Kingdom of Arzawa 𒅈𒍝𒉿 ar-za-wa | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1700–1300 BC | |||||||||

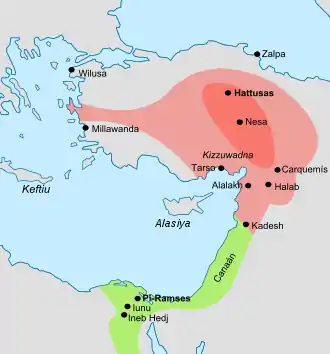

Map of the Arzawa and the surrounding kingdoms, c. 1400 BC. | |||||||||

| Capital | Apaša | ||||||||

| Common languages | Luwian | ||||||||

| Religion | Arzawan religion | ||||||||

| Government | Monarchy | ||||||||

| Kings[lower-alpha 1] | |||||||||

• Late 15th century BC | Kupanta-Kurunta | ||||||||

• Early 14th century BC | Tarḫuntaradu | ||||||||

• 1320s BC | Tarkasnawa | ||||||||

• 1320–1300 BC | Uhha-Ziti | ||||||||

| Historical era | Bronze Age | ||||||||

• Establishment | 1700 BC | ||||||||

• Fall to Hittites | 1300 BC | ||||||||

| |||||||||

Arzawa was a region and a political entity in Western Anatolia during the Late Bronze Age (late 15th century BC-beginning of 12th century BC). This name was used in contemporary Hittite records to refer either to a single "kingdom" or a federation of local powers. The core of Arzawa is believed to be along the Kaystros River (modern Küçük Menderes River), with its capital at Apasa, later known as Ephesus. When the Hittites conquered Arzawa, it was divided into three Hittite provinces: a southern province called Mira along the Maeander River; a northern province called the Seha River Land, along the Gediz River; and an eastern province called Hapalla.[1]

It was contemporary to the Assuwa league, which also included parts of western Anatolia, but was conquered by the Hittites c. 1400 BC.[2] Arzawa was the western neighbour and rival of the Middle and New Hittite Kingdoms. On the other hand, it was in close contact with the Ahhiyawa of the Hittite texts, which corresponds to the Achaeans of Mycenaean Greece.[3] Moreover, Achaeans and Arzawa formed a coalition against the Hittites in various periods.[4]

Name

The name Arzawa and its earlier variant Arzawiya is attested in Hittite inscriptions, firstly appearing during the reign of the Hittite king Ḫattušili I (1650–1620).[5] Place names using the ending -iya like the earlier variant Arzawiya are considered Anatolian names.[6]

Language

The languages spoken in Arzawa during the Bronze Age and early Iron Age cannot be directly determined due to the paucity of indigenous written sources. It was previously believed that the linguistic identity of Arzawa was predominantly Luwian, based, inter alia, on the replacement of the designation Luwiya with Arzawa in a corrupt passage of a New Hittite copy of the Laws.[7] However, it was recently argued that Luwiya and Arzawa were two separate entities, because Luwiya is mentioned in the Hittite Laws as a part of the Hittite Old Kingdom, whereas Arzawa was independent from the Hittites during this period. The geographic identity between Luwiya and Arzawa was rejected or doubted in a variety of recent publications,[8] although the ethnolinguistic implications of this analysis remain to be assessed. One scholar suggested that there was no significant Luwian population in Arzawa, but instead that it was predominantly inhabited by speakers of Proto-Lydian and Proto-Carian.[9] The difference between the two approaches need not be exaggerated since the Carian language belongs to the Luwic branch of the Anatolian languages. Thus, the Luwic presence in Arzawa is universally acknowledged, but whether the elites of Arzawa were Luwian in the narrow sense remains a matter of debate.

The zenith of the kingdom was during the 15th and 14th centuries BC. The Hittites were then weakened, and Arzawa was an ally of Egypt.

Arzawa letters

Alliance with Egypt is recorded in the correspondence between the Arzawan ruler Tarhundaradu and the Pharaoh Amenophis III, which is part of the Amarna letters archive found in Egypt. Two of these letters (Nr. 31 and 32) are known as the Arzawa letters, and they played a substantial role in the decipherment of the Hittite language in which they were written.

