| Amel-Marduk | |

|---|---|

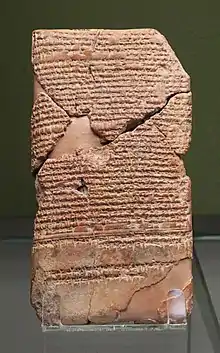

The tablet recording the plea by the jailed prince Nabu-shum-ukin, probably the future Amel-Marduk | |

| King of the Neo-Babylonian Empire | |

| Reign | 7 October 562 BC – August 560 BC |

| Predecessor | Nebuchadnezzar II |

| Successor | Neriglissar |

| Died | August 560 BC Babylon |

| Issue | Indû |

| Akkadian | Amēl-Marduk |

| Dynasty | Chaldean dynasty |

| Father | Nebuchadnezzar II |

| Mother | Amytis of Babylon (?) |

Amel-Marduk (Babylonian cuneiform: ![]() Amēl-Marduk,[1] meaning "man of Marduk"),[1] also known as Awil-Marduk,[2] or under the biblical rendition of his name, Evil-Merodach[1] (Biblical Hebrew: אֱוִיל מְרֹדַךְ, ʾĔwīl Mərōḏaḵ), was the third king of the Neo-Babylonian Empire, ruling from 562 BC until his overthrow and murder in 560 BC. He was the successor of Nebuchadnezzar II (r. 605–562 BC). On account of the small number of surviving cuneiform sources, little is known of Amel-Marduk's reign and actions as king.

Amēl-Marduk,[1] meaning "man of Marduk"),[1] also known as Awil-Marduk,[2] or under the biblical rendition of his name, Evil-Merodach[1] (Biblical Hebrew: אֱוִיל מְרֹדַךְ, ʾĔwīl Mərōḏaḵ), was the third king of the Neo-Babylonian Empire, ruling from 562 BC until his overthrow and murder in 560 BC. He was the successor of Nebuchadnezzar II (r. 605–562 BC). On account of the small number of surviving cuneiform sources, little is known of Amel-Marduk's reign and actions as king.

Amel-Marduk, originally named Nabu-shum-ukin, was not Nebuchadnezzar's eldest son, nor the oldest living son at the time of his appointment as crown prince and heir. It is not clear why Amel-Marduk was appointed by his father as successor, particularly since there appear to have been altercations between the two, possibly involving an attempt by Amel-Marduk to take the throne while his father was still alive. After the conspiracy, Amel-Marduk was imprisoned, possibly together with Jeconiah, the captured king of Judah. Nabu-shum-ukin changed his name to Amel-Marduk upon his release, possibly in reverence of the god Marduk to whom he had prayed.

Amel-Marduk is remembered mainly for releasing Jeconiah after 37 years of imprisonment. Amel-Marduk is also known to have conducted some building work in Babylon, and possibly elsewhere, though the extent of his projects is unclear. The Babylonians appear to have resented his rule, as Babylonian sources from after his reign describe him as incompetent. In 560 BC, he was overthrown and murdered by his brother-in-law Neriglissar who thereafter ruled as king.

Background

Amel-Marduk was the successor of his father, Nebuchadnezzar II (r. 605–562 BC).[1] It seems that the succession to Nebuchadnezzar was troublesome and that the king's last years were prone to political instability.[3] In one of the inscriptions written very late in his reign, after Nebuchadnezzar had already ruled for forty years, the king affirms that he had been chosen for kingship by the gods before he had even been born. Stressing divine legitimacy in such a fashion was usually only done by usurpers, or if there were political problems with his intended successor. Given that Nebuchadnezzar had been king for several decades, and had been the legitimate heir of his predecessor, the first option seems unlikely.[4]

Amel-Marduk was chosen as heir during his father's reign[5] and is attested as crown prince in 566 BC.[6] Amel-Marduk was not Nebuchadnezzar's oldest son—another of Nebuchadnezzar's sons, Marduk-nadin-ahi, is attested in Nebuchadnezzar's third year as king (602/601 BC) as an adult in charge of his own lands.[7] Given that Amel-Marduk is attested considerably later, it is probable that Marduk-nadin-ahi was Nebuchadnezzar's eldest son and legitimate heir,[7] making the reason for the selection of Amel-Marduk unclear, particularly since Marduk-nadin-ahi is attested as living until as late as 563 BC.[8] Additionally, evidence of altercations between Nebuchadnezzar and Amel-Marduk makes his selection as heir seem even more improbable.[5] In one text, Nebuchadnezzar and Amel-Marduk are both implicated in some kind of conspiracy, with one of the two accused of bad conduct against the temples and people:[5]

