| Atahualpa | |

|---|---|

Portrait of Atahualpa by an unknown artist from the Cusco School. Currently located in the Ethnological Museum of Berlin, Germany. | |

| Sapa Inca of the Inca Empire | |

| Reign | 1532–1533 |

| Self-installation | April 1532 |

| Predecessor | Huáscar |

| Successor | Túpac Huallpa (as puppet Sapa Inca of the Inca Empire) |

| Born | c. 1502 Cusco, Quito or Caranqui |

| Died | July 1533 [1] Cajamarca, Inca Empire, modern-day Peru |

| Burial | 29 August 1533 Cajamarca, Tawantinsuyu |

| Consort | Coya Asarpay (queen), Cuxirimay Ocllo (secondary wife) |

| Quechua | Atawallpa |

| Dynasty | Hanan Qusqu |

| Father | Huayna Cápac – Inca Emperor |

| Mother | Discussed: Tocto Ocllo Coca Paccha Duchicela Túpac Palla |

Atahualpa (/ˌætəˈwɑːlpə/), also Atawallpa (Quechua), Atabalica,[2][3] Atahuallpa, Atabalipa (c. 1502 – July 1533),[4] was the last effective Incan emperor before his capture and execution during the Spanish conquest.

Atahualpa was the son of the emperor Huayna Cápac, who died around 1525 along with his successor, Ninan Cuyochi, in a smallpox epidemic. Atahualpa initially accepted his half-brother Huáscar as the new emperor, who in turn appointed him as governor of Quito in the north of the empire. The uneasy peace between them deteriorated over the next few years. From 1529 to 1532, they contested the succession in the Inca Civil War, in which Atahualpa's forces defeated and captured Huáscar.[5]

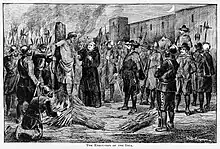

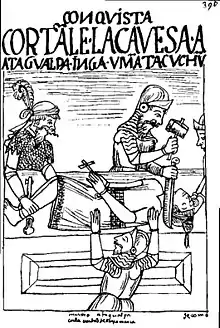

Around the same time as Atahualpa's victory, a group of Spanish conquistadors, led by Francisco Pizarro, arrived in the region. In November, they captured Atahualpa during an ambush at Cajamarca. In captivity, Atahualpa gave a ransom in exchange for a promise of release and arranged for the execution of Huáscar. After receiving the ransom, the Spanish accused Atahualpa of treason, conspiracy against the Spanish Crown, and the murder of Huáscar. They put him on trial and sentenced him to death by burning at the stake. However, after his baptism in July 1533, he was garroted instead.[6]

A line of successors continued to claim the title of emperor, either as Spanish vassals or as rebel leaders, but none were able to hold comparable power.[7][8]

Origin

Name

The name Atahualpa comes from a construction of the Puquina language, a language that was used by the Inca nobility. It is made up of the Quechua words /ata-w/ (appointed or chosen) and /wallpa/ (diligent, diligent or courageous). The word /wallpa/ also originated the Quechua name for the hen and the rooster (guallpa), animals that were introduced to America by the Spanish. The word /wallpa/ originated as an onomatopoeic imitation of the Inca's name while he was imprisoned in Cajamarca. It is based on the account of several chroniclers who declared that every night the roosters began to crow and the followers of the imprisoned Inca assumed that he manifested himself through the bird, portending bad times.

For centuries it was believed that the name Atahualpa came from the Quechua words Ataguallpa, Atabalipa or Atawallpa, whose meanings were erroneously constructed by chroniclers of the time based on the Quechua translation of the word "rooster" or "hen". You have for example: "happy rooster" or "bird of fortune".

