| The Attack on Marstrand | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the Great Northern War | |||||||

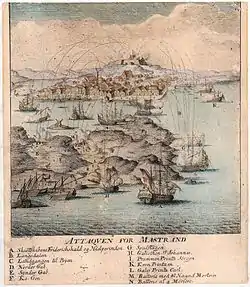

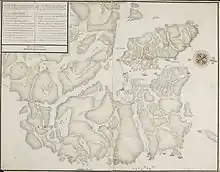

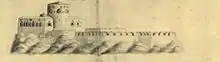

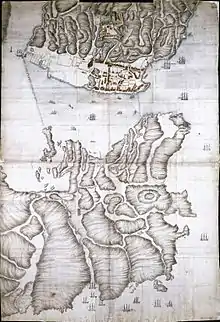

The Swedish Carlsten fortress, Marstrand 1719 | |||||||

| |||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

|

|

| ||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

| Peder Tordenskjold | Henrich Danckwardt | ||||||

| Strength | |||||||

| 600–700 soldiers and sailors. 18 ships including barges, galleys and mortar ships. |

388 total troops 227 soldiers, 54 artillery men, 107 sailors, 6 frigates, 3 galleys, 2 burner ships, 1 barge | ||||||

The Attack on Marstrand was a successful Dano-Norwegian siege of the Swedish town of Marstrand and Carlsten fortress which took place between July 10 and July 16, 1719 during the end of the Great Northern War.

After a Dano-Norwegian assault on northern Bohuslän, ships under the command of Peter Tordenskjold attacked the Swedes at Marstrand harbor and the immobile ships of the Swedish Gothenburg Fleet. The Danes subsequently attacked Carlsten fortress, whose garrison surrendered swiftly, partly because of psychological warfare.

The commander of the fortress, Colonel Henrich Danckwardt, was later sentenced to death by a Swedish court-martial for abandoning the fort while it was still deemed defensible.

The surrender of Carlsten fortress in 1719 is still surrounded by myths and legends.

Background

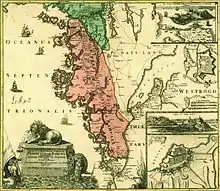

After the death of Charles XII of Sweden on November 30, 1718 at Fredriksten fortress in Norway, the Swedish army marched back across the border to Sweden. The Great Northern War which had been fought continuously since 1700, had depleted fighting forces on both sides. As the Russian Pillage of Sweden posed a threat to Sweden's eastern seaboard, a large part of the Swedish Navy was operating in the Baltic Sea. Denmark-Norway, seeing this as an opportunity, put plans into motion to retake lost territories on the Swedish west coast. There were also plans for a naval and land invasion of Bohuslän.[1]

The Swedish vessels which had previously been stationed in Gothenburg, the Gothenburg Squadron, had been attacked by Peter Tordenskjold's fleet in 1717 and had been ordered by Charles XII to remain scattered along the Bohuslän coast. A majority of the squadron was stationed in Marstrand by the Spring of 1719, and a few smaller ships were located near Strömstad. A couple of smaller vessels escorted transports between Gothenburg and Marstrand on the Nordre River, leaving a single galley to defend Gothenburg. The frigates at Marstrand were not operational, due to a lack of sailors and of food and equipment for the crews. Maintenance of the fortresses was handled poorly and in early 1719, local fortification experts complained over not getting paid for a long time. Similar concerns were raised by the naval officers' corps and the carpenters of Gothenburg.[2]

Blockade and rearmament

At the time, Swedish privateers headquartered in Gothenburg were hijacking foreign vessels. This irritated Dano-Norwegian authorities, so on March 27, a Dano-Norwegian naval force, consisting of four ships of the line and a frigate, anchored in Rivö Bay outside of Gothenburg, blockading the city. The blockading force was under the command of Tordenskjold, who had recently been promoted to the lower admiral rank of schout-bij-nacht.[3] To avoid endangering the peace conference that was to take place in Stockholm in the spring, Tordenskjold was ordered not to assault Gothenburg. In early June, the blockading naval force increased to seven ships of the line, two frigates, four barges, two floating batteries, one bombarderskip, five galleys and two Galliots. The smaller Danish vessels attempted to halt Swedish naval traffic between Nordre river and Marstrand. In mid-June, an additional 26 Danish merchant ships arrived from Øresund with supplies for the Danish blockading fleet.[4]

