The crash site of Flight 670 | |

| Accident | |

|---|---|

| Date | 10 October 2006 |

| Summary | Runway overrun due to hydroplaning |

| Site | Stord Airport, Sørstokken, Norway 59°47′51″N 5°19′57″E / 59.79750°N 5.33250°E |

| Aircraft | |

| Aircraft type | British Aerospace 146-200A |

| Operator | Atlantic Airways |

| IATA flight No. | RC670 |

| ICAO flight No. | FLI670 |

| Call sign | FAROELINE 670 |

| Registration | OY-CRG |

| Flight origin | Stavanger Airport, Sola |

| Stopover | Stord Airport, Sørstokken |

| Destination | Molde Airport, Årø |

| Occupants | 16 |

| Passengers | 12 |

| Crew | 4 |

| Fatalities | 4 |

| Injuries | 12 |

| Survivors | 12 |

Atlantic Airways Flight 670 was a crash following a runway overrun of a British Aerospace 146-200A at 07:32 on 10 October 2006 at Stord Airport, Sørstokken, Norway. The aircraft's spoilers failed to deploy, causing inefficient braking. The Atlantic Airways aircraft fell down the steep cliff at the end of the runway at slow speed and burst into flames, killing four of sixteen people on board.

The flight was chartered by Aker Kværner from Stavanger Airport, Sola via Sørstokken to transport its employees from there and Stord to Molde Airport, Årø. An investigation was carried out by the Accident Investigation Board Norway (AIBN). It was not able to find the underlying cause of the spoiler malfunction. However, it found that, when the captain selected the emergency braking, the anti-lock braking system was disabled. This selection caused the brakes to completely lock, resulting in reverted rubber hydroplaning, a condition in which the tires became extremely hot due to frictional forces, and the water on the damp runway surface evaporated to steam, effectively causing the tires to float on a cushion of steam over the runway surface, greatly reducing braking action. This situation was made worse with a minimal runway end safety area and lack of grooves in the runway surface.[1]

Flight

Flight 670 was a regular, chartered morning return flight for Aker Kværner to transport its employees from Stavanger Airport, Sola and Stord Airport, Sørstokken to Molde Airport, Årø on 10 October 2006. The aircraft had landed at Sola at 23:30 the day before and a 48 flying hour scheduled inspection was carried out during the night and completed at 05:00. The flight departed Sola at 07:15, just after schedule, with twelve passengers and a flight crew of four. The pilot in command, 34-year-old Niklas Djurhuus, was pilot flying (PF), while the first officer, 38-year-old Jakob Evald, was pilot monitoring (PM).[2] The pilots had flown in as passengers on an Atlantic Airways flight to Stavanger the evening before. The commander had carried out twenty-one landings at Sørstokken previously.[3] The weather was reported as wind speed of 3 metres per second (5.8 kn; 11 km/h; 6.7 mph), a few clouds at 750 metres (2,460 ft) altitude, visibility exceeding 10 kilometres (6 mi; 5 nmi) and air pressure (QNH) of 1,021 hectopascals (102.1 kPa; 14.81 psi).[2]

Aircraft

The aircraft was a British Aerospace 146-200 (BAe 146), serial number E2075, registered OY-CRG, first flown in 1987 and originally sold to Pacific Southwest Airlines, in the United States. Six months later it was sold to Atlantic Airways as the first of this type in its fleet. The last inspection was carried out on 25 September 2006, 2 weeks before the accident. At the time of the accident, the aircraft had flown more than 30,000 hours and about 22,000 cycles.[4]

The BAe 146 is a jetliner specifically designed for short runway operations. Equipped with four Avco Lycoming ALF502R-5 geared turbofan engines, the aircraft is designed for flat landings, where the main and nose landing gears hit the runway nearly simultaneously. It has powerful wheel-brakes and airbrakes, with large spoilers to dump lift immediately on touchdown, but lacks thrust reversers.[5]

Airport and airline

Stord Airport, Sørstokken is a municipal, regional airport located on the peninsula of Sørstokken on the island of Stord at an elevation of 49 metres (161 ft). The runway, aligned 14/32 (roughly north-north-west and south-south-east) is 1,460 metres (4,790 ft) long and 30 metres (98 ft) wide. It has thresholds 130 metres (430 ft) on each end and a landing distance available of 1,200 metres (3,900 ft).[6] At both ends of the runway the ground slopes steeply downwards. This was sufficient safety area according to requirements at the time of the airport's construction, but the requirements had been changed by the time of the accident.[7] The runway was presumed to be damp at the time of the accident, although such information was not relayed to the pilots.[8]