Birth

There are uncertainties about Atahualpa's date and place of birth. He was likely born around the turn of the 16th century, c. 1502.[4] There is disagreement on his place of birth. Below are the versions of some chroniclers and historians:

The chronicler and soldier Pedro Cieza de León, from his investigations among the members of the Inca nobility of Cusco, affirmed that Atahualpa had been born in Cusco and that his mother was Tuto Palla or Túpac Palla (Quechua names), a "India Quilaco". » or «native to Quilaco». This demonym could allude to an ethnic group from the province of Quito and would imply that it was a second-class wife, belonging to the regional elite. Cieza de León denied that Atahualpa was born in Quito or Caranqui and that his mother was the lady of Quito, as some at the time claimed, since Quito was a province of Tahuantinsuyo when Atahualpa was born. Therefore, their kings and lords were the Incas.

According to Juan de Betanzos, Atahualpa was born in Cusco and his mother was a ñusta (Inca princess) from Cusco of the lineage of Inga Yupangue (Pachacuti).

In the 18th century, the priest Juan de Velasco, using as a source a work by Marcos de Niza whose existence has not been confirmed, compiled information about the Kingdom of Quito (whose existence has not been confirmed either). According to de Velasco, the Kingdom of Quito was made up of the Shyris or Scyris ethnic group and disappeared when it was conquered by the Incas. This work includes a list of the kings of Quito, the last of whom, Cacha Duchicela, would have been the Kuraka (Inca cacique) defeated and killed by the Inca Huayna Cápac. Paccha, the daughter of Cacha Duchicela, would have married Huayna Cápac, and from that union Atahualpa would have been born as a legitimate son. Several historians, such as the Peruvian Raúl Porras Barrenechea and the Ecuadorian Jacinto Jijón y Caamaño, have rejected this version for lack of historical and archaeological foundation.

Most Peruvian historians maintain that, according to the most reliable chronicles (Cieza, Sarmiento, and Betanzos; who took their reports firsthand), Atahualpa was born in Cusco and his mother was a princess of Inca lineage. These historians consider that Huáscar's side invented the version of Atahualpa's Quito origin to show him to the Spanish as a usurper and bastard. They also believe that many chroniclers interpreted the division of the empire between the two sons of Huayna Cápac (Huáscar, the eldest son and legitimate heir; and Atahualpa, the bastard and usurper) according to their European or Western conception of political mores. According to Rostworowski, this is wrong because the right to the Inca throne did not depend exclusively on primogeniture or paternal line (the son of the Inca's sister could also be heir), but also practical considerations such as the ability to command.

Ecuadorian historians have conflicting opinions:

- According to Hugo Burgos Guevara, the fact that Túpac Yupanqui was born in Vilcashuamán and his son Huayna Cápac in Tomebamba seems to indicate that Atahualpa was born in Quito as part of an expansionist policy of the empire and as a way to reinforce a political-religious conquest.

- Other Ecuadorian historians, such as Enrique Ayala Mora, consider it more likely that Atahualpa was born in Caranqui, in the current province of Imbabura, in the Ibarra canton (Ecuador). They base this idea on the chronicles of Fernando de Montesinos and Pedro Cieza de León (although the latter mentions said version to refute it, in favor of the one from Cusco).

- Tamara Estupiñan Viteri, a historian who has published numerous works regarding Atahualpa and his close circle at that time, maintains that he was born in Cusco.

The following table summarizes the versions of various chroniclers and historians:

| Chronicler or historian | Origin of Atahualpa | Summary of his version | Reliability data |

|---|---|---|---|

| Juan de Betanzos (1510–1576) | Cusco | Atahualpa was born in Cusco while his father was on campaign in Contisuyo. His mother was the ñusta Palla Coca. | |

| Pedro Cieza de León (1520–1554) | Cusco | Atahualpa and Huáscar were born in Cusco. According to the most widespread version heard, his mother was a Quilaco Indian. | |

| Francisco López de Gómara (1511–1559) | Quito | Atahualpa's mother was from Quito. | |

| Pedro Sarmiento de Gamboa (1530–1592)[11] | Cusco | Atahualpa's mother was Tocto Coca, of the Hatun Ayllu lineage. | |

| Inca Garcilaso de la Vega (1539–1616) | Quito | Atahualpa's mother was the crown princess of the Kingdom of Quito, and Atahualpa was born there. | |

