| Australian pitcher plant | |

|---|---|

| |

| Cephalotus follicularis | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Plantae |

| Clade: | Tracheophytes |

| Clade: | Angiosperms |

| Clade: | Eudicots |

| Clade: | Rosids |

| Order: | Oxalidales |

| Family: | Cephalotaceae |

| Genus: | Cephalotus |

| Species: | C. follicularis |

| Binomial name | |

| Cephalotus follicularis | |

| Synonyms | |

|

Australian pitcher plant, Albany pitcher plant | |

The Australian pitcher plant (Cephalotus follicularis), also known as Albany pitcher plant, is the only species of plant in the Cephalotaceae family and Oxalidales order. It can be found exclusively in moist conditions in a small region in southwest Australia and is considered to be a carnivorous plant. Similar to the not related Nepenthes, it catches its victims with pitfall traps.

Description

Habitus

The Australian pitcher plant is a wintergreen, long lasting, herbaceous plant, which grows autochthonous rosettes and grows up to a height of 10 centimetres.[1]

The rhizome is bulky, nodose with numerous scaly leaves and many offshoots. New rosettes grow at its stolon so that it forms large tussocks with increasing age. The rhizome grows numerous fibrous roots. Younger plants also have a taproot, which dies when they grow older.[2]

Leaves

The Australian pitcher plant grows two kinds of leaves with the change of seasons: simple flat leaves as well as strongly modified trap leaves. Occasionally, there are intermediate forms of leaves with only partially developed traps, lacking the front part.[1] All leaves grow alternating, they are petiolate, with single-celled fine hairs and beset with numerous sessile nectaries.[2]

The form of the flat leaves range from spatulate to reverse ovoid. Additionally, they are pointed and up to 15 centimetres long. Approximately, half of the length of the leaves is allotted to the petiole. They are thick and coriaceaous, the edges are fringed while the leaf surface is smooth and glossy.[1]

Trap leaves

The trap leaves are up to 5 centimeters long, egg-shaped and liquid-filled pitfall traps that are open at the top. They lie on the substrate at an angle of 45° or they are sunk into it in the case of mossy substrates. The petiole is cylindrical and fused to the back of the upper edge of the trap.[3]

Four very hairy ridges on the outside of the traps make it easier for crawling animals to reach the trap opening. The outer skin is completely covered with glands that secrete a liquid, presumably nectar.[2]

A lid over the opening, an outgrowth of the petiole, spans the interior and protects it from rain, which could cause the pitcher fluid to overflow and wash out dead prey.[3] It is curved, notched and ciliated at the edge, lacking a midrib. The inside is covered with short, downward-pointing hairs.[1] The lid is alternately divided into white-translucent and dark red sections without chlorophyll. The translucent sections appear window-like, through which trapped flying insects try to escape, only to fall back into the pitchers afterwards.[4]

The inwardly overhanging, thickened edge of the trap is surrounded by large, inward-pointing, claw-like teeth in between nectar glands. Immediately adjacent to this is an area of short, downward-facing papillae that make it difficult to climb back up. The rest of the inner wall of the cauldron is smooth, so that the prey slips into the trap and cannot climb out of it.[1]

The upper third, or the upper half of the trap leaf, is finely beset with glands. In the lower part of the trap there are two kidney-shaped, red-coloured spots that are densely covered with larger glands. These glands most likely produce the liquid in the can, as well as the digestive enzymes and also absorb the nutrients from the prey.[4]

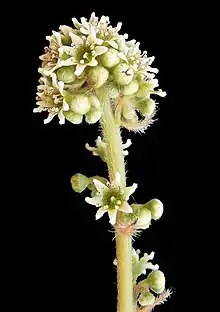

Blossoms, fruit and seeds

Stipules are missing. The single flower stalk appears at the beginning of the Australian summer (flowering time: January–February) and is up to 60 centimetres long, with a panicle at its end. Each of the secondary axes bears up to four or five white, upright, six-cornered flowers, which are up to 7 millimeters in diameter. There are missing petals and the six carpels are not fused. Flowers sag when they are fertilized. The spadiciform[3] leathery, hairy follicle fruits and contain one or two brown, ovoid seeds with a membranous testa and rich, granular endosperm.[2] The seeds are 0.8 millimetres long and 0.4 millimetres wide. The germination only occurs if the seed remains in the fruit.[3]

Cytology and constituents

The chromosome number is 2n = 20. Tannin cells are present as well as myricetin, quercetin, ellagic acid,gallic acid. However, iridoids are absent.[2]

Ecology

The flowers are pollinated by small insects, more precise information is not available. The plants survive occasional bush fires in the undergrowth by sprouting again from the rhizome. However, the seeds are not pyrophytes.[2]