Concerning [Nebu]chadnezzar they thought [. . .] his life were not treasured [by them . . . the people of] Babylon to Amēl-Marduk spoke, not [. . .] . . . "concerning the treasure of [the Esagila] and Babylon [. . ."] they mentioned the cities of the great gods [. . .] his heart over son and daughter will not let [. . .] family and tribe are [not . . .] in his heart. All that is full [. . .] his thoughts were not about the well-being of [the Esagila and Babylon . . .], with attentive ears he went to the holy gates [. . .] prayed to the Lord of lords [. . .] he cried bitterly to Marduk, the gods [..w]ent his prayer to [. . .].[9]

The inscription contains accusations, though it is unclear to whom they are directed, concerning the desecration of holy places and the exploitation of the populace—failures in the two main responsibilities of the king of Babylon. The accused is afterwards stated to have cried and prayed to Marduk, Babylon's national deity.[10]

Another text from late in Nebuchadnezzar's reign contains a prayer by an imprisoned son of Nebuchadnezzar named Nabu-shum-ukin (![]() Nabû-šum-ukīn), who states that he was imprisoned because of a conspiracy against him.[10] According to the Leviticus Rabbah, a 5th–7th-century AD Midrashic text, Amel-Marduk was imprisoned by his father alongside the captured Judean king Jeconiah (also known as Jehoiachin) because some of the Babylonian officials had proclaimed him king while Nebuchadnezzar was away.[1] The Assyriologist Irving Finkel argued in 1999 that Nabu-shum-ukin was the same person as Amel-Marduk, who changed his name to "man of Marduk" once he was released as reverence towards the god to whom he had prayed.[10][1] Finkel's conclusions have been accepted as convincing by other scholars,[10][1] and would also explain the previous text, perhaps relating to the same incidents.[10] The Chronicles of Jerahmeel, a Hebrew work on history possibly written in the 12th century AD, erroneously states that Amel-Marduk was Nebuchadnezzar's eldest son, but that he was sidelined by his father in favour of his brother, 'Nebuchadnezzar the Younger' (a fictional figure not attested in any other source), and was thus imprisoned together with Jeconiah until the death of Nebuchadnezzar the Younger, after which Amel-Marduk was made king.[11]

Nabû-šum-ukīn), who states that he was imprisoned because of a conspiracy against him.[10] According to the Leviticus Rabbah, a 5th–7th-century AD Midrashic text, Amel-Marduk was imprisoned by his father alongside the captured Judean king Jeconiah (also known as Jehoiachin) because some of the Babylonian officials had proclaimed him king while Nebuchadnezzar was away.[1] The Assyriologist Irving Finkel argued in 1999 that Nabu-shum-ukin was the same person as Amel-Marduk, who changed his name to "man of Marduk" once he was released as reverence towards the god to whom he had prayed.[10][1] Finkel's conclusions have been accepted as convincing by other scholars,[10][1] and would also explain the previous text, perhaps relating to the same incidents.[10] The Chronicles of Jerahmeel, a Hebrew work on history possibly written in the 12th century AD, erroneously states that Amel-Marduk was Nebuchadnezzar's eldest son, but that he was sidelined by his father in favour of his brother, 'Nebuchadnezzar the Younger' (a fictional figure not attested in any other source), and was thus imprisoned together with Jeconiah until the death of Nebuchadnezzar the Younger, after which Amel-Marduk was made king.[11]

Considering the available evidence, it is possible that Nebuchadnezzar saw Amel-Marduk as an unworthy heir and sought to replace him with another son. Why Amel-Marduk nevertheless became king is not clear.[3] Regardless, Amel-Marduk's administrative duties probably began before he became king, during the last few weeks or months of his father's reign when Nebuchadnezzar was ill and dying.[1] The last known tablet dated to Nebuchadnezzar's reign, from Uruk, is dated to the same day, 7 October, as the first known tablet of Amel-Marduk, from Sippar.[12]

Reign

_Den_Grooten_Emblemata_Sacra%252C_bestaande_in_meer_dan_vier_hondert_bybelsche_figuren%252C_zoo_des_Ouden_als_des_Nieuwen_Test%252C_RP-P-2015-10-136.jpg.webp)

Very few cuneiform sources survive from Amel-Marduk's reign,[13] and as such, almost nothing is known of his accomplishments.[1] Despite being the legitimate successor of Nebuchadnezzar, Amel-Marduk was seemingly met with opposition from the very beginning of his rule, as indicated by the brevity of his tenure as king and by his negative portrayal in later sources. The later Hellenistic-era Babylonian writer and astronomer Berossus wrote that Amel-Marduk "ruled capriciously and had no regard for the laws" and a cuneiform propaganda text states that he neglected his family, that officials refused to carry out his orders, and that he solely concerned himself with veneration and worship of Marduk.[1] Whether the opposition towards Amel-Marduk resulted from his earlier attempt at conspiracy against his father, tension between different factions of the royal family (given that he was not the oldest son), or from his own mismanagement as king, is not certain.[8] Little is known of Amel-Marduk's own immediate family, i.e., his wife and potential children. No sons of Amel-Marduk are known,[14] but he had at least one daughter named Indû.[14][15][16] The Chronicles of Jerahmeel ascribes three sons to Amel-Marduk: Regosar, Lebuzer Dukh and Nabhar, though it seems the author confused Amel-Marduk's successors for his sons (respectively, Neriglissar, Labashi-Marduk and Nabonidus).[17]

