The Asian Century is the projected 21st-century dominance of Asian politics and culture, assuming certain demographic and economic trends persist. The concept of Asian Century parallels the characterisation of the 19th century as Britain's Imperial Century, and the 20th century as the American Century.

A 2011 study by the Asian Development Bank found that 3 billion Asians (so 56.6% of the estimated 5.3 billion total inhabitants of Asia by 2050) could enjoy living standards similar to those in Europe today, and the region could account for over half of global output by the middle of this century.[1]

Some argue that Asia's growing emphasis on solidarity, as well as maturing and progressive relationships among countries in the region, will further underpin the creation of the 21st Asian Century.[2][3][4][5][6][7] However, the sharp divide between China and India marks the end of both countries' hopes of leading the Asian Century.[8][9][10]

Origin

In 1924, Karl Haushofer used the term "Pacific age," envisaging the growth of Japan, China and India: "A giant space is expanding before our eyes with forces pouring into it which ... await the dawn of the Pacific age, the successor of the Atlantic age, the over-age Mediterranean and European era."[11] The phrase Asian Century arose in the mid to late 1980s, and is attributed to a 1988 meeting with Paramount leader Deng Xiaoping of China and Prime minister Rajiv Gandhi of India in which Deng said that '[i]n recent years people have been saying that the next century will be the century of Asia and the Pacific, as if that were sure to be the case. I disagree with this view.'[12] Prior to this, it made an appearance in a 1985 US Senate Committee on Foreign Relations hearing.[13] It has been subsequently reaffirmed by Asian political leaders, and is now a popularly used term in the media.

Reasons

Asia's robust economic performance over the three decades preceding 2010, compared to that in the rest of the world, made perhaps the strongest case yet for the possibility of an Asian Century. Although this difference in economic performance had been recognised for some time, specific individual setbacks (e.g., the 1997 Asian financial crisis) tended to hide the broad sweep and general tendency. By the early 21st century, however, a strong case could be made that this stronger Asian performance was not just sustainable but held a force and magnitude that could significantly alter the distribution of power on the planet. Coming in its wake, global leadership in a range of significant areas—international diplomacy, military strength, technology, and soft power—might also, as a consequence, be assumed by one or more of Asia's nation states.

Among many scholars have provided factors that have contributed to the significant Asian development, Kishore Mahbubani provides seven pillars that rendered the Asian countries to excel and provided themselves with the possibility to become compatible with the Western counterparts. The seven pillars include: free-market economics, science and technology, meritocracy, pragmatism, culture of peace, rule of law and education.[14]

Professor John West in his book 'Asian Century … on a Knife-edge'[15] argues:

"Over the course of the twenty-first century, India could well emerge as Asia’s leading power. Already, India’s economy is growing faster than China’s, a trend which could continue, unless China gets serious about economic reform. Further, India’s population will overtake China’s in 2022 and could be some 50% higher by 2100, according to the UN"[16].

In 2019 professor Chris Ogden, a Lecturer in Asian Security at the University of St Andrews, wrote that, "Although still behind relatively in terms of income per capita and infrastructure, as this wealth is translated into military, political, and institutional influence (via bodies such as the United Nations and the new Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank), Asia’s two largest powers will gain a structural centrality and importance that will make them critical global lynchpins. Expectant populations and vocal leaders are accelerating and underpinning this criticality, and—if the existential issues of environmental pollution and corruption can be overcome—herald the emergence of an Asian-centric, and China / India-centric, world order that will form of the essential basis of international affairs for many decades to come."[17]

Demographics

Population growth in Asia is expected to continue through at least the first half of the 21st century, though it has slowed significantly since the late 20th century. At four billion people in the beginning of the 21st century, the Asian population is predicted to grow to more than five billion by 2050.[18] While its percent of the world population is not expected to greatly change, North American and European shares of the global population are expected to decline.[19]

Economics

.png.webp)

