| Bad Boy Bubby | |

|---|---|

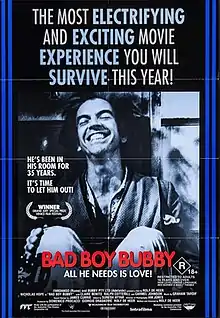

Australian daybill poster | |

| Directed by | Rolf de Heer |

| Written by | Rolf de Heer |

| Produced by |

|

| Starring |

|

| Cinematography | Ian Jones |

| Edited by | Suresh Ayyar |

| Music by | Graham Tardif |

Production companies | |

| Distributed by |

|

Release dates |

|

Running time | 114 minutes[1] |

| Countries |

|

| Languages |

|

| Budget | A$800,000[2] |

| Box office | A$808,789[3] |

Bad Boy Bubby is a 1993 black comedy film[4] written and directed by Rolf de Heer, and starring Nicholas Hope, Claire Benito, Ralph Cotterill, and Carmel Johnson.

Hope stars as the titular character, a mentally challenged man who has been held captive in his home by his abusive mother for his entire life. The storyline follows his escape from confinement, and subsequent journey of self-discovery. The film was shot on a low budget in Adelaide, and is an international co-production between Australia and Italy.[5]

Bad Boy Bubby premiered at the 50th Venice International Film Festival on 1 September 1993, where it won the Grand Jury Prize. It was released in Australia the following year, and was met with positive reviews. Although it was a box office failure, the film has gained a cult following.[6]

Plot

In an industrial area of Adelaide, Bubby is a mentally challenged 35-year-old man who lives in a squalid house with his abusive and religious fanatic mother, Florence. He has never left the house, due to his mother convincing him that the air outside is toxic, and Jesus will strike him down should he leave. He and his mother regularly have incestuous sex, with his mother often encouraging Bubby to fondle her breasts. The two have no other company except for a pet cat, which Bubby accidentally kills with clingwrap.

One night, Bubby's father Harold returns, having abandoned Florence years earlier to pursue a career as a preacher. Harold did not know he had a son, but he quickly comes to disdain Bubby, and mocks him for his presumed mental disorder. Harold beats Bubby, and encourages Florence to do so as well. Tired of the abuse, Bubby suffocates his parents with clingwrap, and decides to venture outside for the first time.

Bubby is picked up by members of The Salvation Army, and wanders into the town centre. He is harassed by members of the public for his social ineptitude and strange behaviour. He is later given a lift by a group of men who perform in a rock band, and he helps the band set up a gig. The band take a liking to Bubby, but are also unnerved by his odd actions. After reading a newspaper that reports on the murder of Bubby's parents, the band members decide to send him to stay with their friend Dan.

Dan and Bubby go out for dinner, but Bubby fondles a woman and is arrested. He is sent to jail, but is unwilling to talk with the warden. As punishment, he sends Bubby into a separate cell, where he is raped by another inmate, "The Animal". The prison chief then deems him to be rehabilitated, and lets him go.

Bubby enters a church, and converses with a man there, "The Scientist", who tells Bubby that God does not exist, and it is the job of humans to "think God out of existence" and take responsibility for themselves. Bubby goes to a pub and fondles another woman, and is beaten by her friends. Overwhelmed, Bubby returns to his home as he believes that there is no place for him in the world. He dons his father's clothes and assumes the personality of "Pop".

With newfound confidence, Bubby returns to town and finds a stray cat, who he vows to take care of. He goes to the club where the rock band are performing, and joins them on stage, where he delivers a bizarre performance, repeating phrases he has heard from various people. His performance is a success with the crowd, and he goes back to feed the cat, but is distraught to see that it has been killed by local hoodlums.

Upset, Bubby encounters a nurse named Angel, who cares for people with physical disabilities. They return to the care centre, and Bubby becomes infatuated with her breasts, as they remind him of his mother's. Angel and Bubby become lovers, and Bubby returns to performing with the rock band, becoming a sensation with audiences.