| Felipe Guamán Poma de Ayala (1535–1616)[12] | ? | Atahualpa was a bastard Auqui (prince) and his mother was of the Chachapoya culture ethnic group (northern present-day Peru). | |

| Juan de Santa Cruz Pachacuti (16th–17th century) | Cusco | Atahualpa's mother was ñusta Tocto Ocllo Coca. Atahualpa was born in Cusco before Huayna Cápac traveled north. | |

| Bernabé Cobo (1582–1657) | Cusco | Atahualpa was born in Cusco and his mother was the ñusta Tocto Coca. | |

| Agustín de Zárate (1514–1585)[13] | ? | Atahualpa's mother was from Quito. It does not imply that Atahualpa was conclusively born in Quito. | |

| Miguel Cabello de Balboa (1535–1608)[14] | Cusco | When Huayna Cápac made his last trip from Cusco to Quito, he took Atahualpa with him, because his mother had died. This would imply that Atahualpa was born in Cusco. | |

| Juan de Velasco (1727–1792) | Quito | Atahualpa's mother was a Shyri princess of the Kingdom of Quito named Paccha and was one of the four legitimate wives of Huayna Cápac. |

Childhood and youth

Atahualpa spent his childhood with his father in Cusco. At the beginning of his adolescence he went through the Warachikuy, a rite of passage that marked the passage to adulthood.

When Atahualpa was thirteen years old, there was a rebellion in the north of the empire by two peoples from that region, the Caranquis and the Cayambis. Together with his father and his brother, Ninan Cuyuchi marched at the head of the Inca army towards the northern provinces (Quito region). Four governors remained in Cusco, including Huáscar. Atahualpa stayed in Quito with his father for more than ten years, helping him put down rebellions and conquer new lands. For this he had the support of skilled Inca generals, such as Chalcuchímac and Quizquiz. During this period he learned government tasks and gained prestige for the courage he displayed in war actions.

The chroniclers described Atahualpa as someone of "lively reasoning and with great authority".

Pre-conquest

Throughout the Inca Empire's history, each Sapa Inca worked to expand the territory of the empire. When Pachacuti, the 9th Sapa Inca ruled, he expanded the Empire to northern Peru.[15] At this point, Pachacuti sent his son Tupac Inca Yupanqui to invade and conquer the territory of present-day Ecuador.[16] News of the expansion of the Inca reached the different tribes and nations of Ecuador. As a defense against the Inca, the Andean chiefdoms formed alliances with each other.

Around 1460, Tupac Inca Yupanqui, with an army of 200,000 warriors that were sent by his father, easily gained control of the Palta nation in southern Ecuador and northern Peru in a matter of months.[16] However, the Inca army met fierce resistance from the defending Cañari, which left the Incas so impressed that after they were defeated the Cañari were recruited into the Inca army. In northern Ecuador the Inca army met fiercer resistance from an alliance between the Quitus and the Cañari. After defeating them in the battle of Atuntaqui, Tupac Yupanqui sent settlers to what is now the city of Quito and left as governor Chalco Mayta, belonging to the Inca nobility.[17]

Around 1520, the tribes of Quitu, Caras and Puruhá rebelled against the Inca Huayna Cápac. He personally led his army and defeated the rebels in the battle of Laguna de Yahuarcocha where there was such a massacre that the lake turned to blood. According to Juan de Velasco, the alliance of the northern tribes collapsed and finally ended when Huayna Cápac married Paccha Duchicela, queen of the Shyris,[18] making them recognize him as monarch, this marriage was the basis of the alliance that guaranteed the Inca power in the area.[19]

After Huayna Capac died in 1527, Atahualpa was appointed governor of Quito by his brother Huáscar.[20]

Inca Civil War

_(page_130_crop).jpg.webp)

