| Ashur-uballit I | |

|---|---|

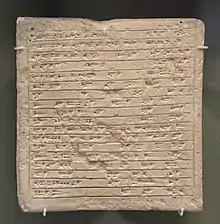

Tablet from the reign of Ashur-uballit I | |

| King of the Middle Assyrian Empire | |

| Reign | c. 1363–1328 BC[1] |

| Predecessor | Eriba-Adad I |

| Successor | Enlil-nirari |

| Issue | |

| Father | Eriba-Adad I |

Ashur-uballit I (Aššur-uballiṭ I), who reigned between c. 1363 and c. 1328 BC, was the first king of the Middle Assyrian Empire. After his father Eriba-Adad I had broken Mitanni influence over Assyria, Ashur-uballit I's defeat of the Mitanni king Shuttarna III marks Assyria's ascendancy over the Hurri-Mitanni Empire, and the beginning of its emergence as a powerful empire. Later on, due to disorder in Babylonia following the death of the Kassite king Burnaburiash II, Ashur-uballit established Kurigalzu II on the Babylonian throne, in the first of what would become a series of Assyrian interventions in Babylonian affairs.

Family and personal life

Burnaburiash married Muballitat-Sherua of Assyria, the daughter of Ashur-uballit I. Together, they had at least one son, Prince Kara-hardash. They may also have been the parents of Kurigalzua II, or his grandparents.

Amarna letters

From the Amarna letters, a series of diplomatic letters from various Middle Eastern monarchs to Amenhotep III and Akhenaten of Egypt, we find two letters from Ashur-uballit I, the second being a follow-up letter to the first. In the letters, Ashur-uballit refers to his second predecessor Ashur-nadin-ahhe II as his "father" or "ancestor," rather than his actual father, Eriba-Adad I, which has led some critics of conventional Egyptian chronology, such as David Rohl, to claim that the Ashur-uballit of the Amarna letters was not the same as Ashur-uballit I. This, however, ignores the fact that monarchs in the Amarna letters frequently refer to predecessors as their "father," even if they were not their biological sons. In this case, Ashur-uballit presumably referred to Ashur-nadin-ahhe because the latter, unlike Eriba-Adad I, had previously corresponded with the Egyptian court.

Babylonian wars

With Assyrian power firmly established, Ashur-uballit started to make contacts with other great nations. His messages to the Egyptians angered his Babylonian neighbour Burnaburiash II, who himself wrote to the Pharaoh: “with regard to my Assyrian vassals, it was not I who sent them to you. Why did they go to your country without proper authority? If you are loyal to me they will not negotiate any business. Send them to me empty-handed!”[2]

Legacy

Prince Kara-hardash succeeded his father. A revolt soon broke out that showed the unpopularity of the Assyrians. Asshur-uballit would not allow his grandson to be cast aside, and duly invaded Babylon. Because Kara-Hardash was killed in the rebellion, the Assyrians placed on the Babylonian throne Kurigalzu II. But this new puppet king did not remain loyal to his master, and soon invaded Assyria. Ashur-uballit stopped the Babylonian army at Sugagu, not far south from the capital Assur.[3]

Ashur-uballit I then counterattacked, and invaded Babylonia, appropriating hitherto Babylonian territory in central Mesopotamia, and forcing a treaty in Assyria's favour upon Kurigalzu.[4]

See also

References

- ↑ Chen, Fei (2020). "Appendix I: A List of Assyrian Kings". Study on the Synchronistic King List from Ashur. Leiden: BRILL. ISBN 978-9004430914.

- ↑ M. van de Mieroop – A history of the ancient near east, 2006, pp. 127–128

- ↑ J. Oates – Babylon, 2003, pp 91–92

- ↑ Georges Roux - Ancient Iraq