| Mithridates I 𐭌𐭄𐭓𐭃𐭕 | |

|---|---|

| King of Kings, Arsaces, Philhellene | |

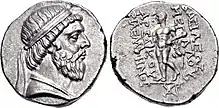

Mithridates I's portrait on the obverse of a tetradrachm, showing him wearing a beard and a royal Hellenistic diadem on his head | |

| King of the Parthian Empire | |

| Reign | 165–132 BC |

| Predecessor | Phraates I |

| Successor | Phraates II |

| Died | 132 BC |

| Spouse | Rinnu |

| Issue | Rhodogune Phraates II |

| Dynasty | Arsacid dynasty |

| Father | Priapatius |

| Religion | Zoroastrianism |

Mithridates I (also spelled Mithradates I or Mihrdad I; Parthian: 𐭌𐭄𐭓𐭃𐭕 Mihrdāt), also known as Mithridates I the Great,[1] was king of the Parthian Empire from 165 BC to 132 BC. During his reign, Parthia was transformed from a small kingdom into a major political power in the Ancient East as a result of his conquests.[2] He first conquered Aria, Margiana and western Bactria from the Greco-Bactrians sometime in 163–155 BC, and then waged war with the Seleucid Empire, conquering Media and Atropatene in 148/7 BC. In 141 BC, he conquered Babylonia and held an official investiture ceremony in Seleucia. The kingdoms of Elymais and Characene shortly afterwards became Parthian vassals. In c. 140 BC, while Mithridates was fighting the nomadic Saka in the east, the Seleucid king Demetrius II Nicator attempted to regain the lost territories; initially successful, he was defeated and captured in 138 BC, and shortly afterwards sent to one of Mithridates I's palaces in Hyrcania. Mithridates I then punished Elymais for aiding Demetrius, and made Persis a Parthian vassal.

Mithridates I was the first Parthian king to assume the ancient Achaemenid title of King of Kings. Due to his accomplishments, he has been compared to Cyrus the Great (r. 550–530 BC), the founder of the Achaemenid Empire.[3] Mithridates I died in 132 BC, and was succeeded by his son Phraates II.

Name

"Mithridates" is the Greek attestation of the Iranian name Mihrdāt, meaning "given by Mithra", the name of the ancient Iranian sun god.[4] The name itself is derived from Old Iranian Miθra-dāta-.[5] Mithra is a prominent figure in Zoroastrian sources, where he plays the role of the patron of khvarenah, i.e. kingly glory.[6] Mithra played an important role under the late Iranian Achaemenid Empire, and continued to grow throughout the Greek Seleucid period, where he was associated with the Greek gods Apollo or Helios, or the Babylonian god Nabu.[7] The role of Mithra peaked under the Parthians, which according to the modern historian Marek Jan Olbrycht, "seems to have been due to Zoroastrian struggles against the spread of foreign faiths in the Hellenistic period."[7]

Background

Mithridates was the son of Priapatius, the great-nephew of the first Arsacid king, Arsaces I (r. 247–217 BC). Mithridates had several brothers, including Artabanus and his older brother Phraates I, the latter succeeding their father in 176 BC as the Parthian king. According to Parthian custom, the reigning ruler had to be succeeded by his own son. However, Phraates I broke tradition and appointed his own brother Mithridates as his successor.[1] According to the 2nd-century Roman historian Justin, Phraates I had made his decision after noticing Mithridates' remarkable competence.[8]

Reign

The kingdom that Mithridates inherited in 165 BC was one of the many medium-sized powers that had risen with the decline of Seleucid Empire or had appeared on its borders.[9] Other kingdoms were Greco-Bactria, Cappadocia, Media Atropatene, and Armenia.[9] Mithridates I's domains encompassed present-day Khorasan Province, Hyrcania, northern Iran, and the southern part of present-day Turkmenistan.[9]