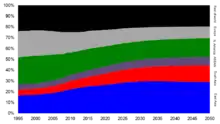

The major driver is continued productivity growth in Asia, particularly in China and India, as living standards rise. Even without completely converging with European or North American living standards, Asia might produce half of the global GDP by 2050. This is a large shift compared to the immediate post-cold war, when North America and Europe combined produced half of the global GDP.[21] A 2011 study by the Asian Development Bank stated that: "By nearly doubling its share of global gross domestic product (GDP) to 52 percent by 2050, Asia would regain the dominant economic position it held some 300 years ago.[24]

The notion of the Asian Century assumes that Asian economies can maintain their momentum for another 40 years, adapt to shifting global economic and technological environment, and continually recreate comparative advantages. In this scenario, according to 2011 modelling by the Asian Development Bank Asia's GDP would increase from $17 trillion in 2010 to $174 trillion in 2050, or half of global GDP. In the same study, the Asian Development Bank estimates that seven economies (China, India, Indonesia, Japan, South Korea, Thailand, Malaysia) would lead Asia's powerhouse growth; under the Asian Century scenario, the region would have no poor countries, compared with eight in 2011.[25]

Since China's economic reforms in the late 1970s (in farm privatisation) and early 1990s (in most cities), the Chinese economy has enjoyed three decades of economic growth rates between 8 and 10%.[26] The Indian economy began a similar albeit slower ascent at the end of the 1980s and early 1990s, and has averaged around 4% during this period, though growing slightly over 8% in 2005, and hitting 9.2% in 2006 before slowing to 6% in 2009,[27] then reaching 8.9% in 2010.[28]

Both of these developments involved policy of a degree of managed liberalisation of the economy as well as a turning outwards of the economy towards globalisation (both exports and attracting inward investment). The magnitude of this liberalisation and globalisation is still subject to debate. They were part of conscious decisions by key political leaders, especially in India and the PRC. Also, the populations of the two countries offer a potential market of over two and a quarter billion.[29] The development of the internal consumer market in these two countries has been a major basis for economic development. This has enabled much higher national growth rates for China and India in comparison to Japan, the EU and even the US.[30] The international cost advantage on goods and services, based on cheaper labour costs, has enabled these two countries to exert a global competitive pressure.[31]

The term Easternization has been used to refer to the spread of oriental (mainly Japanese) management techniques to the West.[32][33][34][35]

The trend for greater Asian economic dominance has also been based on the extrapolations of recent historic economic trends. Goldman Sachs, in its BRIC economic forecast, highlighted the trend towards mainland China becoming the largest and India the second largest economies by the year 2050 in terms of GDP. The report also predicted the type of industry that each nation would dominate, leading some to deem mainland China 'the industrial workshop of the world' and India 'one of the great service societies'.[36] As of 2009, the majority of the countries that are considered newly industrialized are in Asia.

By 2050, the East Asian and South Asian economies will have increased by over 20 times.[37] With that comes a rise in Human Development Index, the index used to measure the standards of living. India's HDI will approach .8. East Asia's would approach .94 or fairly close to the living standards of the western nations such as the EU and the US. This would mean that it would be rather difficult to determine the difference in wealth of the two. Because of East Asian and Indian populations, their economy would be very large, and if current trends continue, India's long-term population could approach double that of China. East Asia could surpass all western nations' combined economies as early as 2030. South Asia could soon follow if the hundreds of millions in poverty continue to be lifted into middle class.

Construction projects

It is projected that the most groundbreaking construction projects will take place in Asia within the approaching years. As a symbol of economic power, supertall skyscrapers have been erected in Asia, and more projects are currently being conceived and begun in Asia than in any other region of the world. Completed projects include: the Petronas Towers of Kuala Lumpur, the Shanghai World Financial Center, International Finance Centre in Hong Kong, Taipei 101 in Taiwan, the Burj Khalifa in Dubai, UAE, and the Shanghai Tower. Future buildings promise to be taller, such as the PNB 118 in Kuala Lumpur and Legacy Tower in Dhaka.