Angel invites him to have dinner with her strict and religious parents. Angel's parents humiliate her by mocking her weight, enraging Bubby, who curses at God in retaliation, before her parents demand he leave. Bubby kills Angel's parents with clingwrap, and the two continue their relationship. Finally at peace with himself, Bubby and Angel later have multiple children.

Cast

- Nicholas Hope as Bubby

- Claire Benito as Mam

- Ralph Cotterill as Pop

- Carmel Johnson as Angel

- Paul Philpot as Paul (band singer)

- Todd Telford as Little Greg (keyboards)

- Paul Simpson as Big Greg (drummer)

- Stephen Smooker as Middle Greg (bass)

- Peter Monaghan aa Steve (guitarist)

- Mark Brouggy as Mark (roadie)

- Bruce Gilbert as Dan

- Michael Constantinou as The Animal

- Alec Talbot as Prison Superintendent

- Norman Kaye as The Scientist

- Bridget Walters as Angel's Mother

- Graham Duckett as Angel's Father

- Grant Piro

Production background

Shortly after graduating from film school, Rolf de Heer collaborated with Ritchie Singer on the idea of what would eventually become Bad Boy Bubby. For most of the 1980s, de Heer collected ideas and wrote them on index cards. In 1987, he took a hiatus from making Bubby index cards, but in 1989 he resumed work. In 1989 or 1990 he saw the short film Confessor Caressor starring Nicholas Hope (which would eventually be included on the bonus DVD when Bad Boy Bubby was first released on DVD in 2004) and tracked him down. In 1991, de Heer began work on the actual script.

After he heard a rumour about the reintroduction of the death penalty to Australia, de Heer was angered and rewrote the ending so that Bubby would be executed at the end of the film. This ending was scrapped when the rumour proved false.

Filming took place in Port Adelaide between 30 November 1992 and 16 January 1993.

The people with cerebral palsy Bubby meets are not actors, but actual disabled people. Hope, who was raised Catholic, found the scenes where Bubby curses God in front of Angel's parents difficult to film.

Audio and visual innovation

Director de Heer describes the film as one large experiment, especially in the method used to record the dialogue: binaural microphones were sewn into the wig worn by leading actor Nicholas Hope, one above each ear. This method gave the soundtrack a unique sound that closely resembled what the character would actually be hearing. The film also used 31 individual directors of photography to shoot different scenes. Once Bubby leaves the apartment a different director of photography is used for every location until the last third of the film, allowing an individual visual slant on everything Bubby sees for the first time. No director of photography was allowed to refer to the work of the others.[7]

Animal cruelty allegation

When the film was released in Italy, a coalition of animal rights groups tried to set up a boycott of Australian products, alleging that Bubby's pet cat was wrapped in plastic wrapping and suffocated to death on film, but Rolf de Heer has said that none of that is true; the cat scenes were carefully filmed, with a veterinarian and animal cruelty inspector on set. Nicholas Hope, in an on-stage interview included on the DVD of the film, says there were two cats, one of which became a pet of a crew member. The other was a feral cat that was put down by a vet after filming (as with most feral cats that are caught in Australia).[8] Film critic Mark Kermode left the screening due to the apparent animal abuse in the making of the film.[9]

Awards

| Award | Category | Subject | Result |

|---|---|---|---|

| AACTA Awards (1994 AFI Awards)[10] |

Best Film | Giorgio Draskovic | Nominated |

| Domenico Procacci | Nominated | ||

| Rolf de Heer | Nominated | ||

| Best Direction | Won | ||

| Best Original Screenplay | Won | ||

| Best Actor | Nicholas Hope | Won | |

| Best Cinematography | Ian Jones | Nominated | |

| Best Editing | Suresh Ayyar | Won | |

| Seattle International Film Festival[11] | Golden Space Needle Award for Best Director | Rolf de Heer | Won |

| Valenciennes International Festival | Audience Award | Won | |

| Venice Film Festival[12] | FIPRESCI Prize | Won | |

| Grand Special Jury Prize | Won | ||

| Special Golden Ciak | Won | ||

| Golden Lion | Nominated | ||

Release

The film first screened in Australian cinemas on 28 July 1994, and was released on VHS by Roadshow Entertainment early the following year.

