Al-Zayadina (singular: Zaydani or Zidany, also called the Banu Zaydan) were an Arab clan based in the Galilee. They were best known after one of their sheikhs (chiefs) Zahir al-Umar, who, through his tax farms, economic monopolies, popular support, and military strength ruled a semi-autonomous sheikhdom in northern Palestine and adjacent regions in the 18th century.[1]

History

Origins

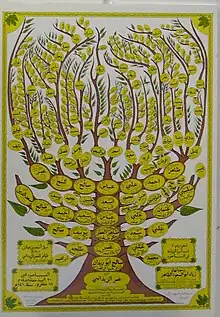

According to the historian Ahmad Hasan Joudah, the origins of the Zayadina are obscure, but that they were certainly of Arab tribal stock. Members of the clan claim descent from the great military leader Khalid ibn Al Waleed,[1]

During the early Ottoman period (1517–1917), members of the Zayadina lived in the vicinity of Maarrat al-Numan, a city on the main road between Damascus and Aleppo. They were a semi-nomadic and relatively small clan of roughly fifty persons and as such were under the protection of the larger Banu Asad tribe, according to Sabbagh.[1] However, Joudah notes there is no record of a Banu Asad tribe in the Levant at the time. Sabbagh maintains that from their base near Maarrat al-Numan, the Zayadina cultivated lucrative relationships with merchants from Aleppo and Damascus and the sheikh of the clan became wealthy enough to become a target of their Banu Asad protectors. The Zayadina were attacked by the latter and moved southward, eventually settling in Tiberias in the eastern Galilee.[2]

They were Sunni Muslims[3] and tribally affiliated with the Qays faction, in opposition to the Yaman.

Establishment in Galilee

The identity of the Zaydani sheikh who settled the family in Tiberias in the 17th century is not definitively known. A number of sources refer to him as 'Abu Zaydan'.[4] The first member of the dynasty to be attested in the historical record was Sheikh Umar al-Zaydani. His father was Sheikh Salih,[4] who was known to have developed a good reputation and a leadership role in the Shaghur subdistrict in the central Galilee. Umar's father or other ancestors had likely subleased iltizam (limited-term tax farms) in the area from the emirs of the Druze in Mount Lebanon from the Ma'n dynasty, who often held the iltizam of Safed.[5] The Zayadina evidently had a foothold in the Shaghur valley, wresting control of it from the Druze sheikh of nearby Sallama.[2] The Zayadina sacked Sallama sometime between 1688 and 1692.[3] Nine other Druze villages in the same vicinity were also destroyed, including Kammaneh and Dallata.[6]

Around 1698, Umar was appointed, in effect, the tax collector of the Safed muqata'a (fiscal district) by Bashir Shihab, a descendant of the Ma'ns from his mother's side who inherited the chieftainship of the Druze in Mount Lebanon and the iltizam, or limited-term tax farm, of Safed by the governor of Sidon. By 1703, Umar had grown powerful enough to be considered the "paramount sheikh of the Galilee" by the French vice-consul of Sidon, while his brothers Ali and Hamza were multazims in the western Lower Galilee and the vicinity of Nazareth, respectively, around this time.[7][lower-alpha 1]

Umar died in 1706 and was succeeded as head of the family by his eldest son, Sa'd.[9] The Zayadina were deposed from their iltizam by the governor of Sidon the following year, after the death of Bashir, but were restored by Bashir's successor, Haydar Shihab, when he defeated his Druze rivals for control of Bashir's former ilitizam in 1711.[8] Around 1707, the Zayadina were compelled to leave the Tiberias area, and were invited to settle elsewhere in the Galilee by the Banu Saqr tribe, which controlled the region west of Tiberias. Sa'd chose to live in Arrabat al-Battuf.[2]

Domination of the Galilee

The Zayadina expanded their iltizam and territory over much of the Galilee during the 1730s, with Sa'd's younger brother, Zahir al-Umar, emerging as the family's preeminent chief. He took over the town of Tiberias, gained its iltizam, and fortified it as his headquarters starting around 1730. Sa'd moved the family seat from Arraba to nearby Deir Hanna, which he considerably fortified. Their cousin Muhammad, the son of their uncle Ali, continued to dominate the area of Shefa-Amr from his father's headquarters in Damun. By 1740, Zahir and the family had gained the iltizam or otherwise imposed their control in Safed and its environs, Nazareth, the fortress of Jiddin and the coastal plain of Acre, and the fortress villages of Bi'ina in the Shaghur,[10] Deir al-Qassi, and Suhmata.[11]

The Zayadina under Zahir and Sa'd withstood sieges against their Tiberias and Deir Hanna headquarters in 1742 and 1743 by the governor of Damascus, Sulayman Pasha al-Azm, who had the support of the imperial government in Constantinople. The failure of the sieges and the subsequent, long-term détente reached with Sulayman Pasha's successor, As'ad Pasha al-Azm enabled Zahir to focus on capturing the strategic port village of Acre. He occupied it in 1744 and was granted its iltizam by 1746. In the process, he had his cousin Muhammad of Damun arrested and executed to remove him as a contender for influence in Acre.[12]