Culture

Culturally, the Asian century is symbolised by Indian genre films (Bollywood, Parallel Cinema), Hong Kong genre films (martial arts films, Hong Kong action cinema), Japanese animation, and the Korean Wave. The awareness of Asian cultures may be a part of a much more culturally aware world, as proposed in the Clash of Civilizations thesis. Equally, the affirmation of Asian cultures affects the identity politics of Asians in Asia and outside in the Asian diasporas.[38]

The Gross National Cool of Japan is soaring; Japanese cultural products, including TV shows, are undoubtedly "in" among American audiences and have been for years.[39] About 2.3 million people studied the language worldwide in 2003: 900,000 South Koreans, 389,000 Chinese, 381,000 Australians, and 140,000 Americans study Japanese in lower and higher educational institutions.

Feng shui books topped the nonfiction best-seller lists and feng shui schools have multiplied. Major banks and multinational corporations employ feng shui consultants to advise them on the organisation of their offices. There has been a readiness to supplement Eastern forms of medicine, therapy, and massage and reject traditional Western medicine in favor of techniques, such as acupressure and acupuncture. Practices such as moxibustion and shiatsu enjoy enormous popularity in the West.[40] So do virtually all the Eastern martial arts, such as kung fu, judo, karate, aikido, taekwondo, kendo, jujitsu, tai chi, qigong, ba gua, and xing yi, with their many associated schools and subforms.[41]

Asian cuisine is quite popular in the West due to Asian immigration and subsequent interest from non-Asians into Asian ingredients and food. Even small towns in Britain, Canada, Scandinavia, or the United States generally have at least one Indian or Chinese restaurant.[42] Restaurants serving pan-Asian and Asian-inspired cuisine have also opened across North America, Australia and other parts of the world. P.F. Chang's China Bistro and Pei Wei Asian Diner which serve Asian and Asian-inspired food is found across the United States and in regards for the former, in other parts of the world as well.[43][44] Asian-inspired food products have also been launched including from noodle brand, Maggi. In Australia, New Zealand, Ireland and the UK an Asian-inspired range of noodles known as Maggi Fusian and a long running range in Germany and Austria known as, Maggi Magic Asia includes a range of noodles inspired by food dishes found in China, Japan, Korea, India, Malaysia, Singapore, Indonesia and Thailand.[45][46]

Yoga has gained popularity outside India and the rest of Asia and has entered mainstream culture in the Western world.[47]

Though the use of English continues to spread, Asian languages are becoming more popular to teach and study outside the continent. The study of Chinese has recently gained greater attention in the United States, owing to a growing belief in the economic advantages of knowing it.[48] It is being encouraged through the PRC's support of Confucius Institutes, which have opened in numerous nations to teach the Chinese language and culture.[49]

Chinese has been rated as the second most used language on the internet with nearly a quarter speaking Chinese, Japanese came as fourth, and Korean as the tenth as of 2010.[50] According to the CIA, China hosted the most users, India the third, Japan the sixth, and Indonesia as the tenth as of 2020.[51]

India has the largest film industry in the world,[52] and Indian Film Industry produces more films than Nollywood and Hollywood.

In the early years of the twentieth century very few people were vegetarians. The figure given for the United Kingdom during World War 2 was 100,000 out of a population of some 50 million – around 0.2 per cent of the total. By the 1990s the figure was estimated as between 4.2 percent and 11 percent of the British population and rising rapidly.[53] As Porritt and Winner observe, as recently as the 1960s and early '70s, "being a vegetarian was considered distinctively odd," but "it is now both respectable and common place."[54][55]

The spread of the Korean wave, particularly K-pop and Korean dramas, outside Asia has led to the establishment of services to sustain this demand. Viki and DramaFever are examples of services providing Korean dramas to international viewers alongside other Asian content.[56][57] SBS PopAsia and Asian Pop Radio are two radio-related music services propagating the proliferation of K-pop throughout Australia. Apart from K-pop, Asian Pop Radio is also devoted to other Asian pop music originating from Indonesia, Thailand, Japan, Malaysia and Singapore.[58] Similarly, SBS PopAsia focuses on other East Asian pop music from China and Japan and to some extent Southeast Asian pop music in conjunction with K-pop. The rising popularity of Asian-related content has resulted in "SBS PopAsia" becoming a brand name for SBS content such as TV shows and news originating from Asia such as China, South Korea, Japan and India.[59]