Atlantic Airways is the national airline of the Faroe Islands and was at the time owned by the Government of the Faroe Islands. OY-CRG was one of five BAe 146s in Atlantic Airways' fleet at the time of the accident.[9] The airline was flying a long-term charter contract with for Aker Kværner, who was participating in the construction of the gas field Ormen Lange in the vicinity of Molde. The contract involved regular flights between Stavanger Airport, Sola via Stord Airport, Sørstokken to Molde Airport, Årø and return five times each week. The company also flew to Alta Airport from Stavanger and Stord in relation to the construction of Snøhvit. To allow full take-off weight for the latter service, Atlantic Airways applied the Civil Aviation Authority of Norway on 18 February 2005 for permission to use a longer take-off distance at Sørstokken. This was rejected because the airport's limits were already below international minimum recommendations.[10]

Accident

Flight 670 contacted Flesland Approach at 07:23, stating that they would land on runway 15 and that they would carry out a visual approach. Flesland approach cleared the aircraft for a descent to 1,200 metres (3,900 ft) at 07:24. The aircraft left controlled airspace at 07:27, at which time the aerodrome flight information service (AFIS) at Sørstokken had visual sight of the aircraft. The pilots decided to land at runway 32 as it would give a faster approach. The flaps were extended to 33 degrees at 07:31:12, reducing ground speed from 150 to 130 knots (280 to 240 km/h; 170 to 150 mph).[11] The pilots aimed for a ground speed of 112 knots (207 km/h; 129 mph) at touchdown and were guided by the precision approach path indicator. Upon passing the threshold the aircraft had a slightly high speed, at 120 knots (220 km/h; 140 mph). The aircraft touched down at 07:32:14, a few meters past the ideal landing point, in a soft landing.[12]

The first officer called for the arming of the spoilers one second after touchdown, and the commander armed them half a second later. Two seconds later the first officer called "no spoilers" as the spoiler indicator light had not switched on. He then verified the hydraulic pressure and that the switch was set correctly. Meanwhile, the commander had switched the thrust levers from flight idle to ground idle, and six seconds after touchdown activated the wheel brakes. From 12.8 seconds after touchdown various screeching sounds can be heard from the tires.[12] The braking took place nominally until halfway down the runway. From this point the pilots reported that nominal retardation did not occur. The commander attempted to use the brake pedals to apply full braking, without effect. He then moved the brake lever from green to yellow and subsequently emergency brake, disconnecting the anti-lock.[13] Witnesses observed smoke and spray emitted from the landing gear.[14]

By then, the aircraft had insufficient speed to abort the landing. Aware that the aircraft most likely would overrun, the commander opted to not steer it off the left where there was a steep descent, or to the right where there were rocks. As a last resort, the commander attempted to reduce speed by skidding the aircraft by first steering it right, and then abruptly to the left.[13] The aircraft overran the runway at 22.8 seconds after touchdown, at 07:32:37. At the same time, the crash alarm was activated by AFIS.[12] The aircraft slid off the runway at about a forty-five degree angle, roughly north-west.[14]

Rescue

The AFIS controller activated the emergency alarm at 07:32:40. This was confirmed by the rescue crew four seconds later. Five seconds after that, the AFIS controller called the Emergency Medical Communication Center. The police were then notified four minutes later, as was the Joint Rescue Coordination Centre of Southern Norway, who dispatched air ambulance services. The police arrived at the scene at 07:44.[15]

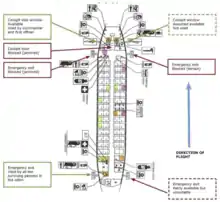

The aircraft landed at a site located 46 metres (151 ft) from the end of the runway and 50 metres (160 ft) from the sea.[16] Once the aircraft had come to a halt, the pilots turned off the fuel supply and activated the engine fire extinguishers. They were not able to order evacuation by intercom, as it was not functioning.[17] The forward starboard door could not be opened due to a jam, while the cockpit and forward port door were both blocked. The pilots evacuated through the left cockpit window, while all surviving passengers evacuated through the aft port door.[15] The pilots attempted to open the jammed front port door, but failed. The commander then re-entered the cockpit to again attempt to open the cockpit door, but failed. By then the heat hindered further attempts. Both pilots were seriously injured in the process. The injured were flown to hospital by air ambulance.[17] Several of the passengers sitting close to the front of the aircraft decided to evacuate towards the aft, as that part of the aircraft was more intact.[18]