Jorgen A. Knudtzon, a Norwegian linguist and historian, played a big role in this decipherment. In 1902, he recognized the Hittite language as Indo-European based on their study.[10] He published further two volumes on Amarna letters in 1907 and 1915.

Max Gander (2014) analysed the clay from which the Amarna Letter EA 32 tablet was made based on the petrographical analyses that had been conducted.[11] Three different analytical methods were used in these analyses.

According to him, the results are rather surprising. What would be expected from them, based on general opinion, is that the clay should have come somewhere from the vicinity of Ephesos, which is widely considered as core territory of the Arzawan state. But instead, they point to northern Ionia, and even into Aeolis. Specifically mentioned are the areas around the cities of Kyme (Aeolis) and/or Larissa.[12] But this location is very close to, or even inside of the conventional location of the Seha River Land.[13]

Accordingly, Gander suggests that Seha should be located further to the south. Thus it could be located south of Ephesus, and closer to the valley of Meander River. Such a location was generally considered in older scholarship.[14]

As to Arzawa, Gander suggests that it could have been located closer to what was later called Lydia.

Timeline based on Hittite records

Kingdom of Arzawa

The Indictment of Maduwatta mentions the local noble Maduwatta who sought a marriage alliance with the Arzawan king Kupanta-Kurunta in 15th century BC. He then allied with a certain Attarsiya, the man of Ahhiyawa; the latter country being widely accepted as Mycenaean Greece or part of it.[15] In general during the period 1400-1190 BC Hittite records mention that the populations of Arzawa and Ahhiyawa were in close contact.[16] Hittite sources also mention Apasa (or Abasa), later known as Ephesus, as the capital of the Kingdom of Arzawa.[1][17]

Hittite records in c. 1320-1315 BC mention that Arzawa led an anti-Hittite alliance together with the region of Millawanta (Miletus) under the king of the Ahhiyawa.[18] [19] As a response to this anti-Hittite initiative, the Hittite king Suppiluliuma I led a campaign against Arzawa and his successor Mursili II finally managed to conquer the region around 1300 BC.[19]

The Arzawan capital fell after a short siege by the Hittites. As a result, the king of Arzawa, Uhha-Ziti and his family, fled to Mycenaean-controlled territory.[20] As a result, most of the local population fled. A large number of the population was deported out of Arzawa, while 6,200 comprised the royal share of deportees to serve the Hittite king.[21]

In the wake of these events, Miletus suffered a setback, and was probably burnt by the Hittite King in reprisal of Mycenaean support to the Arzawan cause. Miletus nevertheless stayed under Mycenaean control.[22]

Hittite records also mention Piyama-Radu a local warlord who was active in Arzawa and fled to Mycenaean controlled territory that time. [23] It is not clear if the Arzawan pockets of resistance were overcome by Hittite forces.[24]

Fragmentation

Arzawa was then split by the Hittites into vassal kingdoms:

- Kingdom of Mira,

- Hapalla (transcriptions vary),

- "Seha River Land", now believed to be the region around present-day Gediz River, although some scholars claim it's around Bakırçay river.

- Wilusa (Troy) that became a Hittite vassal during the reign of Mursili's son, Muwatalli.

Attested western Anatolian late Bronze Age regions and/or political entities which, to date, have not been cited as having been part of a wider Arzawa region are:

- Land of Masa/Masha (associable with Iron Age "Mysia")

- Karkisa/Karkiya (associable with Iron Age "Caria")

- Lukka lands (associable with Iron Age "Lycia")

The above kingdoms usually termed "lands" in Hittite registers could have formed part of the Arzawa complex even earlier before the destruction of the Arzawa kingdom.[25]

In 1998, J. David Hawkins succeeded in reading the Karabel relief inscription, located at the Karabel pass, about 20 km from İzmir. This has provided evidence that the kingdom of Mira was actually south of the 'Seha river land', thus locating the latter along the Gediz River.[26]

