| Battle of Caishi | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the Jin–Song Wars | |||||||

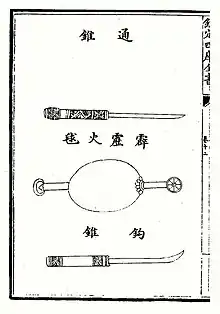

Song dynasty river ship armed with a trebuchet catapult on its top deck, from the Wujing Zongyao | |||||||

| |||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

| Jin dynasty | Southern Song dynasty | ||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

| Wanyan Liang † |

Chen Kangbo (prime minister / navy) Yu Yunwen (army commander) | ||||||

| Strength | |||||||

| 40,000[1] | 18,000[1] | ||||||

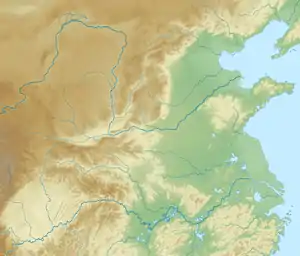

Location within Northern China | |||||||

The Battle of Caishi (Chinese: 采石之戰) was a major naval engagement of the Jin–Song Wars of China that took place on November 26–27, 1161. It ended with a decisive Song victory, aided by their use of gunpowder weapons.

Soldiers under the command of Wanyan Liang, the emperor of the Jurchen-led Jin dynasty, tried to cross the Yangzi River to attack the Southern Song dynasty.

Chen Kangbo, prime minister of the Song dynasty, was chief military strategist and commanded the navy. Yu Yunwen, a civil official, commanded the defending Song army. The paddle-wheel warships of the Song fleet, equipped with trebuchets that launched incendiary bombs made of gunpowder and lime, decisively defeated the light ships of the Jin navy.

Overview

Starting in 1125, the Jin had conquered former Song territories north of the Huai River. In 1142, a peace treaty settled the border between the two states, putting the Jin in control of northern China and the Song in control of the south. In 1150, Wanyan Liang became emperor and planned to unite northern and southern China under a single emperor. In 1158, he asserted that the Song had violated the 1142 treaty, a pretext for declaring war on the Song. He prepared for the war in the following year. He instituted a draft where all able-bodied men were required to enlist. The draft was unpopular, precipitating revolts that were later suppressed. The Jin army left the capital of Kaifeng on October 15 1161, and pushed through from the Huai to the Yangzi.

The Song were fortified along the Yangzi front. Wanyan Liang planned to cross the river at Caishi (modern day Ma'anshan), south of modern-day Nanjing. He embarked from the shore of the Yangzi on November 26, and clashed with Song forces led by Yu Yunwen and Chen Kangbo in a naval engagement. Wanyan Liang lost the battle and retreated to Yangzhou.

Wanyan Liang was assassinated in a military camp by his own soldiers shortly after the battle at Caishi. A military coup had taken place in the Jin court while Wanyan Liang was absent, enthroning Emperor Shizong as the new emperor. A peace treaty signed in 1165 ended the conflict between Song and Jin.

At Caishi, the Song led an army of 18,000, whereas Wanyan Liang reportedly led an army of 600,000 Jin soldiers. Over the course of the battle, many Jin soldiers deserted—bringing down the total Jin force—as they realized their northern steppe cavalry was inadequate for naval battles on rivers and lakes. The Song won mainly through its superior navy, gunpowder, and firearms. The victory boosted the morale of the Song infantry and pushed back the southern advance of the Jin army.[2]

Background

Jin-Liao-Song

The Song (960–1276) was a Han-led dynasty that ruled over Southeast China.[3] To their north was the Jin dynasty, a Jurchen-Han mixed dynasty that ruled over Northeast China. The Jin were led by the Jurchens, a confederation of semi-agrarian tribes from Manchuria in northeast China, though many northern Han nobles were also part of the Jin.[4] The Liao were a Khitan-led dynasty covering parts of Mongolia, West China, and Central Asia. Like the Jin, the Liao also adopted Han culture, spoke Chinese, and practiced Buddhism.

