraphic evidence suggest that the Indo-Greeks, when they invaded India, occupied the area of Mathura for close to a century from circa 180 BCE and the time of Menander I until approximately 70 BCE, with the Sungas remaining eastward of Mathura.[72][50] An inscription in Mathura discovered in 1988,[73][74] the "Yavanarajya inscription", mentions "The last day of year 116 of Yavana hegemony (Yavanarajya)", suggesting the presence of the Indo-Greeks in the 2nd-1st century BC in Mathura down to 70 or 69 BC.[72] On the contrary, the Sungas, are thought to have been absent from Mathura, as no epigraphical remains or coins have been found, and to have been based to the east of the Mathura region.[72]

Stone art and architecture began being produced at Mathura at the time of "Indo-Greek hegemony" over the region.[75][50] Some authors consider that Indo-Greek cultural elements are not particularly visible in these works, and Hellenistic influence is not more important than in other parts of India.[51] Others consider that Hellenistic influence appears in the liveliness and the realistic details of the figures (an evolution compared to the stiffness of Mauryan art), the use of perspective from 150 BCE, iconographical details such as the knot and the club of Heracles, the wavy folds of the dresses, or the depiction of bacchanalian scenes:[50][52]

"Mathura sculpture is distinguished by several qualitative features of art, culture and religious history. The geographical position of the city on the highway leading from the Madhyadesa towards Madra-Gandhara contributed in a large measure to the eclectic nature of its culture. Mathura became the meeting ground of the traditions of the early Indian art of Bharhut and Sanchi together with strong influences of the Iranian and the Indo-Bactrian or the Gandhara art from the North-West. The Persepolitan capitals with human-headed animal figures and volutes as well as the presence of the battlement motif as a decorative element point to Iranian affinities. These influences came partly as a result of the general saturation of foreign motifs in early Indian sculpture as found in the Stupas of Bharhut and Sanchi also."

— Vasudeva Shrarana Agrawala, Masterpieces of Mathura sculpture[76]

The art of Mathura became extremely influential over the rest of India, and was "the most prominent artistic production center from the second century BCE".[50]

Colossal anthropomorphic statues (2nd century BCE)

Yakshas seems to have been the object of an important cult in the early periods of Indian history, many of them being known such as Kubera, king of the Yakshas, Manibhadra or Mudgarpani.[77] The Yakshas are a broad class of nature-spirits, usually benevolent, but sometimes mischievous or capricious, connected with water, fertility, trees, the forest, treasure and wilderness,[78][79] and were the object of popular worship.[80] Many of them were later incorporated into Buddhism, Jainism or Hinduism.[77]

In the 2nd century BCE, Yakshas became the focus of the creation of colossal cultic images, typically around 2 meters or more in height, which are considered as probably the first Indian anthropomorphic productions in stone.[52][77] Although few ancient Yaksha statues remains in good condition, the vigor of the style has been applauded, and expresses essentially Indian qualities.[52] They are often pot-bellied, two-armed and fierce-looking.[77] The Yashas are often depicted with weapons or attributes, such as the Yaksha Mudgarpani who in the right hand holds a mudgar mace, and in the left hand the figure of a small standing devotee or child joining hands in prayer.[70][77] It is often suggested that the style of the colossal Yaksha statuary had an important influence on the creation of later divine images and human figures in India.[81] The female equivalent of the Yashas were the Yashinis, often associated with trees and children, and whose voluptuous figures became omnipresent in Indian art.[77]

Some Hellenistic influence, such as the geometrical folds of the drapery or the walking stance of the statues, has been suggested.[52] According to John Boardman, the hem of the dress in the monumental early Yaksha statues is derived from Greek art.[52] Describing the drapery of one of these statues, John Boardman writes: "It has no local antecedents and looks most like a Greek Late Archaic mannerism", and suggests it is possibly derived from the Hellenistic art of nearby Bactria where this design is known.[52]

In the production of colossal Yaksha statues carved in the round, which can be found in several locations in northern India, the art of Mathura is considered as the most advanced in quality and quantity during this period.[82] Colossal Nāga statues are also known from this period in Mathura, also denoting an early cult of this deity.[83]

Incipient Greco-Buddhist art

The possibility of a direct connection between the Indo-Greeks and Greco-Buddhist art has been reaffirmed recently as the dating of the rule of Indo-Greek kings has been extended to the first decades of the 1st century CE, with the reign of Strato II in the Punjab.[84] Also, Foucher, Tarn and more recently Boardman, Bussagli or McEvilley have taken the view that some of the most purely Hellenistic works of northwestern India, Pakistan and Afghanistan, may actually be wrongly attributed to later centuries, and instead belong to a period one or two centuries earlier, to the time of the Indo-Greeks in the 2nd-1st century BCE:[85]

This is particularly the case of some purely Hellenistic works in Hadda, Afghanistan, an area which "might indeed be the cradle of incipient Buddhist sculpture in Indo-Greek style".[86] Referring to one of the Buddha triads in Hadda (drawing), in which the Buddha is sided by very Classical depictions of Herakles/Vajrapani and Tyche/Hariti, Boardman explains that both figures "might at first (and even second) glance, pass as, say, from Asia Minor or Syria of the first or second century BC (...) these are essentially Greek figures, executed by artists fully conversant with far more than the externals of the Classical style".[87] Many of the works of art at Hadda can also be compared to the style of the 2nd century BCE sculptures of the Hellenistic world, such as those of the Temple of Olympia at Bassae in Greece, which could also suggest roughly contemporary dates.