Wars in the east

He first turned his sights on the Greco-Bactrian Kingdom which had been considerably weakened as a result of its wars against the neighbouring Sogdians, Drangianans and Indians.[8] The new Greco-Bactrian king Eucratides I (r. 171–145 BC) had usurped the throne and was as a result met with opposition, such as the rebellion by the Arians, which was possibly supported by Mithridates I, as it would serve to his advantage.[10] Sometime between 163–155 BC, Mithridates I invaded the domains of Eucratides, whom he defeated and seized Aria, Margiana and western Bactria from.[11] Eucratides was supposedly made a Parthian vassal, as is indicated by the classical historians Justin and Strabo.[12] Merv became a stronghold of Parthian dominance in the northeast.[11] Some of Mithridates I's bronze coins portray an elephant on the reverse with the legend "of the Great King, Arsaces."[13] The Greco-Bactrians minted coins with images of elephants, which suggests that Mithridates I's coin mints of the very animal was possibly to celebrate his conquest of Bactria.[13]

Wars in the west

Turning his sights on the Seleucid realm, Mithridates I invaded Media and occupied Ecbatana in 148 or 147 BC; the region had recently become unstable after the Seleucids suppressed a rebellion led by Timarchus.[14] Mithridates I afterwards appointed his brother Bagasis as the governor of the area.[15] This victory was followed by the Parthian conquest of Media Atropatene.[16][17] In 141 BC, Mithridates I captured Babylonia in Mesopotamia, where he had coins minted at Seleucia and held an official investiture ceremony.[18] There Mithridates I appears to have introduced a parade of the New Year festival in Babylon, by which a statue of the ancient Mesopotamian god Marduk was led along parade way from the Esagila temple by holding the hands of the goddess Ishtar.[19] With Mesopotamia now in Parthian hands, the administrative focus of the empire relocated towards there instead of eastern Iran.[20] Mithridates I shortly afterwards retired to Hyrcania, whilst his forces subdued the kingdoms of Elymais and Characene and occupied Susa.[18] By this time, Parthian authority extended as far east as the Indus River.[21]

Whereas Hecatompylos had served as the first Parthian capital, Mithridates I established royal residences at Seleucia, Ecbatana, Ctesiphon and his newly founded city, Mithradatkert (Nisa), where the tombs of the Arsacid kings were built and maintained.[22] Ecbatana became the main summertime residence for the Arsacid royalty — the same city which had served as the capital of the Medes and as summer capital of the Achaemenid Empire.[23] Mithridates I may have made Ctesiphon the new capital of his enlarged empire.[24] The Seleucids were unable to retaliate immediately as general Diodotus Tryphon led a rebellion at the capital Antioch in 142 BC.[25] However, an opportunity for counter-invasion arose for the Seleucids in c. 140 BC when Mithridates I was forced to leave for the east to contain an invasion by the Saka.[24]

The Seleucid ruler Demetrius II Nicator was at first successful in his efforts to reconquer Babylonia, however, the Seleucids were eventually defeated and Demetrius himself was captured by Parthian forces in 138 BC.[26] He was afterwards paraded in front of the Greeks of Media and Mesopotamia with the intention of making them to accept Parthian rule.[27] Afterwards, Mithridates I had Demetrius sent to one of his palaces in Hyrcania. There Mithridates I treated his captive with great hospitality; he even married his daughter Rhodogune to Demetrius.[28] According to Justin, Mithridates I had plans for Syria, and planned to use Demetrius as his instrument against the new Seleucid ruler Antiochus VII Sidetes (r. 138–129 BC).[29] His marriage to Rhodogune was in reality an attempt by Mithridates I to incorporate the Seleucid lands into the expanding Parthian realm.[29] Mithridates I then punished the Parthian vassal kingdom of Elymais for aiding the Seleucids–he invaded the region once more and captured two of their major cities.[30][24]