Huáscar saw Atahualpa as the greatest threat to his power, but did not dethrone him to respect the wishes of his late father.[21] A tense five-year peace ensued, Huáscar took advantage of that time to get the support of the Cañari, a powerful ethnic group that dominated extensive territories of the north of the empire and maintained grudges against Atahualpa, who had fought them during his father's campaigns. By 1529, the relationship between both brothers was quite deteriorated. According to the chronicler Pedro Pizarro, Huáscar sent an army to the North that ambushed Atahualpa in Tumebamba and defeated him. Atahualpa was captured and imprisoned in a "tambo" (roadside shelters built for the Chasqui) but succeeded in escaping. During his time in captivity, he was cut and lost an ear. From then on, he wore a headpiece that fastened under his chin to hide the injury. But, the chronicler Miguel Cabello de Balboa said that this story of capture was improbable because if Atahualpa had been captured by Huáscar's forces, they would have executed him immediately.[22]

Atahualpa returned to Quito and amassed a great army. He attacked the Cañari of Tumebamba, defeating its defenses and levelling the city and the surrounding lands. He arrived in Tumbes, from which he planned an assault by rafts on the island Puná. During the naval operation, Atahualpa sustained a leg injury and returned to land. Taking advantage of his retreat, the "punaneños" (inhabitants of Puña) attacked Tumbes. They destroyed the city, leaving it in the ruined state recorded by the Spaniards in early 1532.

From Cuzco the Huascarites attacked the armies of general Atoc and defeated Atahualpa in the battle of Chillopampa. The Atahualapite generals responded quickly; they gathered together their scattered troops, counter-attacked and forcefully defeated Atoc in Mulliambato. They captured Atoc and later tortured and killed him.

The Atahualapite forces continued to be victorious, as a result of the strategic abilities of Quizquiz and Chalcuchímac. Atahualpa began a slow advance on Cuzco. While based in Marcahuamachuco, he sent an emissary to consult the oracle of the Huaca (god) Catequil, who prophesied that Atahualpa's advance would end poorly. Furious at the prophecy, Atahualpa went to the sanctuary, killed the priest and ordered the temple to be destroyed.[23] During this period, he first learned that Pizarro and his expedition had arrived in the empire.[24]

Atahualpa's leading generals were Quizquiz, Chalcuchímac and Rumiñawi. In April 1532, Quizquiz and his companions led the armies of Atahualpa to victory in the battles of Mullihambato, Chimborazo and Quipaipán. The Battle of Quipaipán was the final one between the warring brothers. Quizquiz and Chalcuchimac defeated Huáscar's army, captured him, killed his family and seized the capital, Cuzco. Atahualpa had remained behind in the Andean city of Cajamarca,[25] where he encountered the Spanish, led by Pizarro.[26]

Spanish conquest

In January 1531, a Spanish expedition led by Francisco Pizarro, on a mission to conquer the Inca Empire, landed on Puná Island. Pizarro brought with him 169 men and 69 horses.[27] The Spaniards headed south and occupied Tumbes, where they heard about the civil war that Huáscar and Atahualpa were waging against each other.[28] About a year and a half later, in September 1532, after reinforcements arrived from Spain, Pizarro founded the city of San Miguel de Piura and then marched towards the heart of the Inca Empire, with a force of 106 foot-soldiers and 62 horsemen.[29] Atahualpa, in Cajamarca with his army of 80,000 troops, heard that this party of strangers was advancing into the empire and sent an Inca noble to investigate.[30] The noble stayed for two days in the Spanish camp, making an assessment of the Spaniards' weapons and horses. Atahualpa decided that the 168 Spaniards were not a threat to him and his 80,000 troops, so he sent word inviting them to visit Cajamarca and meet him, expecting to capture them.[31] Pizarro and his men thus advanced unopposed through some very difficult terrain. They arrived at Cajamarca on November 15, 1532.[32]