The Song and Jin had once been military allies. However, in 1114, the Jurchen, unified under the rule of Wanyan Aguda, plotted a revolt against their former overlords: the Khitan-led Liao dynasty.[4] In 1115, Aguda established the Jin dynasty and adopted the title of emperor.[5] The Jin negotiated a joint attack with the Song against the Khitans. They planned the attack for 1121 and then rescheduled to 1122.[6]

In 1122, the Jin captured the Khitan Supreme and Western Capitals. The Song tried to capture the Liao Southern Capital of Yan (modern Beijing), but it fell later that year to the Jin.[7] Negotiations between the Song and Jin produced a treaty in 1123, but bilateral relations deteriorated because of territorial disputes over the Sixteen Prefectures.[8][7] In 1125, the Jin invaded the Song.[9][4]

Start of Jin-Song wars

By 1127, Jin had unified most of northern China and besieged the Song capital of Kaifeng twice.[4][10] In the second siege of Kaifeng, Emperor Qinzong of the Song was captured. The Jin took him and the Song royal family to Northeast China as hostages.[11] Members of the Song court who had evaded capture fled south, where they established a temporary capital, first in the Song southern capital (modern Shangqiu),[7][12] and then in Hangzhou in 1129.[13]

The move of the Song capital south to Hangzhou signalled the transition from the Northern Song era to the Southern Song.[4] Qinzong's younger brother, Prince Zhao Gou, was enthroned as Qinzong's successor in the southern capital in 1127. Zhao is known posthumously as Emperor Song Gaozong.[14] The Jin general Wuzhu crossed the Yangzi River in 1130 and tried to capture Gaozong, but the Emperor escaped.[15][16] Wuzhu retreated north across the Yangzi, where he fought off a stronger Song fleet commanded by Han Shizhong.[17]

The Jin persisted with their advance into the remaining Song territories south of the Yangzi.[18] They faced an insurgency of Song loyalists in the north, the deaths of some important leaders, and military offensives by Song generals like Yue Fei. The Jin created the puppet government of Da Qi (大齊) to serve as a buffer state between Song and Jin, but Qi failed to defeat the Song.[19] The Jin abolished Qi in 1137. As the Jin gave up advancing south, diplomatic talks for a peace treaty resumed.[20]

Signed in 1142, the Treaty of Shaoxing established the boundary between the two states along the Huai River, which runs north of the Yangzi.[21][4] The treaty forbade the Song from purchasing horses from the Jin, but smuggling continued in the border markets.[22] The relations between the two states were mostly peaceful from 1142 to 1161, the year Wanyan Liang went to war.[23]

Jin preparations for Caishi

Wanyan Liang was crowned Jin emperor in 1150 after killing his cousin and predecessor, Emperor Xizong, in a palace coup.[24] Wanyan Liang considered himself more of a Han authoritarian emperor than a Jurchen leader who ruled through a tribal council.[25] The History of Jin contends that Wanyan Liang told his officials that the three desires of his life were conquest, absolute power, and women.[26] His ultimate ambition was to rule over all of China, not just the north.[27] In his childhood, Wanyan Liang adopted Song practices like drinking tea by learning from Song emissaries, and once he had become emperor, he pursued a policy of sinicizing (汉化) the state. His affinity for Song culture earned him the Jurchen nickname of 'Han imitator'. He moved the Supreme Capital of the Jin from Huining in the northeast to Beijing and promoted Kaifeng to his Southern Capital in 1157. He also moved government institutions south, tore down palaces of Jurchen chieftains in Manchuria, and constructed new palaces in Beijing and Kaifeng.[27] He made plans to move the Jin capital further south to the center of China.[28] Wanyan Liang's construction projects drained the Jin treasury.[28][27]

Plans for a war against the Southern Song began in 1158. That year, Wanyan Liang claimed that the Song had broken the 1142 treaty that banned them from acquiring horses. In 1159, he began building up his army in preparation for an invasion. He acquired weapons, which he stored in Beijing, as well as horses allegedly numbering 560,000.[27] Wanyan Liang understood that an invasion of the Song would require a lot of men. He ensured that Han soldiers were drafted into the war effort alongside Jurchen soldiers. The recruitment drive lasted until 1161.[27]

Naval confrontations were likely because the Jin planned on traveling by river. Ships were seized for the war and 30,000 of the recruits were assigned to the Jin fleet.[29] Wanyan Liang authorized the building of ships for the war in March 1159, under the auspices of the Ministry of War. Construction began in the Tong (通) prefecture near Beijing.[30] Wanyan Liang appointed himself head of the army and took personal command of the Jin forces.[31] The draft was unpopular. Several revolts erupted against it, many of them in the Jin provinces neighboring the Song.[27] But Wanyan Liang allowed no dissent; he had his stepmother executed after hearing that she was critical of the war effort.[31]