Around the same period, Mithridates I conquered the southwestern Iranian region of Persis and installed Wadfradad II as its frataraka; he granted him more autonomy, most likely in an effort to maintain healthy relations with Persis as the Parthian Empire was under constant conflict with the Saka, Seleucids, and the Mesenians.[31][32] He was seemingly the first Parthian monarch to have an influence on the affairs of Persis. The coinage of Wadfradad II shows influence from the coins minted under Mithridates I.[33] Mithridates I died in c. 132 BC, and was succeeded by his son Phraates II.[34]

Coinage and Imperial ideology

Since the early 2nd century BC, the Arsacids had begun adding obvious signals in their dynastic ideology, which emphasized their association with the heritage of the ancient Achaemenid Empire. Examples of these signs included a fictitious claim that the first Arsacid king, Arsaces I (r. 247–217 BC) was a descendant of the Achaemenid King of Kings, Artaxerxes II (r. 404–358 BC).[35] Achaemenid titles were also assumed by the Arsacids; Mithridates I was the first Arsacid ruler who adopted the former Achaemenid title of "King of Kings". Though Mithridates I was the first to readopt the title, it was not commonly used among Parthian rulers until the reign of his nephew and namesake Mithridates II, from c. 109/8 BC onwards.[35][24]

The Arsacid monarchs preceding Mithridates I are depicted on the obverse of their coins with a soft cap, known as the bashlyk, which had also been worn by Achaemenid satraps.[35] On the reverse, there is a seated archer, dressed in an Iranian riding costume.[36][37] The earliest coins of Mithridates I show him wearing the soft cap as well, however coins from the later part of his reign show him for the first time wearing the royal Hellenistic diadem.[38][39] He thus embraces the image of a Hellenistic monarch, yet chooses to appear bearded in the traditional Iranian custom.[39] Mithridates I also titled himself Philhellene ("friend of the Greeks") on his coins, which was a political act done in order to establish friendly relations with his newly conquered Greek subjects and cooperate with its elite.[40][41] On the reverse of his new coins, the Greek divine hero Heracles is depicted, holding a club in his left hand and a cup in his right hand.[42] In the Parthian era, Iranians used Hellenistic iconography to portray their divine figures, thus Heracles was seen as a representation of the Avestan Verethragna.[43]

The other titles that Mithridates I used in his coinage was "of Arsaces", which was later changed into "of King Arsaces", and eventually, "of the Great King Arsaces."[39] The name of the first Arsacid ruler Arsaces I had become a royal honorific among the Arsacid monarchs out of admiration for his achievements.[1][44] Another title used in Mithridates' coinage was "whose father is a god", which was also later used by his son, Phraates II.[39]

Building activities

Under Mithridates I, the city of Nisa, which served as a royal residence of the Arsacids,[45] was completely transformed.[46] Renamed Mithradatkert ("Mithridates' fortress"), the city was made into a religious hub that was dedicated to promote the worship of Arsacid family.[46] A sculpted head broken off from a larger statue from Mithradatkert, depicting a bearded man with noticeably Iranian facial characteristics, may be a portrait of Mithridates I.[47][39] Ctesiphon, a city on the Tigris next to Seleucia, was founded during his reign.[48] According to Strabo, the city was established as a camp for the Parthian troops, due to Arsacids not finding it suitable to send them into Seleucia.[48] Pliny the Elder, however, states that Ctesiphon was founded in order to lure the inhabitants of Seleucia out of their city.[48]

The Xong-e Noruzi relief

One of the most famous Parthian reliefs is a scene with six men at Xong-e Noruzi in Khuzestan.[49] In the middle of the figure, the main character is in frontal view in Parthian costume. To the right are three other men, though slightly smaller carved into the stone. On the left is a rider on a horse. The figure is shown in profile. Behind the rider is followed by another man, again in profile. The stylistic difference between the Hellenistic style portrayed in more riders and reproduced in the Parthian style in other characters led to the assumption that the four men were later carved into the rock on the right side. The rider probably represents a king, and has been identified as Mithridates I, who conquered Elymais in 140/139 BC. Accordingly, the relief is celebrating his victory. This interpretation was originally accepted by many scholars.[50] However, more recently this view has been challenged and other theories have been proposed, including one that the rider is a local ruler of the Elymais.[51][52] The modern historian Trudy S. Kawami has suggested the figure might be Kamnaskires II Nikephoros, the second ruler of Elymais, who declared independence from the Seleucids.[53]