Atahualpa and his army had camped on a hill just outside Cajamarca. He was staying in a building close to the Konoj hot springs, while his soldiers were in tents set up around him.[33] When Pizarro arrived in Cajamarca, the town was mostly empty except for a few hundred acllas. The Spaniards were billeted in certain long buildings on the main square and Pizarro sent an embassy to the Inca, led by Hernando de Soto. The group consisted of 15 horsemen and an interpreter; shortly thereafter de Soto sent 20 more horsemen as reinforcements in case of an Inca attack. These were led by Francisco Pizarro's brother, Hernando Pizarro.[34]

The Spaniards invited Atahualpa to visit Cajamarca to meet Pizarro, which he resolved to do the following day.[35] Meanwhile, Pizarro was preparing an ambush to trap the Inca: while the Spanish cavalry and infantry were occupying three long buildings around the square, some musketeers and four pieces of artillery were located in a stone structure in the middle of the square.[36] The plan was to persuade Atahualpa to submit to the authority of the Spaniards and, if this failed, there were two options: a surprise attack, if success seemed possible or to keep up a friendly stance if the Inca forces appeared too powerful.[37]

The following day, Atahualpa left his camp at midday, preceded by a large number of men in ceremonial attire; as the procession advanced slowly, Pizarro sent his brother Hernando to invite the Inca to enter Cajamarca before nightfall.[38] Atahualpa entered the town late in the afternoon in a litter carried by eighty lords; with him were four other lords in litters and hammocks and 5,000–6,000 men carrying small battle axes, slings and pouches of stones underneath their clothes.[39] "He was very drunk from what he had imbibed in the (thermal) baths before leaving as well as what he had taken during the many stops on the road. In each of them he had drunk well. And even there on his litter he requested drink."[40] The Inca found no Spaniards in the plaza, as they were all inside the buildings. The only man to emerge was the Dominican friar Vincente de Valverde with an interpreter.[41]

Although there are different accounts as to what Valverde said, most agree that he invited the Inca to come inside to talk and dine with Pizarro. Atahualpa instead demanded the return of every thing the Spaniards had taken since they landed.[42] According to eyewitness accounts, Valverde spoke about the Catholic religion but did not deliver the requerimiento, a speech requiring the listener to submit to the authority of the Spanish Crown and accept the Christian faith.[43] At Atahualpa's request, Valverde gave him his breviary but, after a brief examination, the Inca threw it to the ground; Valverde hurried back toward Pizarro, calling on the Spaniards to attack.[44] At that moment, Pizarro gave the signal; the Spanish infantry and cavalry came out of their hiding places and charged the unsuspecting Inca retinue, killing a great number while the rest fled in panic.[45] Pizarro led the charge on Atahualpa, but captured him only after killing all those carrying him and turning over his litter.[46] Not a single Spanish soldier was killed.

Captivity and execution

On 17 November the Spaniards sacked the Inca army camp, in which they found great treasures of gold, silver and emeralds. Noticing their lust for precious metals, Atahualpa offered to fill a large room about 6.7 m (22 ft) long and 5.2 m (17 ft) wide up to a height of 2.4 m (8 ft) once with gold and twice with silver within two months.[47] It is commonly believed that Atahualpa offered this ransom to regain his freedom, but Hemming says that he did so to save his life. None of the early chroniclers mention any commitment by the Spaniards to free Atahualpa once the metals were delivered.[48]

After several months in fear of an imminent attack from general Rumiñawi, the outnumbered Spanish considered Atahualpa to be too much of a liability and decided to execute him. Pizarro staged a mock trial and found Atahualpa guilty of revolting against the Spanish, practicing idolatry and murdering Huáscar, his brother. Atahualpa was sentenced to death by burning at the stake. He was horrified, since the Inca believed that the soul would not be able to go on to the afterlife if the body were burned. Friar Vincente de Valverde, who had earlier offered his breviary to Atahualpa, intervened, telling Atahualpa that, if he agreed to convert to Catholicism, the friar could convince Pizarro to commute the sentence.[49] Atahualpa agreed to be baptized into the Catholic faith. He was given the name Francisco Atahualpa in honor of Francisco Pizarro.

