| Bad Axe Massacre | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the Black Hawk War | |||||||

_(14590318379).jpg.webp) The American steamboat, Warrior at the Battle of Bad Axe attacking fleeing Sauk and Fox Indians trying to escape across the Mississippi River which resulted in a massacre in the last major engagement of the Black Hawk War | |||||||

| |||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

| Sauk and Fox affiliated with the British Band | Dakota Sioux | ||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

| Black Hawk (Not present on second day) | Wapasha II | ||||||

| Strength | |||||||

| appx. 500 (including non-combatants) | appx. 1,300 | ||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||

|

at least 150 KIA (including non-combatants) 75 captured | 5 KIA, 19 WIA | ||||||

Location within Wisconsin  Battle of Bad Axe (the United States) | |||||||

The Bad Axe Massacre was a massacre of Sauk (Sac) and Fox Indians by United States Army regulars and militia that occurred on August 1–2, 1832. This final scene of the Black Hawk War took place near present-day Victory, Wisconsin, in the United States. It marked the end of the war between white settlers and militia in Illinois and Michigan Territory, and the Sauk and Fox tribes under warrior Black Hawk.

The massacre occurred in the aftermath of the Battle of Wisconsin Heights, as Black Hawk's band fled the pursuing militia. The militia caught up with them on the eastern bank of the Mississippi River, a few miles downstream from the mouth of the Bad Axe River. Historians have called it a massacre since the 1850s. The fighting took place over two days, with the steamboat Warrior present on both days. By the second day, Black Hawk and most of the Native American leaders had fled, though many of the band stayed behind. The victory for the United States was brutal and decisive and the end of the war allowed much of Illinois and present-day Wisconsin to be opened for further settlement.

Background

In an 1804 treaty between the governor of Indiana Territory and a council of leaders from the Sauk and Fox, Native American tribes ceded 50 million acres (200,000 km2) of their land to the United States for $2,234.50 and an annual annuity of $1,000.[2][3] The treaty also allowed the Sauk and Fox to remain on their land until it was sold.[3] The treaty was controversial; Sauk war leader Black Hawk, and others disputed its validity because they said that the full tribal councils were not consulted and the council that negotiated the treaty did not have the authority to cede land.[2] After the discovery of lead in and around Galena, Illinois, during the 1820s, miners began moving into the area ceded in the 1804 treaty. When the Sauk and Fox returned from the winter hunt in 1829, they found their land occupied by white settlers and were forced to return west of the Mississippi River.[3]

Angered by the loss of his birthplace, Black Hawk led a number of incursions across the Mississippi River into Illinois between 1830 and 1831, but each time was persuaded to return west without bloodshed. In April 1832, encouraged by promises of alliance with other tribes and the British, he again moved his so-called "British Band" of around 1,000 warriors and non-combatants into Illinois.[2] Finding no allies, he attempted to return across the Mississippi to present-day Iowa, but the undisciplined Illinois Militia's actions led to Black Hawk's surprising victory at the Battle of Stillman's Run.[4] A number of other engagements followed, and the militia of Michigan Territory and the state of Illinois were mobilized to hunt down Black Hawk's band. The conflict became known as the Black Hawk War.

The period between the Battle of Stillman's Run in May and the raid at Sinsinawa Mound in late June was filled with war-related activity. A series of attacks at Buffalo Grove, the Plum River settlement, Fort Blue Mounds, and the war's most famous incident, the Indian Creek massacre, all took place between mid-May and late June 1832.[5] Two key battles, one at Horseshoe Bend on June 16 and the other at Waddams Grove on June 18, played a role in changing public perception about the militia after its defeat at Stillman's Run.[6][7][8] The Battle of Apple River Fort on June 24 marked the end of a week that was an important turning point for the settlers. The fight was a 45-minute gun battle between defenders garrisoned inside Apple River Fort and Sauk and Fox warriors led by Chief Black Hawk.[9]

The next day, after an inconclusive skirmish at Kellogg's Grove, Black Hawk and his band fled the approaching militia through modern-day Wisconsin. The Sinsinawa Mound raid occurred on June 29, five days after the Battle of Apple River Fort. As the band fled the pursuing militia, they passed through what are now Beloit and Janesville, then followed the Rock River toward Horicon Marsh, where they headed west toward the Four Lakes region, near modern-day Madison.[10] On July 21, 1832, the militia caught up with Black Hawk's band as they attempted to cross the Wisconsin River, near the present-day Town of Roxbury, in Dane County, Wisconsin, resulting in the Battle of Wisconsin Heights.[2][11]