The growing awareness and popularity of Eastern culture and philosophies in the West has led to Eastern cultural objects being sold in these countries. The most well known being statues of the Buddha which range from statues sold for the garden to items sold for the house. Statues of Hindu gods such as Ganesha and East Asian iconography such as the Yin and yang are also sold in many stores in Western countries. Ishka a chain store in Australia sells many Asian-origin content particularly from India. The selling of Eastern cultural objects has however been met by criticism, with some saying many who buy these items do not understand the significance of them and that it is a form of Orientalism.[60]

Religion

As recently as the 1950s, Crane Brinton, the distinguished historian of ideas, could dismiss "modern groups that appeal to Eastern wisdom" as being in effect "sectarian", "marginal", and "outside the main current of Western thought and feeling".[61] Yet some Westerners have converted to Eastern religions or at least have shown an interest in them. An example is Maharishi Mahesh Yogi, whom the Beatles followed, first to Bangor in Wales in 1967, and subsequently to India to study Transcendental Meditation in 1968. The Dalai Lama, whose book The Art of Happiness became a best-seller, can attract huge crowds in New York's Central Park or London's Wembley Stadium.[62]

Buddhism in some countries is the second biggest religion.[63] FWBO is one of the biggest and fastest-growing Buddhist organisations in the West.[64]

Belief in reincarnation has never been a part of official Christian or Jewish teaching, or at least, in Christianity, it has been a formal heresy since it was rejected by a narrow margin at the Second Council of Constantinople in AD 553.[65] However nearly all polling in Western countries reveals significant levels of this belief. "Puzzled People" undertaken in the 1940s suggested that only 4 per cent of people in Britain believed in reincarnation. Geoffrey Gorer's survey, carried out a few years later, arrived at 5 percent (1955, p. 262). However, this figure had reached 18 percent by 1967 (Gallup, 1993), only to increase further to a sizeable 29 percent by 1979, a good six-fold increase on the earlier "Puzzled People" figure. Eileen Barker has reported that around one-fifth of Europeans now say that they believe in reincarnation.[66]

Karma, which has its roots in ancient India and is a key concept in Hinduism, Buddhism and other Eastern religions, has entered the cultural conscience of many in the Western world. John Lennon's 1970 single, "Instant Karma!" is credited towards the popularisation of karma in the Western world and is now a widely known and popular concept today giving rise to catchphrases and memes and figuring in other forms of Western popular culture.[67][68]

Mindfulness and Buddhist meditation, both very popular in Asia, have gained mainstream popularity in the West.[69]

Politics

The global political position of China and to a lesser extent India has risen in international bodies and amongst the world powers, leading the United States and European Union to become more active in the process of engagement with these two countries. China is also a permanent member of the UN Security Council. Although India is not a permanent member, it is possible that it will become one or at the least gain a more influential position.[70] Japan is also attempting to become a permanent member,[71] though the attempts of both are opposed by other Asian countries (i.e. India's bid is opposed by Pakistan; Japan's bid is opposed by China, South Korea, North Korea).[72]

An Asian regional bloc may be further developed in the 21st century around ASEAN and other bodies on the basis of free trade agreements.[73] However, there is some political concern amongst the national leaderships of different Asian countries about PRC's hegemonic ambitions in the region. Another new organization, the East Asian Summit, could also possibly create an EU-like trade zone.[74]

The Russian Prime Minister Yevgeny Primakov encouraged the idea of a triple alliance between Russia, the PRC and India first formulated by Indian strategist Madhav Das Nalapat in 1983,[75] and supported the idea of a multipolar world.[76]

Human Capital

The 2007 World Bank Report on globalization notes that "rising education levels were also important, boosting Asian growth on average by 0.75 to 2 percentage points."[77] The rapid expansion of human capital through quality education throughout Asia has played a significant role in experiencing "higher life expectancy and economic growth, and even to the quality of institutions and whether societies will make the transition into modern democracies".[78]

