| Battle of Cape Rachado | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the Dutch–Portuguese War | |||||||

| |||||||

| |||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

|

| |||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

|

|

| ||||||

| Strength | |||||||

| 20 ships | 11 ships | ||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||

|

| ||||||

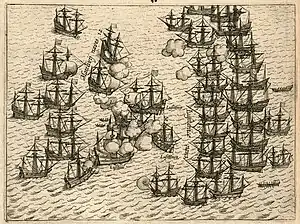

The Battle of Cape Rachado, off the present-day Malaccan exclave of Cape Rachado in 1606, was an important naval engagement between the Dutch East India Company and Portuguese fleets.

It marked the beginning of a conflict between the combined Dutch/Johor forces against the Portuguese. It was the biggest naval battle in the Malay Archipelago between two naval superpowers of the time with 31 ships (11 of the Dutch VOC and 20 of the Portuguese). Although the battle ended with a Portuguese victory, the ferocity of the battle itself and the losses sustained by the victor convinced the Sultanate of Johor to provide supplies, support, and later on much needed ground forces to the Dutch, forcing a Portuguese capitulation. 130 years of Portuguese supremacy in the region ended with the fall of the city and fortress of Malacca, almost 30 years later, in 1641.

Departure and alliance with Johor

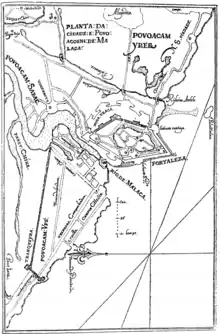

Malacca, which was earlier the capital of the Sultanate of Malacca, was besieged and wrested by the Portuguese in 1511, forcing the Sultan to retreat and found the successor state of Johor and continue the war from there. The port city, which the Portuguese had turned into a formidable fortress, was strategically situated in the middle of the strait of the same name giving control to both the spice trade of the Malay archipelago and supremacy over the sea lane of the lucrative trade between Europe and the Far East. The Dutch East Indies Company (VOC) decided that to expand further to the east, the Portuguese monopoly and especially Malacca must first be neutralised.

The fleet was the third sent by the VOC to the archipelago, with 11 ships – Oranje, Nassau, Middelburg, Witte Leeuw, Zwarte Leeuw, Mauritius, Grote Zon, Amsterdam, Kleine Zon, Erasmus, and Geuniveerde Provincien. The Oranje led with Admiral Cornelis Matelief de Jonge in command. The Dutch fleet set sail from Texel, Holland on 12 May 1605. The fleet departed with the sailors told that they were on a trade voyage as de Jonge was ordered to keep his true mission a secret, which was to besiege Malacca and force a Portuguese surrender.

They passed Malacca in April 1606 and arrived at Johor on 1 May 1606 where de Jonge proceeded to negotiate for a term of alliance with Johor. The pact was formally concluded on 17 May 1606 in which Johor had agreed to a combined effort with the Dutch to attempt to dislodge the Portuguese from Malacca. Unlike the Portuguese, the Dutch and Johor agreed to respect each other's religion, the Dutch would get to keep Malacca and the right to trade in Johor. The Dutch also would not attempt to interfere or wage war against Johor. In effect, the agreement served to limit Dutch influence on the Malay Peninsula in contrast to the islands of the archipelago which would become the Dutch East Indies.

Dutch fleet

| Name | Notes |

|---|---|

| Oranje | 700 tons, ship of Admiral Cornelis Matelief de Jonge, captained by Dirk Mol |

| Nassau | 320 tons, captained by Wouter Jacobz, sunk 18 August |

| Middelburg | 600 tons, captained by Simon Lambers, sunk 18 August |

| Witte Leeuw | 540 tons, captained by Claas Jansz |

| Zwarte Leeuw | 600 tons, captained by Abraham Mathijsz |

| Mauritius | 700 tons, captained by Gerrit Klaasz |

| Groote Zon | 540 tons, captained by Gerard Hendriksz |

| Amsterdam | 700 tons, ship of vice admiral Olivier de Vivere, captained by Reynier Lamberts |

| Kleine Zon | 220 tons, captained by Cornelis Jorisz |

| Erasmus | 500 tons, captained by Osier Cornelisz |

| Geuniveerde Provincien | 400 tons, captained by Antoine Antoniscz |

Portuguese fleet

| Name | Notes |

|---|---|

| Nossa Senhora da Conceição | 1000 tons, ship of Martim Afonso de Castro, captained by Manuel de Mascarenhas, burnt 31 October |