On the morning of his death, Atahualpa was interrogated by his Spanish captors about his birthplace. Atahualpa declared that his birthplace was in what the Incas called the Kingdom of Quito, in a place called Caranqui (today located 2 km southeast of Ibarra, Ecuador). Most chroniclers agree, though other stories suggest various other birthplaces.[50]

In accordance with his request, he was executed by strangling with a garrote on July 26, 1533.[lower-alpha 1] His clothes and some of his skin were burned and his remains were given a Christian burial.[51] Atahualpa was succeeded by his brother Túpac Huallpa and, later, by another brother, Manco Inca.[52]

Legacy

After the death of Pizarro, Inés Yupanqui, Atahualpa's favorite sister, who had been given to Pizarro in marriage by her brother, married a Spanish knight named Ampuero and left for Spain. They took her daughter by Pizarro with them and she was later legitimized by imperial decree. Francisca Pizarro Yupanqui married her uncle Hernando Pizarro in Spain, on October 10, 1537—they had a son, Francisco Pizarro y Pizarro. The Pizarro line survived Hernando's death, although it is extinct in the male line. Among Inés's direct descendants, having Inca royal ancestry, at least three governed Latin American nations during the 19th and early 20th centuries: Dominican President José Desiderio Valverde and Bolivian Presidents Pedro José Domingo de Guerra and Jose Gutierrez Guerra. Pizarro's third son, by a relative of Atahualpa renamed Angelina, who was never legitimized, died shortly after reaching Spain.[53] Another relative, Catalina Capa-Yupanqui, who died in 1580, married a Portuguese nobleman named António Ramos, son of António Colaço. Their daughter was Francisca de Lima who married Álvaro de Abreu de Lima, who was also a Portuguese nobleman.

In Quito, the most important football stadium is named Estadio Atahualpa after Atahualpa.

On the façade of the Royal Palace of Madrid there is a statue of the Inca emperor Atahualpa, along with another of the Aztec emperor Moctezuma II, among the statues of the kings of the ancient kingdoms that formed Spain.

Inkarri

A myth concerning Atahualpa's death and future resurrection became widespread among indigenous groups, with versions of the tale being documented as far as among the Huilliche people of southern Chile.[54] A rare version recorded by Tom Dillehay among the Mapuche of Araucanía tells of Atahualpa killing Pedro de Valdivia.[54]

Remains

The burial site of Atahualpa is unknown, but historian Tamara Estupiñán argues it lies somewhere in modern-day Ecuador.[55] She argues he was buried in Ecuador for safekeeping. The location is named Malqui-Machay, which in Quechua translates to "mummy"[56] and stone walls and trapezoidal underground water canals were found in this location. More serious archaeological excavation needs to be done to confirm Estupiñán's beliefs.

In popular culture

A treasure hunt for Atahualpa's gold forms the basis for the second Biggles book, The Cruise of the Condor. Atahualpa Inca's conflict with Pizarro was dramatized by Peter Shaffer in his play The Royal Hunt of the Sun, which originally was staged by the National Theatre in 1964 at the Chichester Festival, then in London at the Old Vic. The role of Atahualpa was played by Robert Stephens and by David Carradine, who received a Theatre World Award in the 1965 Broadway production.[57][58] Christopher Plummer portrayed Atahualpa in the 1969 movie version of the play.[59] The closing track of Tyrannosaurus Rex's debut album My People Were Fair and Had Sky in Their Hair... But Now They're Content to Wear Stars on Their Brows was entitled "Frowning Atahuallpa (My Inca Love)"

Atahaulpa plays a key role in Laurent Binet's 2019 alternate history novel Civilizations, journeying across the Atlantic and going on to conquer much of Europe.

See also

Notes

- ↑ Some sources indicate Atahualpa was named after St. John the Baptist and killed on 29 August, the feast day of John the Baptist's beheading. Later research has proven this account to be incorrect.[1]

References

Citations

- 1 2 Hemming 1993, p. 557, footnote 78.

- ↑ Andagoya, Pascual de. "Narrative of Pascual de Andagoya". Narrative of the Proceedings of Pedrarias Davila. The Hakluyt Society. Retrieved 21 June 2019 – via Wikisource.