In order to eliminate any challenge to his legitimacy as emperor of a united China, Wanyan Liang ordered the execution of all male members of the Song and Liao royal families residing in Jin territory.[31] The execution of 130 members of the two royal clans in the span of a few months proved unpopular, and the Khitans soon revolted in Northeast China.[31] They refused to be drafted into the army, maintaining that conscription would leave their homeland unprotected from rival tribes on the steppes. Wanyan Liang rebuffed their demands. The Khitan rebels then killed several Jurchen officials. The rebellion was fragmented, and there were separate plans either to spread the revolt further by operating from Shangjing, the former Liao capital, or to move the Khitan people from Northeast China to Central Asia, where the Western Liao empire had formed after the demise of Liao.[28]

Regardless, Wanyan Liang was forced to divert resources and men away from the war effort to suppress the rebellion.[31]

Song preparations for Caishi

Diplomatic exchanges between the Song and Jin did not stop during the period preceding the war. The History of Song claims that the Song realized that the Jin were planning for an invasion when they noticed the discourtesy of one of the Jin diplomats.[31] Some Song officials foresaw the impending war,[31] but Emperor Gaozong hoped to maintain peaceful relations with the Jin. His reluctance to antagonize the Jin delayed the fortification of the Song border defenses. The Song quickly built just three military garrisons in 1161.[32] Wanyan Liang departed from Kaifeng on 1161 October 15.[31] The offensive comprised four armies, and Wanyan Liang personally led the army that entered Anhui.[32] The Jin passed the Huai River boundary on October 28, advancing into Song territory.[31] The Song resistance was minimal because they had fortified the southern shore of the Yangzi River and not the Huai.[31]

Chen Kangbo (陈康伯), prime minister (宰相) of the Song dynasty, commanded the Song navy and designed the anti-Jin offensive strategy. Yu Yunwen, a civil official, commanded the defending Song army. The paddle-wheel warships of the Song fleet, equipped with trebuchets that launched incendiary bombs made of gunpowder and lime, decisively defeated the light ships of the Jin navy.

Naval battle of Caishi

Wanyan Liang's army built its encampment near Yangzhou on the northern side of the Yangzi River.[2] The Jin advance had been slowed by Song victories in the west, where the Song captured several prefectures from the Jin. Wanyan Liang commanded his forces to cross the Yangzi at Caishi,[31] south of modern Nanjing.[33] A naval battle between Jin and Song took place on November 26 and 27, 1161.[31]

The Song strategy was planned by Chen Kangbo (陈康伯), prime minister and naval leader of the Song dynasty. Chen led a naval regiment of his own, dispatching general Yu Yunwen (a scholar-official), his lieutenants Dai Gao, Jian Kang, Shi Zhun, and others to lead the rest of the army.[33] Yu, who was a Drafting Official of the Secretariat (Chinese: 中書舍人; pinyin: zhongshu sheren), was at Caishi to distribute awards to Song soldiers who had been selected for their outstanding service. It was by chance that his visit coincided with Wanyan Liang's campaign.[34] When Yu first arrived, there were various scattered Song forces at Caishi, so Yu took command and built a cohesive unit.[35]

The Jin performed a ritual sacrifice of horses a day before the battle (animal sacrifice). On November 26, Jin troops embarked from the shore of the Yangzi and engaged the Song fleet.[33] Some of the ships they boarded were shoddily built.[36] The Jin had lost several ships in Liangshan, where they were bogged down by the shallow depths of Liangshan Lake as they were being transported to the Grand Canal.[30] Wanyan Liang had urgently requested the construction of more ships in 1161 to compensate for those still stuck in Liangshan.[37] One account of the war contends that the Jin ships were constructed in a week with materials recycled from destroyed buildings. The shortage of vessels and the poor quality of those available prevented the Jin from ferrying more soldiers needed for fighting a naval battle with the Song.[36]