| São Simeão | 900 tons, captained by D. Francisco de Soto-mayor, burnt 25 October |

| São Salvador | 900 tons, captained by Álvaro de Carvalho, sunk 18 August |

| Nossa Senhora das Mercês | 900 tons, captained by Dom Henrique de Noronha |

| Todos os Santos | 800 tons, captained by D. Francisco de Noronha, burnt 22 October |

| São Nicolau | 800 tons, captained by D. Fernando de Mascarenhas, burnt 22 October |

| Santa Cruz | 600 tons, captained by Sebastião Soares, burnt 22 October |

| Dom Duarte de Guerra's galleon | 600 tons, captained by Dom Duarte de Guerra, sunk 18 August |

| António | 240 tons, captained by António Sousa Falcão, burnt 29 October |

Battle

Matelief de Jonge started the assault by besieging the fortress and city of Malacca. He was hoping that by blockading and cutting the supplies to the Portuguese, prolonged hunger and direct assault would force them to capitulate. However, this was not so, as their Johor allies were still unsure of the ability of the Dutch forces against Malacca and did not fully commit their resources to the attack, other than limited supplies and safe haven at their ports. The Dutch, with few soldiers, could not afford a land offensive against their well-entrenched opponent.

The Dutch maintained the siege for a time and the situation started to get worse for the Portuguese until 14 August 1606 when a Portuguese fleet from Goa arrived. Led by the Viceroy of Goa, Dom Martim Afonso de Castro, the siege was lifted when the 20-odd ships began to engage the VOC fleet off the Malaccan waters. The two fleets traded cannon fire and the Portuguese ships began to move northward, drawing the Dutch away from Malacca. On 16 August 1606, off the Portuguese lighthouse at Cape Rachado, the battle between the two fleets was enjoined.

Heavy cannon salvoes opened the battle with each side trying to weaken the opponent before the ships closed on each other and the battle would have to be fought hand-to-hand. After a couple of days of cannon duels, on the morning of 18 August, with the wind in favour of the Portuguese, Martim Afonso de Castro ordered the Portuguese to sail forth for the grapple. Matelief, seeing the danger, ordered his ships to turn sail away from the oncoming ships to evade boarding. But for some reason, the VOC ship Nassau failed to turn quickly, and ended up lingering behind, dangerously isolated. The Portuguese ship Santa Cruz dashed forth and boarded the Nassau.

Matelief de Jonge ordered his own ship, the Oranje, to quickly turn around to rescue the hapless Nassau, but the awkward manoeuvre sent the Oranje into a collision with the Middelburg. While the Dutch captains were busy disentangling their ships, Martim de Castro's ship, the Nossa Senhora da Conceicão, boarded the Nassau from the other side. The Dutch crew of the Nassau managed to jump into a lifeboat, leaving the fiercely burning Nassau behind.

In the meantime, another Portuguese ship, the São Salvador, drove towards the entangled VOC ships and pierced headlong into the Middelburg, but was immediately itself grappled by the Oranje from the side, which was in turn rammed from its open side by the ship of D. Henrique de Noronha (the Nossa Senhora das Mercês). The entangled duo had now become a quartet. A furious battle raged between the hopelessly entangled ships, with point-blank cannonades quickly setting the ships ablaze, as much a danger to one as the other.

Into this confusion entered the galleon of Dom Duarte de Guerra, who sought to toss a line to help tow Noronha's ship away from the burning Oranje. But the winds were unfavorable and instead the rescuer found itself drifting straight across the bows of the entangled ships. Just then the Mauritius decided to join the fight and pierced Dom Duarte de Guerra's ship from the other side. The battle had reached its height in the sextet of burning, interlocked ships.

Matelief de Jonge realized that the smaller Dutch ships wouldn't last long, and that they must get out of this position before the larger Portuguese drop anchor. He ordered the Oranje to cut the grapple-lines' to the São Salvador, and sailed away from the mess. Albeit, Noronha's Mercês was still tied to Oranje and was dragged along with it. The Mauritius also decided to cut its grappling cables when it noticed Dom Duarte de Guerra's galleon had caught fire.

