| Battle of Ball's Bluff | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the American Civil War | |||||||

Depiction of Ball's Bluff by Alfred W. Thompson | |||||||

| |||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

|

|

| ||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

|

Charles Pomeroy Stone Edward Dickinson Baker † | Nathan G. Evans | ||||||

| Strength | |||||||

| 1,720 | 1,709 | ||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||

| 921–1,002 total[1][lower-roman 1] | 155 (36 killed; 117 wounded; 2 captured)[2][3] | ||||||

The Battle of Ball's Bluff was an early battle of the American Civil War fought in Loudoun County, Virginia, on October 21, 1861, in which Union Army forces under Major General George B. McClellan suffered a humiliating defeat.

The operation was planned as a minor reconnaissance across the Potomac to establish whether the Confederates were occupying the strategically important position of Leesburg.[4][lower-roman 2] A false report of an unguarded Confederate camp encouraged Brigadier General Charles Pomeroy Stone to order a raid, which resulted in a clash with enemy forces. A prominent U.S. Senator in uniform, Colonel Edward Baker, tried to reinforce the Union troops, but failed to ensure that there were enough boats for the river crossings, which were then delayed. Baker was killed,[5] and a newly arrived Confederate unit routed the rest of Stone's expedition.

The Union losses, although modest by later standards, alarmed Congress, which set up the Joint Committee on the Conduct of the War, a body which would provoke years of bitter political infighting.

Background

Three months after the First Battle of Bull Run, Major General George B. McClellan was building up the Army of the Potomac in preparation for an eventual advance into Virginia. On October 19, 1861, McClellan ordered Brigadier General George A. McCall to march his division to Dranesville, Virginia, twelve miles southeast of Leesburg, in order to discover the purpose of recent Confederate troop movements which indicated that Colonel Nathan "Shanks" Evans might have abandoned Leesburg. Evans had, in fact, left the town on October 16–17 but had done so on his own authority. When Confederate Brigadier General P.G.T. Beauregard expressed his displeasure at this move, Evans returned. By the evening of October 19, he had taken up a defensive position on the Alexandria-to-Winchester Turnpike (modern-day State Route 7) east of town.

McClellan came to Dranesville to consult with McCall that same evening and ordered McCall to return to his main camp at Langley, Virginia, the following morning. However, McCall requested additional time to complete some mapping of the roads in the area and, as a result, did not actually leave for Langley until the morning of October 21, just as the fighting at Ball's Bluff was heating up.

On October 20, while McCall was completing his mapping, McClellan ordered Brigadier General Charles Pomeroy Stone to conduct what he called "a slight demonstration"[6] in order to see how the Confederates might react.[7] Stone moved troops to the river at Edwards Ferry, positioned other forces along the river, had his artillery fire into suspected Confederate positions, and briefly crossed about a hundred men of the 1st Minnesota[8] to the Virginia shore just before dusk. Having gotten no reaction from Colonel Evans with all of this activity, Stone recalled his troops to their camps and the "slight demonstration" came to an end.

Stone then ordered Colonel Charles Devens of the 15th Massachusetts Infantry, stationed on Harrison's Island, facing Ball's Bluff, to send a patrol across the river at that point to gather what information it could about enemy deployments. Devens sent Captain Chase Philbrick and approximately 20 men to carry out Stone's order. Advancing in the dark nearly a mile inland from the bluff, the inexperienced Philbrick mistook a row of trees for the tents of a Confederate camp and, without verifying what he saw, returned and reported the existence of a camp. Stone immediately ordered Devens to cross some 300 men and, as soon as it was light enough to see, attack the camp and, per his orders, "return to your present position."

This was the genesis of the Battle of Ball's Bluff. Contrary to the long-held traditional interpretation, it did not come from a plan by either McClellan or Stone to take Leesburg. The initial crossing of troops was a small reconnaissance. That was followed by what was intended to be a raiding party.[9] To make matters worse, Stone was not advised that McCall and his division had been ordered back to Washington.[10]

Opposing forces

Union

Confederate

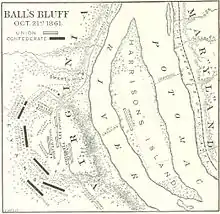

Battle

On the morning of October 21, Colonel Devens' raiding party discovered the mistake made the previous evening by the patrol; there was no camp to raid.[11] Opting not to recross the river immediately, Devens deployed his men in a tree line and sent a messenger back to report to Stone and get new instructions. On hearing the messenger's report, Stone sent him back to tell Devens that the remainder of the 15th Massachusetts (another 350 men) would cross the river and move to his position. When they arrived, Devens was to turn his raiding party back into a reconnaissance and move toward Leesburg.