In c. 1220 BC Ahhiyawa is mentioned supporting another anti-Hittite rebellion in the former Arzawan lands, in particular in the Seha River land.[27] This rebellion occurred during the reign of Hittite king Tudḫaliya IV.[28] This movement failed and provoked Hittite countermeasures: Ahhiyawa was deleted from a Hittite text listing the contemporary Great Powers and a trade embargo was imposed towards Ahhiyawan traders reaching Assyria.[27]

After the collapse of the Hittite Empire at the 12th century BC, the Neo-Hittite states partially pursued Hittite history in southern Anatolia and Syria, the chain seems to have broken as far as the Arzawa lands in western Anatolia were concerned and these could have pursued their own cultural path until unification came with the emergence of Lydia as a state under the Mermnad dynasty in the 7th century BC.

Kings of Arzawa in the 15th to 13th century BC

- Kupanta-Kurunta c.1440s BC

- Tarhundaradu c.1370s BC

- Tarkasnawa, king of Mira, c.1320s BC

- Uhha-Ziti - last ruler c. 1320-1300 BC

Cultural elements

Based on archaeological evidence the Mycenaean influence in local funerary rituals must have been considerable as indicated by the tholos tomb in Kolophon. In Apasa strong cultural links have been pointed with Mycenean Greece as well with the rest of Anatolia. As such this mixture of local Anatolian and Mycenaean cultural elements might indicate that Arzawa was politically dependent on both the Hittites and the Mycenaeans. Nevertheless some kind of Mycenaean control in Arzawan affairs is however not unlikely as far as the archaeological record is concerned.[29]

See also

Notes

- ↑ ḫandawat(i)

References

- 1 2 J. David Hawkins (1998). 'Tarkasnawa King of Mira: Tarkendemos, Boğazköy Sealings, and Karabel.' Anatolian Studies 48:1–31.

- ↑ Kelder, 2003–2004: p. 65–66.

- 1 2 Kelder, 2003–2004: p. 66.

- 1 2 Kelder, 2003–2004: p. 54.

- ↑ Bryce, Trevor (2009). The Routledge Handbook of the Peoples and Places of Ancient Western Asia: The Near East from the Early Bronze Age to the fall of the Persian Empire. Routledge. p. 74. ISBN 9781134159079.

- ↑ Younger, Kenneth Lawson (2016). A Political History of the Arameans: From Their Origins to the End of Their Polities. Atlanta: SBL Press. ISBN 9781628370843.

- ↑ See Melchert 2003; Hawkins 1998; Singer 2005; Hawkins 2009.

- ↑ Hawkins 2013, p. 5, Gander 2017, p. 263, Matessi 2017, fn. 35.

- ↑ Yakubovich 2010, pp. 107-11

- ↑ Die zwei Arzawa Briefe: Die ältesten Urkunden in Indogermanischer Sprache. Leipzig. 1902.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ↑ Max Gander (2014), An Alternative View on the Location of Arzawa. Hittitology today: Studies on Hittite and Neo-Hittite Anatolia in Honor of Emmanuel Laroche’s 100th Birthday. Alice Mouton, ed. p. 163-190

- ↑ Kerschner, M., “On the Provenance of Aiolian Pottery”, in: Naukratis: Greek Diversity in Egypt. Studies on East Greek Pottery and Exchange in the Eastern Mediterranean (The British Museum Research Publication 162), Villing, A. / Schlotzhauer, U. (éds.). British Museum Company, Londres, 2006, 109-126. p.115

- ↑ Max Gander (2014), An Alternative View on the Location of Arzawa. Hittitology today: Studies on Hittite and Neo-Hittite Anatolia in Honor of Emmanuel Laroche’s 100th Birthday. Alice Mouton, ed. p. 163-190

- ↑ Max Gander (2014), An Alternative View on the Location of Arzawa. Hittitology today: Studies on Hittite and Neo-Hittite Anatolia in Honor of Emmanuel Laroche’s 100th Birthday. Alice Mouton, ed. p. 163-190

- ↑ Beckman, Gary; Bryce, Trevor; Cline, Eric, 2012: 69, 99

- ↑ Kelder, 2003–2004: 66

- ↑ J. David Hawkins (2009). "The Arzawa letters in recent perspective, p.76" (PDF). British Museum.

