Artemio Ricarte | |

|---|---|

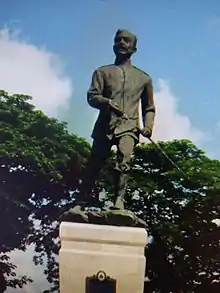

Ricarte in c. 1898 | |

| Commanding General of the Philippine Revolutionary Army | |

| In office 22 March 1897 – 22 January 1899 | |

| President | Emilio Aguinaldo |

| Preceded by | Office established |

| Succeeded by | Antonio Luna |

| Personal details | |

| Born | October 20, 1866 Batac, Ilocos Norte, Captaincy General of the Philippines, Spanish Empire |

| Died | July 31, 1945 (aged 78) Hungduan, Ifugao, Philippine Commonwealth |

| Cause of death | Dysentery |

| Nickname(s) | The Father of the Philippine Army Vibora (Viper) Father of the Overseas Filipino Workers |

| Military service | |

| Allegiance | (1896–1897) |

| Branch/service | |

| Years of service | 1896–1900 |

| Rank | |

| Battles/wars | Philippine Revolution |

Artemio Ricarte y García (October 20, 1866 – July 31, 1945) was a Filipino general during the Philippine Revolution and the Philippine–American War. He is regarded as the Father of the Philippine Army, and the first Chief of Staff of the Armed Forces of the Philippines (March 22, 1897- January 22, 1899) though the present Philippine Army descended from the American-allied forces that defeated the Philippine Revolutionary Army led by General Ricarte.[1] Ricarte is notable for never having taken an oath of allegiance to the United States government that occupied the Philippines from 1898 to 1946.

Early life

Artemio Ricarte was the middle child of Esteban Ricarte y Faustino and Bonifacia Garcia y Rigonan; the others were Uno and Ylumidad. They were all born in the town of Batac, Ilocos Norte. Artemio finished his early studies in his hometown and moved to Manila for his tertiary education. He enrolled at the Colegio de San Juan de Letran graduating with a Bachelor of Arts degree. He prepared for the teaching profession at the University of Santo Tomas and then at the Escuela Normal. After finishing his studies, he was sent to the town of San Francisco de Malabon (now General Trias) in Cavite to supervise a primary school. There, he met Mariano Álvarez, another school teacher and a surviving revolutionary of the 1872 Cavite mutiny. Ricarte joined the ranks of the Katipunan under the Magdiwang Council, where he held the rank of Lieutenant General.[2] He adopted the nom-de-guerre, "Víbora" (Viper).[3][4][5]

Philippine Revolution

After the start of the Philippine Revolution on August 31, 1896, Ricarte led the revolutionists in attacking the Spanish garrison in San Francisco de Malabon. He crushed the Spanish troops and took the civil guards prisoner. On March 22, 1897, during the Tejeros Convention, Ricarte was unanimously elected Captain-General of a new revolutionary government under Emilio Aguinaldo as president. While he took his oath of office alongside Aguinaldo, he at first joined the Katipunan leader Andres Bonifacio's protests against the legitimacy of this government alongside most other Magdiwang leaders, but he and the others abandoned Bonifacio within a month and he assumed his office in Aguinaldo's government on April 24. Later he received a military promotion to Brigadier-General in Aguinaldo's army.[6] He led his men in various battles in Cavite, Laguna, and Batangas. Aguinaldo designated him to remain in Biak-na-Bato, San Miguel, Bulacan to supervise the surrender of arms such that both the Spanish government and Aguinaldo's officers complied with the terms of the peace pact.

Philippine–American War

The second phase of the Philippine Revolution was ushered in when the Americans brought back Aguinaldo from exile on May 19, 1898. Ricarte was a minor figure at this stage. He was the rebel commander of Santa Ana when Manila fell to the combined Filipino-American forces on August 13, 1898. With the help of Rear Admiral George Dewey, commander of the American Asiatic Squadron anchored in Manila Bay, and General Wesley Merritt of the American Army, the Filipino troops routed the Spanish command of General Fermin Jaudenes. This eventually led General Jaudenes to surrender the City of Manila to Admiral Dewey, thus the liberation of the Philippines from the Spanish colonizers.

General Ricarte was jubilant over the victory, thinking it was the prelude to the attainment of complete Philippine independence. Unfortunately, however, the Americans afterwards refused to recognize the participation of the Filipinos in the siege of the city and even deprived them of their rights as victors to triumphantly enter its gates. The Americans, having gotten rid of the Spaniards with the help of Filipinos, were intent on possessing the Philippines. This development saddened Ricarte, to the extent that later on, he considered another option by which Filipinos could gain their independence.