After it slid off the runway, parts of the aircraft caught fire. This reached high intensity and centered around the middle section of the fuselage and the right wing.[19] The fire was not started when the aircraft left the runway, but commenced no later than 13 seconds afterwards. Forty-five seconds after the overrun the first fire engine arrived at the scene, the second five seconds after that. By 1 minute and 45 seconds after overrun, most of the fuselage was on fire. The tail collapsed at 3 minutes and 30 seconds after the overrun, and at 5 minutes and 45 seconds after the overrun the inside left engine stopped running. One fire engine left to resupply with water at 8 minutes, returning at 13 minutes. The first municipal fire engine came to the scene after 18 minutes.[20] The fire crew initially did not see anyone near the wreckage and presumed all the passengers had died. Only later did they realize that people standing nearby were actually survivors.[21] The fire was extinguished at 09:30.[22]

Most of the fuselage was destroyed in the fire.[16] Exceptions included the nose and the underside of the cockpit. The tips of the wings and ailerons were nearly undamaged. The front wing spar was sufficiently intact that it was able to keep the wings together. The inner parts of the wing, including the spoilers, were destroyed, but two of the spoiler actuators were salvageable.[23] The tail was largely intact. Most light alloy components in the engines were destroyed, although the compressor blades were intact and showed no sign of damage prior to impact.[24] Three components – the left main landing gear, an engine cowling and the outer right engine – were found between the runway and the wreckage, and had not been consumed in fire.[16]

Investigation

The investigation was carried out by the Accident Investigation Board Norway (AIBN), who arrived by helicopter at the scene at 13:08.[25] Three individuals filmed the accident, of which one was especially useful: from 13 seconds after the aircraft left the runway and subsequent 21 minutes was filmed by a witness across Stokksundet, 1.5 kilometres (1 mi; 1 nmi) from the site of impact. He sold the tape to TV 2, which subsequently handed the video over to AIBN.[19] The investigators concluded that the runway was damp when they arrived, but were not able to conclude if it was wet at the time of the accident.[8] It was nearly impossible to carry out a meaningful investigation of the fuselage because of the heat damage,[23] although the detached left landing gear could be investigated.[19]

The commission mapped all skid marks on the runway. The first skid marks found to be by OY-CRG was at 945 metres (3,100 ft) past the threshold for runway 32.[26] The aircraft also left rubber tire debris.[27] Initially following the centerline, the aircraft was found to drift to the right after 1,140 metres (3,740 ft) and then shifted direction after 1,206 metres (3,957 ft). From 1,274 metres (4,180 ft) the aircraft was skidding to the left, gradually reaching an angle of twenty-five degrees, at the time it ran off the runway at 1,465 meters (4,806 ft).[27]

The flight data recorder was recovered but had sustained substantial fire damage, exceeding its design limits. The tape-based Plessey Avionics PV1584J was sent to the Air Accidents Investigation Branch for investigation. They were only able to extract three segments of the flight, one hour during the flight from the Faroe Islands to Stavanger; 12 seconds during the approach to Sørstokken, ending 43 seconds before the final segment, which lasts for 3 seconds, ending three seconds before the end of the recording.[28] The Fairchild A100S cockpit voice recorder used a solid-state storage medium. It was sent to the same laboratory, but no data could be retrieved there due to fire damage in the circuit board.[26] However, when sent to the manufacturer, they were able to apply repairs to successfully retrieve the content.[25] The sound files were sent to the Accident Investigation Board Finland, who were able to establish a timeline and that the spoiler lever had been set correctly.[29]

All cockpit communication was strictly related to the flight and proper crew resource management was executed.[11] The pilot stated that he believed the aircraft had sufficiently low speed that it would have stopped had the runway been 50 to 100 meters (160 to 330 ft) longer. The first officer estimated the speed at the overrun time at 5 to 10 kilometres per hour (2.7 to 5.4 kn; 3.1 to 6.2 mph) and that the aircraft would have stopped had the runway been 10 to 15 metres (33 to 49 ft) longer.[13]

The six spoiler actuators were sent to the Royal Norwegian Air Force's facility at Kjeller for examination. Radiographic examinations confirmed that they were all in a closed and locked position.[21] A simulation was carried out in a flight simulator to see if, given the conditions, a 146 could land at Sørstokken without operative spoilers.[29] It concluded that this would be possible with a dry runway, but not if it is wet. An extensive investigation of the spoiler system was carried out by Aviation Engineering, who published their findings on 10 May 2011.[9] AIBN quickly started working out from a hypothesis that the spoilers did not deploy and investigated three possible causes: a mechanical failure in the lever, a failure in two thrust lever micro switches, and an open circuit breaker in the lift spoiler system.[30] In the latter case, it would have been necessary for two of four to fail although one could have failed without being detected.[31]

