| Battle of Dinwiddie Court House | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the American Civil War | |||||||

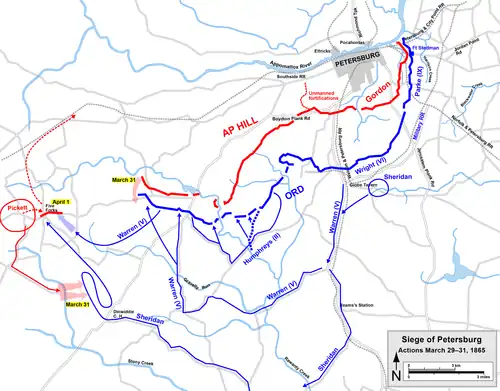

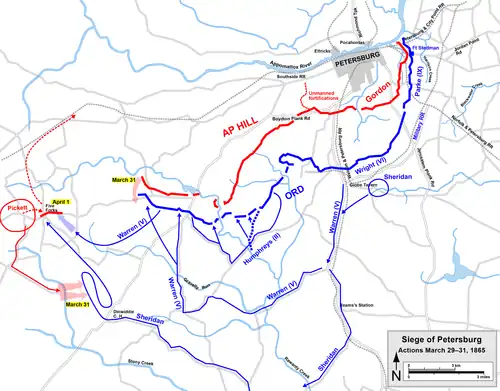

Map of the Siege of Petersburg of the American Civil War, actions March 29–31, 1865 | |||||||

| |||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

|

|

| ||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

| Philip H. Sheridan |

George E. Pickett Fitzhugh Lee | ||||||

| Strength | |||||||

| 9,000[1] | 10,600[2] | ||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||

| 354[3] | 760[3] | ||||||

The Battle of Dinwiddie Court House was fought on March 31, 1865, during the American Civil War at the end of the Richmond-Petersburg Campaign and in the beginning stage of the Appomattox Campaign. Along with the Battle of White Oak Road which was fought simultaneously on March 31, the battle involved the last offensive action by General Robert E. Lee's Confederate Army of Northern Virginia attempting to stop the progress of Lieutenant General Ulysses S. Grant's Union Army (Army of the Potomac, Army of the Shenandoah and Army of the James). Grant's forces were moving to cut the remaining Confederate supply lines and to force the Confederates to extend their defensive lines at Petersburg, Virginia and Richmond, Virginia to the breaking point, if not to force them into a decisive open field battle.[4]

On March 29, 1865, a large Union cavalry force of between approximately 9,000 and 12,000 troopers[5] moved toward Dinwiddie Court House, Virginia about 4 miles (6.4 km) west of the end of the Confederate lines and about 5 miles (8.0 km) south of the important road junction at Five Forks, Virginia. Under the command of Major General Philip Sheridan, and still designated the Army of the Shenandoah, the Union force consisted of the First Division under Brigadier General Thomas Devin and the Third Division of Brigadier General (Brevet Major General) George Armstrong Custer under the overall command of Brigadier General (Brevet Major General) Wesley Merritt as an unofficial corps commander, and the Second Division, detached from the Army of the Potomac, commanded by Major General George Crook. Five Forks was a key location for control of the critical Confederate supply line of the South Side Railroad (sometimes shown as Southside Railroad). While Devin's and Crook's divisions reached Dinwiddie Court House in the late afternoon of March 29, Custer's division was protecting the bogged down wagon train about 7 miles (11 km) behind the other two divisions.

Also on March 29, 1865, the Union V Corps under Major General Gouverneur K. Warren moved to the end of the Confederate White Oak Road Line, the far right flank of the Confederate defenses. Warren's corps seized control of advance Confederate picket or outpost positions and occupied a segment of a key transportation and communication route, the Boydton Plank Road, at the junction of the Quaker Road, as a result of the Battle of Lewis's Farm. After a day of pushing the Union line forward on March 30, Warren's force was driven back temporarily on March 31 by a surprise Confederate attack. The V Corps rallied and regained their position on the Boydton Plank Road, cutting direct communication over the White Oak Road between the Confederate defensive line and Major General George Pickett's task force about 4 miles (6.4 km) west at Five Forks, during the afternoon of March 31 at the Battle of White Oak Road. At the end of the day, the V Corps remained the closest Union infantry corps to Sheridan's position.

At the same time on March 31, Sheridan's cavalry force deployed north from Dinwiddie Court House in a movement aimed at occupying Five Forks. Sheridan was thrown on the defensive by an attack by both Confederate infantry and cavalry under Major General George Pickett and Major General Fitzhugh Lee. Sheridan's men gave way at various locations during the day but fought long and hard delaying actions, keeping their organization after withdrawals and inflicting hundreds of casualties on the Confederates. Finally reinforced by Custer with two brigades of his division under Colonels Alexander C. M. Pennington, Jr. and Henry Capehart which were brought forward from wagon train guard duty, the Union cavalry divisions at Dinwiddie Court House held their line just north of the town. Sheridan's force appeared to be in peril by nightfall due to the threatening position of the strong Confederate force just outside the village. During the night of March 31, however, Brigadier General Joseph J. Bartlett's brigade of Brigadier General (Brevet Major General) Charles Griffin's First Division of the V Corps, followed hours later by Warren's entire corps, maneuvered Pickett back to Five Forks by advancing on his flank before he could take advantage of his advanced position the next day. By 7:00 a.m., Sheridan had a corps of infantry as well as his cavalry to proceed against Five Forks.

The battles at White Oak Road and Dinwiddie Court House, while initially successful for the Confederates, and even yielding a tactical victory at the end of the day at Dinwiddie,[6] ultimately did not advance the Confederate position or achieve their strategic objective of weakening and driving back the Union forces or separating Sheridan's force from support. The Confederates suffered at least 1,560 casualties to their dwindling forces in the two battles. The battles of March 31 and the troop movements in their aftermath set the stage for the Confederate defeats and the collapse of Confederate defensive lines at the Battle of Five Forks on the following day, April 1, 1865, and at the Third Battle of Petersburg (also known as the Breakthrough at Petersburg) on April 2, 1865. The evacuation of Petersburg and Richmond on the night of April 2–3 and march west of the Confederate Army, with the Union Army in close pursuit, ultimately led to the surrender of Lee's Army of Northern Virginia after the Battle of Appomattox Court House, Virginia on April 9, 1865.