While the messenger was going back to Col. Devens with this new information, Colonel and U.S. Senator Edward Dickinson Baker showed up at Stone's camp to find out about the morning's events. He had not been involved in any of the activities to that point. Stone told him of the mistake about the camp and about his new orders to reinforce Devens for reconnaissance purposes. He then instructed Baker to go to the crossing point, evaluate the situation, and either withdraw the troops already in Virginia or cross additional troops at his discretion.[4]

On the way upriver to execute this order, Baker met Devens' messenger coming back a second time to report that Devens and his men had encountered and briefly engaged the enemy, one company (Co. K) of the 17th Mississippi Infantry. Baker immediately ordered as many troops as he could find to cross the river, but he did so without determining what boats were available to do this. A bottleneck quickly developed so that Union troops could only cross slowly and in small numbers, making the crossing last throughout the day.

Meanwhile, Devens's men (now about 650 strong) remained in its advanced position and engaged in two additional skirmishes with a growing force of Confederates, while other Union troops crossed the river but deployed near the bluff and did not advance from there.[12] Devens finally withdrew around 2:00 p.m. and met Baker, who had finally crossed the river half an hour later. Beginning around 3:00 the fighting began in earnest and was almost continuous until just after dark.

Col. Baker was killed at about 4:30 p.m. and remains the only United States Senator ever killed in battle. Following an abortive attempt to break out of their constricted position around the bluff, the Federals began to recross the river in some disarray. Shortly before dark, a fresh Confederate regiment (the 17th Mississippi) arrived and formed the core of the climactic assault that finally broke and routed the Union troops.

Many of the Union soldiers were driven down the steep slope at the southern end of Ball's Bluff (behind the current location of the national cemetery) and into the river. Boats attempting to cross back to Harrison Island were soon swamped and capsized. Many Federals, included some of the wounded, were drowned. Bodies floated downriver to Washington and even as far as Mount Vernon in the days following the battle. A total of 223 Federals were killed, 226 were wounded, and 553 were captured on the banks of the Potomac later that night. The official records incorrectly state that only 49 Federals were killed at this battle, an error probably resulting from a mistaken reading of the report of the Union burial detail which crossed over the next day under flag of truce.[1] Fifty-four Union dead—of whom only one is identified—are buried in Ball's Bluff Battlefield and National Cemetery.[13] A Union howitzer captured by Confederate forces was recaptured May 29, 1863 from John S. Mosby raid at Greenwich, Virginia.[14]

The engagement is also known as the Battle of Harrison's Island or the Battle of Leesburg.

Aftermath

This Union defeat was relatively minor in comparison to the battles to come in the war, but it had an enormously wide impact in and out of military affairs.[15] In addition to losing 223 soldiers, the Union lost a sitting senator, which led to severe political ramifications in Washington. Stone was treated as the scapegoat for the defeat, but members of Congress suspected that there was a conspiracy to betray the Union. The ensuing outcry, and a desire to learn why Federal forces had lost battles at Bull Run (Manassas), Wilson's Creek, and Ball's Bluff, led to the establishment of the Congressional Joint Committee on the Conduct of the War, which would bedevil Union officers for the remainder of the war (particularly those who were Democrats) and contribute to nasty political infighting among the generals in the high command.

Lt. Oliver Wendell Holmes Jr., of the 20th Massachusetts Volunteer Infantry, survived a nearly fatal wound at Ball's Bluff to become an Associate Justice of the Supreme Court of the United States in 1902. Herman Melville's poem "Ball's Bluff – A Reverie" (published in 1866) commemorates the battle. Holmes' great friend and role model, Lt. Henry Livermore Abbott also survived the battle but did not survive the war. In 1865, Abbott was posthumously promoted to Brigadier General. Another outstanding young officer named Edmund Rice also eventually reached the rank of Brigadier General, was awarded the Medal of Honor and was fortunate enough to survive the war by near a half century. 2nd Lt. John William Grout of the 15th Massachusetts was killed in the battle; his death inspired a poem (and later a song) titled "The Vacant Chair".

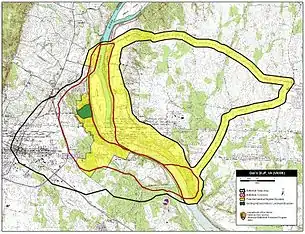

Battlefield preservation

The site of the battle is preserved as the Ball's Bluff Battlefield and National Cemetery, which was declared a National Historic Landmark in 1984.[16] The park is maintained by the Northern Virginia Regional Park Authority.[17] The battlefield area has been restored over time to look much like it did in 1861. Interpretive tours are given by volunteer guides throughout the spring, summer and fall each weekend at 11 AM and 1 PM. The Civil War Trust (a division of the American Battlefield Trust) and its partners have acquired and preserved 3 acres (0.012 km2) of the battlefield.[18]

In culture

Bernard Cornwell's Copperhead, the second installment of The Starbuck Chronicles, begins with the Battle of Ball's Bluff. The fictional Faulconer Legion is placed at the left flank of the Confederate position and led by Captain Starbuck's K Company, begins the rout of the Union forces.[19]

Geraldine Brooks' March, winner of the 2006 Pulitzer Prize for Fiction, also opens with the Battle of Ball's Bluff.[20] Mr. March, the father in Louisa May Alcott's Little Women, is the chaplain serving with the Union army.

