Aurelius Southall Scott | |

|---|---|

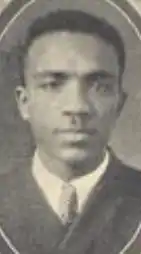

Aurelius Southall Scott, from the 1930 yearbook of Bethune-Cookman College | |

| Born | January 26, 1901 Edwards, Mississippi |

| Died | June 28, 1978 |

| Nationality | American |

| Occupation(s) | Educator, editor, political candidate |

Aurelius Southall Scott (January 26, 1901 – June 28, 1978) was an American educator and newspaper editor. Scott made national headlines in 1946, when he ran for public office in Georgia; he was arrested and institutionalized to force an end to his campaign.

Early life

Aurelius Southall Scott was born in Edwards, Mississippi,[1] one of the nine children of the Rev. William Alexander Scott and Emmeline Southall Scott.[2][3] His father was clergyman and publisher; his mother was a teacher and a typesetter in her husband's publishing business.[4][5] He attended Morehouse College, where he played football and was a member of the debate team, before graduating in 1925.[6] He earned a master's degree at Ohio State University.[7]

Career

Education and publishing

Scott taught at Bethune-Cookman College[8] and West Virginia State University.[1] Scott's brother W. A. Scott Jr. founded the Atlanta Daily World newspaper in 1928;[9] when W. A. Scott Jr. was killed in 1934,[10] his brothers fought over the family's publishing business.[11] Aurelius S. Scott was editor of the Birmingham World newspaper, until another brother, Cornelius A. Scott, fired him after a salary disagreement.[12]

In 1961, Aurelius S. Scott founded the University of Love, an Atlanta-based institute.[13]

Politics and institutionalization

In 1946, Scott ran for Fulton County coroner.[14][15] Fearing that he might become the first black elected official in Georgia since Reconstruction,[16] his white opponents and others (including his brother, editor Cornelius A. Scott) pressured him to withdraw as a candidate.[17][18] When he refused to withdraw,[19] his residency qualification was challenged,[20] and he was arrested, possibly[21] with his brother's cooperation.[22][23] Aurelius Scott reacted violently to the arrest,[24] and was institutionalized at a mental hospital in Nashville, Tennessee,[25] effectively ending his campaign.[26] [27]

Scott's family,[28] the NAACP, the National Urban League, and the American Civil Liberties Union all protested Scott's removal from the ballot and involuntary commitment.[29] "He has done his people great harm," declared the editors of the Atlanta Journal-Constitution, "apparently out of a desire, by no means confined to the Negro race, for publicity, or notoriety."[30] "Criticism should be aimed at the forces facing Scott rather than at him," commented the National Urban League's Lester B. Granger.[31]

Personal life

Scott married fellow professor Mazie O. Tyson in 1928;[32] they ran a summer camp together in Ohio, and were on the faculty together at Bethune-Cookman College,[7] before they separated in the 1930s. He married again in 1943, to Ruth Commons.[33] Scott died in July 1978, aged 77 years.[1]

References

- 1 2 3 "Atlantans Mourn Death of Aurelius S. Scott, 77" Jet (July 27, 1978): 56.

- ↑ "Scott Family, c1928, in the New Georgia Encyclopedia". Georgia Journeys. Retrieved 2020-02-13.

- ↑ "Mother of Atlanta Newspaper Publishers Dies at Age 98". Jet: 55. July 21, 1977.

- ↑ Teel, Leonard Ray (2000). "Scott, William Alexander, II (1902-1934), newspaper publisher". American National Biography Online. Vol. 1. Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/anb/9780198606697.article.1603105. ISBN 978-0-19-860669-7.

- ↑ "Deaths: Emmeline Scott". The Evening Review. 1977-07-06. p. 4. Retrieved 2020-02-13.

- ↑ "Atlanta, the Scott Family, and the Creation of a Media Empire". Atlanta Studies. 2018-12-18. Retrieved 2020-02-13.

- 1 2 The Wildcat (Bethune-Cookman College 1930): 17.

- ↑ Bethune-Cookman University, The Advocate, Catalogue, Edition of 1930-31 (1930): 12.

- ↑ "Photos: Atlanta Daily World and the Scott family". Atlanta Journal-Constitution. Retrieved 2020-02-13.

- ↑ "Brother-in-Law on Trial for Slaying of Ga. Publisher". Baltimore Afro American. February 9, 1935. p. 2. Retrieved February 13, 2020 – via NewspaperArchive.com.