Intra-family conflict

Headquartered in Acre from 1750, Zahir installed his sons at strategic fortresses across the Galilee to safeguard his interests there, namely by keeping subordinate village chiefs in check and protecting his domains from Bedouin raids. While entrusting these commands to his sons was meant to guarantee his grip over the region, the sons eventually struggled against Zahir, and each other, for power and influence. Thie process intensified in the 1760s, as the sons sought to strengthen their positions in anticipation of their aging father's death.[13] Zahir's sons had different mothers and often drew on their maternal kinsmen in these disputes.[14] Zahir's three eldest sons, Salibi, Uthman, and Ali, all considered themselves their father's successor-in-waiting,[14] and the latter two in particular, were the main drivers of the rebellions for more territorial control.[15]

As early as 1753, Uthman rebelled and set up base in Jenin, a stronghold of the Zayadina's rival, the Jarrars. From there, he led intrigues against Zahir, who captured and exiled him to Egypt for an unclear period.[15] In 1761, Zahir detected a plot by Sa'd, hitherto his chief adviser and a key figure behind his successes, to topple and replace him, with the support of Uthman. Zahir persuaded Uthman to assassinate Sa'd in exchange for control of Shefa-Amr. Uthman killed Sa'd, but pleas by Shefa-Amr's residents caused Zahir to retract the appointment.[16] Backed by his full-brothers Ahmad and Sa'd al-Din, who were also angered by Zahir's refusal to cede them more territory, Uthman besieged Shefa-Amr in 1765. Under Zahir's instructions, the local residents successfully defended the town. The three brothers then appealed to Zahir's eldest and most loyal son, Salibi, who had been in charge of Tiberias since Sulayman Pasha's failed siege, to intervene on their behalf, but Salibi was unable to persuade Zahir to make concessions.[17]

The four brothers then attempted to rekindle their alliance with the Saqr, who Zahir had since been routed in the Marj Ibn Amer plain in 1762. Their efforts failed when Zahir bribed the tribe to withhold their support. He subsequently imprisoned Uthman in Haifa for six months before exiling him to a village near Safed.[17] In May 1766, Uthman renewed his rebellion against Zahir with backing from the Druze clans of the Galilee, but this coalition was defeated by Zahir.[18] Mediation by Isma'il Shihab of Hasbaya culminated in a peace summit near Tyre where Zahir and Uthman reconciled. Uthman was consequently granted control of Nazareth.[19]

In September 1767, a conflict between Zahir and his son Ali, who was headquartered in Safed, broke out over the former's refusal to cede control of the strategic fortress villages of Deir Hanna and Deir al-Qassi. Before the dispute, Ali had been loyal to Zahir and proven effective in helping him suppress dissent among his other sons and in battles against external enemies. Zahir's forces marched on Safed later that month, pressuring Ali to surrender. Zahir pardoned him and ceded Deir al-Qassi.[20] The intra-family conflict was renewed weeks later, with Ali and his brother Sa'id poised against Zahir and Uthman. Ibrahim Sabbagh, Zahir's financial adviser, brokered a settlement, whereby Sa'id was granted control over the villages of Tur'an and Hittin.[21]

Ali refused to negotiate, as he continued to seek control of Deir Hanna, which Zahir denied him. Ali gained Salibi's backing, and the two defeated their father, who had since demobilized his troops and was relying on local volunteers from Acre. Zahir remobilized his Maghrebi mercenaries in Acre and defeated Ali, who subsequently fled Deir Hanna in October. Out of sympathy for Ali's children, who remained in the fortress village, he pardoned him on the condition he pay 12,500 piasters and 25 Arabian horses for the fortress.[22] By December 1767, Zahir's intra-family disputes had subsided.[23]

The rebellions by Zahir's sons were nearly always backed by the governor of Damascus, Uthman Pasha, who sought to sustain the internal dissent to weaken Zahir.[24] The latter lodged complaints to the imperial government about Uthman Pasha's support for his rebellious sons at least once in 1765.[25] Zahir received the support of the governor of Sidon, Muhammad Pasha al-Azm, an opponent of Uthman Pasha who sought to restore the Azms to office in Damascus. While Sidon's support had no practical military value, the support of Zahir's nominal superior provided him with official legitimacy amid his family's insurrections.[26]

Descendants

In Haifa in the 19th and early 20th centuries, the al-Bashir al-Zaydani family, descendants of the Zayadina, were influential among Haifa's ulema (Muslim scholarly class) and its sharia (Islamic law) court.[27] The Bashirs' position among Haifa's religious offices dwindled by the 1880s and by then they had lost most of their properties.[28]

Many of the descendants of the Zayadina in modern-day Israel use the surname 'al-Zawahirah'[29] or 'Dhawahri'[30] in honor of Zahir (whose name is colloquially transliterated as 'Dhaher'). They mostly live in the Galilee localities of Nazareth, Bi'ina, Kafr Manda, and, before its depopulation in the 1948 Arab-Israeli war, the village of Damun.[31]