- 1 2 "Atahuallpa | Biography & Facts | Britannica". www.britannica.com. Retrieved 23 November 2022.

- ↑ Rostworowski, María. History of the Inca Realm. Cambridge University Press.

- ↑ Favre, Henri. Les Incas. Presses Universitaires de France.

- ↑ Cieza de León, Pedro. El Señorio de los Incas.

- ↑ Sarmiento de Gamboa, Pedro. Historia de los Incas.

- ↑ Lauren Jacobi, Daniel M. Zolli (2021). Contamination and Purity in Early Modern Art and Architecture (PDF). Amsterdam University Press. p. 36. ISBN 9789462988699.

- ↑ Guamán Poma (1615). Nueva corónica y buen gobierno. p. 392.

{{cite book}}:|website=ignored (help) - ↑ Pedro Sarmiento de Gamboa (1965). Historia de los Incas (Segunda parte de la Historia General llamada Índica) (PDF). Vol. 135. Madrid, Spain: Ediciones Atlas / Biblioteca de Autores Españoles. p. 151 (71).

- ↑ Felipe Guamán Poma de Ayala (1980). Nueva corónica y buen gobierno. Vol. 1 (1980 ed.). Biblioteca Ayacucho. p. 83. ISBN 9788466000567.

- ↑ Agustín de Zárate (1555). "Capítulo XII. Del estado en que estaban las guerras del Perú al tiempo que los españoles llegaron a ella.". Historia del descubrimiento y conquista del Perú. Julio Le Riverend. p. 544.

- ↑ Miguel Cabello Balboa (1951). Miscelánea antártica: una historia del Perú antiguo (Tercera Parte) (PDF). Instituto de Etnología, Facultad de Letras, Universidad Nacional Mayor de San Marcos. p. 364 (114).

- ↑ Rostworowski 2001, p. 80.

- 1 2 Rostworowski 2001, p. 199.

- ↑ Rostworowski 1998.

- ↑ de Velasco, Juan. Historia del Reino de Quito en la America Meridional.

- ↑ Sosa Freire 1996, pp. 39–40.

- ↑ Espinoza Soriano 1997, p. 105.

- ↑ Herrera Cuntti 2004, p. 405.

- ↑ Pease García-Yrigoyen 1972, p. 97.

- ↑ Quilter 2014, p. 280.

- ↑ Bauer 2005, pp. 4–8.

- ↑ Prescott 1892, pp. 312–317.

- ↑ Prescott 1892, p. 364.

- ↑ Hemming1993.

- ↑ Hemming 1993, pp. 28–29.

- ↑ Hemming 1993, p. 29.

- ↑ Hemming 1993, pp. 31–32.

- ↑ Hemming 1993, p. 32.

- ↑ Hemming 1993, pp. 32–33.

- ↑ Hemming 1993, pp. 33, 35.

- ↑ Hemming 1993, pp. 34–35.

- ↑ Hemming 1993, p. 36.

- ↑ Hemming 1993, p. 39.

- ↑ Hemming 1993, pp. 38–39.

- ↑ Hemming 1993, p. 40.

- ↑ Hemming 1993, pp. 40–41.

- ↑ De Betanzos 1996, p. 263.

- ↑ Hemming 1993, p. 41.

- ↑ Hemming 1993, p. 42.

- ↑ Hemming 1993, pp. 42, 534.

- ↑ Hemming 1993, pp. 42, 534–35.

- ↑ Hemming 1993, pp. 42–43.

- ↑ Hemming 1993, p. 43.

- ↑ Hemming 1993, pp. 39–40.

- ↑ Hemming 1993, pp. 49, 536.

- ↑ DK (November 2011). Explorers: Tales of Endurance and Exploration. Dorling Kindersley Limited. ISBN 9781405365703.

- ↑ Guevara 1995.