Alternatively, it has been suggested that these works of art may have been executed by itinerant Greek artists during the time of maritime contacts with the West from the 1st to the 3rd century CE.[88]

The supposition that such highly Hellenistic and, at the same time Buddhist, works of art belong to the Indo-Greek period would be consistent with the known Buddhist activity of the Indo-Greeks (the Milinda Panha etc...), their Hellenistic cultural heritage which would naturally have induced them to produce extensive statuary, their know artistic proficiency as seen on their coins until around 50 BCE, and the dated appearance of already complex iconography incorporating Hellenistic sculptural codes with the Bimaran casket in the early 1st century CE.

Greek-looking people in the art of Gandhara

The Greco-Buddhist art of Gandhara, beyond the omnipresence of Greek style and stylistic elements which might be simply considered as an enduring artistic tradition,[89] offers numerous depictions of people in Greek Classical realistic style, attitudes and fashion (clothes such as the chiton and the himation, similar in form and style to the 2nd century BCE Greco-Bactrian statues of Ai-Khanoum, hairstyle), holding contraptions which are characteristic of Greek culture (amphoras, "kantaros" Greek drinking cups), in situations which can range from festive (such as Bacchanalian scenes) to Buddhist-devotional.[90][91]

Uncertainties in dating make it unclear whether these works of art actually depict Greeks of the period of Indo-Greek rule up to the 1st century BCE, or remaining Greek communities under the rule of the Indo-Parthians or Kushans in the 1st and 2nd century CE.

Hellenistic groups

A series of reliefs, several of them known as the Buner reliefs which were taken during the 19th century from Buddhist structures near the area of Buner in northern Pakistan, depict in perfect Hellenistic style gatherings of people in Greek dress, socializing, drinking or playing music.[92] They have been called "Proto-Gandharan",[55] and are considered to be "slightly later" then the earliest stone palettes, themselves dated to circa 100 BCE.[55][46] Some other of these reliefs depict Indo-Scythian soldiers in uniform, sometimes playing instruments.[93] Finally, revelling Indian in dhotis richly adorned with jewelry are also shown. These are considered some of the most artistically perfect, and earliest, of Gandharan sculptures, and are thought to exalt multicultural interaction within the context of Buddhism, in the 1st century BCE or the 1st century CE.

Hellenistic drinking scene.

Hellenistic drinking scene. Hellenistic marine deities, Gandhara, 1st century.

Hellenistic marine deities, Gandhara, 1st century. Hellenistic drinking scene, Sar Khi Derri.

Hellenistic drinking scene, Sar Khi Derri. The Trojan Horse.

The Trojan Horse.

Bacchic scenes

Greeks harvesting grapes, Greeks drinking and revelling, scenes of erotical courtship are also numerous, and seem to relate to some of the most remarkable traits of Greek culture.[94] These reliefs also belong to Buddhist structures, and it is sometimes suggested that they might represent some kind of paradisical world after death.

Hellenistic devotees

Depictions of people in Hellenistic dress within a Buddhist context are also numerous.[95] Some show a Greek devotee couple circumambulating stupas together with shaven monks, others Greek protagonists are incorporated in Buddhist jataka stories of the life of the Buddha (relief of The Great Departure), others are simply depicted as devotees on the columns of Buddhist structures. A few famous friezes, including one in the British Museum, also depict the story of the Trojan horse. It is unclear whether these reliefs actually depict contemporary Greek devotees in the area of Gandhara, or if they are just part of a remaining artistic tradition. Most of these reliefs are usually dated to the 1st-3rd century CE.

Couple of devotees in Hellenistic himation dress, at the base of a Buddha statue.

Couple of devotees in Hellenistic himation dress, at the base of a Buddha statue. Devotee in Greek dress, on a Buddhist pilaster. Chakhil-i-Ghoundi Stupa.

Devotee in Greek dress, on a Buddhist pilaster. Chakhil-i-Ghoundi Stupa. "The Great Departure", with the Buddha amid Greek deities and costumes.

"The Great Departure", with the Buddha amid Greek deities and costumes. Hellenistic man or God, Gandhara.

Hellenistic man or God, Gandhara..jpg.webp) Indo-Corinthian capital representing a Buddhist devotee wearing a Greek cloak (chlamys) attached by a fibula. Dated to the 1st century BCE. Butkara Stupa.

Indo-Corinthian capital representing a Buddhist devotee wearing a Greek cloak (chlamys) attached by a fibula. Dated to the 1st century BCE. Butkara Stupa. Aristocratic women, Gandhara.

Aristocratic women, Gandhara.

