| City Walls or Borough Walls | |

|---|---|

| Bath, Somerset in England | |

Remains of Bath's city walls | |

City Walls or Borough Walls | |

| Coordinates | 51°22′57″N 2°21′41″W / 51.3825028°N 2.3614444°W |

| Grid reference | grid reference ST751648 |

| Type | City wall |

| Site information | |

| Condition | Fragmentary remains |

| Site history | |

| Built | 3rd century |

| Materials | Stone |

| Fate | Almost entirely abandoned Partly preserved (at Upper Borough Walls and East gate remains)[1] |

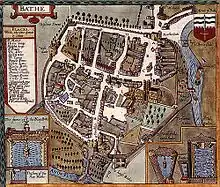

Bath's city walls (also referred to as borough walls) were a sequence of defensive structures built around the city of Bath in England. Roman in origin, then restored by the Anglo-Saxons, and later strengthened in the High medieval period, the walls formed a complete circuit, covering the historic core of the modern city, an area of approximately 23 acres (9.3 ha)[2] including the Roman Baths and medieval Bath Abbey. In the mid 18th century most of the town walls and gatehouses were demolished to accommodate the Georgian development of the town. However, the line of the walls can still be traced in the town's street layout.

History

Bath's first defensive walls were built by the Romans in the 3rd century CE to surround their settlement of Aquae Sulis.[3] By the 10th century CE, the Anglo-Saxons had established a fortified burh (borough) known as Acemannesceastre within the ruins of the former Roman town. The Saxons utilised the remains of the Roman walls in their own defence. These fortifications maintained Bath as a centre of regional power within Anglo Saxon Britain.[4] As the burh was located at the northern edge of the kingdom of Wessex, it would have guarded against neighbouring Mercia, which was part of the Danelaw in the 10the century CE.[5] During The Anarchy in the 12th century CE, the height of the stone walls was increased on the orders of the Norman king King Stephen.[6] Bath's medieval walls included four gates.

The North and South Gates within Bath's walls were both decorated with a number of statues, including the legendary King Bladud and Edward III.[7] The two gates were linked to local churches, St Mary's and St James' respectively.[8]

Demolition

The North and South Gates were demolished in 1755,[9] and the West Gate was demolished in the 1760s.[10] Only part of one of Bath's medieval gates still survives, the East Gate, located near Pulteney Bridge.[11] The remaining wall circuit is now protected as a Grade II listed building and a scheduled monument.

During the Second World War bomb damage uncovered parts of the city walls that had been built over by other buildings.[12] In 1980 a timber barricade was found close to the north city wall. This may have been erected in the Saxon era to allow repair of the stonework.[13][14] A sword from the late tenth or early 11th century was also found, which may date from a skirmish in 1013.[15]

Circuit

Starting at the Northgate and running anti-clockwise, the wall ran along the north side of the Upper Borough Walls street — Trim Street lies outside. A section of the wall was recently discovered below where Burton Street now crosses over the circuit.[17] After passing in front of the Theatre Royal, the wall then ran along the east side of Sawclose to the Westgate and continued down the east side of the street called Westgate Buildings.

The route of wall went through the now open space at St James's Rampire and then along the south side of the Lower Borough Walls street to the Southgate. Continuing anti-clockwise, the wall passed through the southern part of the Marks & Spencers building, where the Ham Gate was, and then through the buildings between (and running parallel to) Old Orchard Street and North Parade Buildings. The route continued along Terrace Walk and to the west of the Parade Gardens and passed under the back of The Empire. At Boat Stall Lane are the remains of the only remaining gate — the East Gate.[18] From here the wall passed under the Guildhall Market, Victoria Art Gallery and Bridge Street, before meeting the North Gate having passed under the buildings at the corner of Bridge Street and Northgate Street.

The route is marked on Ordnance Survey mapping of 1:10,000 scale and better, including on historic Ordnance Survey maps.

See also

References

- ↑ "Historic England Research Records". Heritage Gateway. Retrieved 18 July 2022.

- ↑ Mayor of Bath Archived 25 December 2019 at the Wayback Machine Roman Bath

- ↑ Creighton and Higham, p.60.

- ↑ Creighton and Higham, p.36.

- ↑ Creighton and Higham, p.57.

- ↑ Davenport pages 91-92

- ↑ Creighton and Higham, pp.141-142.

- ↑ Creighton and Higham, p.177.

- ↑ Creighton and Higham, p.141.

- ↑ "The History of Kingsmead Square" (PDF). Bath and North East Somerset Council. 26 September 2018. Retrieved 30 September 2018.

- ↑ Creighton and Higham, p.254.

- ↑ Creighton and Higham, p.246.

- ↑ Manco, Jean. "Alfred's Borough". Bath Past. Retrieved 10 October 2011.

- ↑ O'Leary, T.J. "Excavations at Upper Borough Walls, Bath, I 980" (PDF). Archaeology Data Service. Archived from the original (PDF) on 13 June 2011. Retrieved 24 October 2009.

- ↑ Davenport pages 62-63

- ↑ Davenport, Peter (2002). Medieval Bath Uncovered. Stroud: Tempus. ISBN 0-7524-1965-X.

- ↑ "Sewer workers in Bath reveal part of Roman city's walls". BBC. Retrieved 27 September 2013.

- ↑ Historic England. "East Gate (1394942)". National Heritage List for England. Retrieved 4 April 2015.

Bibliography

- Creighton, Oliver Hamilton and Robert Higham. (2005) Medieval Town Walls: an Archaeology and Social History of Urban Defence. Stroud, UK: Tempus. ISBN 978-0-7524-1445-4.

- Davenport, Peter (2002). Medieval Bath Uncovered. Stroud: Tempus. pp. 62–63. ISBN 0-7524-1965-X.