3G (Global Growth Generators)

The Asian countries with the most promising growth prospects are: Bangladesh, China, India, Indonesia, Iraq, Mongolia, Philippines, Sri Lanka and Vietnam. Developing Asia is projected to be the fastest growing region until 2050, driven by population and income growth: 9 of 11 3G countries came from Asia.[79] Vietnam has the highest Global Growth Generators Index, China is second with 0.81, followed by India's 0.71.[80]

Based on a report from the HSBC Trade Confidence Index (TCI) and HSBC Trade Forecast, there are 4 countries with significant trade volume growth – Egypt, India, Vietnam and Indonesia – with growth is projected to reach at least 7.3 per cent per year until 2025[81]

Next Eleven

The Next Eleven (known also by the numeronym N-11) are the eleven countries – Bangladesh, Egypt, Indonesia, Iran, Mexico, Nigeria, Pakistan, Philippines, Turkey, South Korea, and Vietnam – identified by Goldman Sachs investment bank and economist Jim O'Neill in a research paper as having a high potential of becoming, along with the BRICs/BRICS, the world's largest economies in the 21st century. The bank chose these states, all with promising outlooks for investment and future growth, on 12 December 2005. At the end of 2011, the four major countries (Mexico, Indonesia, Nigeria and Turkey) also known as MINT, made up 73 percent of all Next Eleven GDP. BRIC GDP was $13.5 trillion, while MIKT GDP at almost 30 percent of that: $3.9 trillion.[82]

Challenges to realising the Asian Century

Asia's growth is not guaranteed. Its leaders will have to manage multiple risks and challenges, particularly:

- Growing inequality within countries, in which wealth and opportunities are confined to the upper echelons. This could undermine social cohesion and stability.

- Many Asian countries will not be able to make the necessary investments in infrastructure, education and government policies that would help them avoid the Middle Income Trap.

- Intense competition for finite natural resources, such as land, water, fuel or food, as newly affluent Asians aspire to higher standards of living.

- Global warming and climate change, which could threaten agricultural production, coastal populations, and numerous major urban areas.

- Geopolitical rivalry between China and India.

- Rampant corruption, which plagues many Asian governments.[83]

- The direct impact of an ageing population on continuous economic development (e.g. declining labour force, change of consumption patterns, strain on public finances[84])

Criticism

Despite forecasts that predict the rising economic and political strength of Asia, the idea of an Asian Century has faced criticism. This has included the possibility that the continuing high rate of growth could lead to revolution, economic slumps, and environmental problems, especially in mainland China.[85]

See also

- Asiacentrism

- Asia Council

- Chindia

- Shanghai Cooperation Organisation

- Regional Comprehensive Economic Partnership

- South Asian Association for Regional Cooperation

- Chinese Century

- Indian Century

- Pax Sinica

- Korean wave

- China's peaceful rise

- Four Asian Tigers

- Tiger Cub Economies

- Cool Japan

- Taiwanese wave

- Post-Western era

References

- ↑ Asia 2050: Realizing the Asian Century | Asian Development Bank. Adb.org. 26 March 2012. Retrieved 28 July 2012.

- ↑ "PM Yıldırım calls Asian countries on cooperation against terrorism". DailySabah.

- ↑ "Regional cooperation and integration benefits Asia and Pacific – Shamshad Akhtar". 23 November 2017.

- ↑ "Momentum for improving Japan-China relations | The Japan Times". The Japan Times.

- ↑ "South Korea, China foreign ministries encourage strong ties". DailySabah.

- ↑ Glaser, Bonnie S. (7 November 2017). "China's Rapprochement With South Korea". Foreign Affairs.

- ↑ "China, Asean to formulate strategic partnership vision towards 2030". The Straits Times. 13 November 2017.

- ↑ Pathak, Sriparna (2 June 2023). "India-China Relations: The End of Hope for an Asian Century". South Asian Voices. Retrieved 8 June 2023.

- ↑ "India's dilemmas in an Asian century". The Hindu. 1 January 2023. ISSN 0971-751X. Retrieved 8 June 2023.