Prelude

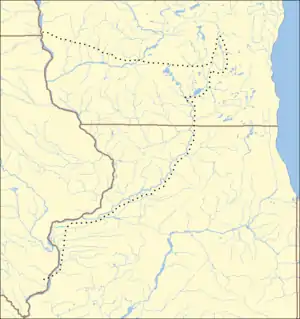

Michigan Territory (Wisconsin)

Illinois

Unorganized

Territory (Iowa)  |

| Map of Black Hawk War sites Symbols are wikilinked to article |

A few hours after midnight on July 22, with Black Hawk's band resting on a knoll on the Wisconsin Heights Battlefield, Neapope, one of the key leaders accompanying Black Hawk, attempted to explain to the nearby militia officers that his group wanted only to end the fighting and go back across the Mississippi River.[12][13] In a "loud shrill voice" he delivered a conciliatory speech in his native Ho-Chunk language, assuming Pauquette and his band of Ho-Chunk guides were still with the militia at Wisconsin Heights.[13] However, the U.S. troops did not understand him, because their Sauk allies had already departed the battlefield.[12] Following this failed attempt at peace, Neapope abandoned the cause and returned to a nearby Ho-Chunk village. The British Band had slowly disintegrated over the months of conflict; most of the Ho-Chunk and Potawatomi that had joined were gone by the Battle of Bad Axe. Others, especially children and the elderly, had died of starvation while the band fled the pursuing militia through the swamps around Lake Koshkonong.[2]

Following the engagement at Wisconsin Heights, the militia decided to wait until the following day to pursue Black Hawk. They heard, but did not understand, Neapope's speech during the night, and to their surprise, when morning arrived their enemy had disappeared.[7][10] The battle, though militarily devastating for the British Band, had allowed much of the group to escape to temporary safety across the Wisconsin River. The reprieve was short-lived for many – a group of Fox women and children who attempted to escape down the Wisconsin following the battle were captured by U.S.-allied tribes or shot by soldiers further downstream.[2] During the night, while the non-combatants escaped in canoes, Black Hawk and the remaining warriors crossed the river near present-day Prairie du Sac, Wisconsin.[11] The band fled west over rugged terrain toward the banks of the Mississippi River, with a week's head start on the militia.

While the band fled west, Commanding General Henry Atkinson trimmed his force to a few hundred men and set out to join militia commanders Henry Dodge and James D. Henry to regroup and resupply at Fort Blue Mounds.[2][10] Under the command of Atkinson, around 1,300 men from the commands of Henry, Dodge, Alexander Posey and Milton Alexander crossed the Wisconsin River between July 27–28 near present day Helena, Wisconsin.[2] The well-fed and rested militia force picked up Black Hawk's trail again on July 28 near present-day Spring Green, Wisconsin, and relatively quickly closed the gap on the famished and battle-weary band of Native Americans.[2][10] On August 1, Black Hawk and about 500 men, women, and children arrived at the eastern bank of the Mississippi, a few miles downstream from the mouth of the Bad Axe River. On arrival, the leaders of the band, including Black Hawk, called a council meeting to discuss their next move.[2]

Battle

First day

Near the mouth of the Bad Axe River, on August 1, 1832, Black Hawk and Winnebago prophet and fellow British Band leader White Cloud advised the band against wasting time building rafts to cross the Mississippi River, because the U.S. forces were closing in, urging them instead to flee northward and seek refuge among the Ho-Chunk. However, most of the band chose to try to cross the river.[2]

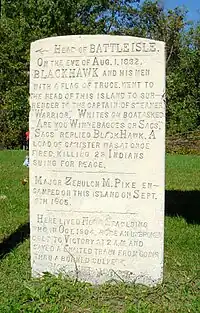

While some of the band managed to escape across the Mississippi River that afternoon, the steamboat Warrior, commanded by Captain Joseph Throckmorton, appeared on the scene and halted the band's attempt to cross to safety.[14] Waving a white flag, Black Hawk tried to surrender, but as had happened in the past the soldiers failed to understand and the scene deteriorated into battle.[2] The warriors who survived the initial volley found cover and returned fire and a two-hour firefight ensued. The Warrior eventually withdrew from battle because of lack of fuel, and returned to Fort Crawford at Prairie du Chien, Wisconsin.