- ↑ Beckman, Gary M.; Bryce, Trevor R.; Cline, Eric H. (2012). "Writings from the Ancient World: The Ahhiyawa Texts" (PDF). Writings from the Ancient World. Atlanta: Society of Biblical Literature: 193. ISSN 1570-7008.

- 1 2 Bakker, Egbert J., ed. (2010). A Companion to the Ancient Greek Language. Chichester: John Wiley & Sons. pp. 217–218. ISBN 9781444317404.

- ↑ Castleden, 2005, p. 127: "The hostility of the land of Arzawa is known from the tablets. King Unhazitis of Arzawa made war on Hatti in alliance with the Greeks; the Arzawan royal family had to flee to Greece when they were defeated."

- ↑ Strauss, Barry (21 August 2007). The Trojan War: A New History. Simon and Schuster. p. 142. ISBN 978-0-7432-6442-6.

- ↑ Kelder, 2003–2004: 66-67

- ↑ Matthews, Roger; Roemer, Cornelia (16 September 2016). Ancient Perspectives on Egypt. Routledge. p. 77. ISBN 978-1-315-43491-9.

- ↑ Kelder, 2003–2004: 67

- ↑ Trevor Bryce (2005). The Kingdom of the Hittites. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-928132-9.

- ↑ Hawkins, J. D. 2009. The Arzawa letters in recent perspective. British Museum Studies in Ancient Egypt and Sudan 14:73–83

- 1 2 Beckman, Bryce, Cline, 2012, p. 282

- ↑ Kelder, Jorrit M. (2010). The Kingdom of Mycenae: A Great Kingdom in the Late Bronze Age Aegean. Pennsylvania State University Press. p. 33. ISBN 978-1-934309-27-8.

- ↑ Kelder, 2003–2004: p. 69-71.

Sources

- Beckman, Gary; Bryce, Trevor; Cline, Eric (2012). The Ahhiyawa Texts. Brill. ISBN 978-1589832688.

- Beckman, Gary M.; Bryce, Trevor R.; Cline, Eric H. (2012). "Writings from the Ancient World: The Ahhiyawa Texts" (PDF). Writings from the Ancient World. Atlanta: Society of Biblical Literature. ISSN 1570-7008.

- Castleden, Rodney (2005). The Mycenaeans. Routledge. ISBN 978-1-134-22781-5.

- Gander, M. 2017. "The West: Philology". Hittite Landscape and Geography, M. Weeden and L. Z. Ullmann (eds.). Leiden: Brill. pp. 262–280.

- Hawkins, J. D. 1998. ‘Tarkasnawa King of Mira: Tarkendemos, Boğazköy Sealings, and Karabel.’ Anatolian Studies 48:1–31.

- Hawkins, J. D. 2009. The Arzawa letters in recent perspective. British Museum Studies in Ancient Egypt and Sudan 14:73–83.

- Hawkins, J. D. 2013. ‘A New Look at the Luwian Language.’ Kadmos 52/1: 1-18.

- Kelder, Jorrit M. (2004–2005). "Mycenaeans in Western Anatolia". Talanta: Proceedings of the Dutch Archaeological and Historical Society. XXXVI–XXXVII: 49–88. Retrieved 6 November 2013.

- Matessi, A. 2017. "The Making of Hittite Imperial Landscapes: Territoriality and Balance of Power in South-Central Anatolia during the Late Bronze Age". Journal of Ancient Near Eastern History, AoP.

- Melchert, H. Craig (ed) (2003). The Luwians. Leiden: Brill.

- Singer, I. 2005. ‘On Luwians and Hittites.’ Bibliotheca Orientalis 62:430–51. (Review article of Melchert 2003).

- Yakubovich, Ilya. (2010). Sociolinguistics of the Luwian Language. Leiden: Brill.