Along the Chesapeake and Ohio Canal on the Maryland side, it was rumored that ghosts of departed soldiers from that battle, particularly those who drowned in one of the boats that sank in the Potomac River, haunted that area, so canal workers did not stay in that area overnight, and tied up their boats for the night elsewhere.[21]

The poem, "The Vacant Chair" was written by Henry S Washburn to commemorate the death of Lt. John William Grout of the 15th Massachusetts Infantry, who was killed at the Battle of Ball's Bluff. It was set to music by George F. Root and was popular in the North and South due to its universal message of loss.

American historian and curator, David C. Ward penned a poem in 2014 titled, Balls Bluff.

Footnotes

- ↑ The number of Union casualties from this battle vary by source. The Medical and Surgical History of the Civil War reports 223 Federals killed, 226 wounded, and 553 captured; Garrison (pp. 115–6.) gives 49 killed, 198 wounded, 529 missing, and 100+ drowned; Eicher (p. 127) gives 49 killed, 158 wounded, and 714 captured/missing; Winkler (p. 46) gives 49 killed, 158 wounded, 553 captured, and 100+ drowned.

- ↑ Leesburg was a regional transportation hub. It was the northwestern terminus of the Alexandria, Loudoun & Hampshire Railroad which ran along or near the Potomac River from Alexandria, Virginia which is across the river from Washington, D.C. Johnston, II, Angus James. Virginia Railroads in the Civil War. Chapel Hill, NC: The University of North Carolina Press, 1961. OCLC 977752. p. 93. Control of the nearby fords and ferries was the key to controlling north or south invasion routes. Meserve, Stevan F. The Civil War in Loudoun County, Virginia: A History of Hard Times. With a Chapter on Ball's Bluff by James A. Morgan, III. Charleston, SC: The History Press, 2008. ISBN 978-1-59629-378-6. p. 31.

Notes

- 1 2 Barnes (1991), p. XXXVIII - Table XXXVIII

- ↑ Winkler (2008), p. 46.

- ↑ NPS Ball's Bluff.

- 1 2 ABT, Ball's Bluff, October 21, 1861.

- ↑ ABT, 10 Facts: Ball's Bluff.

- ↑ Eicher, McPherson & McPherson (2001), p. 125; Garrison (2001), p. 110.

- ↑ AHF, Ball's Bluff (2005).

- ↑ Ballard (2001), p. 7.

- ↑ Morgan (2004), pp. 73–76.

- ↑ Sears (1999), pp. 33–34.

- ↑ ABT, Ball's Bluff, Harrison's Island.

- ↑ ABT, Battle of Ball's Bluff Map.

- ↑ Holien (1995), p. 141.

- ↑ Moore & Everett (1864), pp. 75–76.

- ↑ Morgan (2005), p. 38.

- ↑ Bearss (1984), p. 3.

- ↑ NOVA Parks, Ball's Bluff.

- ↑ ABT, Saved Land - Ball's Bluff Battlefield.

- ↑ Cornwell (1994), p. 15.

- ↑ Brooks (2006), pp. 3–10.

- ↑ Hahn (1996), pp. 68–69.

References

- Ballard, Ted (2001). Battle of Ball's Bluff, CMH Pub 35-1-1 (PDF). Staff Ride Guide (1st ed.). Washington, DC: U.S. Army Center of Military History. pp. 36–48. LCCN 2001037180. GPO SerNo 008-029-00372-4. Retrieved April 23, 2008.

- Barnes, Joseph K. (1991). Robertson, James I. Jr. (ed.). The Medical and Surgical History of the Civil War. Vol. VII (Broadfoot ed.). Wilmington, NC: Broadfoot Publishing Company. pp. XXXVIII, CXLI, 113. ISBN 978-0-916107-86-4. OCLC 24505335. Retrieved April 23, 2012.

- Eicher, David J.; McPherson, James M.; McPherson, James Alan (2001). The Longest Night: A Military History of the Civil War (PDF) (1st ed.). New York, NY: Simon & Schuster. pp. 125–128, 150. ISBN 978-0-7432-1846-7. LCCN 2001034153. OCLC 231931020. Retrieved April 23, 2008.