The stockpiling of supplies in Strömstad in 1718 for Charles XII's army had resulted in the need for emptying the existing supply caches – which were filled to the brim – as quickly as possible. Many Swedish naval transports with cannons and supplies were moved to Sundsborg and Svinesund south towards Uddevalla. The removal of vital supplies caused the defense of northern Bohuslän to falter.[5] By the end of May, a convoy of transport vessels had docked at Marstrand for transshipment to more capable vessels, where the cargo rerouted for further transport through Nordre river. A part of the convoy later returned to Strömstad. On May 23, Field Marshal Carl Gustav Rehnskiöld took command of Swedish troops in Bohuslän. Following an inspection in May, it was deemed that fortifications needed repair in several locations around the region.[6]

The strong Danish blockade outside Gothenburg, with an estimated force of 1,300 soldiers and several special-purpose vessels for bombarding coastal defense positions, implied that the Danes were to attack either Marstrand or Älvsborg fortress. Captain Erik Sjöblad of the Gothenburg Squadron was ordered to moor all frigates and galleys to defend the harbor inlets. Rehnskiöld later gave the order to sink all anchored Swedish ships.[7]

Assault on Strömstad

The peace talks in Stockholm failed, and King Frederick IV of Denmark ordered his troops to attack Sweden. Frederick IV had over 30,000 soldiers available in southern Norway, along with an attack force which would attack Strömstad from the north. A naval force with 8,000 soldiers was to invade Hisingen.[8] The Swedish transport ships in Strömstad could not vacate Strömstad before Danish Vice Admiral Andreas Rosenpalm blockaded the only way out with a naval force of at least three frigates and four galleys at the end of June. After Rehnskiöld and the commander of the Gothenburg Squadron, Admiral Jonas Fredrik Örnfelt, had assessed the situation and had received intelligence that Norwegian forces were indeed marching towards Strömstad, the order was given to scuttle the transport fleet.[9]

Several Swedish galleys and a smaller vessel attempted to slip out of the area at night through an inner channel but this route was blockaded as well. The Gothenburg squadron's galleys Kristiania, Lovisa and Bellona, along with the brig Pollux, were all sunk at Tånge Bay and Tångeflo south of Strömstad on July 5.[10] The Strömstad and Gå På, equipped with 20 cannons each, were also sunk, along with fourteen fully loaded cargo ships in Strömstad harbor.[11] All remaining caches were opened, so that both civilians and military could take what they could, and the remains were then destroyed. Afterwards, Swedish troops under the command of Rehnskiöld totalling around 5,000 – including the garrisons at the fortifications of Gothenburg, Nya Älvsborg and Carlsten – started south towards Uddevalla.[12] The first Danish troops arrived in Strömstad between July 6 and July 8. Frederick IV later arrived along with additional soldiers.[11]

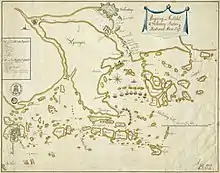

By the end of June, heavy Danish surveillance of the Gothenburg archipelago had been arranged; a force consisting of eight vessels had been deployed between Klåver island and Tjuvkil. Since the vessels were attempting to halt naval traffic between Marstrand and Tjuvkil, and since they were pillaging the archipelago, the Swedes found it highly probable that Tordenskjold was planning to attack Marstrand. The Swedes performed a counter-attack against the Danish blockaders on the night of July 3, when the Swedish galley Lucretia and the brigantines Luren, Uppassaren and Framfuss from Kippholmen in the mouth of Nordre river, managed to creep down Hisingen and get past the Danish reconnaissance fleet without being spotted. The Danish galley Prins Kristian, armed with 9 cannons, was attacked and hijacked at Rivö's mouth.[13]