Contributions by "Yavanas" in the 1st-2nd centuries CE

.jpg.webp)

After formal Greek political power waned circa 10 CE, some Greek nuclei may have continued to survive until the 2nd century AD.[97]

Tapa Shotor

According to archaeologist Raymond Allchin, the site of Tapa Shotor near Hadda suggests that the Greco-Buddhist art of Gandhara descended directly from the art of Hellenistic Bactria, as seen in Ai-Khanoum.[98] Archaeologist Zemaryalai Tarzi has suggested that, following the fall of the Greco-Bactrian cities of Ai-Khanoum and Takht-i Sangin, Greek populations were established in the plains of Jalalabad, which included Hadda, around the Hellenistic city of Dionysopolis, and that they were responsible for the Hellenistic Buddhist creations of Tapa Shotor in the 2nd century CE.[96]

Buddhist caves

A large number of Buddhist caves in India, particularly in the west of the country, were artistically hewn between the 1st century BC and the 2nd century CE. Numerous donors provided the funds for the building of these caves and left donatory inscriptions, including laity, members of the clergy, government officials. Foreigners, mostly self-declared Yavanas, represented about 8% of all inscriptions.[99]

Karla Caves

Yavanas from the region of Nashik are mentioned as donors for six structural pillars in the Great Buddhist Chaitya of the Karla Caves built and dedicated by Western Satraps ruler Nahapana in 120 CE,[101] although they seem to have adopted Buddhist names.[102] In total, the Yavanas account for nearly half of the known dedicatory inscriptions on the pillars of the Great Chaitya.[103] To this day, Nasik is known as the wine capital of India, using grapes that were probably originally imported by the Greeks.[104]

Shivneri Caves

Two more Buddhist inscriptions by Yavanas were found in the Shivneri Caves.[105] One of the inscriptions mentions the donation of a tank by the Yavana named Irila, while the other mentions the gift of a refectory to the Sangha by the Yavana named Cita.[105] On this second inscription, the Buddhist symbols of the triratna and of the swastika (reversed) are positioned on both sides of the first word "Yavana(sa)".

Pandavleni Caves

One of the Buddhist caves (Cave No.17) in the Pandavleni Caves complex near Nashik was built and dedicated by "Indragnidatta the son of the Yavana Dharmadeva, a northerner from Dattamittri", in the 2nd century AD.[106][107][108] The city of "Dattamittri" is thought to be the city of Demetrias in Arachosia, mentioned by Isidore of Charax.[106]

Manmodi Caves

In the Manmodi Caves, near Junnar, an inscription by a Yavana donor appears on the façade of the main Chaitya, on the central flat surface of the lotus over the entrance: it mentions the erection of the hall-front (façade) for the Buddhist Samgha, by a Yavana donor named Chanda:[109]

"yavanasa camdānam gabhadā[ra]"

"The meritorious gift of the façade of the (gharba) hall by the Yavana Chanda"

These contributions seem to have ended when the Satavahana King Gautamiputra Satakarni claimed to have vanquished a confederacy of Yavanas (Indo-Greeks), Shakas (Western Kshatrapas), Pahlavas (Indo-Parthians) under the Western Satrap ruler Nahapana circa 130 CE. This victory is known from the fact that Gautamiputra Satakarni restruck many of Nahapana's coins, and that he is claimed to have defeated the Yavanas and their confederates in the inscription of his mother Queen Gotami Balasiri at Cave No. 3 of the Nasik Caves:[113][114]

...Siri-Satakani Gotamiputa (....) who crushed down the pride and conceit of the Kshatriyas; who destroyed the Sakas, Yavanas and Palhavas; who rooted out the Khakharata race; who restored the glory of the Satavahana family...

See also

Notes

- 1 2 Holt, Frank Lee (1988). Alexander the Great and Bactria: The Formation of a Greek Frontier in Central Asia. Brill Archive. ISBN 9004086129.

- 1 2 3 Thapar, Romila (2004). Early India: From the Origins to AD 1300. University of California Press. pp. 215–216. ISBN 9780520242258.

- ↑ "The extraordinary realism of their portraiture. The portraits of Demetrius, Antimachus and of Eucratides are among the most remarkable that have come down to us from antiquity" Hellenism in ancient India, Banerjee, p134

- ↑ "Just as the Frank Clovis had no part in the development of Gallo-Roman art, the Indo-Scythian Kanishka had no direct influence on that of Indo-Greek Art; and besides, we have now the certain proofs that during his reign this art was already stereotyped, if not decadent" Hellenism in Ancient India, Banerjee, p147

- ↑ "The survival into the first century AD of a Greek administration and presumably some elements of Greek culture in the Punjab has now to be taken into account in any discussion of the role of Greek influence in the development of Gandharan sculpture", in Cribb, Joe; Bopearachchi, Osmund (1992). The Crossroads of Asia: transformation in image and symbol in the art of ancient Afghanistan and Pakistan. Cambridge: Fitzwilliam Museum, Ancient India and Iran Trust. p. 14. ISBN 9780951839911.

- ↑ "Following discoveries at Ai-Khanum, in modern-day Afghanistan excavations at Tapa Shotor, Hadda, produced evidence to indicate that Gandharan art descended directly from Hellenised Bactrian art." in Allchin, Frank Raymond (1997). Gandharan Art in Context: East-west Exchanges at the Crossroads of Asia. Published for the Ancient India and Iran Trust, Cambridge by Regency Publications. p. 19. ISBN 9788186030486.

- ↑ "We have to look for the beginnings of Gandharan Buddhist art both in the residual Indo-Greek tradition, and in the early Buddhist stone sculpture to the South (Bharhut etc...)" in Boardman, John (1994). The Diffusion of Classical Art in Antiquity. Princeton University Press. p. 124. ISBN 9780691036809.