Background

Military situation

Siege of Petersburg

During the 292-day Richmond–Petersburg Campaign (Siege of Petersburg) Union General-in-Chief Ulysses S. Grant had to conduct a campaign of trench warfare and attrition in which the Union forces tried to wear down the less numerous Confederate Army of Northern Virginia, destroy or cut off sources of supply and supply lines to Petersburg and Richmond and extend the defensive lines which the outnumbered and declining Confederate force had to defend to the breaking point.[7][8][9] After the Battle of Hatcher's Run on February 5–7, 1865 extended the armies' lines another 4 miles (6.4 km), Lee had few reserves after manning the lengthened Confederate defenses.[10] Lee knew he must soon move part or all of his army from the Richmond and Petersburg lines, obtain food and supplies at Danville, Virginia or possibly Lynchburg, Virginia and join General Joseph E. Johnston's force opposing Major General William T. Sherman's army in North Carolina. Lee thought that if the Confederates could quickly defeat Sherman, they might turn back to oppose Grant before he could combine his forces with Sherman's.[11][12][13][14] Lee began preparations for the army's movement and informed Confederate President Jefferson Davis and Confederate States Secretary of War John C. Breckinridge of his evaluation and plan.[15][16][17]

Lee was aware that Sherman's army moving through North Carolina might combine with Grant's army at Petersburg if Johnston's army could not stop Sherman and that his own declining army could not hold the Richmond and Petersburg defenses much longer. In support of his plan to hold off Grant as long as possible and then gain at least a time advantage in his planned move, during March 1865, Lee considered and finally accepted a plan by Major General John Brown Gordon to launch an attack on Union Fort Stedman. The objective would be to break the Union lines east of Petersburg, or at least to compel the Union forces to shorten their lines by gaining significant ground in a substantial and damaging attack. This was expected to permit Lee to shorten his lines and send a large force to help Johnston, or if necessary give the Confederates a head start in evacuating Richmond and Petersburg and combining Lee's entire force with Johnston's dwindling army.[18][19][20]

Gordon's surprise attack on Fort Stedman in the pre-dawn hours of March 25, 1865 ultimately failed with the Confederates suffering about 4,000 casualties, including about 1,000 captured, which the Confederates could ill afford.[18][21] The Union Army lost no ground due to the attack and their casualties were too few to deter them from further, immediate action.[22][23] In response to the Confederate attack on Fort Stedman in the afternoon of March 25, at the Battle of Jones's Farm, Union forces of the II Corps and the VI Corps captured Confederate picket lines near Armstrong's Mill and extended the left end of the Union line about 0.25 miles (0.40 km) closer to the Confederate fortifications. This put the VI Corps within easy striking distance, about 0.5 miles (0.80 km), of the Confederate line.[24][25] After the Confederate defeats at Fort Stedman and Jones's Farm, Lee knew that Grant would soon move against the only remaining Confederate supply lines to Petersburg, the South Side Railroad and the Boydton Plank Road, which also might cut off all routes of retreat from Richmond and Petersburg.[26][27][28]

March 29 orders and movements

Grant's orders

On March 24, 1865, the day before the Confederate attack on Fort Stedman, Grant already had planned an offensive for March 29, 1865.[29] The objective was to draw the Confederates out into an open battle where they might be defeated and their military effectiveness destroyed. In the alternative, if the Confederates held their lines, the Union force could cut the remaining road and railroad supply and communication routes, the South Side Railroad and the Boydton Plank Road, which connected with the previously severed Weldon Railroad to Petersburg, and the Richmond and Danville Railroad to Richmond, and to stretch Lee's line to the breaking point.[30][31][32]

Grant ordered Major General Edward Ord to move part of his Army of the James from the lines near Richmond to fill in the lines to be vacated by the II Corps commanded by Major General Andrew A. Humphreys at the southwest end of the Petersburg line before II Corps moved to the west. Ord moved two divisions of Major General John Gibbon's XXIV Corps under Brigadier Generals Charles Devens and William Birney and one division of XXV Corps under Brigadier General John W. Turner to take over lines on the south side of the Appomattox River.[33] This freed two corps of Major General George Meade's Army of the Potomac for offensive action against Lee's flank and railroad supply lines: Major General Humphrey's II Corps and Major General Warren's V Corps.[30][31][34] Grant ordered these corps, along with Major General Philip Sheridan's cavalry (First Division of Brigadier General Thomas Devin and the Third Division of Brigadier General (Brevet Major General) George Armstrong Custer but both under the overall command of Brigadier General (Brevet Major General) Wesley Merritt as an unofficial corps commander and the Second Division of Major General George Crook detached from the Army of the Potomac), still designated the Army of the Shenandoah, to move west, with the cavalry first taking control of Dinwiddie Court House and severing the Boydton Plank Road at that location.

Lee's orders

Lee, who was already concerned about the ability of his weakening army to maintain the defense of Petersburg and Richmond, realized that the defeat at Fort Stedman would encourage Grant to make a move against his supply lines and right flank. Lee already had prepared to send some reinforcements to his right flank, the southwestern end of his line. Early in the day on March 29, Lee sent Major General George Pickett with three of his brigades commanded by Brigadier Generals William R. Terry, Montgomery Corse and George H. Steuart via the deteriorated South Side Railroad to Sutherland Station.[35] The trains shuttling the troops to Sutherland Station were so slow that it was late night before the last of Pickett's men reached their destination, 10 miles (16 km) west of Petersburg.[36][37] From Sutherland Station, Pickett moved south on Claiborne Road to White Oak Road and Burgess Mill,[2] near the end of the Confederate line. There he added the two brigades of Brigadier Generals Matt Ransom and William Henry Wallace from Major General Bushrod Johnson's division,[38] along with a six-gun battery under Colonel William Pegram to deploy to Five Forks with his three brigades.[38]

Battle of Lewis's Farm

On March 29, 1865, Warren's corps led by the First Brigade of Brigadier General (Brevet Major General) Charles Griffin's First Division under the command of Brigadier General Joshua Chamberlain proceeded up the Quaker Road toward its intersection with the Boydton Plank Road and the Confederates' nearby White Oak Road Line.[27][39][40] The move resulted in an engagement at the Battle of Lewis's Farm of Confederate brigades of Brigadier Generals Henry A. Wise, William Henry Wallace and Young Marshall Moody from the division of Major General Bushrod Johnson, corps of Lieutenant General Richard H. Anderson, and Union troops of Griffin's First Division of the V Corps.[41][42]