- ↑ March, Louis T. (13 February 2023). "China, India, and the Asian century". MercatorNet. Retrieved 8 June 2023.

- ↑ Cited in Hans Weigert, "Haushofer and the Pacific," Foreign Affairs, 20/4, (1942): p 735.

- ↑ Xiaoping, Deng (1993). Deng Xiaoping Wenxuan (Selected Works of Deng Xiaoping). Vol. 3, Beijing: Renmin chubansh. (People's Publishing House). p. 281.

- ↑ Security and Development Assistance. 1985. Retrieved 28 July 2012.

- ↑ Mahbubani, Kishore (2008). The New Asian Hemisphere: The irresistible shift of global power to the east. Public Affairs. pp. 51–99.

- ↑ "Review: Asia on a knife-edge". lowyinstitute.org. Retrieved 26 August 2019.

- ↑ "The Asian Century Could Belong to India | Asian Century on a Knife-edge". The Kootneeti. 25 April 2018. Retrieved 26 August 2019.

- ↑ Ogden, Chris (19 October 2019). "China and India Set to Dominate the 21st Century". Oxford Reference blog. Oxford University Press. Archived from the original on 20 October 2020.

- ↑ Search Results Archived 30 April 2008 at the Wayback Machine

- ↑ "Human Population: Fundamentals of Growth Population Growth and Distribution". Archived from the original on 20 February 2006.

- ↑ Data table in Maddison A (2007), Contours of the World Economy I-2030AD, Oxford University Press, ISBN 978-0199227204

- 1 2 "Understanding and applying long-term GDP projections – EABER". eaber.org. Archived from the original on 19 May 2019. Retrieved 17 June 2016.

- ↑ "Understanding and applying long-term GDP projections – EABER". eaber.org. Archived from the original on 19 May 2019. Retrieved 18 June 2016.

- ↑ Keillor 2007, p. 83

- ↑ "Asia 2050: Realizing the Asian Century" (PDF). Retrieved 28 July 2012.

- ↑ "Asian 2050: Realizing the Asian Century" (PDF). Retrieved 28 July 2012.

- ↑ "Tag: economic growth rates". China Digital Times. Retrieved 28 July 2012.

- ↑ "Indian Economy Overview". Ibef.org. 20 April 2012. Retrieved 28 July 2012.

- ↑ Goyal, Kartik; Krishnan, Unni (1 December 2010). "Growth May Surpass Government Target for Year, Ushering Higher India Rates". Bloomberg.

- ↑ "Countries Ranked by Population: 1999". 28 December 1998. Archived from the original on 28 November 1999.

- ↑ "Indices & Data | Human Development Reports (HDR) | United Nations Development Programme (UNDP)". Hdr.undp.org. 2 November 2011. Retrieved 28 July 2012.

- ↑ "Asian news and current affairs". Asia Times. 6 August 2009. Archived from the original on 6 August 2009. Retrieved 28 July 2012.

- ↑ Raffin, Anne, "Easternization Meets Westernization: Patriotic Youth Organizations in French Indochina during World War 2"

- ↑ Kaplinsky, Raphael, Easternization: The spread of Japanese Management Techniques to Developing Countries

- ↑ Kwang-Kuo Hwang, Easternization: Socio-cultural Impact on Productivity

- ↑ Campbell, Colin (2015). Easternization of the West. Routledge. p. 376. ISBN 9781317260912.

- ↑ David, Jacques-Henri. "In 2020, America Will Still Dominate Global Economy", Le Figaro, 25 August 2005. Retrieved 21 September 2006.

- ↑ "Asia's Future in a Globalized World". Cap-lmu.de. Retrieved 28 July 2012.

- ↑ "Culture of Asia – Music, Art and Language". Asianamericanalliance.com. Retrieved 28 July 2012.

- ↑ Leach, Emily. "Cool Japan: Why Japanese remakes are so popular on American TV, and where we're getting it wrong". Asianweek.com. Archived from the original on 15 September 2008. Retrieved 28 July 2012.

