| Attack at the Lower Sioux Agency | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the Dakota War of 1862 | |||||||

The stone warehouse built in 1861, the only original building remaining on the Lower Agency site | |||||||

| |||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

|

| Santee Sioux | ||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

| Chief Little Crow | |||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||

|

20 killed 10 captured 47 escaped | None noted | ||||||

The Attack at the Lower Sioux Agency was the first organized attack led by Dakota leader Little Crow in Minnesota on August 18, 1862, and is considered the initial engagement of the Dakota War of 1862. It resulted in 13 settler deaths, with seven more killed while fleeing the agency for Fort Ridgely.[1]

Tensions had run high in the weeks leading up to the attack. Many eastern Dakota were angered by the refusal of traders to extend credit during a summer of starvation and hardship, and the failure of the United States Indian agents to deliver annuity payments as required by treaty.[1][2] The initial attack on the Lower Sioux Agency by a faction of the eastern Dakota focused on the four trading stores, which they proceeded to raid for flour, pork, clothing, whiskey, guns, and ammunition.[3]

The attack at the Lower Agency was followed by the Battle of Redwood Ferry.[1] Violence soon spread to isolated farms and settlements in Brown and Renville Counties,[1] with an estimated 200 settlers killed and another 200 captured.[4] Some settlers’ lives were saved after they were warned by the Dakota to flee.[3]

Prelude

After the initial conflict at Acton Township, Minnesota on August 17, in which five white settlers were killed by four young Wahpeton Dakota hunters from Rice Creek village, tensions were running high.[1] Similar incidents in the past had resulted in only the perpetrators being punished.[2] However, "traditionalist" leaders such as Cut Nose, the "head soldier" of the soldiers' lodge,[3] and Red Middle Voice, the head of the Rice Creek band,[1] grasped that the situation presented an opportunity to lead an uprising against the Americans, who had withheld annuity payments and provisions during a summer of starvation and hardship for many eastern Dakota.[2] They were also aware that the Americans were in the midst of their own Civil War, and were "getting short of men".[3]

In the middle of the night, Red Middle Voice and his nephew, Chief Shakopee III (also known as Little Six), convened a council at Little Crow's house.[1] Taoyateduta Little Crow was viewed as "the last of the major Mdewakanton chiefs to hold out against acculturation", whose support was essential to convincing others to go to war.[2] Although Little Crow initially hesitated, warning that it was futile to go to war against the Americans, he eventually agreed to lead an uprising, and ordered an attack on the nearby Lower Sioux Agency the following morning.[1]

On the morning of August 18, several traders happened to be away from the Lower Sioux Agency, including Nathan Myrick, Major William H. Forbes, and Captain Louis Robert, leaving others in charge of their stores.[5]

Participants

In the early morning, a group of Dakota soldiers marched toward the Lower Sioux Agency, also known as the Redwood Agency.[3] Dominant within the group were men from the villages of Red Middle Voice and Shakopee.[3] They were joined by others from the villages of Mankato, Big Eagle, and Little Crow.[3] Chief Wabasha III opposed the war and refused to lead a group.[1] Several Dakota men and women went to warn their relatives and friends living in the vicinity.[3]

Many leaders lacked control over their bands, as young braves acted without heeding their warnings.[1] Historian Gary Clayton Anderson argues that the soldiers' lodge or akicita from Shakopee's village asserted authority in leading the attack, given Shakopee's inexperience as a leader, and the age of his elderly uncle, Red Middle Voice.[3] Anderson also suggests that the pattern of killing seemed "selective", with those perceived as having insulted Dakota religion or medicine men, or who had refused to assist the Dakota with food or credit, targeted first.[3] One young soldier, Tawasuota (Much Hail), was one of the first to attack.[3][5]

Attack

On the morning of August 18, a large party of soldiers surrounded the Lower Sioux Agency, a settlement including the quarters of the Indian agent, other government personnel, traders' stores, barns, and other buildings.[1] Separating into small groups, they surrounded the four trade houses at the Lower Agency,[3] firing at once on signal.[1]

The following were killed in the initial attack:

- James W. Lynd, a former state senator who was working as a clerk at Myrick's trading store. Lynd, who had a Dakota wife with whom he had two children, was the first to be killed.[1] Tawasuota ran toward him, screaming, "Now I will kill the dog who would not give me credit."[3][5][lower-alpha 1]

- Andrew Myrick, the "most hated of the traders" for having refused the Dakota credit earlier that summer when they were starving.[1] He was hit by two balls, one in the arm and one in the side.[3] Myrick escaped from the post storehouse through an attic window, but was killed before he could reach cover.[1][3] His corpse was later found with his mouth stuff full of grass.[1][2] Many have interpreted this as retaliation for saying, "Let them eat grass."[1]

- George W. Divoll, another clerk at Myrick's store, and "old Fritz", the cook.[3] Both men were behind the counter when they were gunned down.[3]

- Francois LaBathe, a trader of French and Dakota heritage,[3][6] who was related to Chief Wabasha.[5] LaBathe was killed in his own store.[5]

- Joseph E. Belland and Antoine Young, clerks at William Forbes's store.[5]

- Patrick McClellan, a clerk at Louis Robert's store.[3]

- Alexis Dubuque, a clerk for either Forbes or Myrick.[5]