When the Philippine–American War started in 1899, he was Chief of Operations of the Philippine forces in the third zone around Manila. In July 1900, he tried to infiltrate the American lines to enter Manila but he was captured by the Americans. For six months, he was locked up in the Bilibid Prisons but stubbornly refused to swear allegiance to the United States. Because of this, the Americans exiled him to Guam, together with many of the other rebel prisoners in the islands, termed Irreconcilables by them, including Apolinario Mabini. The exile lasted for two years.[5]

Post-war era

In early 1903, both Ricarte and Mabini would be allowed back into the Philippines upon taking the oath of allegiance to America.[7]: 546 Just as the United States Army Transport Thomas pulled into Manila Bay, both were asked to take the oath. Mabini, who was ill, took the oath but Ricarte refused. Ricarte was set free but banned from the Philippines. Without setting foot on Philippine soil, he was placed on the transport Garlic and sailed to Hong Kong.

On December 23, 1903, Ricarte arrived in the Philippines secretly as a stowaway in a freighter,[lower-alpha 1] planning to reunite with former members of the army and rekindle the Philippine Revolution.[9][10] Upon meeting with several former members and friends, he discussed his general plan and the continuation of the revolution. After said meetings, some of these members turned on Ricarte and notified the Americans, specifically former General Pío del Pilar. A reward for US$10,000 was then issued for Ricarte's capture, dead or alive. In the following weeks, Ricarte traveled throughout central Luzon trying to drum up support for his cause.

In early 1904, Ricarte was stricken by an illness that put him at rest for nearly two months. Just as his health was returning, a clerk from his outfit, Luis Baltazar, turned against him and notified the local Philippine Constabulary of his location at Mariveles, Bataan. In May 1904, Ricarte was arrested and spent the next six years at Bilibid Prison.[7]: 546 Ricarte was well received and respected by both the Philippine and American authorities. He was frequently visited by old friends from the Philippine revolutionary war as well as U.S. government officials, including the vice-president of the United States under Theodore Roosevelt, Charles W. Fairbanks.

Due to good behavior, Ricarte served only six years of his 11-year sentence. On June 26, 1910, he was released from Bilibid. But upon his exit he was detained by American authorities and taken to the Customs-House in Bagumbayan. He was again ordered to pledge his oath of allegiance to the United States. He still refused to swear allegiance and within the hour of the same day, he was again put on a transport and deported to Hong Kong.

From July 1, 1910 to 1915, Ricarte lived in Hong Kong, first on Lamma Island, at the mouth of the harbor, and, later in Kowloon where he initiated the publication of a fortnightly, "El Grito de Presente" (The Cry of the Present). His name was repeatedly brought to light whenever any manner of uprising occurred in the Philippines. To get away from damaging propaganda, he and his wife, together with his family moved to Tokyo and, later, to Yokohama, Japan, where he lived in self-exile at 149 Yamashita-cho. While in Japan, Ricarte and his wife, Agueda opened a small restaurant, Karihan Luvimin, and returned to teaching. They chose this name for it is so that Filipino travelers in Japan would know that there were Filipinos living there. Being an educator, Gen. Ricarte taught Spanish language at the Kaigai Shokumin Gakko School in Tokyo. To augment the family income, Agueda sold copies of her husband's book, "Hispano-Philippine Revolution", or Himagsikan nang manga Pilipino Laban sa Kastila (The Revolution of Filipinos Against the Spaniards) was published in Yokohama in 1927. It became very saleable to Filipinos on board ship.[3] Agueda Esteban, his wife engaged in the real estate business, which enabled the couple to purchase three houses in Japan.

In all the years they stayed in Japan, Ricarte's dream of an independent Philippines never waned. Every year, he never failed to celebrate Rizal Day and Bonifacio Day by hosting big affairs with Filipino residents and Japanese officials.

Wartime and Ricarte's return to the Philippines

Just as Ricarte's life was fading away into obscurity, World War II began and Imperial Japanese Army invaded the Philippines. In 1942, when Japan's military forces occupied Manila, Prime Minister Hideki Tojo asked Ricarte to return to the Philippines to help maintain peace and order. He agreed and requested Tojo to give Philippines its genuine independence from American colonial rule. Tojo thus promised Ricarte that if he could bring about peace and order in the Philippines within a year, the Japanese government would hand back to the Filipino people their independence. As he had always aspired to see a free Philippines, Ricarte accepted the offer. Under this agreement, he gained the respect of the Japanese and Filipino nationalists like Emilio Aguinaldo. In 1943, Japan nominally granted the Philippines independence with the establishment of the Second Philippine Republic, formally known as the "Republic of the Philippines", which in actuality was a puppet state of Japan.

Ricarte and Benigno Ramos

Sometime in November 1944, Gen. Artemio Ricarte informed his wife, Agueda that President Jose P. Laurel and his cabinet would have a meeting in Baguio with high-ranking Japanese officials and that he had to be present there. He would tell her further that in case he had to stay longer in Baguio, he would send for his family to join him.