The Song military response was stronger than Wanyan Liang had anticipated.[35] The paddle-wheel ships of the Song navy could move more rapidly and outmaneuver the slower Jin ships.[38] The Song kept their fleet hidden behind the island of Qibao Shan. The ships were to depart the island once a scout on horseback announced the approach of the Jin ships by signaling a concealed flag atop the island's peak. Once the flag became visible, the Song fleet commenced their attack from both sides of the island. Song soldiers operated traction trebuchets that launched incendiary "thunderclap bombs" and other soft-cased explosives containing lime and sulphur, which created a noxious explosion when the casing broke.[39] The Jin soldiers who managed to cross the river and reach the shore were assaulted by Song troops waiting on the other side.[34] The Song won a decisive victory.[2] Wanyan Liang was defeated again in a second engagement the next day.[34] After burning his remaining ships,[34] he retreated to Yangzhou, where he was assassinated before he could finish preparations for another crossing.[40]

One [the middle squadron] was stationed in midstream. These carried our elite troops to meet the attack. The remaining two squadrons were hidden in creeks to serve as reserve. Barely was the arrangement completed when suddenly we could hear the shouts of the Tatar hordes. The Tatar chieftain, holding a small red flag, ordered several hundred of his boats to cross the river. In a short time, seven boats reached the south bank. The Tatars leaped ashore and fought with the government troops. Your minister walk[ed] back and forth in our ranks, again and again exhorted our men about their great duty and also promising them rewards. Our men fought desperately, and after all the enemy [ashore] had been killed or taken prisoner, the battle continued on the river. Our large warships then attacked and sank many of the Tatar boats. Enemy troops who were drowned or killed are estimated to be as many as ten thousand. As darkness came, the sound of drums gradually quieted, and the Tatars fled in their remaining boats.[41]

— Yu Yunwen describing the battle at Caishi

Another account tells of General Chen Lugong (Chen Kangbo)「陈鲁公(陈康伯)采石」and how he also led naval regiments to defeat the Jin and defend the Song.

Casualties

Estimates for the number of soldiers and casualties at the battle vary widely. A Song source reports that there were 18,000 Song soldiers stationed in Caishi. One document claims that 400,000-600,000 Jin soldiers were present at the battle. Herbert Franke argues that the Song had only 120,000 soldiers fighting on the entire front[2] and that the half million figure could have referred to the number of soldiers that the Jin army had before crossing the Huai River toward the Yangzi. The desertions and casualties from suppressing revolts while advancing southward would have shrunk that number by the time the Jin reached the Yangzi.[34]

The History of Jin, a document written from the perspective of the Jin, reports Jin casualties between one meng'an (猛按 Jurchen unit of a thousand soldiers) and a hundred men, and two meng'an and two hundred men. The History of Song reports Jin casualties numbering four thousand soldiers and two commanders of wanhu (万户 ten thousand men) rank.[34] An account of the battle by a different Song source holds that 24,000 Jin soldiers died and that 500 combatants and five meng-an were taken as prisoners. A more conservative Song source estimates that the Jin only had 500 soldiers and 20 ships at Caishi.[35]

Military and naval technology

An account of the Song's technological capabilities is given in the Hai Qiu Fu (《海鳅赋》"Rhapsodic Ode on the Sea Eel Paddle Wheel Warships") by Yang Wanli:

The men inside them paddled fast on the treadmills, and the ships glided forwards as though they were flying, yet no one was visible on board. The enemy thought that they were made of paper. Then all of a sudden a thunderclap bomb was let off. It was made with paper (carton) and filled with lime and sulphur. (Launched from trebuchets) these thunderclap bombs came dropping down from the air, and upon meeting the water exploded with a noise like thunder, the sulphur bursting into flames. The carton case rebounded and broke, scattering the lime to form a smoky fog, which blinded the eyes of men and horses so that they could see nothing. Our ships then went forward to attack theirs, and their men and horses were all drowned, so that they were utterly defeated.[39][42]

There were up to 340 ships in the Song fleet during the battle of Caishi in 1161.[43] The Song fleet used trebuchets to bombard the Jin ships with incendiary bombs (pili huoqiu 霹雳火球 or huopao 霹雳火砲; "thunderclap fire balls") that contained a mixture of gunpowder, lime, scraps of iron, and a poison that was likely arsenic.[39] Reports that the bomb produced a loud sound suggests that the nitrate content of the gunpowder mixture was high enough to create an explosion.[44] The powdered lime in the bombs at Caishi generated a cloud of blinding smoke similar to tear gas.[45] The huoqiu released the smoke once the casing of the bomb shattered. Fuses activated the bombs after launching.[38]