Three unarmed government workers were killed on the order of Little Crow, when they confronted the Dakota soldiers in an effort to prevent them from stealing horses.[3] These included A. H. Wagner, the superintendent of farms; John Lamb, the hostler; and Lathrop Dickinson.[3][5] Philander Prescott, an elderly fur trader who had lived among the Dakota for forty years and had a Dakota family, was killed while running toward his house.[3][lower-alpha 2]

A total of thirteen victims were killed at the Lower Agency.[1]

Escape and pursuit

Many of the Dakota soldiers proceeded to raid the trading stores for flour, pork, clothing, whiskey, guns, and ammunition.[3] The attack was suspended long enough for as many as fifty to escape to the thickets below the bluff from the Dakota soldiers.[7] From there, the civilians made their way toward Fort Ridgely, which was fourteen miles away.[7] Some were helped across the river by the ferryman, whose name is disputed,[1] before he himself was murdered; others fled by foot.[7] One of the last to cross the river by ferry was Reverend Samuel D. Hinman, who fled by buggy after encountering Little Crow.[3] Seeing Taoyateduta's sullen expression, Hinman had asked, "Crow, what does this mean?" and realized he was in danger when he received only a fierce glare in reply.[3]

Nonetheless, seven more settlers were overtaken and killed while in flight.[1][lower-alpha 3] These included Dr. Philander P. Humphrey, the agency physician, his sick wife, and two of his children.[1][5] Dr. Humphrey and his family were killed after they had crossed the river and gone four miles, stopping to allow his wife to rest when she was unable to continue.[5] Only his twelve-year-old son, who had been sent to get water for his mother, survived and eventually reached the fort.[5]

The life of George Spencer, a clerk at William Forbes's trading store, was spared after his friend Wakinyantawa, a veteran soldier, intervened and declared that Spencer was under his protection and should not be killed.[3] Spencer, who had been wounded during the initial attack, was instead taken captive for the duration of the war,[1] while William Bouratt, who was part-Dakota, was allowed to escape.[3]

Aftermath

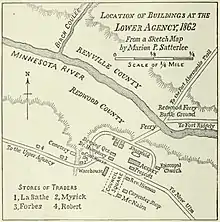

According to historian Marion P. Satterlee, approximately 85 people resided at the Lower Sioux Agency at the time of the attacks.[7] In Massacre at the Redwood Indian Agency, he states that a total of 13 people were killed at the agency; another seven were killed while in flight.[7] About ten were captured and 47 people escaped.[7] Once the buildings of the Lower Agency had been emptied of their contents, they were torched and burned to the ground.[5]

The hired ferryman who stayed at his post and ferried those who were fleeing was among the victims.[1] Although a granite marker on the north side of the river gives his name as "Charlie Martel",[1] various accounts have suggested that the name of the ferryman was Jacob Mauley or Hubert Millier.[3] As the Dakota attackers started crossing the river in pursuit, Olivier Martell, the proprietor of the ferry, had mounted his horse headed for Fort Ridgely.[3]

Further attacks

As refugees from the massacre started to arrive at Fort Ridgely, Captain John S. Marsh left the fort with a relief force of 47 men and headed toward the Lower Sioux Agency.[1] Marsh and his men were ambushed in what has been called the Battle of Redwood Ferry.[7]

The violence escalated as Dakota soldiers attacked isolated homesteads in Brown and Renville counties, killing an estimated 200 settlers and taking another 200 women, children, and part-Dakota civilians hostage.[4] According to Anderson, "The erratic behavior of the akicita soldiers is indicative of the confusion that abounded, as no one seemed to be in charge."[3]

Notes

- ↑ Historian Kenneth Carley notes that one historian theorized that James W. Lynd was killed by his wife's relatives after having deserted his family for another girl. (Carley, p. 12)

- ↑ Historian Gary Clayton Anderson (2019) suggests that Philander Prescott was killed at the Lower Sioux Agency, while historians Kenneth Carley (1976) and William Folwell (1921) suggest that Prescott was killed on the other side of the river, while trying to escape. (Anderson, p. 85; Carley, p. 14; Folwell, p.p. 109–110)

- ↑ See note above.

References

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 Carley, Kenneth (1976). The Dakota War of 1862: Minnesota's Other Civil War (2nd ed.). St. Paul: Minnesota Historical Society. pp. 5–6, 7–14, 21. ISBN 978-0-87351-392-0.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Wingerd, Mary Lethert (2010). North Country: The Making of Minnesota. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press. pp. 301–306. ISBN 978-0-8166-4868-9.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 29 30 Anderson, Gary Clayton (2019). Massacre in Minnesota: The Dakota War of 1862, the Most Violent Ethnic Conflict in American History. Norman: University of Oklahoma Press. pp. 81–85. ISBN 978-0-8061-6434-2.

- 1 2 "A Map of the U.S.–Dakota War: Aug. 18". US–Dakota War of 1862. Minnesota Historical Society. July 3, 2012. Retrieved July 24, 2022.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 Curtiss-Wedge, Franklyn (1916). The History of Redwood County, Minnesota. Vol. I. Chicago: H. C. Cooper Jr. & Co. pp. 135–139.

- ↑ Murphy, Lucy Eldersveld (2014). Great Lakes Creoles: A French-Indian Community on the Northern Borderlands, Prairie Du Chien, 1750–1860. Cambridge University Press. p. 145. ISBN 9781139992978.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 Folwell, William Watts (1921). "V. The Sioux Outbreak, 1862". A History of Minnesota. Minnesota Historical Society. pp. 109–114.