The remaining entangled ships—the Middelburg, the São Salvador, and Dom Duarte de Guerra's galleon—would burn and go down together, still entangled.

In the meantime, a furious fight continued to be fought between Matelief's Oranje and Noronha's Mercês, who were still grappled. But at length Matelief proposed a truce to D. Henrique de Noronha, to allow them to put out their fires and save their ships. Noronha agreed. But the Oranje had dropped anchor, and as the crews went about extinguishing the flames, the winds were now sending the remaining Dutch ships towards the Oranje and the Portuguese ships away from it. Noronha's fate seemed doomed, but Matelief, not wishing to exploit a truce he had himself proposed, magnanimously offered to cut the grapple and allow Noronha to slip away unmolested back to the Portuguese line. For this honourable gesture, Noronha swore never to personally fight Matelief again.

This final gentlemanly exchange displeased the vice-roy Martim Afonso de Castro, who would have preferred to allow Noronha's ship to continue burning and take the Dutch flagship down with it. D. Henrique de Noronha was promptly dismissed from the command of the Mercês, and replaced by another.

Matelief de Jonge deemed that the losses suffered were too much and ordered the Dutch fleet to disengage and abandoned the fight. The battle was won by the Portuguese, but the failed Dutch attack marked the beginning of a serious threat to their dominance in the archipelago, which culminated in a massive Dutch-Johor-Aceh assault 30 years after which managed to capture Malacca.

Aftermath

The Dutch requested shelter from Johor and arrived at the Johor River on 19 August 1606. Overall the Dutch lost Nassau and Middelburg. 150 Dutch were killed and more wounded, Johor allied losses amounted to several hundred. The Portuguese lost São Salvador and Dom Duarte de Guerra's smaller galleon while suffering 500 deaths (Portuguese and allies). The battle also proved the tenacity of the Dutch in their war against the Portuguese, which caused the Sultan of Johor to fully commit on providing the much needed armies and additional ships and resources. The Portuguese victory came to naught when the Dutch, having repaired their ships, returned to Malacca 2 months later to find the Portuguese fleet having left, leaving only 10 ships behind. The Dutch subsequently sank all 10 ships.

Shipwrecks and excavation

All four ships lost at Cape Rachado were found by Gerald Caba of CABACO Marine Pte Ltd, Singapore. Then they were recovered in 1995 under the supervision of Mensun Bound from Oxford University. Nassau had been found about 8-nautical-mile (15 km) off the modern town of Port Dickson, Negeri Sembilan. The wreck was found with 15 cannons, cannonballs, ropes and wooden barrels with animal bones, coins and a Chinese jar. The wreckage of Middelburg, São Salvador and Dom Duarte de Guerra's galleon was found 0.7-nautical-mile (1.3 km) away from Nassau.

Some of the retrieved artefacts from Nassau are on display at the Lukut Museum in the town of Port Dickson.

Mauritius left the Strait of Malacca on 27 December 1607 and sank on 19 March 1609 off the Cape Lopes Gonçalves, Gabon. The wreckage was found in 1985. Witte Leeuw met her doom off the shores of St. Helena when she and three other VOC ships surprised two Portuguese caravels anchored in the bay. As they approached, the Portuguese recovered and started a cannonade that sent the Witte Leeuw to the bottom of the sea with all hands on board. When salvaged in 1976/8, it was found to be carrying a substantial amount of porcelain (200-400 kg now in shards), mainly Chinese export B&W known as kraak with only 290 intact pieces.[1] Another VOC ship managed to escape severely damaged but sank a few days later.

References

- ↑ The Ceramic Load of the 'Witte Leeuw' 1613 (Amsterdam: The Rijksmuseum, 1982)

- Borschberg, Peter (2016). Admiral Matelieff's Singapore and Johor, 1606-1616. Singapore: NUS Press. ISBN 9789814722186.

- Borschberg, Peter (2015). Journal, Memorials and Letters of Cornelis Matelieff de Jonge. Singapore: NUS Press. ISBN 9789971697983.

- Borschberg, Peter (2011). Hugo Grotius, the Portuguese and Free Trade in the East Indies. Singapore: NUS Press. ISBN 9789971694678.

- De Witt, Dennis (2007). History of the Dutch in Malaysia. Malaysia: Nutmeg Publishing. ISBN 9789834351908.