North along Quaker Road, across Rowanty Creek at the Lewis Farm, Chamberlain's men encountered Johnson's force. A back-and-forth battle ensued during which Chamberlain was wounded and almost captured. Chamberlain's brigade, reinforced by a four-gun artillery battery and regiments from the brigades of Colonel (Brevet Brigadier General) Edgar M. Gregory and Colonel (Brevet Brigadier General) Alfred L. Pearson, who was later awarded the Medal of Honor, drove the Confederates back to their White Oak Road Line. Casualties for both sides were nearly even at 381 for the Union and 371 for the Confederates.[43][44][45][46][47] After the battle, Griffin's division moved up to and occupied the junction of the Quaker Road and Boydton Plank Road near the end of the Confederate White Oak Road Line.[48]

Encouraged by the Confederate failure to press their attack at Lewis's Farm and their withdrawal to their White Oak Road Line, Grant decided to expand Sheridan's mission to a major offensive rather than just a railroad raid and forced extension of the Confederate line or a battle only if offered.[48][49]

Sheridan's movement

At about 5:00 p.m., on March 29, 1865, two divisions of Sheridan's force commanded by Crook and Devin entered Dinwiddie Court House without opposition.[27][50] Sheridan posted pickets at the roads entering the town for protection from Confederate patrols.[27] Sheridan's third division commanded by Custer was 7 miles (11 km) behind Sheridan's main force protecting the bogged down wagon trains.[27][51] At Dinwiddie Court House, Sheridan's cavalry was positioned to occupy the crucial road junction at Five Forks in Dinwiddie County, about 5 miles (8.0 km) to the north, to which Lee was just sending defenders, and then to attack the two remaining Confederate railroad connections to Petersburg and Richmond.[44][49][52]

March 30 orders and movements

Lee's orders and Confederate movements

General Lee perceived the threat from the Union moves on March 29 and thinned his lines to strengthen the defenses on his far right. He also finalized organization of a Confederate mobile force under Major General George Pickett with cavalry help from Major General Fitzhugh Lee to protect the key road junction of Five Forks. Lee wanted to control this intersection in order to keep open the South Side Railroad and important roads and to drive the Union force back from its advanced position at Dinwiddie Court House. A steady, heavy rain started on the afternoon of March 29 and continued through March 30, slowing movements and limiting actions.[27][53]

Although Fitzhugh Lee's cavalry division passed through Petersburg and reached Sutherland Station about the time Sheridan reached Dinwiddie Court House on March 29, Major General Thomas L. Rosser's and Major General W.H.F. "Rooney" Lee's divisions had to detour around Sheridan's force in their moves from positions at Spencer's Mill on the Nottoway River and Stony Creek Station[54] and did not arrive at Sutherland Station until March 30.[51] At Sutherland Station earlier that day, General Lee verbally told Major General Fitzhugh Lee to take command of the cavalry and to attack Sheridan at Dinwiddie Court House.[55] When Rosser and Rooney Lee's divisions arrived at Five Forks on the night of March 30, Fitzhugh Lee took overall command of the cavalry and put Colonel Thomas T. Munford in command of his own division.[56]

Earlier on March 30, a day of steady torrential rain, General Lee met with several officers including Anderson, Pickett and Heth at Sutherland Station.[2] From there, Lee ordered Pickett to move his force about 4 miles (6.4 km) west along White Oak Road to Five Forks.[38] Lee instructed Pickett to join with Fitzhugh Lee's cavalry and attack Sheridan at Dinwiddie Court House with the objective of driving Sheridan's force further away from the Confederate supply lines.[2] With the 4 miles (6.4 km) gap between the end of the Confederate White Oak Road Line southwest of Petersburg and Pickett's force at Five Forks in mind, on March 30, Lee made additional deployments to strengthen his right flank.[57][58]

Skirmishing with and reacting to feints from Union patrols of the 6th Pennsylvania Cavalry under Colonel Charles L. Leiper delayed Pickett's force from reaching Five Forks until 4:30 p.m.[59] When Pickett reached Five Forks where Fitzhugh Lee's cavalry was waiting, he conferred with Fitz Lee about whether to proceed toward Dinwiddie Court House then. After discussing the situation, Pickett decided because of the late hour and the absence of the other cavalry divisions to wait until morning to move his tired men against Sheridan at Dinwiddie Court House.[56] Pickett did send William R. Terry's and Montgomery Corse's brigades to an advanced position south of Five Forks to guard against surprise attack.[53] Some of Union Brigadier General Thomas Devin's men skirmished with the advanced infantry brigades before the Confederates were able to settle into their positions.[56] By 9:45 p.m., Pickett's force was deployed along the White Oak Road.[38]

Union orders and movements; March 30 skirmish

Before Pickett's infantry arrived at Five Forks on March 30, Union cavalry patrols from Brigadier General Thomas Devin's division approached the Confederate line along White Oak Road at Five Forks and skirmished with Fitzhugh Lee's cavalry division.[37][53][59] As they approached Five Forks, a patrol of the 6th United States Cavalry Regiment under Major Robert M. Morris encountered Fitzhugh Lee's troopers and lost 3 officers and 20 men in the encounter.[60] The Confederates also suffered some casualties, including Brigadier General William H. F. Payne who was wounded.[60]

As the rain continued on March 30, Grant sent a note to Sheridan in which he said that cavalry operations seemed to be impossible and perhaps he should leave enough men to hold his position and return to Humphreys' Station for forage.[61] He even suggested going by way of Stony Creek Station to destroy or capture Confederate supplies there.[61] Sheridan responded by going to Grant's headquarters which had been moved forward to near the Vaughan Road crossing of Gravelly Run on the night of March 30 to urge him to press ahead regardless of the weather and road conditions.[49][62] Sheridan supported his argument by the false statement that his men had already reached White Oak Road at Five Forks.[63] In fact, Devin's men had been driven back from Five Forks and had encamped about a mile away at the John Boisseau house.[64] During their discussions, Grant told Sheridan he would send him the V Corps for infantry support and that his new orders were not to extend the line further but to turn the Confederate flank and to break Lee's army.[65] Sheridan wanted the VI Corps which had fought with him in the Shenandoah Valley.[66] Grant again told him that the VI Corps was too far from his position to make the move.[67]