- ↑ "Bopearachchi attributes the destruction of Ai Khanoum to the Yuezhi, rather than to the alternative 'conquerors' and destroyers of the last vestiges of Greek power in Bactria, the Sakas..." Benjamin, Craig (2007). The Yuezhi: Origin, Migration and the Conquest of Northern Bactria. Isd. p. 180. ISBN 9782503524290.

- 1 2 Singh, Upinder (2008). A History of Ancient and Early Medieval India: From the Stone Age to the 12th Century. Pearson Education India. p. 373. ISBN 9788131716779.

- ↑ Holt, Frank Lee (1999). Thundering Zeus: the making of Hellenistic Bactria. University of California Press. pp. 135–136. ISBN 9780520920095.

- ↑ Joseph, Frances A.M. (2016). Conflict in Ancient Greece and Rome: The Definitive Political, Social, and Military Encyclopedia [3 volumes]: The Definitive Political, Social, and Military Encyclopedia. ABC-CLIO. pp. 239–240. ISBN 9781610690201.

- ↑ Cohen, Getzel M. (2013). The Hellenistic Settlements in the East from Armenia and Mesopotamia to Bactria and India. University of California Press. p. 242. ISBN 9780520953567.

- ↑ Gyselen, Rika (2007). Des Indo-Grecs aux Sassanides: données pour l'histoire et la géographie historique. Peeters Publishers. p. 104. ISBN 9782952137614.

- ↑ Yarshater, Ehsan (1983). The Cambridge History of Iran. Cambridge University Press. p. 190. ISBN 9780521200929.

- ↑ Baumer, Christoph (2012). The History of Central Asia: The Age of the Steppe Warriors. I.B.Tauris. p. 289. ISBN 9781780760605.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Singh, Upinder (2008). A History of Ancient and Early Medieval India: From the Stone Age to the 12th Century. Pearson Education India. p. 374. ISBN 9788131716779.

- ↑ Behrendt, Kurt A. (2007). The Art of Gandhara in the Metropolitan Museum of Art. Metropolitan Museum of Art. p. 7. ISBN 9781588392244.

- ↑ "It has all the hallmarks of a Hellenistic city, with a Greek theatre, gymnasium and some Greek houses with colonnaded courtyards" (Boardman).

- 1 2 Singh, Upinder (2008). A History of Ancient and Early Medieval India: From the Stone Age to the 12th Century. Pearson Education India. p. 375. ISBN 9788131716779.

- 1 2 3 Holt, Frank Lee (1999). Thundering Zeus: The Making of Hellenistic Bactria. University of California Press. pp. 43–44. ISBN 9780520920095.

- ↑ Bernard, Paul (1967). "Deuxième campagne de fouilles d'Aï Khanoum en Bactriane". Comptes rendus des séances de l'Académie des Inscriptions et Belles-Lettres. 111 (2): 306–324. doi:10.3406/crai.1967.12124.

- ↑ Source, BBC News, Another article. German story with photographs here (translation here).

- ↑ Demetrius is said to have founded Taxila (archaeological excavations), and also Sagala in the modern-day Pakistan, which he seemed to have called Euthydemia, after his father ("the city of Sagala, also called Euthydemia" (Ptolemy, Geographia, VII 1))

- ↑ A Journey Through India's Past Chandra Mauli Mani, Northern Book Centre, 2005, p. 39

- ↑ MacDowall, 2004

- ↑ "The only thing that seems reasonably sure is that Taxila was part of the domain of Agathocles", Bopearachchi, Monnaies, p. 59

- ↑ Krishan, Yuvraj; Tadikonda, Kalpana K. (1996). The Buddha Image: Its Origin and Development. Bharatiya Vidya Bhavan. p. 22. ISBN 9788121505659.

- 1 2 Iconography of Balarāma, Nilakanth Purushottam Joshi, Abhinav Publications, 1979, p. 22

- 1 2 Stanton, Andrea L.; Ramsamy, Edward; Seybolt, Peter J.; Elliott, Carolyn M. (2012). Cultural Sociology of the Middle East, Asia, and Africa: An Encyclopedia. SAGE Publications. p. 28. ISBN 9781452266626.

- 1 2 Singh, Nagendra Kr; Mishra, A. P. (2007). Encyclopaedia of Oriental Philosophy and Religion: Buddhism. Global Vision Publishing House. pp. 351, 608–609. ISBN 9788182201156.

- ↑ "Afghanistan, tresors retrouves", p150

- ↑ Joe Cribb, Investigating the introduction of coinage in India, Journal of the Numismatic Society of India xlv Varanasi 1983 pp.89

- ↑ Ghosh, Amalananda (1965). Taxila. CUP Archive. p. 763.

- ↑ McNicoll, Anthony; Milner, N. P. (1997). Hellenistic Fortifications from the Aegean to the Euphrates. Clarendon Press. p. 102. ISBN 9780198132288.

- ↑ "Menander". Encyclopædia Britannica Online. Encyclopædia Britannica, Inc. Retrieved 7 August 2015.

Menander, also spelled Minedra or Menadra, Pali Milinda (flourished 160 BCE?–135 BCE?), the greatest of the Indo-Greek kings and the one best known to Western and Indian classical authors. He is believed to have been a patron of the Buddhist religion and the subject of an important Buddhist work, the Milinda-panha ("The Questions of Milinda"). Menander was born in the Caucasus, but the Greek biographer Plutarch calls him a king of Bactria, and the Greek geographer and historian Strabo includes him among the Bactrian Greeks "who conquered more tribes than Alexander [the Great]."