A member of the Zayadina, Yousef Abbas, settled in Amman in Transjordan in the late 17th century. Around three decades later, his family migrated to Irbid and were thenceforth called 'al-Tal' (the Hill). The family was named al-Tal because in Amman they had lived close to the town's citadel, which was built on a hill or tal. Yousef's four sons, Hussein, Hassan, Abd al-Rahman, and Abd al-Rahim and their modern-day descendants continue to use the surname al-Tal, sometimes with 'Yousef' as an antecedent.[32] From Irbid, members of the al-Tal family served in various Ottoman governmental positions in the 19th and early 20th centuries.[33] The family was involved in the establishment of the Emirate of Transjordan, a British protectorate under the nominal rule of Emir Abdullah and played important roles in its government. Prominent family members include a general of Jordan's Arab Legion, Abdullah al-Tal, and Jordanian Prime Minister Wasfi al-Tal and his father, the poet Mustafa Wahbi Tal.[34]

The Beverly Hills-based Palestinian American architect Mohamed Hadid, father of models Gigi, Bella and Anwar, claims descent from Zahir al-Umar through his mother's side.[35][36]

Notes

References

- 1 2 3 Joudah, 1987, p. 19.

- 1 2 3 Joudah, 1987, p. 20.

- 1 2 Firro, 1992, p. 45

- 1 2 Joudah 1987, p. 16.

- ↑ Joudah 1987, p. 17.

- ↑ Firro, 1992, p. 46

- ↑ Cohen 1973, pp. 8–9.

- 1 2 Cohen 1973, p. 9.

- ↑ Philipp 2001, p. 31.

- ↑ Philipp 2001, pp. 32–34.

- ↑ Joudah 2013, p. 20.

- ↑ Philipp 2001, pp. 34–36.

- ↑ Cohen 1973, pp. 84–85.

- 1 2 Joudah 2013, p. 59.

- 1 2 Cohen 1973, pp. 85–86.

- ↑ Joudah 2013, pp. 54–55.

- 1 2 Joudah 2013, p. 55.

- ↑ Joudah 2013, p. 56.

- ↑ Joudah 2013, pp. 56–57.

- ↑ Joudah 2013, p. 57.

- ↑ Joudah 2013, pp. 57–58.

- ↑ Joudah 2013, pp. 58–59.

- ↑ Joudah 2013, p. 60.

- ↑ Cohen 1973, p. 86.

- ↑ Cohen 1973, p. 44.

- ↑ Joudah 2013, p. 58.

- ↑ Agmon, 2006, p. 67

- ↑ Panzac, 1995, pp. 549-550.

- ↑ Joudah, 1987, p. 118.

- ↑ Srouji, 2003, p. 187

- ↑ Joudah, 1987, p. 121.

- ↑ Yitzhak, 2012, p. 21.

- ↑ Yitzhak, 2012, p. 22.

- ↑ Yitzhak, 2012, pp. 22-23.

- ↑ Tully, Shawn; Blank, J. B. (31 July 1989). "The Big Moneymen of Palestine Inc". Fortune. Archived from the original on 22 December 2015. Retrieved 17 June 2016.

- ↑ "The Radar People Surreal Estate Developer". ANGE – Angelo. Modern Luxury. August 2010. Archived from the original on 22 June 2016. Retrieved 17 June 2016.

Bibliography

- Agmon, Iris (1996). Family and Court: Legal Culture and Modernity in Late Ottoman Palestine. Syracuse University Press. ISBN 9780815630623.

- Cohen, Amnon (1973). Palestine in the 18th Century: Patterns of Government and Administration. Jerusalem: The Magnes Press. ISBN 978-0-19-647903-3.

- Firro, Kais (1992). A History of the Druzes. Vol. 1. BRILL. ISBN 9004094377.

- Joudah, Ahmad Hasan (1987). Revolt in Palestine in the Eighteenth Century: The Era of Shaykh Zahir Al-ʻUmar. Kingston Press. ISBN 9780940670112.

- Joudah, Ahmad Hasan (2013). Revolt in Palestine in the Eighteenth Century: The Era of Shaykh Zahir al-Umar (Second ed.). Gorgias Press. ISBN 978-1-4632-0002-2.

- Orser, Charles E. (1996). Images of the Recent Past: Readings in Historical Archaeology. Rowman Altamira. ISBN 9780761991427.

- Philipp, Thomas (2001). Acre: The Rise and Fall of a Palestinian City, 1730-1831. Columbia University Press. ISBN 9780231506038.

- Srouji, Elias S. (2003). Cyclamens from Galilee: Memoirs of a Physician from Nazareth. iUniverse, Inc. ISBN 9780595303045.

- Yitzhak, Ronen (2012). Abdullah Al-Tall, Arab Legion Officer: Arab Nationalism and Opposition to the Hashemite Regime. Apollo Books. ISBN 9781845194086.