- ↑ Hemming 1993, p. 79. "Traitor Ruminaui hearing of the Inca's death fled to Quito where the remaining hoard of the Kings ransom gold was kept in trust by Quilliscacha who now on Atahualpa last wishes was now Inca, but was killed by Ruminaui. Ruminaui killed the Royal Inca descendants for his own greed."

- ↑ Prescott 1892, pp. 438, 447, 449.

- ↑ Prescott 1847, p. 111.

- 1 2 Ajens, Andrés (2017). "Conexiones huilliche-altoperuanas en el ciclo de Atahualpa". MERIDIONAL Revista Chilena de Estudios Latinoamericanos (in Spanish) (8): 153–188.

- ↑ "Atahualpa, Last Inca Emperor". Archaeology. 16 July 2013.

- ↑ Caselli, Irene (12 May 2012). "Ecuador searches for Inca emperor's tomb". BBC News. Retrieved 24 July 2018.

- ↑ "Theatre world Awards Recipients". Theatre World Awards. 2021. Retrieved 7 August 2021.

- ↑ The Royal Hunt of the Sun at the Internet Broadway Database

- ↑ The Royal Hunt of the Sun at AllMovie

Bibliography

- Bauer, Ralph (2005). An Inca Account of the Conquest of Peru. Boulder, CO: University Press of Colorado.

- Brundage, Burr Cartwright (1963). Empire of the Inca. Norman, OK: University of Oklahoma Press. ISBN 9780806119243.

- De Betanzos, Juan (1996). Narrative of the Incas. Translated by Hamilton, Roland; Buchanan, Dana. University of Texas Press. ISBN 9780292755598.

- Espinoza Soriano, Waldemar (1997). Los Incas (in Spanish). Lima: Amaru Editores.

- Guevara, Hugo Burgos (1 January 1995). El Guaman, el puma y el amaru: formación estructural del gobierno indígena en Ecuador. Editorial Abya Yala. ISBN 9789978041680.

- Hemming, John (1993). The Conquest of the Incas. London: Macmillan. ISBN 0333106830.

- Herrera Cuntti, Arístides (2004). Divagaciones históricas en la web (in Spanish). Vol. 2. Chincha: AHC Ediciones. ISBN 9789972290824.

- Hewett, Edgar Lee (1968). Ancient Andean Life. Biblo & Tannen Publishers. ISBN 9780819602046. Retrieved 24 July 2018.

- Kauffmann Doig, Federico (1970). Arqueologia Peruana [Peruvian archaeology]. Lima.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - Pease García-Yrigoyen, Franklin (1972). Los Últimos Incas del Cuzco [The Last Incas of Cuzco] (in Spanish). Lima, Perú: Instituto Nacional de Cultura. p. 97.

- Prescott, William H. (1847). History of the Conquest of Peru. Vol. 2. Harper and Brothers.

- Prescott, William H. (1892). History of the Conquest of Peru. Vol. 1. D. McKay.

- Prescott, William H. (13 October 1998). The Discovery and Conquest of Peru. Modern Library. ISBN 9780679603047.

- Quilter, Jeffrey (2014). The Ancient Central Andes. Oxon, UK: Routledge. p. 280.

- Rostworowski, Maria (1998). History of the Inca Realm. Translated by Iceland, Harry B. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 9780521637596.

- Rostworowski, Maria (2001). Pachacutec Inca Yupanqui (in Spanish). Instituto de Estudios Peruanos. ISBN 9972510603.

- MacQuarrie, Kim (2008). The Last Days of The Incas. Piatkus Books. ISBN 9780749929930.

- Sosa Freire, Rex (1996). Miscelánea histórica de Píntag (in Spanish). Cayambe: Editorial Abya Yala. ISBN 9978042016.

- Veatch, Arthur Clifford (1917). Quito to Bogotá. Doran. Retrieved 24 July 2018.

External links

| Library resources about Atahualpa |

- Atahualpa – World History Encyclopedia

- Francisco de Xeres. Narrative of the Conquest of Peru

- . Appletons' Cyclopædia of American Biography. 1900.