One of his inscriptions suggests that he renovated the Esagila in Babylon, and the Ezida in Borsippa, but no concrete archaeological or textual evidence exists to confirm that work was actually done at these temples. Some bricks and paving stones in Babylon bear his name, indicating that some building work was completed at Babylon during his brief tenure as king.[1]

The Bible states that Amel-Marduk freed Jeconiah, king of Judah, after 37 years of imprisonment in Babylon, the only concrete political act attributed to Amel-Marduk in any extant source.[1] Though such acts of clemency are known from accession ceremonies, and in this case may have been connected to the celebration of the Babylonian New Year's Festival,[14] the specific reason for Jeconiah's release is not known. Suggested reasons include to win favour with the population of Jewish deportees in Babylonia, or that Amel-Marduk and Jeconiah may have become friends during their imprisonment.[1] Later Jewish tradition held that the release was a deliberate reversal of Nebuchadnezzar's policy (having destroyed the Kingdom of Judah), though there is no indication that Amel-Marduk made any attempt to restore Judah.[14] Despite this, Jewish contemporaries of Amel-Marduk likely hoped that Jeconiah's release was the first step in a restoration of Judah, given that Amel-Marduk also released Baalezer, the captured king of Tyre, and restored him to his throne.[18] The release of Jeconiah is narrated in 2 Kings 25:27–30,[19] and in the Chronicles of Jerahmeel,[14] both sources referring to Amel-Marduk as Evil-Merodach.[19][14] The Chronicles of Jerahmeel narrates the release of Jeconiah as follows:[14]

In the thirty-seventh year of the exile of Jehoiachin king of Judah, in the year Evil-Merodach became king of Babylon, he released Jehoiachin from prison on the twenty-fifth day of the twelfth month. He spoke kindly to him and gave him a seat of honour higher than those of the other kings who were with him in Babylon.[14]

Amel-Marduk's reign abruptly ended in August 560 BC,[20][21] after barely two years as king,[7] when he was deposed and murdered by Neriglissar, his brother-in-law, who then claimed the throne.[20] The last document from the reign of Amel-Marduk is a contract dated to 7 August 560 BC, written in Babylon. Four days later, documents dated to Neriglissar are known from both Babylon and Uruk. Based on increased economic activity attributed to him in the capital, Neriglissar was at Babylon at the time of the usurpation.[21] It is likely that the conflict between Amel-Marduk and Neriglissar was a result of inter-family discord rather than some other form of rivalry.[21] Neriglissar was married to one of Nebuchadnezzar's daughters, possibly Kashshaya. As Kashshaya is attested considerably earlier in Nebuchadnezzar's reign than Amel-Marduk (in Nebuchadnezzar's fifth year, 600/599 BC) and most of the other sons, it is possible that she was older than them.[22] Though the gap between the earliest reference to Kashshaya and those of the sons could be accidental or coincidental;[23] it could also be interpreted as an indication that many of the sons were the progeny of a second marriage. It is therefore possible that Neriglissar's usurpation was the result of infighting between an older, wealthier and more influential branch of the royal family (represented by Nebuchadnezzar's daughters, Kashshaya in particular) and a less well established and younger, though more legitimate, branch (represented by Nebuchadnezzar's sons, such as Amel-Marduk).[22]

Titles

From one of his inscriptions, found on a pillar of one of Babylon's bridges, Amel-Marduk's titles read as follows:[24]

Amēl-Marduk, king of Babylon, the one who renovates Esagil and Ezida, son of Nebuchadnezzar, king of Babylon.[25]

Given that few inscriptions of Amel-Marduk are known, no more elaborate versions of his titulature are known.[26] He may also have used the title 'king of Sumer and Akkad', used by other Neo-Babylonian kings.[27]

See also

References

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 Weiershäuser & Novotny 2020, p. 1.

- ↑ Albertz 2018, p. 93.

- 1 2 Ayali-Darshan 2012, p. 29.

- ↑ Ayali-Darshan 2012, p. 26.

- 1 2 3 Ayali-Darshan 2012, p. 27.

- ↑ Popova 2015, p. 405.

- 1 2 3 Abraham 2012, p. 124.

- 1 2 Abraham 2012, p. 125.