Before he left Baguio, Benigno Ramos, the leader-founder of Makapili, invited him over to his place (now the site of Christ the King Church in Quezon City). He went there together with his granddaughter Ma. Luisa D. Fleetwood. While they were having their lunch, Ramos asked him to sign up as a member of the Makapili Organization. Gen. Ricarte, refused. He told Ramos that he did not have to sign up with the said organization in order to prove his patriotism and loyalty to his people. He added that he was already physically frail and could not carry out large tasks anymore. However, he gave the approval and blessing to establish the organization to counter the impending American invasion.

Death

Near the end of World War II, Ricarte again found himself taking flight from American and Filipino forces. Ricarte was implored by colleagues to evacuate the Philippines but had refused, stating "I can not take refuge in Japan at this critical moment when my people are in actual distress. I will stay in my Motherland to the last."

In 1945, Ricarte joined Japanese forces led by General Tomoyuki Yamashita in their flight to northern Luzon, where he was caught up in the Battle of Bessang Pass against the Philippine Commonwealth Army, Philippine Constabulary, and USAFIP-NL in Tagudin, Ilocos Sur. As the battle turned into an Allied victory, Ricarte fled further into the Cordillera mountains. He then fell ill from dysentery[11]: 167–168 and died on July 31, 1945, at the age of 78 in Hungduan, Ifugao. His grave was discovered later in 1954 by treasure hunters. Ricarte's body was exhumed and his tomb now lies in Manila at the Libingan ng mga Bayani. Furthermore, a landmark was inaugurated by historian Ambeth Ocampo, chairman of the National Historical Institute with a granddaughter of Ricarte in April 2002, at his grave in Hungduan.[12]

Memorials

- In 1972, a monument was erected at Yamashita Park in Yokohama, Japan.[3]

- The birth house of Artemio Ricarte is now the Ricarte National Shrine and Museum in Batac, Ilocos Norte, Philippines.

- For battles and deeds accomplished in Cavite, a marker was placed at Poblacion, General Trias, Cavite for General Artemio Ricarte.

In popular culture

- Portrayed by Vic Vargas in the 1972 film El Vibora, one of Ishmael Bernal's early works.

- Portrayed by Pen Medina in the 1992 film, Bayani.

- Portrayed by Ian de Leon in the 2012 film, El Presidente.

- Portrayed by Justin Candado II in the 2013 GMA TV Series, Katipunan.

- Portrayed by Jack Love Falcis in the 2014 film, Bonifacio: Ang Unang Pangulo.

Notes

References

- ↑ "Brief History" Archived 2013-03-14 at the Wayback Machine. Official Website Armed Forces of the Philippines. Retrieved on 2013-04-19.

- ↑ Alvarez 1992, p. 8.

- 1 2 3 'Ri-ka-ru-ru'te', Ambeth Ocampo, Philippine Daily Inquirer

- ↑ Alvarez 1992, p. 47.

- 1 2 "141st birth anniversary of General Artemio 'Vibora' Ricarte". Manila Bulletin. October 20, 2007.

- ↑ Agoncillo 1990, pp. 177–178.

- 1 2 Foreman, J., 1906, The Philippine Islands, A Political, Geographical, Ethnographical, Social and Commercial History of the Philippine Archipelago, New York: Charles Scribner's Sons

- ↑ "G.R. No. L-2189: THE UNITED STATES, plaintiff-appellee, vs. FRANCISCO BAUTISTA, ET AL., defendants-appellants". The Lawphil Project. November 3, 1906.

- ↑ Luna, Maria Pilar S. (1971). "GENERAL ARTEMIO RICARTE y GARCIA: FILIPINO NATIONALIST" (PDF). Asian Studies. University of the Philippines Diliman. 9 (2): 229–241.

- ↑ Bell, Ronald Kenneth (April 1974). The Filipino Junta in Hong Kong, 1898-1903: history of a revolutionary organization (Thesis). Naval Postgraduate School.

- ↑ Ogawa, T., 1972, Terraced Hell, Tokyo: Charles E. Tuttle Company, Inc., ISBN 080481001X

- ↑ "Where is Artemio Ricarte actually buried?". Philippine Daily Inquirer. November 10, 2017. Retrieved July 1, 2023.

9. Ricarte, Artemio (Vibora) The Hispano-Philippine Revolution. Yokohama, Japan, 1926. 99.p

Sources

- Agoncillo, Teodoro A. (1990). History of the Filipino people. R.P. Garcia. ISBN 978-971-8711-06-4.

- Alvarez, Santiago V. (1992). The katipunan and the revolution: memoirs of a general : with the original Tagalog text. Ateneo de Manila University Press. ISBN 978-971-550-077-7.

.jpg.webp)