Battle of Marstrand

Friday, July 10

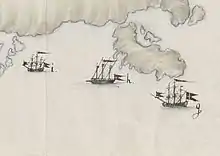

In the first week of July, Tordenskjold scrambled an attack force which he planned to use in his assault on Marstrand. On July 10, the attack began. In the afternoon, the Carlsten fortress garrison reported seeing at least 18 Danish vessels. Tordenskjold had left ships of the line and frigates outside of Gothenburg and the attack force at Marstrand consisted partly of barges armed with cannons and mortars, and galleys with an additional 50 soldiers aboard each ship. Between 600 and 700 soldiers landed at Metsund on the east side of the undefended Koön, east of Marstrand. At the same time, 12 heavy mortars were being transported to the west side of the island. Only the far western part of the island could be bombarded from the fortress. Colonel Henrich Danckwardt, commander of Carlsten had on June 27 requested an additional 400–500 men, to prevent an invasion of Koön and Klåverön (south of Marstrand) but the soldiers had not arrived in time to repel Tordenskjold's attack. The Danish tactic of landing on the east side of Koön was virtually the same as the leading General of Norway, Ulrik Frederik Gyldenløve, had used when he occupied Marstrand and Carlsten at the Battle of Marstrand in July 1677.[14]

Saturday, July 11

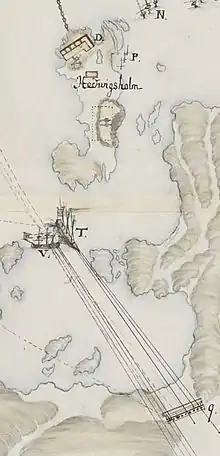

In the morning, heavy barrages were fired from the new Danish artillery stationed at Koön, at Carlsten fortress. Tordenskjold describes in one of his later writings of the new artillery station being heavily fired upon by three Swedish galleys, a barge and three other vessels. He also describes that the Danes were fired upon from Carlsten and its southern outworks. From 6–7 p.m., the cannon fire from Hedvigsholm outwork, which was placed on an island near Koön, consisted of four 36-pounder, two 12-pounder and two 6-pounder cannons. Hedvigsholm was only staffed with twelve men under the command of a non-commissioned officer. When the NCO realized that he would not be able to hold the fortress due to the heavy incoming fire, he sent word to Danckwardt about the situation. Squadron chief Sjöblad decided that the Hedvigsholm battery should be destroyed, to prevent the cannon falling into enemy hands. Danckwardt dispatched Lieutenant Breittenberg to destroy the cannon. Upon his arrival, Breittenberg found that both the Hedvigsholm garrison and the cannon were unharmed, but decided to carry on with his mission. When the Danes noticed that the battery fire from Hedvigsholm had ceased, they started firing upon the Swedish naval vessels in the harbor and managed to sink the vessel which was carrying the crew and ammunition of Hedvigsholm – around seven barrels of gunpowder – to the fortress.[15]

After the events in Marstrand, a military hearing was held at the end of July 1719 with commander Danckwardt. Upon being asked why he had not ordered additional manpower to Hedvigsholm, which was considered the strongest and most effective battery to defend the town, which was also being supported by the galley Prins Fredrik av Hessen, Danckwardt defended his actions by arguing that if he had not destroyed Hedvigsholm, the outwork would have been captured, regardless of its number of personnel. He also pointed out that the enemy would have been able to wade between Koön and Hedvigsholm, something the hearing officials did not agree with.[16]

Sunday, July 12

On Saturday night, another Danish cannon battery had been constructed, even closer to Carlsten and the northern river inlet. It was equipped with four 100-pounder mortars and between thirty and forty lighter mortars. Tordenskjold had also planned on using ten 24-pounder cannon but this was prevented by officers responsible for fortifications and the artillery. These officers had been brought on the ships but were not under Tordenskjolds command. They believed that the battery was unsafe, and refused to hand over the cannon. Fascines and other supplies necessary to produce the battery were not available, according to army officers. Tordenskjold then ordered a fahnenjunkers and nine gunners under his command, together with additional manpower from the ships, to build the battery. The heavy mortars were carried from the northern side of Koön to the new battery. When it was considered ready, Tordenskjold ordered a barrage against Carlsten, which had little effect on the fortress. Even though Tordenskjold had Swedish naval vessels in his firing range, he avoided firing against them in order to attempt to capture them unharmed.[17]