On 23 April 2007, Eureka Entertainment released Bad Boy Bubby on DVD for the UK market with all scenes intact. On the Blue Underground DVD, director Rolf de Heer claims that Bubby was the second highest-grossing film in Norway in 1995. In the UK, it was cut for cruelty to a cat.[13] The film was released on DVD in April 2005 in the United States by the Blue Underground company, and a special Two Disc Collectors' Edition was also released in Australia in June 2005 by Umbrella Entertainment. Umbrella reissued the film on Blu-ray in February 2021, newly remastered from the original negative. The Blu-ray contained all the special features from the 2005 DVD, plus a Q&A session with Nicholas Hope and Natalie Carr and a 25th anniversary commentary. The film had previously been released on Blu-ray in Australia in 2011, using the same transfer used for the 2005 DVD and containing all the special features from it.

Box office

Bad Boy Bubby grossed $808,789 at the box office in Australia.[3]

Bad Boy Bubby became a big hit in Norway, second only to Forrest Gump with Hope an actor in demand there.[14]

Reception

David Stratton, film critic for The Movie Show, praised Bad Boy Bubby. He awarded the film five stars out of five, remarking, "I really think this is one of the finest and most original of all Australian films that I've seen. I really think it's a milestone in Australian cinema".[15] It also holds a 100% approval rating on the review aggregation site Rotten Tomatoes, based on 10 reviews, with a weighted average of 7.9/10.[16]

See also

References

- ↑ "Bad Boy Bubby (18)". British Board of Film Classification. 19 August 1994. Retrieved 31 July 2013.

- ↑ Byrnes, Paul. "Bad Boy Bubby (1993)". Australian Screen Online. National Film and Sound Archive. Retrieved 15 November 2021.

- 1 2 "Film Victoria – Australian Films at the Australian Box Office" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 18 February 2011. Retrieved 10 October 2010.

- ↑ "Bad Boy Bubby (1993)". AllMovie. Retrieved 15 November 2021.

- ↑ "Italian producer sets up local production". The Age. 5 March 2002. Retrieved 16 August 2017.

- ↑ Buckmaster, Luke (16 May 2014). "Bad Boy Bubby: rewatching classic Australian films". The Guardian. Retrieved 14 November 2016.

- ↑ de Heer, Rolf (1993). "Directors Statement – London Film Festival". Archived from the original on 4 March 2008. Retrieved 12 April 2010.

- ↑ "Curator's notes Bad Boy Bubby (1993) on ASO – Australia's audio and visual heritage online". Aso.gov.au. Retrieved 18 December 2021.

- ↑ Hawkins, Jack (7 May 2020). "Retrospective: Bad Boy Bubby". Heyuguys.com. Retrieved 18 December 2021.

- ↑ "1994". www.aacta.org. Retrieved 11 June 2023.

- ↑ "Golden Space Needle History 1990–1999". www.siff.net. Retrieved 11 June 2023.

- ↑ "Bad Boy Bubby - Review - Photos - Ozmovies". www.ozmovies.com.au. Retrieved 11 June 2023.

- ↑ "Bad Boy Bubby". The Bedlam Files. Retrieved 11 June 2023.

- ↑ "Bad Boy Bubby re-visited". Janefreeburywriter.com.au. 1 December 2017. Retrieved 18 December 2021.

- ↑ "Bad Boy Bubby: Review". SBS Movies. Retrieved 5 January 2017.

- ↑ "Bad Boy Bubby". Rotten Tomatoes. Retrieved 23 February 2021.

Further reading

- Hartney, Christopher (December 2010). "Literature & Aesthetics" [On Popular Epicureanism: Relationships of Theme and Style in Harold and Maude and Bad Boy Bubby]. 20. University of Sydney: 168–179.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help)