- Garrison, Webb Black Jr. (2001). Strange Battles of the Civil War (PDF). Nashville, TN: Cumberland House Publishing. pp. 109–124. ISBN 978-1-58182-226-7. OCLC 47844498. Retrieved April 23, 2012.

- Holien, Kim Bernard (1995) [1985]. Battle at Ball's Bluff (third printing ed.). Orange, VA: Publisher's Press. ISBN 0-943522-10-2. OCLC 29390540. Retrieved April 23, 2012.

- Moore, Frank; Everett, Edward, eds. (1864). The Rebellion Record: A Diary of American Events, with Documents, Narratives, Illustrative Incidents, Poetry, Etc. Vol. 7. New York, NY: G.P. Putnam, D. Van Nostrand. pp. 75–76. OCLC 6753869. Retrieved April 23, 2012.

- Morgan, James A. III (2004). A Little Short of Boats: The Fights at Ball's Bluff and Edwards Ferry, October 21-22, 1861: A History and Tour Guide (PDF) (1st ed.). Ft. Mitchell, KY: Ironclad Pub. pp. 73–76. ISBN 0-9673770-4-8. LCCN 2004020289. OCLC 1310733886. Retrieved June 12, 2006.

- Morgan, James A. III (November 2005). "Ball's Bluff: "A Very Nice Little Military Chance"". America's Civil War. HISTORYNET, LLC. 18 (5): 30–56. ISSN 1046-2899. Retrieved March 20, 2023.

- Sears, Stephen W. (1999). Controversies and Commanders: Dispatches from the Army of the Potomac (PDF) (1st ed.). Boston, MA: Houghton Mifflin. pp. 33–34. ISBN 978-0-585-15939-3. LCCN 98037736. OCLC 44959009. Retrieved April 23, 2008.

- Winkler, H. Donald (2008). Civil War Goats and Scapegoats (PDF) (1st ed.). Nashville, TN: Cumberland House Publishing. pp. 39–52. ISBN 978-1-58182-631-9. LCCN 2007049219. OCLC 1200277042. Retrieved April 23, 2012.

- "Disaster at Ball's Bluff, 21 October 1861". The Army Historical Foundation. The Army Historical Foundation. December 28, 2005. Retrieved June 12, 2006.

- "10 Facts: The Battle of Ball's Bluff". www.battlefields.org. American Battlefield Trust. January 13, 2009. Retrieved June 14, 2013.

- "Ball's Bluff, October 21, 1861". www.battlefields.org. American Battlefield Trust. January 13, 2009. Retrieved June 14, 2013.

- "Ball's Bluff, Harrison's Island". www.battlefields.org. American Battlefield Trust. January 13, 2009. Retrieved October 8, 2022.

- "Ball's Bluff Battlefield". www.battlefields.org. American Battlefield Trust. January 13, 2009. Retrieved December 26, 2018.

- "Battle of Ball's Bluff". www.battlefields.org. American Battlefield Trust. January 13, 2009. Retrieved June 14, 2013.

- "Ball's Bluff". nps.gov. U.S. National Park Service. 2012. Retrieved June 14, 2013.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain. - Bearss, Edwin C. (February 8, 1984). "National Register of Historic Places Inventory-Nomination: Ball's Bluff Battlefield and National Cemetery". nps.gov. U.S. National Park Service. Retrieved June 14, 2013.

- "Ball's Bluff Battlefield Regional Park". www.nvrpa.org. Northern Virginia Regional Park Authority. 2016. Archived from the original on March 28, 2016. Retrieved December 26, 2018.

- Brooks, Geraldine (2006). March (PDF) (Paperback ed.). London, UK: Harper Perennial. pp. 3–10, 277. ISBN 978-0-00-716587-2. OCLC 891789444. Retrieved April 14, 2013.

- Cornwell, Bernard (1994). Copperhead (PDF). The Starbuck Chronicles (1st ed.). New York, NY: Harper Collins Publishers. pp. 7–22. ISBN 0-06-017766-7. LCCN 93029421. OCLC 1310586481. Retrieved April 14, 2013.

- Hahn, Thomas F. (1996). Towpath Guide to the Chesapeake and Ohio Canal (11th ed.). Shepherdstown, WV: American Canal & Transportation Center. pp. 68–69. ISBN 978-0-933788-66-4. OCLC 59716841. Retrieved April 14, 2013.

Further reading

- Farwell, Byron (1990). Ball's Bluff: A Small Battle and Its Long Shadow (1st ed.). McLean, VA: EPM Publications. pp. 1–232. ISBN 978-0-939009-36-7. LCCN 90030049. OCLC 1043694748. Retrieved April 23, 2008.

- David C. Ward, Call Waiting. Poems (Manchester, England: Carcanet Press, 2014) (Has a poem titled Ball's Bluff)