Marstrand falls

From 7–8:00 a.m., the first negotiator was dispatched to Marstrand, Danish Captain-Lieutenant Conrad Ployart who was sailing towards the northern outwork Antonetta – which was guarding the northern inlet – in a sloop with a clearly visible white flag. A Swedish sloop carrying a Lieutenant Brännö was sent to meet with the Danish vessel half-way. Ployart demanded access to the fortress but was told that he should speak with the commander, "His excellency" Field Marshal Rehnskiöld, if he wanted anything.[18] The Danish officer lamented the fact that he could not meet the commander in person and added that if there were any women present in the fortress, they would immediately be given the chance to leave. Ployart had also received orders to offer the Swedes a deal, the Swedes would have to hand over six naval vessels in exchange for the Danes not firing at Marstrand.[19] The Swedes rejected the offer.

After Ployart had returned with the Swedes' rejection, Tordenskjold mounted an assault on the vessels and outworks which were defending the northern harbor inlet. The artillery galiot Johannes and the mortar barge Lange Maren fired the first rounds. Two barges, the Hjælperinden and the Fredrikshald were in reserve. The Swedish outworks consisted of Antonetta – equipped with four 6-pounder cannons and a crew of seven – and the Northern Blockhouse, a smaller outwork equipped with two 36-pounder guns. Captain Sjöblad had stationed an additional three cannons close to the Northern Blockhouse, which were served by 15 men. The outworks did not have enough ammunition and were commanded by NCOs. After firing at the outworks, with the help of a galley and eight sloops, 200–300 Danish soldiers were landed on Marstrand island and close to Antonetta.[19] After the Swedes had returned fire against the landing force, its guns were spiked and the crews retreated to Carlsten. The Northern Blockhouse suffered the same fate and so the Danes, commanded by Captains Kaas and Kleve, could rapidly enter the city. In the harbor, the Swedish frigate Kalmar and the galley Greve Mörner continued to defend the northern inlet until the Danish troops eventually entered the city.[20]

At the war hearing, Danckwardt was asked why he had not contributed more to the defense of the northern inlet outworks. The two outworks could have defended each other by cross fire and he could have sent one of the seven professional officers from Carlsten to act as a commander. Danckwardt defended himself by saying that he could not afford to send away even more personnel from Carlsten and that the men would have been cut off if the outworks were conquered.[21]

Sinking of the Swedish fleet

At the same time as the Danes were storming into the city, Danish sloops were sailing towards the Swedish vessels in the harbor. Since the Swedish ship crews were understaffed, they realized that they would not be able to survive the imminent battle; their only way of retreat towards Carlsten was being blockaded and the Swedish ships fired their last broadsides. Thereafter, the Swedes fired shots at their own vessels' strakes.

Most of the ships' crews managed to return safely to Carlsten. The vessels which were sunk were the frigates Halmstad, Stettin and Kalmar, all armed with 40 cannon, as well as Fredricus (36) and Charlotta (30). The galleys Stå Bra and Greve Mörner with 9 cannons each, the sloop Diana (4) along with two fire ships were sunk. Tordenskjolds soldiers managed to prevent the sinking of the frigates Varberg (40 cannons) and William Galley (14), the galiot Prins Fredrik av Hessen (9) and the barge Ge På (18). William Galley was probably a captured British vessel or possibly a privateer.[22]

During the hearing, Danckwardt mentioned that a few volunteers from the ship crews and the garrison had left the fortress to "overwhelm the enemy" but could not get any further than the castle hill, since enemy soldiers were deployed around Marstrand cemetery, which was close by. The force of volunteers promptly turned back and re-entered the fortress, according to Danckwardt.[23] In the afternoon, firing on Carlsten continued from the mortar batteries on Koön. A shed which was being used as temporary gunpowder storage was hit and exploded. A fire also broke out on the tower roof and on parts of Fyrkantsbatteriet, an outwork on the eastern side of the fortress, which were put out by fortress personnel. No deaths were reported as a result of the artillery fire but Swedish morale was depressed because of the Danish conquering of their outworks and the sinking of the Swedish fleet. On the night to Monday, Tordenskjold landed 200 soldiers on Marstrand island, 500 men in total.[24]