Legacy

Of all Mithridates' accomplishments, his greatest one was to transform Parthia from a small kingdom into a major political power in the Ancient East.[24] His conquests in the west seem to have been based on a plan to reach Syria and, thereby, gain Parthian access to the Mediterranean Sea.[24] The modern historian Klaus Schippmann emphasises this, stating "Certainly, the exploits of Mithridates I can no longer simply be classified as a series of raids for the purpose of pillaging and capturing booty."[24] The Iranologist Homa Katouzian has compared Mithridates I to Cyrus the Great (r. 550–530 BC), the founder of the Achaemenid Empire.[3]

References

- 1 2 3 Dąbrowa 2012, p. 169.

- ↑ Frye 1984, p. 211.

- 1 2 Katouzian 2009, p. 41.

- ↑ Mayor 2009, p. 1.

- ↑ Schmitt 2005.

- ↑ Olbrycht 2016, pp. 97, 99–100.

- 1 2 Olbrycht 2016, p. 100.

- 1 2 Justin, xli. 41.

- 1 2 3 Olbrycht 2010, pp. 229–230.

- ↑ Olbrycht 2010, p. 234.

- 1 2 Olbrycht 2010, p. 237.

- ↑ Olbrycht 2010, pp. 236–237.

- 1 2 Dąbrowa 2016, p. 40.

- ↑ Curtis 2007, pp. 10–11; Bivar 1983, p. 33; Garthwaite 2005, p. 76

- ↑ Shayegan 2011, pp. 72–74.

- ↑ Olbrycht 2010, pp. 239–240.

- ↑ Dąbrowa 2010, p. 28.

- 1 2 Curtis 2007, pp. 10–11; Brosius 2006, pp. 86–87; Bivar 1983, p. 34; Garthwaite 2005, p. 76;

- ↑ Shayegan 2011, p. 67.

- ↑ Canepa 2018, p. 70.

- ↑ Garthwaite 2005, p. 76; Bivar 1983, p. 35

- ↑ Brosius 2006, pp. 103, 110–113

- ↑ Kennedy 1996, p. 73; Garthwaite 2005, p. 77; Brown 1997, pp. 80–84

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 Schippmann 1986, pp. 525–536.

- ↑ Bivar 1983, p. 34

- ↑ Brosius 2006, p. 89; Bivar 1983, p. 35; Shayegan 2007, pp. 83–103, 178

- ↑ Dąbrowa 2018, p. 75.

- ↑ Brosius 2006, p. 89; Bivar 1983, p. 35; Shayegan 2007, pp. 83–103; Dąbrowa 2018, p. 75

- 1 2 Nabel 2017, p. 32.

- ↑ Hansman 1998, pp. 373–376.

- ↑ Wiesehöfer 2000, p. 195.

- ↑ Shayegan 2011, p. 178.

- ↑ Sellwood 1983, p. 304.

- ↑ Assar 2009, p. 134.

- 1 2 3 Dąbrowa 2012, p. 179.

- ↑ Sinisi 2012, p. 280.

- ↑ Curtis 2012, p. 68.

- ↑ Brosius 2006, pp. 101–102.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Curtis 2007, p. 9.

- ↑ Dąbrowa 2012, p. 170.

- ↑ Dąbrowa 2013, p. 54.

- ↑ Curtis 2012, p. 69.

- ↑ Curtis 2012, pp. 69, 76–77.

- ↑ Kia 2016, p. 23.

- ↑ Dąbrowa 2012, p. 179–180.

- 1 2 Dąbrowa 2010, pp. 42–43.

- ↑ Invernizzi.

- 1 2 3 Kröger 1993, pp. 446–448.

- ↑ Mathiesen 1992, pp. 119–121.

- ↑ Shayegan 2011, p. 106.