Battle of White Oak Road

On the morning of March 31, General Lee inspected his White Oak Road Line and learned that the Union left flank held by Brigadier General Romeyn B. Ayres's division had moved forward the previous day and was "in the air." A wide gap also existed between the Union infantry and Sheridan's nearest cavalry units near Dinwiddie Court House.[68][69] Lee ordered Major General Bushrod Johnson to have his remaining brigades under Brigadier General Henry A. Wise and Colonel Martin L. Stansel in lieu of the ill Young Marshall Moody,[68][70][71] reinforced by the brigades of Brigadier Generals Samuel McGowan and Eppa Hunton, attack the exposed Union line.[68][70]

Stansel's, McGowan's and Hunton's brigades attacked both most of Ayres's division and all of Brigadier General (Brevet Major General) Samuel Crawford's division which quickly joined the fight as it erupted.[72][73] Two Union divisions of over 5,000 men were thrown back by three Confederate brigades.[74] Brigadier General (Brevet Major General) Charles Griffin's division and the V Corps artillery under Colonel (Brevet Brigadier General) Charles S. Wainwright finally stopped the Confederate advance short of crossing Gravelly Run.[72][73][74][75] Adjacent to the V Corps, Major General Andrew A. Humphreys conducted diversionary demonstrations and sent two of Brigadier General Nelson Miles's brigades from his II Corps forward and they initially surprised and after a sharp fight drove back Wise's brigade on the left of the Confederate line, taking about 100 prisoners.[72][73][76]

At 2:30 p.m., Brigadier General Joshua Chamberlain's men forded the cold, swollen Gravelly Run, followed by the rest of Griffin's division and then the rest of Warren's reorganized units.[77][78][79] Under heavy fire, Chamberlain's brigade, along with Colonel (Brevet Brigadier General) Edgar M. Gregory's, charged Hunton's brigade and drove them back to the White Oak Road Line.[73][79] Then Chamberlain's and Gregory's men crossed White Oak Road.[80] The remainder of the Confederate force then had to withdraw to prevent being outflanked and overwhelmed.[79] Warren's corps ended the battle across White Oak Road between the end of the main Confederate line and Pickett's force at Five Forks, cutting direct communications between Anderson's (Johnson's) and Pickett's forces.[73][79][81] Union casualties (killed, wounded, missing – presumably mostly captured) were 1,407 from the Fifth Corps and 461 from the Second Corps and Confederate casualties have been estimated at about 800.[82][83]

While Warren's V Corps led by Griffin's division, with help from Miles's division of Humphrey's II Corps, turned the Battle of White Oak Road into a Union victory, Sheridan was hard pressed as the Battle of Dinwiddie Court House ended for the day.[84]

Morning conditions; troop dispositions

Early on March 31, 1865, Union Major General Philip Sheridan told Lieutenant General Ulysses S. Grant that he believed he could turn the Confederate right or make a breakthrough if the rain stopped and he had the help of an infantry corps. Sheridan wanted the VI Corps commanded by Major General Horatio G. Wright, which he had worked with in the Shenandoah Valley Campaigns of 1864, not the V Corps under Major General Gouverneur Warren whom Sheridan did not trust.[85][86] Grant replied a few hours later that the VI Corps was in the center of the line and too far away to support Sheridan but he could move the II Corps by the next day.[87] Grant also said that Wright thought he could go through the line from his current position.[84][87] Although heavy rain continued that day, Confederate Major General George E. Pickett was about to change the situation and options of the Union commanders.[87]

At 9:00 a.m., Brigadier General (Brevet Major General) Wesley Merritt reinforced the Union picket line and ordered Brigadier General Thomas Devin to send out strong combat patrols from his camp at J. Boisseau's farm north of Dinwiddie Court House to scout Confederate positions covering White Oak Road[84][87][88] Patrols moving up Crump Road and Dinwiddie Court House Road attracted Confederate rifle fire near White Oak Road.[84][87][88]

Brigadier General Henry E. Davies's brigade of Major General George Crook's division also was at J. Boisseau's farm.[89][90] Patrols from Davies's brigade were sent to watch the area on the east of a swampy creek called Chamberlain's Bed.[84][88][89] Sheridan was mindful of the possibility that his force could come under attack from the west because he had blocked Confederate Major Generals W.H.F. "Rooney" Lee's and Thomas L.Rosser's approach from the south the previous day.[84] Soon after Davies's patrol reached their station, his men spotted both Confederate cavalry and infantry heading toward Dinwiddie Court House on the west side of the creek.[91] Pickett had decided to march south from Five Forks on Scott Road at about 9:00 a.m. for an attack on Sheridan at Dinwiddie Court House despite the bad weather and the hunger of his ill-fed troops.[92]

When Sheridan heard about the movement, he assumed the Confederates were moving on Scott Road west of the creek.[93] Davies's brigade was sent to cover the creek's northern crossing at Danse's Ford.[93] Colonel (Brevet Brigadier General) Charles H. Smith's brigade was set to hold the Ford Station Road crossing at Fitzgerald's Ford, about 1 mile (1.6 km) south of Danse's Ford.[93] Colonel (Brevet Brigadier General) J. Irvin Gregg's brigade stood in reserve at the junction of Adams and Brooks roads, midway between the two crossings.[92] While these brigades faced west, Colonel Charles L. Fitzhugh's brigade was on the right on Dinwiddie Road and Colonel Peter Stagg's brigade was on Crump Road, where they could cover the other brigades as well as the roads from the north.[92]

Opposing forces

Union

Confederate

Battle

Fitzhugh Lee's attack at Fitzgerald's Ford

At about 11:00 a.m., Fitzhugh Lee's lead brigade, Brigadier General Rufus Barringer's North Carolina brigade from Rooney Lee's division, reached Fitzgerald's Ford, the southern ford of Chamberlain's Bed and the closer ford to Dinwiddie Court House.[94] The North Carolina troopers were held back by a dismounted detachment of the 2nd Regiment New York Mounted Rifles with their repeating carbines.[95] The 6th Ohio Cavalry joined the fight, also with repeating carbines.[94][95] Smith deployed a battalion of the 1st Maine Volunteer Cavalry Regiment across the creek but were forced back by a large Confederate battle line.[94][96] The Confederates were able to fight their way across the creek, with the 5th North Carolina Cavalry crossing under heavy fire, the 1st North Carolina Cavalry crossing upstream and the 2nd North Carolina Cavalry crossing behind a mounted battalion of the 13th Virginia Cavalry. Colonel Smith moved up the remainder of the 1st Maine Cavalry from 1 mile (1.6 km) down the road and the 13th Ohio Cavalry.[95][97] With the 1st Maine Cavalry on the top of a hill and the 6th Ohio Cavalry in the woods to their left, Smith's Union force drove back the 13th Virginia Cavalry, who in turn forced the 2nd North Carolina Cavalry into deep water in the ford. The 1st North Carolina Cavalry was driven back across the creek by the 2nd New York Mounted Rifles.[94][96] Barringer's brigade lost a large number of officers as it retreated across the creek and the Union brigade took as prisoners the Confederates who stayed on the east side.[97]

