Bathsheba Bowers | |

|---|---|

| Born | June 4, 1671 |

| Died | 1718 (aged 46) |

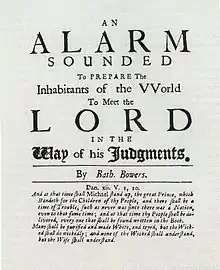

| Notable work | An Alarm Sounded to Prepare the Inhabitants of the World to Meet the Lord in the Way of His Judgments |

| Relatives | Henry Dunster (uncle) |

Bathsheba Bowers (June 4, 1671 – 1718)[1] was an American Quaker author and preacher. Her only surviving work is the spiritual autobiography An Alarm Sounded to Prepare the Inhabitants of the World to Meet the Lord in the Way of His Judgments (1709).

Biography

Bowers was one of twelve children of Quakers Benanuel Bowers and Elizabeth Dunster Bowers, the niece of Henry Dunster, first president of Harvard University. Her parents were from England and immigrated to America, settling in Charlestown, Massachusetts, where Bowers was born and raised. Anti-Quaker persecution prompted the Bowers family to send their four eldest daughters to Philadelphia, which had a large Quaker population.[1][2] Bowers never married, though her sisters did, and the diary of Ann Bolton née Curtis, the daughter of Bowers' sister Elizabeth who lived with the Bowers family for a brief time, provides what little biographical information is known of Bowers outside of her own writing.[1][3]

In Philadelphia, Bowers was noted for her eccentricity.[4] Near a spring, she built a small home that the locals called "Bathsheba's Bower" or "Bathsheba's folly" and lived as a recluse. She cultivated her garden and adopted the principles of vegetarian Thomas Tryon.[2] She professed Quakerism but had a deep argumentative and independent streak. According to Bolton, Bowers was "so Wild in her Notions it was hard to find out what religion she really was of".[3]

An Alarm was likely published in New York by Quaker printer William Bradford in 1709.[1] In the work, she presents her life as a series of tests designed by God for her to overcome and outlines her spiritual progress overcoming them.[4] While An Alarm adheres to many of the conventions of Quaker spiritual autobiographies, its tone is that of what one critic describes as "a woman always emotionally on edge".[1] Jill Lepore of The New Yorker writes, "The only book that year [1709] written by a woman, it's twenty-two pages long, and Bowers spends a good three of them apologizing for having written it.[5]

Bowers published an unknown number of other works, including a biography.[1] The public response, if any, to her work is also unknown.[4] She received no attention from scholars until the late 20th century, especially after her inclusion in the Heath Anthology of American Literature (1990).[1]

When she was thirty-five, Bowers moved to South Carolina, where there was a growing Quaker population.[1] According to Bolton, Bowers believed she could not die.[3] Bolton wrote of an Indian attack:

... the Indians Early one morning surprised the place - killed and took Prisoners several in the house adjoining to her. Yet she moved not out of her Bed, but when two Men offered their assistance to carry her away, she said Providence would protect her, and indeed so it provided at the time, for those two men no doubt by the Direction of providence took her in her Bed for she could not rise, conveyed her into their Boat and carried her away in Safety tho' the Indians pursued and shot after them.[3]

Bowers, however, eventually did die in South Carolina at the age of 46.[1]

See also

- Benjamin Loxley house

References

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 Petrulionis, Sandra Harbert (1998). "Bathsheba Bowers". Dictionary of Literary Biography: American Women Prose Writers to 1820. Vol. 200. pp. 62–66.

- 1 2 Jane Stevenson; Peter Davidson (2001). Early Modern Women Poets (1520-1700): An Anthology. Oxford University Press. p. 508. ISBN 978-0-19-924257-3. Retrieved 20 February 2013.

- 1 2 3 4 Potts, William J. (1879). "Notes and Queries: Bathsheba Bowers". Pennsylvania Magazine of History and Biography. 3 (1): 110–12. JSTOR 20084389.

- 1 2 3 Krieg, Joann Peck (1979). "Bathsheba Bowers". In Mainiero, Lina (ed.). American Women Writers: A Critical Reference Guide from Colonial Times to the Present. Vol. 1. New York: Frederick Ungar Publishing Co. pp. 204–05.

- ↑ Lepore, Jill (2009-12-07). "The Top Ten Books of 1709". The New Yorker.