- ↑ Osmund Bopearachchi, 2016, Emergence of Viṣṇu and Śiva Images in India: Numismatic and Sculptural Evidence

- ↑ Hermann Kulke and Dietmar Rothermund (2004). A History of India. Routledge. p. 73. ISBN 978-0-415-32920-0.

- 1 2 Gallieri, Pier Francesco (2007). On the Cusp of an Era: Art in the Pre-Kuṣāṇa World. BRILL. pp. 140–150. ISBN 9789004154513.

- ↑ Khaliq, Fazal (24 May 2015). "Swat's archaeological sites: a victim of neglect". DAWN.COM. Retrieved 2017-09-13.

- ↑ Ancient Indian History and Civilization, Sailendra Nath Sen, New Age International, 1999 p. 170

- ↑ Handbuch der Orientalistik, Kurt A. Behrendt, BRILL, 2004, p.49 sig

- ↑ "King Menander, who built the penultimate layer of the Butkara stupa in the first century BCE, was an Indo-Greek." Empires of the Indus: The Story of a River, Alice Albinia, 2012

- ↑ Avari, Burjor (2016). India: The Ancient Past: A History of the Indian Subcontinent from C. 7000 BCE to CE 1200. Routledge. p. 167. ISBN 9781317236733.

- 1 2 Baums, Stefan (2017). A framework for Gandharan chronology based on relic inscriptions, in "Problems of Chronology in Gandharan Art". Archaeopress.

- ↑ Marshall, John (1951). Taxila vol.III. p. Plaque 144.

- 1 2 Siudmak, John (2013). The Hindu-Buddhist Sculpture of Ancient Kashmir and its Influences. BRILL. pp. 58–59. ISBN 978-90-04-24832-8.

- ↑ Siudmak, John (2013). The Hindu-Buddhist Sculpture of Ancient Kashmir and its Influences. BRILL. p. 57 note 65. ISBN 978-90-04-24832-8.

- ↑ Rapson, Edward James (1922). The Cambridge history of India. Cambridge University Press.

- ↑ History of Early Stone Sculpture at Mathura: Ca. 150 BCE - 100 CE, Sonya Rhie Quintanilla, BRILL, 2007 pp. 254-255

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 Stoneman, Richard (2019). The Greek Experience of India: From Alexander to the Indo-Greeks. Princeton University Press. pp. 436–437. ISBN 9780691185385.

- 1 2 Quintanilla, Sonya Rhie (2007). History of Early Stone Sculpture at Mathura: Ca. 150 BCE - 100 CE. BRILL. p. 10. ISBN 9789004155374.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 Boardman, John (1993). The Diffusion of Classical Art in Antiquity. Princeton University Press. p. 112. ISBN 0691036802.

- ↑ Jamwal, Suman (1994). "Commercial Contacts Between Kashmir and Rome". Annals of the Bhandarkar Oriental Research Institute. 75 (1/4): 202. ISSN 0378-1143. JSTOR 41694416.

- 1 2 Siudmak, John (2013). The Hindu-Buddhist Sculpture of Ancient Kashmir and its Influences. BRILL. pp. 32–36. ISBN 978-90-04-24832-8.

- 1 2 3 Siudmak, John (2013). The Hindu-Buddhist Sculpture of Ancient Kashmir and its Influences. BRILL. p. 43. ISBN 978-90-04-24832-8.

- ↑ Kaw, Mushtaq A. (2010). "Central Asian Contribution to Kashmir's Tradition of Religio-Cultural Pluralism". Central Asiatic Journal. 54 (2): 245. ISSN 0008-9192. JSTOR 41928559.

- ↑ Siudmak, John (2013). The Hindu-Buddhist Sculpture of Ancient Kashmir and its Influences. BRILL. pp. 39–43. ISBN 978-90-04-24832-8.

- 1 2 3 4 Falk, Harry (2015). Buddhistische Reliquienbehälter aus der Sammlung Gritli von Mitterwallner. pp. 134–135.

- ↑ Salomon, Richard (2005). A New Inscription dated in the "Yona" (Greek) Era of 186/5 B.C. Brepols. pp. 359–400. ISBN 978-2-503-51681-3.

- ↑ Chakravarti, N. P (1937). Epigraphia Indica Vol.24. pp. 1–10.

- ↑ Fussman, 1986, p.71, quoted in The Crossroads of Asia, p.192

- ↑ The Cambridge History of India. CUP Archive. 1922. pp. 646–647.

- ↑ Quintanilla, Sonya Rhie (2007). History of Early Stone Sculpture at Mathura: Ca. 150 BCE - 100 CE. BRILL. p. 132 Note 57. ISBN 9789004155374.

- ↑ BOARDMAN, JOHN (1998). "Reflections on the Origins of Indian Stone Architecture". Bulletin of the Asia Institute. 12: 13–22. ISSN 0890-4464. JSTOR 24049089.

- ↑ Dated 150 BCE in Fig. 15-17, general comments p.26-27 in Quintanilla, Sonya Rhie (2007). History of Early Stone Sculpture at Mathura: Ca. 150 BCE - 100 CE. BRILL. ISBN 9789004155374.