Then, after 11:00 a.m., Pickett reached Fitzgerald's Ford as Rooney Lee's failing attack ground to a stop.[98] Pickett decided to go back north for 1 mile (1.6 km) to cross at Danse's Ford with his three infantry brigades (Corse's, Terry's and Steuart's) and Rosser's cavalry.[91] Pickett's plan was for Ransom's two infantry brigades (Ransom's and William Henry Wallace's) to cross at Fitzgerald's Ford with Fitz Lee and Rooney Lee.[98]

At about 2:30 p.m., Sheridan sent a report to Grant that his men had held back the Confederates at Fitzgerald's Ford and would now attack them.[98] He also erroneously reported that Confederate Major General Robert F. Hoke's infantry division was up from North Carolina and that Devin's division was in contact with the line of the Confederate infantry outposts at Five Forks.[99] In fact, Pickett's infantry was about to force their way across Chamberlain's Bed at Danse's Ford. Devin's patrols actually had spotted only Colonel Thomas T. Munford's cavalry division near Five Forks. Rooney Lee was preparing another attack on the Fitzgerald Ford of Chamberlain's Bed for the afternoon.[99]

At Fitzgerald's Ford, the 2nd North Carolina Cavalry, supported by the 5th North Carolina Cavalry, were thrown back as the 5th North Carolina had been in the morning.[99] Only the 1st North Carolina Cavalry could keep a foothold across the ford. Rooney Lee ordered Brigadier General Richard L. T. Beale's Virginia cavalry brigade to attack across the creek and come in from the left. Both Beale's and Barringer's cavalry brigades now rushed across Smith's line, forcing the Union force to retreat into an open field and quickly withdraw.[99]

Pickett's attack at and crossing of Danse's Ford

After he was advised of the collapse of Smith's line in the late morning, Crook ordered Davies who was not under attack, to help Smith.[100] Davies left a battalion under Major Walter W. Robbins to guard Danse's Ford and started his men on foot along a narrow, muddy road toward Fitzgerald's Ford. Davies rode ahead and discovered that Smith had stabilized the situation, throwing those troopers of Barringer's brigade who had managed to cross the creek back across it.[100] Davies then turned his men back on the double because of the sound of heavy firing near Danse's Ford.[100] Soon after Davies had left for Fitzgerald's Ford, Robbins's battalion came under attack by Brigadier General Montgomery Corse's infantry brigade. Robbins held a strong position with protection from breastworks. Corse sent patrols to ford the creek and attack Robbins from the flanks.[100] Corse's men pushed back men from Major James H. Hart's New Jersey battalion who were guarding the left flank. Outflanked and outnumbered, Robbins's men began to flee when Davies's tired troopers came up.[97] The 10th Regiment New York Volunteer Cavalry held the line for a few volleys and then fled, almost losing their held horses in the process.[101]

Union delaying actions

Pickett then sent the other infantry brigades across the ford.[97][101] Davies fell back toward Adams Road with Colonel Hugh R. Janeway covering the retreat with his 1st and 2nd battalions of the 1st New Jersey Volunteer Cavalry.[97][101] They were soon supported by a Michigan regiment from Colonel Stagg's brigade, sent by Brigadier General Devin when Janeway requested support.[101]

Until 2:00 p.m., Munford's patrols had kept Devin's patrols busy on Dinwiddie Court House Road near White Oak Road.[102] Devin did not know that Pickett had moved across the ford but withdrew Fitzhugh's brigade to the junction of Dinwiddie and Gravelly Run Church roads when he learned that Five Forks was held by Pickett's infantry and at least a division of cavalry.[103] Devin accompanied Stagg's men to discover the situation.[97] Upon seeing Davies's brigade in retreat, Devin tried unsuccessfully to rally them.[91][103] Then he sent an order to Colonel Fitzhugh to move to the road from Danse's ford, leaving one regiment on the Dinwiddie Road.[97][103] After struggling through Davies's stragglers, Fitzhugh's men relieved Janeway's rear guard and stopped Corse's advance.[104] Davies took his men to J. Boisseau's farm to be reorganized, losing dozens of men along the way, including Major James H. Hart of the 1st New Jersey Cavalry.[104][105]

Staggs, Fitzhugh, Davies withdraw

Munford then committed his cavalry division to advance down the Dinwiddie Road where they forced the 6th Regiment New York Volunteer Cavalry and part of a Michigan regiment to retreat.[104][106] Meanwhile, Pickett sent Terry's brigade to break Fitzhugh's defense.[104] Devin had Fitzhugh retire from the strong infantry attack and threat of being outflanked by Munford.[104] Stagg moved forward to deal with the infantry as Fitzhugh had to remove all of his men to the Dinwiddie Road. The two Union brigades could not hold back the combined Confederate infantry and cavalry attack and joined Davies's men at J. Boisseau's farm.[106][107] Pickett then moved patrols through the woods to occupy Adams Road and separate the Union force at J. Boisseau's farm from the Union forces at Dinwiddie Court House.[107][108][109] Each of the two separated segments of Sheridan's command were outnumbered nearly three to one by Pickett's intervening force.[109]

At Sheridan's instruction, Merritt then ordered Devin to take Fitzhugh's and Stagg's brigades to the Boydton Plank Road and move to Dinwiddie Court House.[107][110] After moving to the Boydton Plank Road, Devin made contact with Brigadier General Alfred Gibbs's brigade of Devin's division at the junction of Adams and Brooks Roads.[111] In line with Sheridan's direction, Davies's brigade then crossed Boydton Plank Road under fire and Davies took command as ranking officer of the three brigades.[111] He deployed the 6th Michigan Volunteer Cavalry Regiment to drive back Munford's suddenly pursuing Confederates, which they accomplished with their Spencer repeating carbines.[110][111] Davies then sent Fitzhugh and Stagg to Dinwiddie Court House on a wide movement to and over the Boydton Plank Road where they were rejoined by their men with their led horses.[109][111] The escape of the three Union brigades from Pickett's advance on their position at the J. Boisseau farm was facilitated by the action of Gibbs's and Gregg's brigades against Pickett's force from the south.[109]