- ↑ Colledge 1977, p. 92.

- ↑ Shayegan 2011, pp. 106–107.

- ↑ Kawami 2013, pp. 762–763.

Bibliography

Ancient works

- Strabo, Geographica.

- Justin, Epitome of the Philippic History of Pompeius Trogus.

Modern works

- Assar, Gholamreza F. (2009). "Artabanus of Trogus Pompeius' 41st Prologue". Electrum. Kraków. 15.

- Brown, Stuart C. (1997). "Ecbatana". Encyclopaedia Iranica, Vol. VIII, Fasc. 1. pp. 80–84.

- Bickerman, Elias J. (1983). "The Seleucid Period". In Yarshater, Ehsan (ed.). The Cambridge History of Iran, Volume 3(1): The Seleucid, Parthian and Sasanian Periods. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. pp. 3–20. ISBN 0-521-20092-X.

- Bivar, A.D.H. (1983). "The Political History of Iran under the Arsacids". In Yarshater, Ehsan (ed.). The Cambridge History of Iran, Volume 3(1): The Seleucid, Parthian and Sasanian Periods. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. pp. 21–99. ISBN 0-521-20092-X.

- Brosius, Maria (2006), The Persians: An Introduction, London & New York: Routledge, ISBN 0-415-32089-5

- Canepa, Matthew P. (2018). "The Rise of the Arsacids and a New Iranian Topography of Power". The Iranian Expanse: Transforming Royal Identity through Architecture, Landscape, and the Built Environment, 550 BCE–642 CE. University of California Press. pp. 1–512. ISBN 9780520964365.

- Curtis, Vesta Sarkhosh; Stewart, Sarah, eds. (2007), The Age of the Parthians, Ideas of Iran, vol. 2, London: I. B. Tauris

- Curtis, Vesta Sarkhosh (2007), "The Iranian Revival in the Parthian Period", in Curtis, Vesta Sarkhosh and Sarah Stewart (ed.), The Age of the Parthians: The Ideas of Iran, vol. 2, London & New York: I.B. Tauris & Co Ltd., in association with the London Middle East Institute at SOAS and the British Museum, pp. 7–25, ISBN 978-1-84511-406-0

- Curtis, Vesta Sarkhosh (2012). "Parthian coins: Kingship and Divine Glory". The Parthian Empire and its Religions. pp. 67–83. ISBN 9783940598134.

- Colledge, Malcolm A. R. (1977). Parthian art. Elek. pp. 1–200. ISBN 9780236400850.

- Dąbrowa, Edward (2009). "Mithradates I and the Beginning of the Ruler-cult in Parthia". Electrum. 15: 41–51.

- Dąbrowa, Edward; et al. (2010). "The Arsacids and their State". In Rollinger, R. (ed.). Altertum und Gegenwart. 125 Jahre Alte Geschichte in Innsbruck. Vortraege der Ringvorlesung Innsbruck 2010. Vol. XI. pp. 21–52.

- Dąbrowa, Edward (2013). "The Parthian Aristocracy: its Social Position and Political Activity". Parthica. 15: 53–62.

- Dąbrowa, Edward (2018). "Arsacid Dynastic Marriages". Electrum. 25: 73–83. doi:10.4467/20800909EL.18.005.8925.

- Dąbrowa, Edward (2012). "The Arsacid Empire". In Daryaee, Touraj (ed.). The Oxford Handbook of Iranian History. Oxford University Press. pp. 164–186. ISBN 978-0-19-987575-7. Archived from the original on 2019-01-01. Retrieved 2019-02-03.

- Daryaee, Touraj (2016). "From Terror to Tactical Usage: Elephants in the Partho-Sasanian Period". In Curtis, Vesta Sarkhosh; Pendleton, Elizabeth J.; Alram, Michael; Daryaee, Touraj (eds.). The Parthian and Early Sasanian Empires: Adaptation and Expansion. Oxbow Books. ISBN 9781785702082.