- ↑ "Family Fight for Control of Scott Papers". Baltimore Afro American. May 5, 1934. p. 7. Retrieved February 13, 2020 – via NewspaperArchive.com.

- ↑ "Long-Distance Calls Result in Loss of Job". The Pittsburgh Courier. 1938-11-12. p. 7. Retrieved 2020-02-13 – via Newspapers.com.

- ↑ "People are Talking About". Jet: 46. July 6, 1961.

- ↑ "In Race, Maybe". The Spokesman-Review. 1946-10-13. p. 5. Retrieved 2020-02-13 – via Newspapers.com.

- ↑ "Squeezed Out". The Des Moines Register. 1946-10-12. p. 2. Retrieved 2020-02-13 – via Newspapers.com.

- ↑ "Seeks Georgia Vote". Wisconsin State Journal. 1946-10-18. p. 17. Retrieved 2020-02-13 – via Newspapers.com.

- ↑ "Georgia Democrats Bar Negro in Race, Then Change Minds". Chicago Tribune. 1946-10-12. p. 6. Retrieved 2020-02-13 – via Newspapers.com.

- ↑ "Fresh Wrinkles in Georgia Row". The Spokesman-Review. 1946-10-15. p. 9. Retrieved 2020-02-13 – via Newspapers.com.

- ↑ "Georgia Negro to Remain in Race for Coroner in Atlanta". Amarillo Daily News. 1946-10-15. p. 3. Retrieved 2020-02-13 – via Newspapers.com.

- ↑ Miller, J. Erroll (1948). "The Negro in Present Day Politics With Special Reference to Philadelphia". The Journal of Negro History. 33 (3): 339. doi:10.2307/2715478. ISSN 0022-2992. JSTOR 2715478. S2CID 150016657.

- ↑ "Tales Conflict on Negro Candidate's Move to Hospital". The Gazette. 1946-10-21. p. 2. Retrieved 2020-02-13 – via Newspapers.com.

- ↑ "Atlanta Negro Seeking Office Is Arrested". The Courier-Journal. 1946-10-20. p. 11. Retrieved 2020-02-13 – via Newspapers.com.

- ↑ "Deplores Race". The Knoxville Journal. 1946-10-11. p. 7. Retrieved 2020-02-13.

- ↑ "Candidate Scott Near Institution Treatment". The Atlanta Constitution. 1946-10-19. p. 1. Retrieved 2020-02-13 – via Newspapers.com.

- ↑ "Negro Politico Mental Patient". The Spokesman-Review. 1946-10-20. p. 20. Retrieved 2020-02-13 – via Newspapers.com.

- ↑ "Scott's Name Taken off Ga. County Ticket". Indianapolis Recorder. November 2, 1946. p. 7. Retrieved February 13, 2020 – via Hoosier State Chronicles.

- ↑ Patterson, William L. (1952). We Charge Genocide: The Historic Petition to the United Nations for Relief from a Crime of the United States Government Against the Negro People. Civil Rights Congress. pp. 91–92.

- ↑ "Family Denies Making Charge Against Scott". Indianapolis Recorder. November 2, 1946. Retrieved February 13, 2020 – via Hoosier State Chronicles.

- ↑ "Candidacy of Scott for Ga. Coroner Called Untimely". Jackson Advocate. October 26, 1946. p. 7. Retrieved February 13, 2020 – via NewspaperArchive.com.

- ↑ "The Case of Aurelius S. Scott". The Atlanta Constitution. 1946-10-18. p. 12. Retrieved 2020-02-13 – via Newspapers.com.

- ↑ "Candidate Kicked Out, Record Erased". Baltimore Afro American. October 19, 1946. p. 24. Retrieved February 13, 2020 – via NewspaperArchive.com.

- ↑ "Tyson-Scott Wedding". The Evening Review. 1928-06-16. p. 5. Retrieved 2020-02-13 – via Newspapers.com.

- ↑ "Prominent Couple Feted". The Pittsburgh Courier. 1943-04-10. p. 10. Retrieved 2020-02-13 – via Newspapers.com.

External links

- Aurelius Southall Scott at Find a Grave

- Thomas Aiello, The Grapevine of the Black South: The Scott Newspaper Syndicate in the Generation Before the Civil Rights Movement (University of Georgia Press 2018). ISBN 9-780-8203-5446-0