At the time, newspaper reports stated that 23 Native Americans were killed, including one woman estimated to be 19 years old; she was shot through her child's upper arm as she stood holding the child watching the battle. Her child was retrieved by Lieutenant Anderson after the battle, and taken to the surgical tent, where the baby's arm was amputated. The child was then taken to Prairie du Chien, where he is believed to have recovered.[15] The fight convinced Black Hawk that refuge lay to the north, not west across the Mississippi. In one of his last actions as commander of the British Band, Black Hawk implored his followers to flee with him, to the north. Many did not listen, and late on August 1, Black Hawk, White Cloud and about three dozen other followers left the British Band and fled northward. Most of the remaining warriors and non-combatants remained on the eastern bank of the Mississippi.[2] Forces on the Warrior suffered only one casualty – a retired soldier from Fort Snelling was wounded in the knee during the fight.[16]

Second day

At 2 a.m. on August 2, Atkinson's forces awoke and began to break camp, setting out before sunrise. They had moved only a few miles when they ran into the rear scout element of the remaining Sauk and Fox forces. The Sauk scouts attempted to lead the enemy away from the main camp and were initially successful.[2] The combined U.S. forces fell into formation for battle: Generals Alexander and Posey formed the right wing, Henry the left wing, and Dodge and the regulars the center element. As the Native Americans retreated toward the river, the militia's left wing were left in the rear without orders.[17] When a regiment stumbled across the main trail to the camp, the scouts could only fight in retreat and hope that they had given their comrades a chance to escape the militia, while the Sauk and Fox kept retreating to the river.[17] However, Warrior returned after obtaining more wood in Prairie du Chien, leaving the refueling point about midnight and arriving at Bad Axe about 10 a.m.[2][18] The slaughter that followed continued for the next eight hours.[2]

Henry's men, the entire left wing, descended a bluff into the midst of several hundred Sauk and Fox warriors, and a desperate bayonet and musket battle followed. Women and children fled the fight into the river, where many drowned immediately. The battle continued for 30 minutes before Atkinson came up with Dodge's center element, cutting off escape for many of the remaining Native warriors. Some warriors managed to escape the fight to a willow island, which was being peppered with canister shot and gunfire by Warrior.[17]

The soldiers killed everyone who tried to run for cover or cross the river; men, women and children alike were shot dead. More than 150 people were killed outright at the scene of the battle, which many combatants later termed a massacre. The soldiers then scalped most of the dead, and cut long strips of flesh from others for use as razor strops. U.S. forces captured an additional 75 Native Americans. Of the total 400–500 Sauk and Fox at Bad Axe on August 2, most were killed at the scene, others escaped across the river. Those who escaped across the river found only temporary reprieve as many were captured and killed by Sioux warriors acting in support of the U.S. Army. Sioux brought 68 scalps and 22 prisoners to the U.S. Indian agent Joseph M. Street in the weeks following the battle. The United States suffered five killed in action and 19 wounded.[2]

Context

On August 3, 1832, the day after the battle, Indian Agent Street wrote to William Clark describing the scene at Bad Axe and the events that occurred there. He stated that most of the Sauk and Fox were shot in the water or drowned trying to cross the Mississippi to safety.[19] Major John Allen Wakefield published an account of the war in 1834, which included a description of the battle. His description characterized the killing of women and children as a mistake:[20]

During the engagement we killed some of the squaws through mistake. It was a great misfortune to those miserable squaws and children, that they did not carry into execution [the plan] they had formed on the morning of the battle -- that was, to come and meet us, and surrender themselves prisoners of war. It was a horrid sight to witness little children, wounded and suffering the most excruciating pain, although they were of the savage enemy, and the common enemy of the country."[20]

Black Hawk's own account, though he was not present at the battle's second day, termed the incident a massacre.[21] Later histories continued to assail the actions of the whites at Bad Axe. The 1887 Perry A. Armstrong book, The Sauks and the Black Hawk War, called Throckmorton's actions "inhuman and dastardly" and went on to call him a "second Nero or Calligula [sic]".[22] In 1898, during events honoring the 66th anniversary of the battle, Reuben Gold Thwaites termed the fight a "massacre" during a speech at the battle site.[16] He emphasized this theme again in a 1903 collection of essays.[17]