- ↑ Colin Campbell, Easternization of the West" p. 19

- ↑ Colin Campbell, Easternization of the West" p. 20

- ↑ Colin Campbell, Easternization of the West" p. 21

- ↑ "Asian Cuisine & Chinese Food Restaurant | P.F. Chang's". pfchangs.com.

- ↑ "Pei Wei Asian Kitchen | Asian Done a Better Way". peiwei.com.

- ↑ "Maggi® Fusian® Noodles Products". Maggi®. Archived from the original on 2 April 2019. Retrieved 18 November 2016.

- ↑ "MAGGI MAGIC ASIA Noodle Cup Chicken". Archived from the original on 18 November 2016. Retrieved 18 November 2016.

- ↑ Cushman, Anne (28 August 2007). "Yoga Today: Is Yoga Becoming Too Mainstream?". Yoga Journal.

- ↑ Paulson, Amanda. "Next hot language to study: Chinese", The Christian Science Monitor, 8 November 2005. Retrieved 21 September 2006.

- ↑ "US to Open First Confucius Institute". China.org.cn. 8 March 2005. Retrieved 28 July 2012.

- ↑ "Top Ten Internet Languages – World Internet Statistics". Internetworldstats.com. Retrieved 28 July 2012.

- ↑ "Country Comparison: Internet Users". CIA – The World Factbook. Cia.gov. Archived from the original on 13 June 2007. Retrieved 15 March 2020.

- ↑ "World rankings: Number of feature films produced and key cinema data, 2008–2017". Screen Australia. 2018. Retrieved 15 March 2020.

- ↑ Cohen, 1999.

- ↑ Porritt, Jonathan; Winner, David (1988). The Coming of the Greens. Fontana/Collins.

- ↑ Colin Campbell, "Easternization of the West" p. 80

- ↑ "Korean Drama, Taiwanese Drama, Bollywood, Anime and Telenovelas free online with subtitles - Rakuten Viki". viki.com.

- ↑ "Thank you for nine great years". dramafever.com.

- ↑ "About: Asia Pop Radio". Archived from the original on 12 November 2016. Retrieved 9 October 2016.

- ↑ Choi, JungBong; Maliangkay, Roald (15 September 2014). K-pop - The International Rise of the Korean Music Industry. Routledge. ISBN 9781317681809 – via Google Books.

- ↑ Blakkarly, Jarni (19 August 2014). "Appreciation or Appropriation? The Fashionable Corruption of Buddhism in the West". ABC Religion & Ethics.

- ↑ Colin Campbell, Easternization of the West" p. 29

- ↑ Colin Campbell, Easternization of the West" p. 23

- ↑ "Buddhism becomes second religion". BBC News. 4 March 2003.

- ↑ Colin Campbell, Easternization of the West" p. 25

- ↑ Weatherhead, Leslie D., The Christian Agnostic

- ↑ Colin Campbell, Easternization of the West" pp. 72–73

- ↑ "How Karma Works". HowStuffWorks. 4 December 2007.

- ↑ "Everything you wanted to know about Karma but were too polite to ask" (PDF). Canadian Broadcasting Corporation. 27 February 2015. Retrieved 27 August 2019.

- ↑ "How the Mindfulness Movement Went Mainstream -- And the Backlash That Came With It". Alternet.org. 29 January 2015.

- ↑ Anbarasan, Ethirajan (22 September 2004). "Analysis: India's Security Council seat bid". BBC News. Retrieved 25 April 2010.

- ↑ Kessler, Glenn (18 March 2005). "U.S. to Back Japan Security Council Bid". The Washington Post. Retrieved 25 April 2010.

- ↑ Reinhard Drifte (2000). Japan's Quest For A Permanent Security Council Seat: A Matter of Pride Or Justice?. Palgrave Macmillan. p. 151. ISBN 978-0-312-22847-7.

- ↑ "ASEAN and India Seal Trade, Cooperation Pacts With Eye on "Asian century"". Asean.org. 15 October 2003. Archived from the original on 4 April 2012. Retrieved 28 July 2012.