- ↑ Dated 100 BCE in Fig.88 in Quintanilla, Sonya Rhie (2007). History of Early Stone Sculpture at Mathura: Ca. 150 BCE - 100 CE. BRILL. p. 368, Fig. 88. ISBN 9789004155374.

- 1 2 Dated 100 BCE in Fig. 86-87, page 365-368 in Quintanilla, Sonya Rhie (2007). History of Early Stone Sculpture at Mathura: Ca. 150 BCE - 100 CE. BRILL. p. Fig.85, p.365. ISBN 9789004155374.

- 1 2 Dated 150 BCE in Fig. 20, page 33-35 in Quintanilla, Sonya Rhie (2007). History of Early Stone Sculpture at Mathura: Ca. 150 BCE - 100 CE. BRILL. p. Fig.85, p.365. ISBN 9789004155374.

- ↑ Quintanilla, Sonya Rhie (2007). History of Early Stone Sculpture at Mathura: Ca. 150 BCE - 100 CE. BRILL. p. 368, Fig. 88. ISBN 9789004155374.

- 1 2 Fig. 85 in Quintanilla, Sonya Rhie (2007). History of Early Stone Sculpture at Mathura: Ca. 150 BCE - 100 CE. BRILL. p. Fig.85, p.365. ISBN 9789004155374.

- ↑ Dalal, Roshen (2010). The Religions of India: A Concise Guide to Nine Major Faiths. Penguin Books India. p. 398. ISBN 978-0-14-341517-6.

- 1 2 3 Quintanilla, Sonya Rhie (2007). History of Early Stone Sculpture at Mathura: Ca. 150 BCE - 100 CE. BRILL. pp. 8–10. ISBN 978-90-04-15537-4.

- ↑ Published in "L'Indo-Grec Menandre ou Paul Demieville revisite," Journal Asiatique 281 (1993) p.113

- ↑ "Some Newly Discovered Inscriptions from Mathura : The Meghera Well Stone Inscription of Yavanarajya Year 160 Recently a stone inscription was acquired in the Government Museum, Mathura." India's ancient past, Shankar Goyal Book Enclave, 2004, p.189

- ↑ "During the time of Indo-Greek hegemony, art and architecture in the medium of stone began to be produced in the Mathura region" in Quintanilla, Sonya Rhie (2007). History of Early Stone Sculpture at Mathura: Ca. 150 BCE - 100 CE. BRILL. p. 10. ISBN 978-90-04-15537-4.

- ↑ Agrawala, Vasudeva S. (1965). Masterpieces of Mathura sculpture. p. 3.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Dalal, Roshen (2010). The Religions of India: A Concise Guide to Nine Major Faiths. Penguin Books India. pp. 397–398. ISBN 978-0-14-341517-6.

- ↑ Singh, Upinder (2008). A History of Ancient and Early Medieval India. New Delhi: Pearson Education. p. 430. ISBN 978-81-317-1120-0.

- ↑ "yaksha". Encyclopædia Britannica. Retrieved 15 July 2007.

- ↑ Sharma, Ramesh Chandra (1994). The Splendour of Mathurā Art and Museum. D.K. Printworld. p. 76. ISBN 978-81-246-0015-3.

- ↑ "The folk art typifies an older plastic tradition in clay and wood which was now put in stone, as seen in the massive Yaksha statuary which are also of exceptional value as models of subsequent divine images and human figures." in Agrawala, Vasudeva Sharana (1965). Indian Art: A history of Indian art from the earliest times up to the third century A. D. Prithivi Prakashan. p. 84.

- ↑ "With respect to large-scale iconic statuary carved in the round (...) the region of Mathura not only rivaled other areas but surpassed them in overall quality and quantity throughout the second and early first century BCE." in Quintanilla, Sonya Rhie (2007). History of Early Stone Sculpture at Mathura: Ca. 150 BCE - 100 CE. BRILL. p. 24. ISBN 9789004155374.

- ↑ Dated 150 BCE in Fig.20 in Quintanilla, Sonya Rhie (2007). History of Early Stone Sculpture at Mathura: Ca. 150 BCE - 100 CE. BRILL. ISBN 9789004155374.

- ↑ "The survival into the 1st century AD of a Greek administration and presumably some elements of Greek culture in the Punjab has now to be taken into account in any discussion of the role of Greek influence in the development of Gandharan sculpture", The Crossroads of Asia, p. 14

- ↑ On the Indo-Greeks and the Gandhara school:

- 1) "It is necessary to considerably push back the start of Gandharan art, to the first half of the first century BCE, or even, very probably, to the preceding century.(...) The origins of Gandharan art... go back to the Greek presence. (...) Gandharan iconography was already fully formed before, or at least at the very beginning of our era" Mario Bussagli "L'art du Gandhara", p331–332

- 2) "The beginnings of the Gandhara school have been dated everywhere from the first century B.C. (which was M. Foucher's view) to the Kushan period and even after it" (Tarn, p394). Foucher's views can be found in "La vieille route de l'Inde, de Bactres a Taxila", pp340–341). The view is also supported by Sir John Marshall ("The Buddhist art of Gandhara", pp5–6).

- 3) Also the recent discoveries at Ai-Khanoum confirm that "Gandharan art descended directly from Hellenized Bactrian art" (Chaibi Nustamandy, "Crossroads of Asia", 1992).