The Jin conscripted thousands of blacksmiths to build the armor and weaponry of the fleet, and workers to dig out the canal necessary for transporting the ships from Tong to the Grand Canal through the northern port of Zhigu (直沽), modern Tianjin.[30] The Jin armored their light ships with thick rhinoceros hides. The ships had two stories; on the lower deck were the oarsmen responsible for rowing the ship, while soldiers on the upper deck could fire missile weapons.[38] Three different variations of the warships were constructed. Several of the ships became bogged down in Liangshan, and the ships built to replace them were of an inferior quality.[37] The Jin fleet were unable to defeat the larger and faster warships of the Song.[46]

The battle is significant in the technological history of the Song navy. The technological advances of the Song navy ensured its access to the East China Sea, where they competed with the military forces of Jin and Mongol rivals. Although huopao launched by the ship-mounted trebuchets had been invented decades earlier, the bombs did not become mandatory on Song warships until 1129. Paddle-wheel ships operated with treadmills were constructed continuously in various sizes between 1132 and 1183. The engineer Gao Xuan devised a ship outfitted with up to eleven paddle wheels on each side, and Qin Shifu, another engineer, designed the iron plating for armoring the ships in 1203. All these advances supported a rapid increase in the size of the force; according to Joseph Needham, "From a total of 11 squadrons and 3,000 men [the Song navy] rose in one century to 20 squadrons totalling 52,000 men".[43]

Aftermath

Traditional Chinese historiography celebrated the battle of Caishi as an important victory for the Song. Caishi was held in the same esteem as the Battle of Fei River in 383, when the Eastern Jin defeated the northern invaders of the Former Qin. It is portrayed as a victory against overwhelming odds, in which 18,000 Song soldiers overcame an army of nearly half a million men. Over the course of the battle, more and more Jin troops deserted in the face of the superior Song navy, thereby decreasing the total Jin force.[31]

The Song possessed multiple advantages. The Song had larger ships and ample time to prepare, while the Jin army gathered supplies and ships for the crossing. It was also impossible for the Jin to use cavalry, the most important asset of the Jurchen military, during a naval engagement.[2]

The battle was not solely responsible for devastating Wanyan Liang's military campaign. His own failings also led to his downfall.[2] Wanyan Liang's generals detested him, and his relationship with his men had deteriorated over the course of the war as the Jin were losing. There was a widespread disapproval of his reign in the empire, and Wanyan Liang's policies had alienated Jurchens, Khitans, and Han alike. Disaffected officers conspired to kill him, and he was assassinated on 1161 December 15. Emperor Shizong succeeded Wanyan Liang as ruler of the Jin. He had been enthroned weeks before the assassination, in a military coup that installed him as emperor while Wanyan Liang was absent from the court.[47] Shizong eventually rescinded many of Wanyan Liang's policies.[48]

The victory boosted the morale of the Song soldiers, improving confidence in the government and bolstering Song stability.[31][49] The Jin gave up their ambitions of pushing south and reunifying China under their rule.[49] The Jin army withdrew in 1162, and diplomatic relations between the two states resumed.[47]

Song Gaozong retired nine months after the conclusion of the battle.[36] The reasons for his abdication are complicated,[50] but Gaozong's handling of the war with Wanyan Liang may have had a part in his decision to resign.[51] He had ignored the warnings of a Jin attack,[52] and his hopes for conciliation held back plans for strengthening the Song defenses.[32]

Military clashes continued in Huainan and Sichuan, but Jin incursions after Caishi had no intent of reaching the Yangzi. The Jin had discovered that southern China's many lakes and rivers impeded their cavalry.[36] After losing the battle, they signed a peace treaty with the Song in 1165, ending hostilities. The Huai River border remained the same.[48]

See also

Notes

- 1 2 Lo 2012, p. 164.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Franke 1994, p. 242.

- ↑ Ebrey 2010, p. 136.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Holcombe 2011, p. 129.

- ↑ Franke 1994, p. 221.

- ↑ Mote 1999, p. 209.

- 1 2 3 Franke 1994, p. 225.

- ↑ Mote 1999, pp. 209–210.

- ↑ Mote 1999, p. 196.

- ↑ Franke 1994, pp. 227–229.

- ↑ Franke 1994, p. 229.

