| Austroplatypus incompertus | |

|---|---|

| |

| Scientific classification | |

| Domain: | Eukaryota |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Arthropoda |

| Class: | Insecta |

| Order: | Coleoptera |

| Infraorder: | Cucujiformia |

| Family: | Curculionidae |

| Subfamily: | Platypodinae |

| Tribe: | Platypodini |

| Genus: | Austroplatypus |

| Species: | A. incompertus |

| Binomial name | |

| Austroplatypus incompertus (Schedl, 1968) | |

Austroplatypus incompertus is a species of ambrosia beetle belonging to the true weevil family, native to Australia, with a verified distribution in New South Wales and Victoria.[1] It forms colonies in the heartwood of Eucalyptus trees and is the first beetle to be recognized as a eusocial insect.[2][3] Austroplatypus incompertus is considered eusocial because groups contain a single fertilized female that is protected and taken care of by a small number of unfertilized females that also do much of the work.[4] The species likely passed on cultivated fungi to other weevils.[5]

Description and life cycle

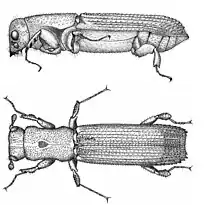

The egg of A. incompertus is about 0.7 mm in length and 0.45 mm wide. It develops through five instars and its head grows from around 0.3 mm wide in the first instar to 0.9 mm wide in the fifth instar. It then pupates and emerges as an adult - 6 mm long and 2 mm wide. The adult has an elongated, cylindrical body typical of other platypodines, and displays sexual dimorphism, with males being the significantly smaller sex, an atypical arrangement among platypodine beetles. Females have elytral declivity adapted for cleaning of galleries and defense. Also, only females exhibit mycangia.[6]

Habitat

Like other ambrosia beetles, A. incompertus lives in nutritional symbiosis with ambrosia fungi. They excavate tunnels in living trees in which they cultivate fungal gardens as their sole source of nutrition. New colonies are founded by fertilized females that use special structures called mycangia to transport fungi to a new host tree.[7] The mycangia of A. incompertus and the specific manner in which the species acquires fungal spores for transport have been studied and compared with the mechanisms used by other ambrosia beetles.[3] Fertilized females begin tunneling into trees in the autumn and take about seven months to penetrate 50 to 80 mm deep to lay their eggs.[2][3]

Host trees

An assessment done by the United States Department of Agriculture (USDA) on unprocessed logs and chips of 18 woody-plant species from Australia discovered A. incompertus in most of them, including: Eucalyptus baxteri, E. botryoides, E. consideniana, E. delegatensis, E. eugenioides, E. fastigata, E. globoidea, E. macrorhyncha, E. muelleriana, E. obliqua, E. pilularis, E. radiata, E. scabra, E. sieberi, and Corymbia gummifera. Unlike most ambrosia beetles, it infests healthy, undamaged trees.[8]

Distribution

A. incompertus is local to Australia, and has been confirmed to be found in various places around New South Wales. Their range is somewhat limited, extending from Omeo in Victoria and Eden in NSW north to Dorrigo and west to the Styx River State Forest in Northern NSW.[9]

Behavior

Social structure

A fertilized female attempts to start a new colony by burrowing deep into the heart of a living tree, eventually branching off and depositing her fungal spores and larvae.[2] When these larvae grow to adulthood, the males leave some time before the females, with an average of five females remaining behind, which quickly lose the last four tarsal segments on their hind legs.[3][10] The sole entrance to the colony shortly thereafter will be closed by the tree, enclosing the colony. This deformity and physical barrier causes females to remain unfertilized and they participate in maintenance, excavation, and defense of the galleries, propagating the maintenance of the social hierarchy.[10]

Eusociality

A. incompertus is one of the few organisms outside of Hymenoptera (bees and ants) and Isoptera (termites) to exhibit eusociality. Eusocial insects develop large, multigenerational cooperative societies that assist each other in the rearing of young, often at the cost of an individual’s life or reproductive ability. As a result, sterile castes within the colony perform nonreproductive work. This altruism is explained because eusocial insects benefit from giving up reproductive ability of many individuals to improve the overall fitness of closely related offspring.

For an animal to be considered eusocial, it must satisfy the three criteria defined by E. O. Wilson.[11] The species must have reproductive division of labor. A. incompertus contains a single fertilized female that is guarded by a small number of unfertilized females that also do much of the work excavating galleries in the wood, satisfying the first criterion. The second criterion requires the group to have overlapping generations, a phenomenon found in A. incompertus. Finally, A. incompertus exhibits cooperative brood care, the third criterion for eusociality.[12]

Hypotheses for evolution of eusociality

The reasons behind the evolution of eusociality in these weevils are unclear.[3][13] The benefits to being altruistic come in two ecological modes: “life insurers” and “fortress defenders”.[14] Most Hymenoptera, the large majority of social insects, are life insurers, where eusociality is adapted as a safeguard from decreased life expectancy of offspring. Most termites, as fortress defenders, benefit from working together to best exploit a valuable ecological resource.[14]

From A. incompertus' ecology, fortress defense is likely considering they excavate wood galleries in host trees with just a single entrance. Fortress defense is sufficient to evolve eusociality when three criteria are met: food coinciding with shelter, selection for defense against intruders and predators, and the ability to defend such a habitat.[15] The female that begins the colony bring the weevils' source of food, its symbiotic fungi, to rest in the wood galleries that it excavates.[3] This satisfies the first criterion. Females exhibit noticeably prominent spines on their elytra, and females are the only sex to defend the galleries, possibly satisfying the second criterion.[3] The third criterion is insufficiently studied and demonstrated. The single entrance could potentially show ability to defend, though several commensals and at least one predator have been found residing in colonies.[3]