Monday, July 13

During the day, only a few rounds were fired from the fortress and none at all from the Danes. Inside the fortress, the commander ordered artillery officers Captain Josias Mörck and Lieutenant Graan to burn the city down, the officers stated that they did not have any suitable ammunition. At the hearing, Danckwardt was asked why the retreating outwork crews failed to burn the city down, to which he replied that he was not aware that this could have been done any other way except by firing from the fortress. He also argued that the artillery officers unwillingness was because they had their houses inside the city.[25]

The Danes transported the captured vessels away from the area, moving up additional mortars and repairing a cannon battery on Koön, which had sustained fire from the Prins Fredrik av Hessen. Repairs could be done uninterrupted because Carlsten only had one cannon which could reach the battery and this cannon was damaged.[25] The crew of Carlsten consisted of Redväg's company from the Älvsborg Regiment with around 100 men and a company from Zengerlein's Saxon Infantry Regiment which had at least 100 men, both units totalling 227 infantrymen. The artillery, under the command of Captain Mörck, consisted of 54 men. 107 men were acquired from the ship crews as well, the entire crew consisted of a total of 388 men.[26]

The fortress had been heavily expanded since the Danish assault in 1677. This rendered Carlsten one of the most heavily defended fortresses in the country. The fortification of the city of Marstrand and the construction of Carlsten fortress was, and still is, one of the largest investments ever in Swedish static defense.[27]

Tuesday, July 14

Artillery fire against the fortress continued until 11:00 a.m. In the afternoon, Lieutenant Ployart approached the fortress as a negotiator along with an army drummer and asked the Swedes to be let inside. Blindfolded, Ployart was promptly taken to see the Swedish commander. Ployart handed over a sealed letter written by Tordenskjold. The letter, which consisted of flattery and threats, is preserved today in the Danish National Archives.[28] While Danckwardt was preparing a proper reply to the letter, one of his captains brought another letter from Tordenskjold to his attention. In it, Tordenskjold offered a sum of 3,000 ducats and the mercy of the Danish king, if the Swedes surrendered. According to Danckwardt, he had replied to the second letter, that even if he had been offered 300,000 ducats, he would rather have blown the fortress up, than abandoning it for money.[29] Swedish Captain Jacob von Utfall accompanied Ployart to Tordenskjold later in the day and suggested that an armistice would be appropriate, to which Tordenskjold agreed.[30]

When von Utfall had returned to Carlsten, Danckwardt called all officers to a meeting. The protocol of the meeting was later used as an instrument of surrender. The officers explained the situation, the artillery suffered lack of personnel and bad gun carriages. The supply of food was estimated to be able to sustain them for a month but there was a lack of water. The fortress had next to no combat personnel, the naval crews were deemed not of much use in the case of an ambush, due to their lack of combat training, their sole purpose at the fortress was as a fire brigade. Tordenskjold used this time by placing additional light mortars on suitable locations in Marstrand.[31]

Wednesday, July 15

The Swedish meeting continued during the morning. Tordenskjold was still preparing an assault by relocating the Danish barges, floating batteries and galleys closer to the fortress. Since the Carlsten garrison was deemed too exhausted to sustain an assault, the Swedes agreed to surrender before the end of the armistice. All of the Swedish officers signed the instrument of surrender which was handed over to the Danes by Captain von Utfall.[32]

Hwarföre conjunctim resolverades att En formel Capitulation skall giöras genom Capitainen von Uthfall i dhe Puncter och Propositioner som det Jnstrumentet ad acta uthwijsar och aparto underskrifwes. Datum Carlsteen d. 15 Julii 1719

— Quote from the instrument of surrender, Kuylenstierna 1899, pp. 77–78

After two hours, Utfall returned with the document which had been signed by Tordenskjold. All Swedish forces were instructed to leave the fortress by 3:00 p.m., all officers who wished to return to Marstrand were allowed to do so, without being treated as a prisoner of war. The Swedes were granted an additional two hours, properly to vacate the fortress. [33]