The commission found that the approach and landing were normal with natural variations but that the spoilers were not deployed when the pilot pulled the lever. No conclusion to the cause was found, although the commission believed it must either have been a mechanical fault in the spoiler lever mechanism or a fault in two of the four thrust lever micro switches. The pilots received warning of the failure of deployment and also noticed the lack of sufficient retardation, but failed to connect the two issues, instead focusing on the wheel brakes. The pilots perceived they would not stop in time and activated the emergency braking system. This system bypasses the antilock braking system and can lock the wheels completely. In this incident the wheels locked and the tyres rapidly heated due to friction with the runway surface. Combined with damp conditions on a non-grooved runway, this situation resulted in reverted rubber hydroplaning, a state where the heated rubber created a layer of steam between the tyres and the runway thereby further significantly decreasing the effectiveness of the braking system and adding approximately 60% to the distance required to stop.[31][32] The lack of runway grooving was decisive for the hydroplaning to take place. The aircraft was estimated to be traveling at 15 to 20 knots (28 to 37 km/h; 17 to 23 mph) at the time of the overrun. Had optimum braking taken place, the aircraft would probably have come to a stop on the runway. The massive damage was not caused by the overrun as such, but rather the steep slopes on the side of the runway.[33]

Further, the commission found that the fire was caused by a fuel leak ignited by a short circuit. This spread to the fuel tanks, leading to the scale of the inferno. Supply of ample oxygen was provided by an engine still running. All people on board had a chance of survival, but that rapid and correct evacuation was decisive for actual survival. Although the fire crew were quick to the scene, they were hindered by the terrain, preventing efficient containment of the fire during the crucial evacuation period.[33] The aircraft and crew were found to be fit, airworthy and certified. No training or procedures were available in case spoilers failed to deploy, and that these could have prevented the accident.[34] The airport's physical geography and lack of adequate safety were decisive in the outcome of the accident.[35]

Aftermath

Flight 670 was the seventh fatal accident of the BAE 146 and the ninth hull loss.[36] It is the only write-off or fatal accident of Atlantic Airways.[37] At an international football match on 11 October between France and the Faroes, a minute's silence was held in memory of the dead.[38] On 17 January 2007, the readers of the Faroese newspaper Dimmalætting voted the two flight attendants the Faroese persons of the year (ársins føroyingar).[39] Following the crash at Stord, Atlantic Airways ceased flights to Stord in Fall 2007. The airline's RJ fleet was phased out in August 2014.

In popular culture

The crash is featured in "Edge of Disaster", an episode in Season 15 of Mayday and premiered on 10 February 2016 on the National Geographic Channel.

See also

References

- ↑ Air Crash Investigation 2016 Episode: "Edge of Disaster".

- 1 2 AIBN: 5

- ↑ AIBN: 13

- ↑ AIBN: 16

- ↑ AIBN: 15

- ↑ AIBN: 35

- ↑ AIBN: 36

- 1 2 AIBN: 34

- 1 2 AIBN: 63

- ↑ AIBN: 64

- 1 2 AIBN: 6

- 1 2 3 AIBN: 8

- 1 2 3 AIBN: 9

- 1 2 AIBN: 10

- 1 2 AIBN: 55

- 1 2 3 AIBN: 47

- 1 2 AIBN: 58

- ↑ AIBN: 59

- 1 2 3 AIBN: 52

- ↑ AIBN: 53

- 1 2 AIBN: 61

- ↑ AIBN: 54

- 1 2 AIBN: 48

- ↑ AISN: 49

- 1 2 AIBN: 42

- 1 2 AIBN: 41

- 1 2 AIBN: 46

- ↑ AIBN: 40

- 1 2 AIBN: 62

- ↑ AIBN: 79

- 1 2 AIBN: 99

- ↑ Air Crash Investigation 2016 Episode: "Edge of Disaster".

- 1 2 AISN: 100

- ↑ AIBN: 101

- ↑ AIBN: 102

- ↑ "British Aerospace BAe-146". Aviation Safety Network. Retrieved 25 April 2014.

- ↑ "Atlantic Airways". Aviation Safety Network. Retrieved 25 April 2014.

- ↑ Silence before the match Portal.fo, October 10, 2006

- ↑ Guðrun and Maibritt are Faroese of the Year Archived 2007-09-27 at the Wayback Machine Portal.fo, January 17, 2007