- 4) On the Indo-Greeks and Greco-Buddhist art: "It was about this time (100 BCE) that something took place which is without parallel in Hellenistic history: Greeks of themselves placed their artistic skill at the service of a foreign religion, and created for it a new form of expression in art" (Tarn, p393). "We have to look for the beginnings of Gandharan Buddhist art in the residual Indo-Greek tradition, and in the early Buddhist stone sculpture to the South (Bharhut etc.)" (Boardman, 1993, p124). "Depending on how the dates are worked out, the spread of Gandhari Buddhism to the north may have been stimulated by Menander's royal patronage, as may the development and spread of the Gandharan sculpture, which seems to have accompanied it" McEvilley, 2002, "The shape of ancient thought", p378.

- ↑ Boardman, p141

- ↑ Boardman, p143

- ↑ "Others, dating the work to the first two centuries A.D., after the waning of Greek autonomy on the Northwest, connect it instead with the Roman Imperial trade, which was just then getting a foothold at sites like Barbaricum (modern Karachi) at the Indus-mouth. It has been proposed that one of the embassies from Indian kings to Roman emperors may have brought back a master sculptorto oversee work in the emerging Mahayana Buddhist sensibility (in which the Buddha came to be seen as a kind of deity), and that "bands of foreign workmen from the eastern centers of the Roman Empire" were brought to India" (Mc Evilley "The shape of ancient thought", quoting Benjamin Rowland "The art and architecture of India" p121 and A.C. Soper "The Roman Style in Gandhara" American Journal of Archaeology 55 (1951) pp301–319)

- ↑ Boardman, p.115

- ↑ McEvilley, p.388-390

- ↑ Boardman, 109-153

- ↑ Boardman, p.126

- ↑ Marshall, "The Buddhist art of Gandhara", p.36

- ↑ "At the time, a favourite theme of Graeco-Parthian secular art was the drinking scene, and incongruous as it may seem, this was one of the earliest themes to be adopted for the decoration of Buddhist stupas." Marshall, p.33

- ↑ Marshall, p.33-39

- 1 2 Tarzi, Zémaryalai (2001). "Le site ruiné de Hadda". Afghanistan, patrimoine en péril: actes d'une journée d'étude. CEREDAF. p. 63 – via HAL open science.

- ↑ Wallace, Shane (2016). "Greek Culture in Afghanistan and India: Old Evidence and New Discoveries". Greece and Rome. 63 (2): 205–226, 210. doi:10.1017/S0017383516000073. S2CID 163916645.

- ↑ "Following discoveries at Ai-Khanum, excavations at Tapa Shotor, Hadda, produced evidence to indicate that Gandharan art descended directly from Hellenised Bactrian art. It is quite clear from the clay figure finds in particular , that either Bactrian artist from the north were placed at the service of Buddhism, or local artists, fully conversant with the style and traditions of Hellenistic art , were the creators of these art objects" in Allchin, Frank Raymond (1997). Gandharan Art in Context: East-west Exchanges at the Crossroads of Asia. Published for the Ancient India and Iran Trust, Cambridge by Regency Publications. p. 19. ISBN 9788186030486.

- ↑ Buddhist architecture, Lee Huu Phuoc, Grafikol 2009, pp. 98–99

- ↑ Epigraphia Indica Vol.18 p. 328 Inscription No10

- ↑ World Heritage Monuments and Related Edifices in India, Volume 1 ʻAlī Jāvīd, Tabassum Javeed, Algora Publishing, 2008 p. 42

- ↑

- Inscription no.7: "(This) pillar (is) the gift of the Yavana Sihadhaya from Dhenukataka" in Problems of Ancient Indian History: New Perspectives and Perceptions, Shankar Goyal - 2001, p. 104

* Inscription no.4: "(This) pillar (is) the gift of the Yavana Dhammadhya from Dhenukataka"

Description in Hellenism in Ancient India by Gauranga Nath Banerjee p. 20

- Inscription no.7: "(This) pillar (is) the gift of the Yavana Sihadhaya from Dhenukataka" in Problems of Ancient Indian History: New Perspectives and Perceptions, Shankar Goyal - 2001, p. 104

- ↑ Epigraphia Indica Vol.18 pp. 326–328 and Epigraphia Indica Vol.7 [Epigraphia Indica Vol.7 pp. 53–54

- ↑ Philpott, Don (2016). The World of Wine and Food: A Guide to Varieties, Tastes, History, and Pairings. Rowman & Littlefield. p. 133. ISBN 9781442268043.

- 1 2 The Greek-Indians of Western India: A Study of the Yavana and Yonaka Buddhist Cave Temple Inscriptions, 'The Indian International Journal of Buddhist Studies', NS 1 (1999-2000) S._1_1999-2000_pp._83-109 p. 87–88

- 1 2 Epigraphia Indica p. 90ff

- ↑ Hellenism in Ancient India, Gauranga Nath Banerjee p. 20

- ↑ The Roman Empire and the Indian Ocean: The Ancient World Economy and the Kingdoms of Africa, Arabia and India, Raoul McLaughlin, Pen and Sword, 2014 p. 170

- ↑ Religions and Trade: Religious Formation, Transformation and Cross-Cultural Exchange between East and West. BRILL. 2013. p. 97, note 97. ISBN 9789004255302.

- ↑ Journal of the Epigraphical Society of India. The Society. 1994. pp. iv.