Carnivore

After the pitcher is formed, the lid lifts from the peristome and the pitcher is ready to catch. Digestive fluid is already in the pitcher. The prey is attracted by nectar secretions on the bottom of the pitcher lid and between the grooves of the pitcher rim. This causes the prey to fall in and drown. The liquid contains enzymes that break down the nutrients, including esterases, phosphatases and proteases. In the majority of cases, ants are caught.[1]

Traps as biotopes

As with all other carnivorous plant species with sliding traps, the trap fluid is also a biotope for other organisms. A study published in 1985 counted 166 different species, including 82% protozoa, 4% oligochaeta and nematodes, 4% arthropods (copepods, diptera and mites), 2% rotifers, 1% tardigrades and 7% others (bacteria, fungi, algae). Bacteria and fungi in particular also secrete digestive enzymes and thus support the plant's digestive process. It is particularly noticeable that the traps are the "nursery" of two species of diptera. In addition to the larvae of a Dasyhelea species, the larvae of the micropezidae Badisis ambulans also live in the cans.[5]

Distribution and Endangerment

The plant is endemic to the southwest of Australia, in the coastal area northeast of Albany in a zone of around 400 kilometres between Augusta and Cape Riche. It is mainly found in cushions of Sphagnum on consistently moist but well-drained, acidic peat soils over granite, in seeping areas, along riverbanks or under so-called tussocks, grasses that grow in clumps (z. B. from Restionaceae).[2]

The Australian pitcher plant is categorised as endangered[6] by the IUCN due to its restricted distribution. However, there is no acute threat. Because parts of its distribution area are protected and the plants are common within this, they have been removed from CITES-Appendix II.[2]

Botanical Systematics

The genus as well as the family Cephalotaceae include only this one species, which means they are monotypic. The Cunoniaceae are their nearest relations.[2]

Brocchinia reducta and the Australian pitcher plant are the only carnivorous plants that are not part of the orders of Lamiales, Caryophyllales or Ericales and therefore not even indirectly related to other carnivorous plants.

Botanical History

The Australian pitcher plant was possibly already discovered in 1791 on the expedition by the botanist Archibald Menzies. The plant was first described in 1806 by Jacques Julien Houtton de La Billardière. In 1800 Robert Brown had already observed the species while catching insects. Since 1823 specimens of the plant have been cultivated in the botanic garden Kew Gardens. In 1829 Dumortier categorised the species in its own monotypic family, which is still valid today.[1]

Due to the form of the anther La Billardière uses the Greek term kefalotus ("to have a head") for the genus. Follicularis derives from follicus, meaning "small sack", and refers to the form of the jars. The Australian pitcher plant is also called Albany Pitcher Plant or Western Australian Pitcher Plant.[1]

Uses

The Australian pitcher plant is popular with enthusiasts of carnivorous plans and cultivated worldwide[2] – however, its cultivation is considered challenging.[7][8]

References

Footnotes directly behind a statement prove the individual statement, footnotes directly behind a punctuation prove the whole preceding sentence. Footnotes behind a space prove the whole preceding text.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 Wilhelm Barthlott, Stefan Porembski, Rüdiger Seine, Inge Theisen: Karnivoren. Biologie und Kultur fleischfressender Pflanzen. Ulmer, Stuttgart 2004, ISBN 3-8001-4144-2, S. 87–90.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 John G. Conran: Cephalotaceae. In: Klaus Kubitzki: (Hrsg.): The Families and Genera of Vascular Plants. Volume 6: Flowering Plants – Dicotyledons – Celastrales, Oxalidales, Rosales, Cornales, Ericales. Springer, Berlin u. a. 2004, ISBN 3-540-06512-1, S. 65–69.

- 1 2 3 4 Allen Lowrie: Carnivorous Plants of Australia. Band 3. University of Western Australia Press, Nedlands 1998, ISBN 1-875560-59-9, S. 128–131.

- 1 2 Francis Ernest Lloyd: The Carnivorous Plants (= A New Series of Plant Science Books. 9, ZDB-ID 415601-8). Chronica Botanica Company, Waltham MA 1942, S. 81–89, (Nachdruck: Dover, New York NY 1976, ISBN 0-486-23321-9).

- ↑ David Yeates: Immature stages of the apterous fly Badisis ambulans McAlpine (Diptera: Micropezidae). In: Journal of Natural History. Bd. 26, Nr. 2, 1992, ISSN 0022-2933, S. 417–424, doi:10.1080/00222939200770241.

- ↑ Cephalotus follicularis in der Roten Liste gefährdeter Arten der IUCN 2007. Eingestellt von: Conran, J.G., Lowrie, A. & Leach, G., 2000. Abgerufen am 11. Mai 2008..

- ↑ Peter D'Amato: The savage garden. Cultivating carnivorous plants. Ten Speed Press, Berkeley CA 1998, ISBN 0-89815-915-6.

- ↑ Jean-Jacques Labat: Fleischfressende Pflanzen. Auswählen und pflegen. Ulmer, Stuttgart 2003, ISBN 3-8001-3582-5.