Successful eusocial A. incompertus colonies do better reproductively than their nonhelping counterparts.[3] This could follow the "life insurer" possibility in that benefits to the offspring of a related individual would increase the desire to assist that individual and have a better chance of gene propagation through kin selection. Hymenopterans that follow such life patterns have a sex determination system where, while the females are diploid and pass down only 50% of their genes due to chromosomal crossover during oogenesis, the males are haploid and pass down their entire genome unaltered. This haplodiploidy hypothesis holds that eusociality evolved because diploid sisters are more related to future sisters than they would be to their own offspring.[16] This hypothesis does not hold up for A. incompertus, however, as a study of genetic markers has shown that all adults, male and female, reproductive or worker, are diploid.[13]

It is entirely possible that this organism evolved eusociality and altruistic behaviors in a different manner from those studied in other species, as it is the first in the order Coleoptera to show such behavior.[12] A. incompertus inhabiting a live tree as opposed to a dead one may be the cause for such behaviors.[13] Success of colonies in this species is relatively low (12%[3]) because it is difficult to occupy the living tissue of the trees and initial success of the fertilized female is challenged by an arduous set-up phase. This has led to the hypothesis that eusociality in colonies with a single female assists in maximizing offspring of a related individual.[3] Relatedness of worker females has not been established, however, and it is unclear that eusociality would be able to evolve simply because of this fact.[13] A further expansion of this hypothesis is that given difficulty of colony founding, helper females may remain in hopes of inheriting the colony.[3] Inhabiting a living tree may offer a much more expansive and sustainable colony for the weevil, but doing so requires maintenance of the galleries from a hostile source environment.[13] It is still unclear if the above reasons are enough to have evolved such behavior in the first place, and discovery of monogamy in the species might further lend to the kin selection hypothesis.[13] Understanding sociality in this group is of great importance in the study of the evolution of such systems, given its unique nature in a far-removed organism.[12]

See also

- Passalidae, an unrelated family of beetles that also live in wood and show sociality

References

- ↑ "Australian Government Department of Agriculture, Fisheries and Forestry". Ento.csiro.au. Retrieved 2010-10-31.

- 1 2 3 "Science: The Australian beetle that behaves like a bee". New Scientist. 1992-05-09. Retrieved 2010-10-31.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 D. S. Kent & J. A. Simpson (1992). "Eusociality in the beetle Austroplatypus incompertus (Coleoptera: Curculionidae)". Naturwissenschaften. 79 (2): 86–87. Bibcode:1992NW.....79...86K. doi:10.1007/BF01131810. S2CID 35534268.

- ↑ "Sociable Beetles;". Nature. 356 (6365): 111. 1992. Bibcode:1992Natur.356R.111.. doi:10.1038/356111c0. S2CID 4338288.

- ↑ Vanderpool, Dan; Bracewell, Ryan R.; McCutcheon, John P. (2018). "Know your farmer: Ancient origins and multiple independent domestications of ambrosia beetle fungal cultivars". Molecular Ecology. 27 (8): 2077–2094. doi:10.1111/mec.14394. ISSN 1365-294X. PMID 29087025.

- ↑ Kent, D. S. (2010). "The external morphology of Austroplatypus incompertus (Schedl) (Coleoptera, Curculionidae, Platypodinae)". ZooKeys (56): 121–140. doi:10.3897/zookeys.56.521. PMC 3088331. PMID 21594175.

- ↑ Kent, Deborah S. (2008). "Mycangia of the ambrosia beetle, Austroplatypus incompertus (Schedl) (Coleoptera: Curculionidae: Platypodinae)". Australian Journal of Entomology. 47 (1): 9–12. doi:10.1111/j.1440-6055.2007.00612.x.

- ↑ "Pest Risk Assessment of the Importation Into the United States of Unprocessed Logs and Chips of Eighteen Eucalypt Species From Australia, United States Department of Agriculture, Forest Service, Forest Products Laboratory, General Technical Report FPL−GTR−137" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 2012-03-08. Retrieved 2010-10-31.

- ↑ Kent DS. (2008a) Distribution and host plant records of Austroplatypus incompertus (Schedl) (Coleoptera: Curculionidae: Platypodinae). Australian Entomologist 35 (1):1-6.

- 1 2 Kent, D (2002). "Biology of the ambrosia beetle Austroplatypus incompertus (Schedl)". Australian Journal of Entomology. 41 (4): 378. doi:10.1046/j.1440-6055.2002.00314.x.

- ↑ [Wilson, E. O. 1971: The insect societies. — Belknap Press of Harvard University Press. Cambridge. Massachusetts.]

- 1 2 3 "Sociable Beetles;". Nature. 356 (6365): 111. 1992. Bibcode:1992Natur.356R.111.. doi:10.1038/356111c0. S2CID 4338288.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 [ Ploidy of the eusocial beetle Austroplatypus incompertus (Schedl) (Coleoptera, Curculionidae) and implications for the evolution of eusociality]

- 1 2 Kin selection and social insects

- ↑ Three conditions for the evolution of eusociality: Are they sufficient?

- ↑ Hamilton, W. D. (July 1964). "The Genetical Evolution of Social Behaviour II". Journal of Theoretical Biology. 7 (1): 17–52. doi:10.1016/0022-5193(64)90039-6. PMID 5875340.