- ↑ Ayali-Darshan 2012, pp. 27–28.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Ayali-Darshan 2012, p. 28.

- ↑ Sack 2004, p. 41.

- ↑ Parker & Dubberstein 1942, p. 10.

- ↑ Sack 1978, p. 129.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 Wiseman 1991, p. 241.

- ↑ Wiseman 1983, p. 12.

- ↑ Weisberg 1976, p. 67.

- ↑ Sack 2004, pp. 40–41.

- ↑ Lee 2021, p. 176.

- 1 2 Beaulieu 2018, p. 237.

- 1 2 Weiershäuser & Novotny 2020, p. 2.

- 1 2 3 Wiseman 1991, p. 242.

- 1 2 Beaulieu 1998, p. 200.

- ↑ Beaulieu 1998, p. 201.

- ↑ Weiershäuser & Novotny 2020, p. 29.

- ↑ Weiershäuser & Novotny 2020, p. 30.

- ↑ Weiershäuser & Novotny 2020, pp. 29–34.

- ↑ Da Riva 2013, p. 72.

Bibliography

- Abraham, Kathleen (2012). "A Unique Bilingual and Biliteral Artifact from the Time of Nebuchadnezzar II in the Moussaieff Private Collection". In Lubetski, Meir; Lubetski, Edith (eds.). New Inscriptions and Seals Relating to the Biblical World. Society of Biblical Literature. ISBN 978-1589835566.

- Albertz, Rainer (2018). "The Exilic Period as an Urgent Case for a Historical Reconstruction without the Biblical Text: the Neo-Babylonian Royal Inscriptions as a 'Primary Source'". In Grabbe, Lester L. (ed.). Even God Cannot Change the Past: Reflections on Seventeen Years of the European Seminar in Historical Methodology. Bloomsbury Publishing. ISBN 978-0567680563.

- Ayali-Darshan, Noga (2012). "A Redundancy in Nebuchadnezzar 15 and Its Literary Historical Significance". JANES. 32: 21–29.

- Beaulieu, Paul-Alain (1998). "Ba'u-asītu and Kaššaya, Daughters of Nebuchadnezzar II". Orientalia. 67 (2): 173–201. JSTOR 43076387.

- Beaulieu, Paul-Alain (2018). A History of Babylon, 2200 BC - AD 75. Wiley. ISBN 978-1405188999.

- Da Riva, Rocío (2013). The Inscriptions of Nabopolassar, Amel-Marduk and Neriglissar. Walter de Gruyter. ISBN 978-1614515876.

- Lee, Albert Sui Hung (2021). Dialogue on Monarchy in the Gideon-Abimelech Narrative: Ideological Reading in Light of Bakhtin's Dialogism. BRILL. ISBN 978-9004443853.

- Parker, Richard A.; Dubberstein, Waldo H. (1942). Babylonian Chronology 626 B.C. – A.D. 45 (PDF). The University of Chicago Press. OCLC 2600410.

- Popova, Olga (2015). "The Royal Family and its Territorial Implantation during the Neo-Babylonian Period". KASKAL. 12 (12): 401–410. doi:10.1400/239747.

- Sack, Ronald H. (1978). "Nergal-šarra-uṣur, King of Babylon as seen in the Cuneiform, Greek, Latin and Hebrew Sources". Zeitschrift für Assyriologie und Vorderasiatische Archäologie. 68 (1): 129–149. doi:10.1515/zava.1978.68.1.129. S2CID 161101482.

- Sack, Ronald H. (2004). Images of Nebuchadnezzar: The Emergence of a Legend (2nd Revised and Expanded ed.). Susquehanna University Press. ISBN 1-57591-079-9.

- Weiershäuser, Frauke; Novotny, Jamie (2020). The Royal Inscriptions of Amēl-Marduk (561–560 BC), Neriglissar (559–556 BC), and Nabonidus (555–539 BC), Kings of Babylon (PDF). Eisenbrauns. ISBN 978-1646021079.

- Weisberg, David B. (1976). "Review: Amēl-Marduk 562-560 B. C. A Study Based on Cuneiform, Old Testament, Greek, Latin and Rabbinical Sources By Ronald Herbert Sack". Journal of Near Eastern Studies. 35 (1): 67–69. doi:10.1086/372466.

- Wiseman, Donald J. (1983). Nebuchadrezzar and Babylon: The Schweich Letters. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0197261002.

- Wiseman, Donald J. (2003) [1991]. "Babylonia 605–539 B.C.". In Boardman, John; Edwards, I. E. S.; Hammond, N. G. L.; Sollberger, E.; Walker, C. B. F. (eds.). The Cambridge Ancient History: III Part 2: The Assyrian and Babylonian Empires and Other States of the Near East, from the Eighth to the Sixth Centuries B.C. (2nd ed.). Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-521-22717-8.