Gregg, Gibbs, Smith hold

When Smith's brigade was under attack at 2:00 p.m., Gregg's brigade moved from Dinwiddie Court House to support Smith at Fitzgerald's Ford.[111] Finding the situation under control, Gregg alerted his men to be ready to move to Danse's Ford because of the report of the fighting there.[111] After Sheridan moved the three brigades at J. Boisseau's farm, which he planned to have in position to attack the Confederate flank and rear, he ordered Gregg's brigade to move cross country to hold Adams Road against the Confederates advancing against Stagg, Fitzhugh and Davies.[112] Because Pickett was moving northeasterly away from Dinwiddie Court House, Gibbs, soon joined by Greggs, was able to attack Pickett's flank and rear, forcing him to direct his force back against them.[109]

From the junction of Adams and Brooks Roads, Gibbs was to hold off the Confederate infantry until Gregg moved forward and established contact with Gibbs.[112] Then those Union brigades engaged Pickett's advancing infantry, which had Munford's cavalry guarding their left flank, deflecting then from their drive against the brigades reforming at J. Boisseau's farm.[109][112] Without waiting for the Confederate attack, Gregg's men pushed forward and captured some prisoners.[112]

Gregg and Gibbs held the line on Adams Road just south of Brooks Road for almost two hours before Gibbs's brigade retreated.[112][113] Gregg's position could not be held without Gibbs's support and his men fell back.[114] When Gregg and Gibbs fell back past Ford's Station Road, they took Smith's brigade from Fitzgerald's Ford with them because Smith's force would have been cut off by Pickett's advance where they were positioned.[110][113][114] When forced to withdraw, Smith had held off Fitzhugh Lee's attack at the ford until nearly 5:30 p.m. Smith reformed on the left of Capehart's brigade of Custer's division on Adams Road.[115]

Custer moves up, holds line

At the same time as Sheridan moved Gregg and Gibbs to guard against the Confederate advance on Adams Road, he sent for two of Custer's brigades.[109][113][114][116] As he had done earlier in the day, Sheridan used a fresh division to salvage a situation where Union units had retreated.[113] Custer's third brigade, under Colonel (Brevet Brigadier General) William Wells, was to remain guarding the wagon train.[114] Custer led the brigades of Colonels Alexander C. M. Pennington and Henry Capehart to report to Sheridan at Dinwiddie Court House.[114] Upon Sheridan's order to support and relieve the brigades of Crook's division Custer deployed about three-quarters mile north of Dinwiddie Court House.[113][114][117] Custer directed Pennington to reinforce Smith's brigade at Fitzgerald's Ford. Capehart's troopers were to take position on the left of Adams Road. With Smith retiring from Fitzgerald's Ford, one of Sheridan's aides rode up and told Pennington to deploy on Capehart's right.[114] Battery A, 2nd U.S. Light Artillery also reported to Custer and were positioned on the left.[114] Pennington had only two regiments, the 2nd Ohio Cavalry and 3rd New Jersey Volunteer Cavalry Regiment, forward and positioned a short distance in front of the other Union units.[115]

When Smith fell back from Fitzgerald Ford, Rooney Lee's and Rosser's cavalry divisions had forded Chamberlain's Bed and formed on the right of Pickett's line.[113][115] After Gregg and Gibbs moved back, the Confederates resumed their push on Dinwiddie Court House. As darkness approached, the Confederates came up against Custer's line.[115] A few minutes before the Confederates appeared from the woods at their front, Gregg's brigade moved to the right of Pennington's brigade, in advance of the main Union line and Gibbs's brigade was sent to reunite with Devin's division camped in the rear at Crump's farm.[115] Other reports show Gibbs's brigade in the line of battle.[118]

Final Confederate attack and positions

Pickett decided to have the infantry attack Custer's position down Adams Road while Fitzhugh Lee's cavalry would attack the Union left and Munford's cavalry would cover the field between Adams and Boydton Plank roads.[115] Just before the Confederate attack, Sheridan, Merritt and Custer rode along the line shouting encouragement and exposing themselves to fire.[119] A few civilian visitors rode behind the generals, among them a New York Herald reporter who was slightly wounded.[119]

When the Confederates attacked, Pickett's infantry first assaulted Pennington's advanced line. Pennington's brigade fell back and reformed on crest of a ridge on the right of Adams road in contact with Capehart's brigade.[115][119] Pickett's force made no immediate move to follow up their attack during Pennington's retirement.[113][115] Pennington's force had time to throw up fence rail barricades before receiving another attack. When the Confederate infantry finally resumed the attack, Custer's reorganized defensive line, using repeating rifles, twice drove them back.[119][120] On the left, Fitzhugh Lee's cavalry attacked Smith's men, who continued to hold out despite heavy losses, until they finally ran out of ammunition near dark.[113] "By presenting a good front, without a cartridge," Smith's retiring force discouraged a further attack against them as they occupied a stronger position further south and pretended they had ammunition.[113][120][121] As dark was coming on, Custer led Capehart's dismounted men in a charge that drove the Confederates back, seeming to drain their remaining energy.[121]

By this time, the night had become very dark and Pickett ordered the Confederate attack ended in the face of Custer's resistance.[70][120] Colonel Munford later criticized Pickett for making this decision, stating the Confederates had lost "a golden opportunity" and that "daylight had nothing to do with it."[122] Nonetheless, the opposing sides continued to fire at each other for hours after dark.[123][124]

The two armies' battle lines were very close to each other at the end of the day's battle, in places only about 100 yards (91 m) apart.[113] Pickett's infantry was across Adams road with Fitzhugh Lee's cavalry on the right and Munford's cavalry on the left. Confederate pickets extended from G. U. Brooks' farm on the left to Fitzgerald's Ford on the right.[120] Custer's two brigades were holding Sheridan's front and slept on their arms in anticipation of an early morning attack.[120][125] According to their commanders, each side believed the other would be in a perilous position the following morning.[122]