At four in the afternoon, Tordenskjold arrived at the fortress gate and was promptly let in. Danckwardt met with him and showed him to the commanders quarters, where the other officers had gathered. After a while of conversation, the commander and a number of officers accompanied Tordenskjold to a house in Marstrand, where they all enjoyed red wine. At 9:00 p.m., all men returned to their quarters. The only breach of the peace was when soldiers from the Saxon regiment and a group of artillerymen broke into a storage facility and stole the butter supply. The Saxon soldiers were ordered to vacate the city and to spend the night standing outside the fortress wall surrounded by armed Danish soldiers.[34]

Thursday, July 16

In the morning, all Swedes marched out of the fortress. At around four in the afternoon, the commander left the fortress for a house in Marstrand. At 9:00 p.m., the remaining Swedish soldiers of the infantry and the artillery vacated the fortress.[35]

Friday, July 17

The Swedish troops were transported to Tjuvkil on the mainland, except for a few troops from the artillery and the Saxon regiment, which were transferred to Danish service. During the transport, Tordenskjold handed out gifts to the officers such as watches and feather fans, along with other goods that had been taken from captured ships. After arriving at Tjuvkil, Danckwardt sent a letter to Field Marshal Rehnskiöld in Uddevalla explaining the situation. After reading the letter, Rehnskiöld issued an arrest warrant for Danckwardt. Danckwardt was arrested at Bohus fortress when he was attempting to travel to Gothenburg.[36]

Aftermath

Field Marshal Rehnskiöld and his officers were now left with a tough decision: should they stay with the Swedish troops at Uddevalla and protect the roads to Vänersborg and Dalsland or move south towards Hisingen, to avoid being cut off by the Danish forces which could land north of Gothenburg? Rehnskiöld chose to stay, which turned out to be a good decision since the Danish army at Strömstad later pulled back into Norway at the end of August.[37] Tordenskjold used the naval base to attack Nya Älvsborg fortress on July 21 and later Nya Varvet at Göta river mouth. While under Dano-Norwegian rule, Carlsten fortress was named Kristiansten and Norwegian Major General Hartvig Huitfeldt was assigned to command the fortress garrison. On November 12, 1720, after the signing of the Treaty of Frederiksborg, the fortress was returned to Swedish control and was once again renamed Carlsten.[38]

On July 22, all officers who had signed the Carlsten instrument of surrender were arrested. After a war hearing with Danckwardt on July 21, a court martial was held on August 27, where he was violently disciplined for his actions.[39] Charles XI's war law § 73 states that any fortress commander that surrenders the fortress to the enemy without being under sufficient distress, shall receive the highest degree of punishment.[40] On September 5, Danckwardt was sentenced to death by beheading in accordance with these laws. The execution took place on September 16. The executioner, Jonas Wessman, was allegedly late and under the influence of alcohol which resulted in him not performing the beheading correctly and was forced to strike three times in order to completely remove the head from the body. Wessman was brought to court, but was let off with a formal warning.[41]

On November 13, 1719, a court martial was held with the arrested Carlsten officers. The officers stated that all documents that they had signed on Carlsten were simply a report on the fortress' defensive capabilities and that the last parts, that documented the official surrendering of the fortress, must have been added after the signing, without their knowledge. Because of this, the officers were not sentenced to death.[40]

Myths

Carlsten's surrender has been compared to Siege of Sveaborg and its surrender in 1808. Psychological warfare was used in both cases to break down their opponents will to fight.[43] Certain events at Marstrand in 1719 have become myths, which can sometimes be confirmed or disproved with the help of documents from the time.