- ↑ Mote 1999, p. 292.

- ↑ Mote 1999, p. 293.

- ↑ Mote 1999, pp. 289–293.

- ↑ Tao 2009, p. 654.

- ↑ Mote 1999, p. 298.

- ↑ Tao 2009, p. 655.

- ↑ Franke 1994, p. 230.

- ↑ Franke 1994, pp. 230–232.

- ↑ Franke 1994, p. 232.

- ↑ Franke 1994, p. 233.

- ↑ Tao 2009, p. 684.

- ↑ Franke 1994, p. 235.

- ↑ Franke 1994, p. 239.

- ↑ Franke 1994, pp. 239–240.

- ↑ Tao 2002, p. 150.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Franke 1994, p. 240.

- 1 2 3 Mote 1999, p. 235.

- ↑ Franke 1994, pp. 240–241.

- 1 2 3 Chan 1992, p. 657.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 Franke 1994, p. 241.

- 1 2 3 Tao 2009, p. 704.

- 1 2 3 Tao 2002, p. 151.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Tao 2002, p. 152.

- 1 2 3 Tao 2009, p. 706.

- 1 2 3 4 Tao 2009, p. 707.

- 1 2 Chan 1992, pp. 657–658.

- 1 2 3 Turnbull 2002, p. 46.

- 1 2 3 Needham 1987, p. 166.

- ↑ Mote 1999, p. 233.

- ↑ Lo 2012, p. 165.

- ↑ Lo 2012, p. 167.

- 1 2 Needham 1971, p. 476.

- ↑ Needham 1987, pp. 166–167.

- ↑ Needham 1987, p. 165.

- ↑ Chan 1992, p. 658.

- 1 2 Franke 1994, p. 243.

- 1 2 Franke 1994, p. 244.

- 1 2 Tao 2002, p. 155.

- ↑ Tao 2009, pp. 707–709.

- ↑ Tao 2009, pp. 708–709.

- ↑ Tao 2009, p. 709.

References

- Chan, Hok-Lam (1992). "The Organization and Utilization of Labor Service Under The Jurchen Chin Dynasty". Harvard Journal of Asiatic Studies. 52 (2): 613–664. doi:10.2307/2719174. JSTOR 2719174.

- Ebrey, Patricia Buckley (2010) [1996]. The Cambridge Illustrated History of China (2nd ed.). Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-12433-1.

- Franke, Herbert (1994). "The Chin dynasty". In Twitchett, Dennis; Franke, Herbert (eds.). The Cambridge History of China, Volume 6: Alien Regimes and Border States, 907–1368. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. pp. 215–320. ISBN 978-0-521-24331-5.

- Holcombe, Charles (2011). A History of East Asia: From the Origins of Civilization to the Twenty-First Century. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-51595-5.

- Lo, Jung-pang (2012), China as a Sea Power 1127–1368

- Mote, Frederick W. (1999). Imperial China: 900–1800. Harvard University Press. ISBN 978-0-674-01212-7.

- Needham, Joseph (1971). Science and Civilisation in China: Civil Engineering and Nautics, Volume 4 Part 3. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-07060-7.

- Needham, Joseph (1987). Science and Civilisation in China: Military technology: The Gunpowder Epic, Volume 5, Part 7. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-30358-3.

- Tao, Jing-shen (2002). "A Tyrant on the Yangtze: The Battle of Ts'ai-shih in 1161". In Marie Chan; Chia-lin Pao Tao; Jing-shen Tao (eds.). Excursions in Chinese Culture: Festschrift in Honor of William R. Schultz. Chinese University Press. pp. 149–158. ISBN 978-962-201-915-7.

- Tao, Jing-shen (2009). "The Move to the South and the Reign of Kao-tsung". In Twitchett, Dennis; Smith, Paul Jakov (eds.). The Cambridge History of China, Volume 5: The Sung Dynasty and its Precursors, 907–1279, Part 1. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. pp. 556–643. ISBN 978-0-521-81248-1. (hardcover)

- Turnbull, Stephen (2002). Fighting Ships of the Far East: China and Southeast Asia 202 BC – AD 1419. Osprey Publishing. ISBN 978-1-78200-017-4.

Further reading

- Partington, J. R. (1960). A History of Greek Fire and Gunpowder. Johns Hopkins University Press. ISBN 978-0-8018-5954-0.