- ↑ Buckley, Sarah (14 December 2005). "Asian powers reach for new community". BBC News. Retrieved 25 April 2010.

- ↑ Pocha, Jehangir S. (19 November 2006). "China and US in trophy tug of war". The Telegraph. Calcutta, India. Archived from the original on 19 September 2012.

- ↑ Poulose, T. T. "Russia-China-India: A Strategic Triangle". Asianaffairs.com. Archived from the original on 9 May 2003.

- ↑ "Global Economic Prospects: Managing the next wave of globalization" (PDF). World Bank. Retrieved 8 April 2013.

- ↑ Lutz, Wolfgang; Kc, Samir (3 April 2013). "The Asian Century Will Be Built on Human Capital". East Asia Forum. Retrieved 8 April 2013.

- ↑ "Philippine potential cited". Archived from the original on 24 April 2011. Retrieved 1 March 2011.

- ↑ "Citigroup: Vietnam holds world's highest potential – 3G concept". Archived from the original on 9 March 2011. Retrieved 22 July 2013.

- ↑ "Indonesia fourth in world's trade volume growth". 20 October 2011.

- ↑ "Indonesia negara jagoan masa depan". Retrieved 9 August 2012.

- ↑ "ASIA 2050 – Realizing the Asian Century – Executive Summary" (PDF). Retrieved 28 July 2012.

- ↑ "Impact of Population Aging on Asia's Future Growth" (PDF). Asian Development Bank. Retrieved 8 April 2013.

- ↑ "Coming out". The Economist. 23 March 2006.

Sources

- Keillor, Bruce David (2007). Marketing in the 21st century. Westport, Conn.: Praeger. ISBN 978-0-275-99276-7.

Further reading

- Mahbubani, Kishore (2009) The New Asian Hemisphere: The Irresistible Shift of Global Power to the East. PublicAffairs. ISBN 9781586486716.

External links

- The End of Pax Americana: How Western Decline Became Inevitable by The Atlantic

- The Decline of the West: Why America Must Prepare for the End of Dominance by The Atlantic

- Economic power shift from West to East is poised to gather pace by The Independent

- Global economic balance shifting east by The Globe and Mail

- Report The Global Power Shift to Asia: Geostrategic and Geopolitical Implications by Al Jazeera

- "Security and Development Assistance" authored in 1985 by US Senate Committee on Foreign Relations, published by US GPO

- Population Reference Bureau

- "Next hot language to study: Chinese" by Amanda Paulson. CS Monitor, 8 November 2005.

- "US to Open First Confucius Institute" by chinanews.com, 8 March 2005.

- "Analysis: India's Security Council seat bid" by Ethirajan Anbarasan. BBC News 22 September 2004.

- "U.S. to Back Japan Security Council Bid" by Glenn Kessler. Washington Post 18 March 2005.

- "ASEAN and India Seal Trade, Cooperation Pacts With Eye on "Asian Century"" AFP 30 Nov..

- "Asian powers reach for new community" by Sarah Buckley. BBC News. 14 December 2005.

- "Russia-China-India: A Strategic Triangle" by T T Poulose. Asian Affairs.

- "Asian Century Institute"

Others

Speeches and Political Statements

- "Strong China-India relations to usher in true Asian century: Premier Wen" Comment by PRC Premier Wen Jiabao

- "President Addresses Asia Society, Discusses India and Pakistan" US President George Bush calls 21st century not Asian Century, but Freedom's Century

- "India's power is infinite" PRC Commerce Minister Bo Xilai the future growth and cooperation of India and mainland China, 2006

Forecasts

- NIC 2020 Mapping the Global Future

- BRIC Thesis-pdf

- "Welcome To The Asian Century..." by Jeffrey Sachs

Criticism

- "China, India Superpower? Not so Fast!"

- "Asian Century" an editorial contrasting the American Century versus the Asian Century.

- "An all-new flavour? Australia’s Asian Century" Archived 24 June 2021 at the Wayback Machine an article on cultural aspects of the Asian Century on Erenlai.