| Avigliana Castle | |

|---|---|

Castello di Avigliana | |

| Avigliana, Turin, Piedmont, | |

The ruins of Avigliana Castle on Mount Pezzulano | |

Avigliana Castle | |

| Coordinates | 45°04′22″N 7°23′37″E / 45.07278°N 7.39361°E |

| Type | Medieval castle |

| Site information | |

| Condition | Ruin |

| Site history | |

| Built | 924 |

| Built by | Arduin Glaber |

| Demolished | 1691 |

Avigliana Castle is one of the oldest castles in Piedmont (reputedly dating back to the 10th century). Now just a ruin, it is located in Avigliana at the mouth of the Susa Valley, 25 km from Turin.

Location

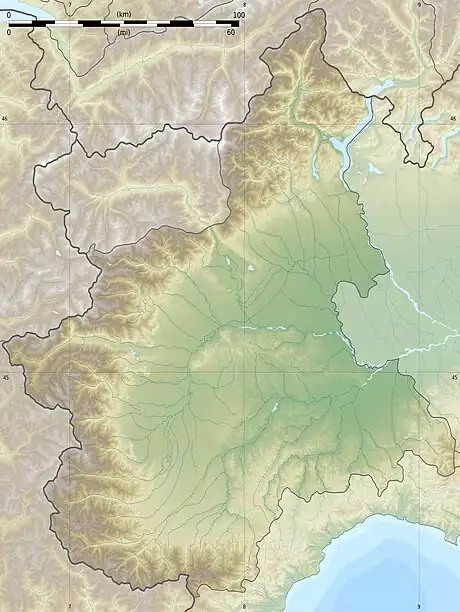

The castle is located on the summit of Mount Pezzulano (467 m a.s.l.) just above the town of Avigliana.[1] It lies a short distance from Avigliana's medieval town centre (Piazza Conte Rosso). It overlooks the Avigliana lakes (especially Lago Grande), the morainic hill of Rivoli and the famous Sacra di San Michele.

History

It is said that Cleph, king of the lombards, built the earliest fortification on the Pezzulano peak in 574,[2] but the earliest mention of the current structure is in 924 under the margrave of Turin Arduin Glaber. With its mighty bulk and high towers,[3] it expanded rapidly thanks to its position (it was the last stronghold before Turin for those invading from France), undergoing frequent assaults and much looting over the centuries.

11th & 12th centuries

The earliest mention of a castrum Avilianae dates back to 961.[1] It is first documented in the marginalia of a chronicle dated between 1058 and 1061 concerning the foundation of the Sacra di San Michele. The chronicler mentions that the margrave Arduin V used to reside in the castle of Avigliana. This stronghold also performed an important defensive function as a base during the 10th century in the long fight against the Saracen invasion of north-western Italy.[3]

In 1137, the building is documented as being one of the favourite seats[3] of Amadeus III, Count of Savoy when he resided on this side of the Alps (the Counts of Savoy had only acquired Piedmont in 1091 through the dowery of the margravine Adelaide of Susa). It was the base for his expansion towards Turin in the following century. Humbert III of Savoy, Amadeus III's son and heir, was born there on 4 August 1136.

Avigliana was a significant source of revenue for the Savoy family as it stood on a popular merchant route to France and Flanders and was a source of tolls.[2]

When there were no counts in residence, the castle of Avigliana was the permanent seat of a castellan (appointed by the count) who administered the surrounding territory on behalf of his master, who in turn was a feudal lord of the Holy Roman Emperor.

Frederick Barbarossa destroyed the castle during his descent into Italy, together with the surrounding villages of Ferronia and Pagliarino,[3] and it was later rebuilt by Thomas I of Savoy.

Over the course of three centuries, the castle was established as one of the count's main command centres, resulting in the growth of an urban settlement at the foot of the hill on which it stood.

Nothing is known about the construction of the castrum at the end of the 10th century and very little about the following two centuries. In the 11th century, the castle and village comprised basic layout of a fortified hilltop with an adjacent older settlement lining the Via Francigena that passed on the northern side of the rocky protuberance of Mount Pezzulano.