Immediate result; casualties

Although only a partial victory which did not remove Sheridan from the field, the Battle of Dinwiddie Court House temporarily gave the initiative to the Confederates. Union cavalry, most armed with seven shot repeating carbines or rifles, fought both Confederate cavalry and infantry and slowed the spirited Confederate progress throughout the day. Sheridan's delaying actions were effective at several points but the Union cavalry was pushed back almost to Dinwiddie Court House by the end of the day.[120][126] Nonetheless, the Confederates had suffered additional losses and could not hold their advanced position.[120]

The Confederates did not report their casualties and losses.[120] Historian A. Wilson Greene has written that the best estimate of Confederate casualties is 360 cavalry, 400 infantry, 760 total.[126] Statements show that some Confederates also were taken prisoner.[112] Sheridan suffered 40 killed, 254 wounded, 60 missing, total 354.[126][127] Pickett lost General Terry to a disabling injury. He was replaced as brigade commander by Colonel Robert M. Mayo.[128]

Sheridan's messages to Grant

Late in the afternoon Grant sent his aide-de-camp Lieutenant Colonel Horace Porter to report on Sheridan's situation.[129] He arrived as Gregg's and Gibb's brigades were falling back from the junction of Adams and Brooks roads. Porter met Sheridan just before reaching Dinwiddie Court House. Sheridan told Porter he had had one of the liveliest days in his experience, fighting infantry and cavalry with only cavalry.[122][129] Since his men were concentrating on high ground just north of Dinwiddie Court House, he would hold his position at all hazards. Sheridan reiterated that with a corps of infantry, he could cut off the whole force that Lee had detached and sent against him. Sheridan said that Pickett was in more danger than he was.[122][129]

Historian A. Wilson Greene has stated that the significance of the battle transcended the modest number of casualties.[126] As Sheridan told Colonel Porter: "This force is in more danger than I am - if I am cut off from the Army of the Potomac, it is cut off from Lee's army, and not a man in it should ever be allowed to get back to Lee. We at last have drawn the enemy's infantry out of its fortifications, and this is our chance to attack it."[126][130]

Sheridan asked Porter to hasten back to Grant and to ask Grant to send him the VI Corps but Porter repeated Grant's earlier statement to Sheridan that Wright was on the right of the Union line and the only infantry corps that could promptly join Sheridan was Warren's V Corps.[131] Sheridan appears not to have been as confident as he led Porter to believe because in a letter to Grant sent with a later dispatch via an aide, Colonel John Kellogg, he wrote that "This force (Pickett's) is too strong for us. I will hold on to Dinwiddie Court-House until I am compelled to leave."[122][132] Porter made his report to Grant at Dabney's Mill at 7:00 p.m.[129] The later reports carried to both Meade and Grant via Sheridan's brother Michael, one of his aides, and Colonel Kellogg caused them to conclude that Sheridan was in a desperate position and needed fast reinforcement.[133]

Aftermath

V Corps moves; additional orders

The Confederates won the day on March 31 at Dinwiddie Court House by pushing the Union cavalry into a tight position from which they might be further attacked and dislodged.[70][134]

Despite Sheridan's later criticism of Warren for moving slowly and his removal of Warren from command the next day, when at the end of the Battle of White Oak Road Warren heard the sound of the distant battle receding toward Dinwiddie Court House, he sent Brigadier General Joseph J. Bartlett's brigade of Griffin's division to reinforce Sheridan intending that Bartlett attack Pickett's flank.[135][136] Moving cross country, Bartlett's men drove Confederate pickets from Dr. Boisseau's farm, just east of Crump Road.[137] Since it was dark when Bartlett's men reach Gravelly Run, they did not try to cross but engaged the Confederates on the other side with sniper fire.[137] The dark night hid the size of Bartlett's force from close scrutiny.[137]

At about 6:30 p.m., when Meade learned more about the location of Pickett's and Sheridan's forces, he ordered Warren to send his relief column down the Boydton Plank Road, but Bartlett had been gone too long to be easily recalled.[138] Warren sent three regiments that Bartlett had detached to guard artillery and wagons down the Boydton Plank Road under Colonel (Brevet Brigadier General) Alfred L. Pearson and reported this to Meade.[139] Since the Gravelly Run bridge on the Boydton Plank Road had been broken down by the Confederates, Pearson was delayed.[139] At about 8:20 p.m., Warren told Meade about the needed bridge repair and possible delay but Meade did not pass the information to Sheridan.[140][141] Meade told Warren to have his entire force ready to move.[142] By 9:17 p.m., Warren was ordered to withdraw from the line and send a division to Sheridan at once.[143]

At 9:45 p.m., Meade first advised Grant of Bartlett's forward location at Dr. Boisseau's farm and inquired of Grant whether Warren's entire corps should go to help Sheridan. Grant agreed to follow Meade's advice that II Corps could hold the Boydton Plank Road Line and that two divisions might move to the position held by Bartlett at Dr. Boisseau's farm and one to Dinwiddie, rather than have all three divisions move to Dinwiddie Court House. Grant directed that Meade tell Sheridan about the dispositions and that Sheridan should take direction of the forces being sent to him. Meade did not tell Grant that the plan to move Warren's entire corps to Sheridan's aid was Warren's idea.[144]

When Grant then notified Sheridan that the V Corps and Ranald Mackenzie's cavalry division from the Army of the James had been ordered to his support, he gratuitously and without any basis said that Warren should reach him "by 12 tonight."[123][140][145] It was impossible for the tired V Corps soldiers to cover about 6 miles (9.7 km) on dark, muddy roads with a bridge out in about an hour.[123][140][145][146] Through the night, no one gave Sheridan accurate and complete information about Warren's dispositions, logistical situation and when he received his orders.[146] Nonetheless, Warren's supposed failure to meet his schedule was something for which Sheridan would hold Warren to account.[123][140][145][147]

Meade's further order to send Griffin's division down the Boydton Plank Road and Ayres's and Crawford's divisions to join Bartlett at Dr. Boisseau's farm so they could attack the rear of the Confederate force did not acknowledge the large Confederate force at Dr. Boisseau's farm and the needed repair of the bridge.[145] Warren also received information from a staffer that a Confederate cavalry force under Brigadier General William P. Roberts held the junction of Crump Road and White Oak Road, threatening a direct move.[145]

Because of the disposition of his divisions, to save time, Warren sent Ayres's division to support Sheridan first.[146][148] Warren's message to Meade about this change and the unlikelihood he could move against the Confederate flank and rear because of the large Confederate force at Gravelly Run near Dr. Boisseau's house was delayed due to a break in the telegraph line.[148] Warren's implementation of his orders was delayed due to the availability of only six staff officers that night.[148] Further delays were encountered by the need for to keep the movements of the V Corps from the Union line quiet to avoid Confederate attack from the nearby White Oak Road line.[149]

Humphrey's II Corps was advised to fill in for the V Corps after their movement. Humphrey's replied that his corps could reoccupy its position from the morning of March 31. He sent a message to Warren at 12:30 a.m. asking for Warren's schedule so he could synchronize his movements with Warren's.