- Frye, Richard Nelson (1984). The History of Ancient Iran. C.H.Beck. pp. 1–411. ISBN 9783406093975.

false.

- Garthwaite, Gene Ralph (2005), The Persians, Oxford & Carlton: Blackwell Publishing, Ltd., ISBN 1-55786-860-3

- Invernizzi, Antonio. "Nisa". Encyclopaedia Iranica.

- Katouzian, Homa (2009), The Persians: Ancient, Medieval, and Modern Iran, New Haven & London: Yale University Press, ISBN 978-0-300-12118-6

- Kawami, Trudy S. (2013). "Parthian and Elymaean Rock Reliefs". In Potts, Daniel T. (ed.). The Oxford Handbook of Ancient Iran. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0199733309.

- Kröger, Jens (1993). "Ctesiphon". Encyclopaedia Iranica, Vol. IV, Fasc. 4. pp. 446–448.

- Kennedy, David (1996), "Parthia and Rome: eastern perspectives", in Kennedy, David L.; Braund, David (eds.), The Roman Army in the East, Ann Arbor: Cushing Malloy Inc., Journal of Roman Archaeology: Supplementary Series Number Eighteen, pp. 67–90, ISBN 1-887829-18-0

- Hansman, John F. (1998). "Elymais". Encyclopaedia Iranica, Vol. VIII, Fasc. 4. pp. 373–376.

- Kia, Mehrdad (2016). The Persian Empire: A Historical Encyclopedia [2 volumes]: A Historical Encyclopedia. ABC-CLIO. ISBN 978-1610693912.

- Mathiesen, Hans Erik (1992). Sculpture in the Parthian Empire. Aarhus University Press. pp. 1–231. ISBN 9788772883113.

- Mayor, Adrienne (2009). The Poison King: The Life and Legend of Mithradates, Rome's Deadliest Enemy. Princeton University Press. pp. 1–448. ISBN 9780691150260.

- Nabel, Jake (2017). "The Seleucids Imprisoned: Arsacid-Roman Hostage Submission and Its Hellenistic Precedents": 25–50.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - Olbrycht, Marek Jan (2010). "Mithradates I of Parthia and His Conquests up to 141 B.C.": 229–245.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - Olbrycht, Marek Jan (2016). "The Sacral Kingship of the early Arsacids I. Fire Cult and Kingly Glory": 91–106.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - Pourshariati, Parvaneh (2008). Decline and Fall of the Sasanian Empire: The Sasanian-Parthian Confederacy and the Arab Conquest of Iran. London and New York: I.B. Tauris. ISBN 978-1-84511-645-3.

- Roller, Duane. 2020. Empire of the Black Sea: The Rise and Fall of the Mithridatic World. Oxford University Press.

- Schippmann, K. (1986). "Arsacids ii. The Arsacid dynasty". Encyclopaedia Iranica, Vol. II, Fasc. 5. pp. 525–536.

- Schmitt, Rüdiger (2005). "Personal Names, Iranian iv. Parthian Period". Encyclopaedia Iranica.

- Sellwood, David (1983). "Minor States in Southern Iran". In Yarshater, Ehsan (ed.). The Cambridge History of Iran, Volume 3(1): The Seleucid, Parthian and Sasanian Periods. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. pp. 299–322. ISBN 0-521-20092-X.

- Shayegan, Rahim M. (2007), "On Demetrius II Nicator's Arsacid Captivity and Second Rule", Bulletin of the Asia Institute, 17: 83–103

- Shayegan, M. Rahim (2011). Arsacids and Sasanians: Political Ideology in Post-Hellenistic and Late Antique Persia. Cambridge University Press. pp. 1–539. ISBN 9780521766418.

- Sinisi, Fabrizio (2012). "The Coinage of the Parthians". In Metcalf, William E. (ed.). The Oxford Handbook of Greek and Roman Coinage. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0195305746.

- Wiesehöfer, Josef (2000). "Frataraka". Encyclopaedia Iranica, Vol. X, Fasc. 2. p. 195.