13th & 14th centuries

The structure that emerges from documents of the 13th and 14th centuries shows an irregularly ellipsoidal enclosure that follows the contours of the natural relief. The castle comprises a residential wing with a chapel, leaning against the eastern side, a massive square central tower and a semi-circular false tower in the southern corner. During the 13th century, the castle gate, a pit and an oven are mentioned, as are wooden shingle and tile roofs. In 1212, the castle chapel, dedicated to St. Mary Magdalene, is mentioned. In 1268, an aula castri, or courtroom, is mentioned for the first time, and in 1307 a sala castri is positioned next to the courtroom and intended for both social life and formal government.[1]

Fourteenth-century documents testify to a multi-storey residential wing with reception rooms and a chapel at the upper levels and service rooms and cellars on the ground floor. This wing overlooked an upper inner courtyard with stables, a bread oven and the granerium, used to store the proceeds in kind from the payment of banna (taxes).[1]

On 24 February 1360, Amedeo VII Count of Savoy, known as the Red Count, was born here, and in 1368 Phillip II of Piedmont, the rebel prince who had ruled Turin on behalf of the Green Count (who whose court was based on the other side of the Alps) was imprisoned there while awaiting a sentence of death by drowning in the Lake of Avigliana.

15th century onwards

In August 1449, the old castle saw the birth of Bona of Savoy, future wife of the powerful Duke of Milan Galeazzo Maria Sforza.[3]

Following the death of Amedeo VIII, Duke of Savoy, in 1451 there were five successors in a period of half century, culminating in Philip II. Philip had allowed the French troops of Louis XII access through the Susa Valley to access Lombardy, but not without problems, so his successor, Charles III, closed the borders and Francis I, now king of France, sent in a task force under marshal De Montmorency. In 1536, after conquering the town of Susa, the French army partially destroyed the castle with cannon fire.[2]

After the period of splendour of the Savoy court, from the 15th century until its destruction, the castle was simply a fortress in the lower Susa Valley. Often damaged and then rebuilt, most recently by Amedeo di Castellamonte in 1655, the castle was finally destroyed using mines by the French troops of Marshal Catinat in May 1691. It no longer needed be rebuilt due to the construction of the new Savoy forts of Brunetta di Susa in 1708 (demolished at the end of the 18th century) and Fort of Exilles.[3]

In 1882, Marquis Gerardo di S. Tommaso donated the castle ruins to the municipality, and they were restored ten years later. In 1927, the ruins were included in the 'parco del littorio', planted with black pines, while the last wartime use dates back to the Second World War.[1]

All that remains today are the ruins of the old manor house and the panoramic view.

Legends

It is said that during the final battle, some French soldiers sneaked into the orderly room and stole a chest containing the officers' pay and made off with it, burying the loot in a grove to the right of the castle entrance where it might still be found today. Legend also tells of a large boulder bearing an arrow indicating the direction in which to look for the treasure.

Because of its evocativeness, the area near the ruins is full of spectral 'apparitions'; it is also said that Philip II of Savoy-Achaia was imprisoned in this manor and after he drowned his soul still hovers over the surface of the lakes.

Source:[3]

Location

The castle is located on the summit of Mount Pezzulano (467 m a.s.l.) just above the town of Avigliana, and is easily reached from Avigliana's medieval town centre (Piazza Conte Rosso) via a short path. It offers an excellent vantage point over the Avigliana lakes (especially Lago Grandee), the morainic hill of Rivoli and the famous Sacra di San Michele.

See also

References

- 1 2 3 4 5 "Il castello di Avigliana" [The Castle of Avigliana] (PDF). Susa Valley Treasures (in Italian). Soprintendenza per i Beni Archeologici del Piemonte e del MAE. 2010. Retrieved 27 February 2023.

- 1 2 3 Luppi, Vitória (29 April 2020). Reconstruction of the Castle of Avigliana (LM thesis). Politecnico Milano.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 Curino, Luciano (8 June 1992). "Avigliana, torri contro i Saraceni". La Stampa. p. 23. Retrieved 27 February 2023.

Bibliography

Various Authors (1996). Il Piemonte paese per paese (in Italian). Vol. 1. Firenze: Casa Editrice Bonechi. ISBN 9788880291565.

External links

- "Città di Avigliana Home page". Retrieved 27 February 2023.