Espionage

Peder Tordenskjold (then known as Peter Wessel) was a crewman on a civilian British vessel in the summer of 1710. Bad weather forced the crew to navigate the vessel towards Marstrand. Peter Wessel seized an opportunity to explore the town's surroundings and fortifications without being suspected as a Danish spy. He left afterwards on a Dutch warship and reported his findings in a letter to Frederick IV, which he sent on February 28, 1711.[44]

Tordenskjold's soldiers

Captain von Utfalls visit to Tordenskjold at Marstrand on July 14, was described in a more detailed way by Danish author Casper Peter Rothe. Rothe claims that Tordenskjold had only between 200 and 300 soldiers present in the city. While the soldiers were being deployed, Utfall was invited into a local tavern. Tordenskjold ordered his men to roam the streets slowly in larger groups so that it would appear to the intoxicated von Utfall that there were at least 1,000 of them.[45] The story is most likely untrue, as the number of Danish soldiers in the city was listed as 500 men on the Swedish instrument of surrender, which corresponds with Danish intelligence.[30]

Reinforcements

In his letter to Danckwardt, Tordenskjold mentions that he was awaiting reinforcements of 2,000 men which were deployed on the Koster Islands. Rothe's version of the same document mentions that the reinforcements consisted of 20,000 men.[46] The threat was not unfounded, General Major Hans Jacob von Arnold was in command of a landing force of around 8,000 men, who were embarked on 28 transport ships near Larkollen but had been forced to return just prior to Tordenskjold's assault due to strong winds. These ships, along with escorts, were supposed to land troops on Hisingen.[47][48]

Defeated and humiliated

Rothe's version of the events at Marstrand, describes Danish soldiers humiliating the captured Swedish officers by verbally abusing them and forcing them to dress up in women's decorative clothing.[42] Other reports suggest the opposite, that Tordenskjold and Danckwardt, along with their officers socialised for several hours on the night of July 15.

Alleged Saxon betrayal

One of Danckwardt's explanations for his actions was that soldiers with the Saxon Infantry Regiment had allegedly mutinied. The regiment, commanded by Colonel Georg David Zengerlein, was composed of Saxon prisoners of war who had been captured during the battles in Saxony-Poland. They had then been conscripted into the Swedish army and were therefore considered badly motivated mercenaries.[49] That these soldiers were merely present at Carlsten, was seen as a weak point by both the Danish and Swedish militaries. Prior to the assault, Field Marshal Rehnskiöld had attempted to dispatch another ship of 150 Swedish soldiers to relieve the 100 Saxon soldiers but owing to a large number of Danish vessels occupying the area, the force had to return to Uddevalla.[50] According to Danish reports, the Danish Captain Kleve had sneaked up to the fortress wall at night and overheard how the Saxon sentries were talking about forcing the commander to surrender.[51] The discipline inside the fortress was poor and women were granted entry into the fortress at night, which was forbidden. Tordenskjold used this to his advantage by smuggling in letters written in German, which urged the Saxon soldiers to surrender.[52] There is nothing relating to a Saxon mutiny stated in the Swedish instrument of surrender. During a war hearing, Captain Palmcrona verified that the Germans were behaving. Colonel Zengerlein of the Saxon Infantry Regiment was the chairman of the war hearing and he would never have been elected to the position if the Swedes had doubted him or his unit.[53]

References

- ↑ Kuylenstierna 1899, pp. 30–31

- ↑ Ericson Wolke 1997, p. 229

- ↑ Försvarsstaben 1949, p. 149.

- ↑ Ericson Wolke 1997, p. 230

- ↑ Modig 2013, p. 127

- ↑ Kuylenstierna 1899, pp. 38–40

- ↑ Försvarsstaben 1949, p. 149–150.

- ↑ Andersen 2004, pp. 284–285

- ↑ Kuylenstierna 1899, p. 53

- ↑ Modig 2013, p. 104

- 1 2 Modig 2013, p. 130

- ↑ Kuylenstierna 1899, p. 48

- ↑ Försvarsstaben 1949, p. 150

- ↑ Kuylenstierna 1899, p. 69

- ↑ Kuylenstierna 1899, pp. 69–70

- ↑ Kuylenstierna 1899, p. 70

- ↑ Kuylenstierna 1899, p. 71

- ↑ Kuylenstierna 1899, p. 72

- 1 2 Andersen 2004, p. 288

- ↑ Kuylenstierna 1899, pp. 72–73

- ↑ Kuylenstierna 1899, p. 73

- ↑ Försvarsstaben 1949, p. 151

- ↑ Kuylenstierna 1899, p. 140

- ↑ Kuylenstierna 1899, pp. 74–75

- 1 2 Kuylenstierna 1899, p. 75

- ↑ Kuylenstierna 1899, p. 65

- ↑ Törnquist, Gezelius & Ericson Wolke 2007, p. 105.