Modern-day historians have continued to characterize the battle as a wholesale massacre. Mark Grimsley, a history professor at Ohio State University, concluded in 2005, based on other modern accounts, that the Battle of Bad Axe would be better termed a massacre.[2][19] Kerry A. Trask's 2007 work, Black Hawk: The Battle for the Heart of America, points to the writings of Wakefield as evidence that delusional beliefs about doing brave deeds and magnifying manliness spurred the U.S. forces to revel in and pursue massacring and exterminating the Sauk and Fox.[16] Trask concluded that Wakefield's statement "I must confess, that it filled my heart with gratitude and joy, to think that I had been instrumental, with many others, in delivering my country of those merciless savages, and restoring those people again to their peaceful homes and firesides," was a viewpoint held by nearly all militia members.[16][20]

Aftermath

The Black Hawk War of 1832 resulted in the deaths of at least 70 settlers and soldiers, and hundreds of Black Hawk's band.[2][23] As well as the combat casualties of the war, a relief force under General Winfield Scott suffered hundreds deserted and dead, many from cholera.[24] The end of the war at Bad Axe ended the large-scale threat of Native American attacks in northwest Illinois, and allowed further settlement of Illinois and what became Iowa and Wisconsin.[25]

The members of the British Band, and the Fox, Kickapoo, Sauk, Ho-Chunk and Potawatomi that later joined them, suffered unknown numbers of dead during the war.[23] While some died fighting, others were tracked down and killed by Sioux, Menominee, Ho-Chunk, and other native tribes. Still others died of starvation or drowned during the Band's long trek up the Rock River toward the mouth of the Bad Axe.[23] The entire British Band was not wiped out at Bad Axe; some survivors drifted back home to their villages. This was relatively simple for the Potawatomi and Ho-Chunk of the band.[23] Many Sauk and Fox found return to their homes more difficult, and while some returned safely, others were held in custody by the army. Prisoners, some taken at the Battle of Bad Axe, and others taken by U.S.-aligned Native American tribes in the following weeks, were taken to Fort Armstrong at modern Rock Island, Illinois.[23] About 120 prisoners – men, women, and children – waited until the end of August to be released by General Winfield Scott.[23]

Black Hawk and most of the leaders of the British Band were not immediately captured following the conclusion of hostilities. On August 20, Sauk and Fox under Keokuk turned over Neapope and several other British Band chiefs to Winfield Scott at Fort Armstrong. Black Hawk, however, remained elusive. After fleeing the battle scene with White Cloud and a small group of warriors, Black Hawk had moved northeast toward the headwaters of the La Crosse River. The group camped for a few days and was eventually counseled by a group of Ho-Chunk, which included White Cloud's brother, to surrender. Though they initially resisted the pleas for surrender, the group eventually traveled to the Ho-Chunk village at La Crosse and prepared to surrender. On August 27, 1832, Black Hawk, White Cloud and the remnants of the British Band surrendered to Joseph M. Street at Prairie du Chien.[2]

Notes

- ↑ "Archived copy" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 2018-09-20. Retrieved 2019-05-18.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link) - 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 Lewis, James. "The Black Hawk War of 1832 Archived August 15, 2009, at the Wayback Machine", Abraham Lincoln Digitization Project, Northern Illinois University, p. 2C. Retrieved 1 August 2007.

- 1 2 3 "Apple River Fort Archived 2007-09-05 at the Wayback Machine", Historic Sites, Illinois Historic Preservation Agency. Retrieved 12 September 2008.

- ↑ "14 May: Black Hawk's Victory at the Battle of Stillman's Run", Historic Diaries: The Black Hawk War, Wisconsin State Historical Society. Retrieved 6 August 2007.

- ↑ "21 May, Indian Creek, Ill.: Abduction of the Hall Sisters", Historic Diaries: The Black Hawk War, Wisconsin State Historical Society. Retrieved 21 September 2007.

- ↑ "James Stephenson Describes the Battle at Yellow Creek Archived 2007-09-29 at the Wayback Machine", Historic Diaries: The Black Hawk War, Wisconsin Historical Society. Retrieved 21 September 2007.