- ↑ Archaeological Survey of Western India. Government Central Press. 1879. pp. 43–44.

- ↑ Karttunen, Klaus (2015). "Yonas and Yavanas In Indian Literature". Studia Orientalia. 116: 214.

- ↑ Upinder Singh (2008). A History of Ancient and Early Medieval India: From the Stone Age to the 12th Century. Pearson Education India. ISBN 978-81-317-1120-0. p. 383

- ↑ Nasik cave inscription No 1. "( Of him) the Kshatriya , who flaming like the god of love, subdued the Sakas, Yavavas and Palhavas" in Parsis of ancient India by Hodivala, Shapurji Kavasji p. 16

- ↑ Epigraphia Indica pp. 61–62

References

- Bopearachchi, Osmund (1991). Monnaies Gréco-Bactriennes et Indo-Grecques, Catalogue Raisonné (in French). Bibliothèque Nationale de France. ISBN 2-7177-1825-7.

- Avari, Burjor (2007). India: The ancient past. Routledge. ISBN 978-0415356169.

- Faccenna, Domenico (1980). Butkara I (Swāt, Pakistan) 1956–1962, Volume III 1. Rome: IsMEO (Istituto Italiano Per Il Medio Ed Estremo Oriente).

- McEvilley, Thomas (2002). The Shape of Ancient Thought. Comparative studies in Greek and Indian Philosophies. Allworth Press and the School of Visual Arts. ISBN 1-58115-203-5.

- Puri, Baij Nath (2000). Buddhism in Central Asia. Delhi: Motilal Banarsidass. ISBN 81-208-0372-8.

- Tarn, W. W. (1984). The Greeks in Bactria and India. Chicago: Ares. ISBN 0-89005-524-6.

- A.K. Narain, A.K. (2003). The Indo-Greeks. B.R. Publishing Corporation. "revised and supplemented" from Oxford University Press edition of 1957.

- A.K. Narain, A.K. (1976). The coin types of the Indo-Greeks kings. Chicago, USA: Ares Publishing. ISBN 0-89005-109-7.

- Cambon, Pierre (2007). Afghanistan, les trésors retrouvés (in French). Musée Guimet. ISBN 9782711852185.

- Keown, Damien (2003). A Dictionary of Buddhism. New York: Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-860560-9.

- Bopearachchi, Osmund (2003). De l'Indus à l'Oxus, Archéologie de l'Asie Centrale (in French). Lattes: Association imago-musée de Lattes. ISBN 2-9516679-2-2.

- Boardman, John (1994). The Diffusion of Classical Art in Antiquity. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press. ISBN 0-691-03680-2.

- Errington, Elizabeth; Cribb, Joe; Claringbull, Maggie; Ancient India and Iran Trust; Fitzwilliam Museum (1992). The Crossroads of Asia: transformation in image and symbol in the art of ancient Afghanistan and Pakistan. Cambridge: Ancient India and Iran Trust. ISBN 0-9518399-1-8.

- Bopearachchi, Osmund; Smithsonian Institution; National Numismatic Collection (U.S.) (1993). Indo-Greek, Indo-Scythian and Indo-Parthian coins in the Smithsonian Institution. Washington: National Numismatic Collection, Smithsonian Institution. OCLC 36240864.

- Alexander the Great: East-West cultural contacts from Greece to Japan. Tokyo: Tokyo National Museum. 2003. OCLC 53886263.

- Lowenstein, Tom (2002). The vision of the Buddha: Buddhism, the path to spiritual enlightenment. London: Duncan Baird. ISBN 1-903296-91-9.

- Foltz, Richard (2000). Religions of the Silk Road: overland trade and cultural exchange from antiquity to the fifteenth century. New York: St. Martin's Griffin. ISBN 0-312-23338-8.

- Marshall, Sir John Hubert (2000). The Buddhist art of Gandhara: the story of the early school, its birth, growth, and decline. New Delhi: Munshiram Manoharlal. ISBN 81-215-0967-X.

- Mitchiner, John E.; Garga (1986). The Yuga Purana: critically edited, with an English translation and a detailed introduction. Calcutta, India: Asiatic Society. ISBN 81-7236-124-6. OCLC 15211914.

- Salomon, Richard. "The "Avaca" Inscription and the Origin of the Vikrama Era". Vol. 102.

- Banerjee, Gauranga Nath (1961). Hellenism in ancient India. Delhi: Munshi Ram Manohar Lal. ISBN 0-8364-2910-9. OCLC 1837954.

- Bussagli, Mario; Tissot, Francine; Arnal, Béatrice (1996). L'art du Gandhara (in French). Paris: Librairie générale française. ISBN 2-253-13055-9.

- Marshall, John (1956). Taxila. An illustrated account of archaeological excavations carried out at Taxila (3 volumes). Delhi: Motilal Banarsidass.

- Osmund Bopearachchi, ed. (2005). Afghanistan, ancien carrefour entre l'est et l'ouest (in French and English). Belgium: Brepols. ISBN 2503516815.

- Seldeslachts, E. (2004). "The end of the road for the Indo-Greeks?". Iranica Antica. 39: 249–296. doi:10.2143/IA.39.0.503898.

- Senior, R.C. (2006). Indo-Scythian coins and history. Volume IV. Classical Numismatic Group, Inc. ISBN 0-9709268-6-3.