- ↑ Kuylenstierna 1899, p. 152

- ↑ Kuylenstierna 1899, p. 76

- 1 2 Andersen 2004, p. 290

- ↑ Kuylenstierna 1899, pp. 76–77

- ↑ Kuylenstierna 1899, pp. 77–78

- ↑ Kuylenstierna 1899, p. 78

- ↑ Kuylenstierna 1899, pp. 78–79

- ↑ Kuylenstierna 1899, p. 79

- ↑ Kuylenstierna 1899, pp. 79–80

- ↑ Kuylenstierna 1899, pp. 58–59

- ↑ Kuylenstierna 1899, pp. 80–81

- ↑ Kuylenstierna 1899, p. 80

- 1 2 Kuylenstierna 1899, p. 84

- ↑ Feiff 1998, pp. 47–51

- 1 2 Rothe 1773, p. 173

- ↑ Ericson Wolke 1997, p. 232

- ↑ Andersen 2004, p. 46.

- ↑ Rothe 1773, p. 164.

- ↑ Rothe 1773, p. 162.

- ↑ Andersen 2004, p. 285.

- ↑ Kuylenstierna 1899, p. 46.

- ↑ Ericson Wolke 1997, p. 197.

- ↑ Kuylenstierna 1899, p. 82–83.

- ↑ Kuylenstierna 1899, p. 82.

- ↑ Kuylenstierna 1899, p. 153.

- ↑ Kuylenstierna 1899, p. 81.

Sources

- Andersen, Dan H. (2004). Mandsmod og kongegunst: en biografi om Peter Wessel Tordenskiold (in Danish) (1st ed.). København: Aschehoug. ISBN 87-11-11667-6. SELIBR 9501242.

- Bergman, Ernst (1954). Gamla varvet vid Göteborg 1660-1825: historik och beskrivning (in Swedish). Göteborg: Nautic. SELIBR 1434585.

- Ericson Wolke, Lars (1997). Lasse i Gatan: kaparkriget och det svenska stormaktsväldets fall (in Swedish). Lund: Historiska media. ISBN 91-88930-13-0. SELIBR 7776551.

- Feiff, Christer (1998). Fångar och försvarare på Nya Älvsborg (in Swedish). Mölndal: Mölndals bokförl. ISBN 91-630-6325-5. SELIBR 7452613.

- Göteborgs eskader och örlogsstation 1523-1870: historik (in Swedish). Göteborg: Försvarsstabens krigshistoriska avdelning. 1949. SELIBR 418535.

- Kuylenstierna, Oswald (1899). Striderna vid Göta älfs mynning åren 1717 och 1719. Skrifter / Militärlitteraturföreningens förlag, 99-0578882-4 ; 77 (in Swedish). Stockholm: Norstedt. SELIBR 1644371.

- Modig, Nils (2013). Strömstad: gränsstad i ofred och krig. Forum navales skriftserie, 1650-1837 ; 45 (in Swedish). Sävedalen: Warne. ISBN 978-91-85597-37-6. SELIBR 14074652.

- Rothe, Casper Peter (1747–1750). Den danske Söe-Heldt og Vice-Admiral Peder Tordenskjolds omstændelige Livs og Heldte-Levnets Beskrivelse. Forsög til navnkundige danske Mænds Livs og Levnets Beskrivelse ; Stykke 2 (in Danish). 3 volumes. Kiöbenhavn. SELIBR 3016669.

- Sundberg, Ulf (2010). Sveriges krig. D. 3, 1630-1814 (in Swedish). Hallstavik: Svenskt militärhistoriskt bibliotek. ISBN 978-91-85789-63-4. SELIBR 11856268.

- Törnquist, Leif; Gezelius, Malin; Ericson Wolke, Lars (2007). Svenska borgar och fästningar: en historisk reseguide (in Swedish). Stockholm: Medströms. ISBN 978-91-7329-001-2. SELIBR 10485201.