- 1 2 "16 June: Henry Dodge Describes The Battle of the Pecatonica Archived 2007-09-29 at the Wayback Machine", Historic Diaries: The Black Hawk War, Wisconsin State Historical Society. Retrieved 21 September 2007.

- ↑ "16 June: Peter Parkinson Recalls the Battle of the Pecatonica", Historic Diaries: The Black Hawk War, Wisconsin State Historical Society. Retrieved 21 September 2007.

- ↑ Harmet, A. Richard. "Apple River Fort Site Archived October 31, 2007, at the Wayback Machine", (PDF), National Register of Historic Places Nomination Form, 31 March 1997, HAARGIS Database, Illinois Historic Preservation Agency. Retrieved 27 September 2007.

- 1 2 3 4 McCann, Dennis. "Black Hawk's name, country's shame lives on", Milwaukee Journal-Sentinel, 28 April 2007. Retrieved 30 July 2007.

- 1 2 Cole, Harry Ellsworth, ed. A Standard History of Sauk County, Wisconsin: Volume I, Chicago: Lewis Publishing Co., 1918, pp. 170-171. Available online via The State of Wisconsin Collection, University of Wisconsin. Retrieved 2 August 2007.

- 1 2 Campbell, Henry Colin. Wisconsin in Three Centuries, 1634-1905, (Google Books), The Century History Company: 1906, pp. 199-202. Retrieved 2 August 2007.

- 1 2 "The Battle of Wisconsin Heights," Highlights: Archives, Wisconsin State Historical Society. Retrieved 8 August 2007.

- ↑ Petersen, William John. Steamboating on the Upper Mississippi, (Google Books), Courier Dover Publications: 1996, pp. 176–77, (ISBN 0-486-28844-7). Retrieved 22 October 2007.

- ↑ Niles' Register, Misc. "Scene at the Battle of the Bad Axe," 3 November 1832.

- 1 2 3 4 Trask, Kerry A. Black Hawk: The Battle for the Heart of America, (Google Books), Henry Holt and Co., New York City: 2007, pp. 279, and 290–93. Retrieved 22 October 2007.

- 1 2 3 4 Thwaites, Rueben Gold. How George Rogers Clark Won the Northwest: And Other Essays in Western History, (Google Books), A.C. McClurg & Co., Chicago: 1903, pp. 186–92. Retrieved 22 October 2007.

- ↑ Smith, William Rudolph. The History of Wisconsin: In Three Parts, Historical, Documentary, and (Google Books), Part II: Documentary, Vol. III, B. Brown, Madison, Wisconsin: 1854 pp. 229–30. Retrieved 22 October 2007.

- 1 2 Grimsley, Mark. "Interrogating the Project of Military History Archived August 14, 2009, at the Wayback Machine, War Historian, Ohio State University. Retrieved 22 October 2007.

- 1 2 3 Wakefield, John Allen; Stevens, Frank Everett, ed. History of the War between the United States and the Sac and Fox Nations of Indians, and Parts of Other Disaffected Tribes of Indians, in the Years Eighteen Hundred and Twenty-Seven, Thirty-One, and Thirty-Two; Reprinted as: Wakefield's History of the Black Hawk War, Original Publication: Jacksonville, Ill.: Calvin Goudy, 1834. Reprint Publication: Chicago: The Caxton Club, 1908, Chapter 7: Section 133, and Chapter 8: Section 144. Retrieved 22 October 2007.

- ↑ Black Hawk. "The Massacre at Bad Axe: Black Hawk's Account," via the Wisconsin Historical Society. Retrieved 22 October 2007.

- ↑ Armstrong, Perry A. The Sauks and the Black Hawk War (Google Books), H.W. Rokker: 1887, pp. 467–69. Retrieved 22 October 2007.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Lewis, James. "The Black Hawk War of 1832 Archived June 19, 2009, at the Wayback Machine," Abraham Lincoln Digitization Project, Northern Illinois University, p. 2D. Retrieved 20 September 2007.

- ↑ Wisconsin State Historical Society, "8 July, Fort Gratiot, Mich.: Cholera Strikes Down Gen. Winfield Scott's Army."

- ↑ "The Driftless Area: An Inventory of the Regions Resources Archived October 17, 2007, at the Wayback Machine," 2000, Illinois Department of Natural Resources. Retrieved 8 August 2007.