Meade learned of the Gravelly Run bridge problem when the telegraph was restored at about 11:45 p.m.[150] Warren rejected Meade's suggestion to consider alternate routes because it would take too long to move his corps.[151] Ayres had received Warren's order to move to the Boydton Plank Road at about 10:00 p.m. This required him to move over about two miles of rough country and cross a branch Gravelly Run.[151] Warren allowed Crawford's and Griffin's men to rest where they were until he learned that Ayres's division had made contact with Sheridan's.[151]

Warren was told that the Gravelly Run bridge was completed at 2:05 a.m.[152] Ayres's division arrived at Sheridan's position near dawn. As predicted by Warren, the effect of Bartlett's appearance threatening Pickett's flank was enough for Pickett to withdraw to Five Forks, which the Confederates had done by the time Ayres reach Dinwiddie Court House.[136][153][154] One of Sheridan's staff officers met Ayres and told him they should have turned on to Brooks Road, a mile back.[155] Ayres returned to Brooks Road, where a lone Confederate picket promptly fled and Ayres's men settled down for a rest until 2:00 p.m.[155]

Sheridan had sent a message to Warren at 3:00 a.m., which did not reach his headquarters until 4:50 a.m., in which he told Warren of the disposition of his forces. Mistakenly thinking that Warren had a division at J. Boisseau's farm in the rear and almost on the flank of the Confederates, Sheridan wanted Warren to attack the Confederates.[155][156] None of Warren's units had been at J. Boisseau's farm. The closest had been at Dr. Boisseau's farm, 1.25 miles (2.01 km) to the north and that unit, Bartlett's brigade, had been recalled.[157] So Warren proceeded to supervise the withdrawal of Crawford's and Griffin's divisions.[157]

About 5:00 a.m., Griffin's division was told to move to the left to J. Boisseau's house.[157] Since Warren did not know Pickett had withdrawn his force, he still expected Griffin to be able to intercept them.[157] Griffin's force moved in line of battle with great care because they thought they might strike the Confederate force from White Oak Road while moving toward the Crump Road.[158] The Confederates did not attack and Warren remained with Crawford until he reached Crump Road.[158]

Warren and his staff then rode to join Griffin at about 9:00 a.m. Griffin had met Devin's cavalry division at J. Boisseau's where he stopped his division and reported to Sheridan.[159] Sheridan rode up, encountered Brigadier General Joshua Chamberlain and asked him where Warren was. Chamberlain replied that he thought he was at the rear of the column.[159] Sheridan exclaimed: "That's just where I should expect him to be."[159] Warren's men knew this was an unfair comment because Warren had never shown a lack of personal bravery.[159] Sheridan instructed Griffin to place his men 0.5 miles (0.80 km) south of J. Boisseau's farm, while Ayres's remained 0.75 miles (1.21 km) south of Griffin.[159] Warren and Crawford's division arrived soon thereafter.[159]

At 6:00 a.m., Meade's Chief of Staff, Brigadier General Alexander S. Webb, had sent an order to Warren to report to Sheridan for further orders.[160] Two of Warren's divisions had done so within an hour of that message.[161][162] A staff officer rode up to Warren at about 9:30 a.m. and handed him Webb's message. At the same time that Webb sent this message to Warren, 6:00 a.m., Meade sent a telegram to Grant stating that Warren would be at Dinwiddie soon with his whole corps and would require further orders.[160] Warren reported to Meade on the successful movement of the corps and stated that while he had not personally met with Sheridan, Griffin had spoken with him.[160] The failure of Warren to report directly to Sheridan may have contributed to his relief from command later on April 1.[160] Warren reported to Sheridan about 11:00 a.m.[163]

When Grant learned that Mackenzie's cavalry division had completed their assignment of guarding the withdrawal of wagon trains from the front, he ordered that Mackenzie and his men report to Sheridan at Dinwiddie Court House. Breaking camp at 3:30 a.m., Mackenzie's troopers rode toward Dinwiddie Court House over the Monk's Neck and Vaughan Roads.[164]

Pickett withdraws to Five Forks

Pickett realized his position was untenable after he learned between 9:00 p.m. and 10:00 p.m. that Bartlett's brigade was on its way to reinforce Sheridan, exposing his force to flanking Union infantry attack.[136][153][154] So Pickett withdrew to Five Forks by 5:00 a.m., giving up any advantage his attack on Sheridan might have gained.[153][154][165] Bartlett's brigade was only the lead unit for all of Griffin's and Crawford's divisions which were put on the march later that night and would have trapped Pickett's force between them and Sheridan's troops.[154] This would have given the Confederate force no apparent alternatives other than surrender or flight to the west.[166] Pickett's retreat gave him an opportunity to defend Five Forks and the South Side Railroad.[167]

When Sheridan discovered the Confederates were pulling back, he sent Custer's division, mostly dismounted, in pursuit on the left and Devin's mounted division in pursuit on the right.[156] A few artillery pieces and Gregg's brigade from Crook's corps moved forward in support.[156] As noted in the previous section, Sheridan had received wrong information so he thought the V Corps was in the rear and almost on the flank of the Confederates and therefore he mistakenly thought V Corps could launch an early, severe attack on Pickett's force.[155] Without infantry support, Sheridan did not press his divisions to carry the attack by themselves.[156]

The slow withdrawal and narrow roads kept the last of the Confederate force from reaching Five Forks until midmorning.[168] When the Confederates reached Five Forks, they began to improve the trenches and fortifications, including establishing a return or refusal of the line running north of the left or eastern side of their trenches.[167][169] While attention was given to improving the refused left flank, Pickett did not have the earthwork line that had been initially constructed when his men had reached Five Forks much improved when his men returned from Dinwiddie Court House. Not only did the line consist only of slim pine logs with a shallow ditch in front but Pickett's disposition of forces was poor. The cavalry in particular were placed in wooded areas inundated by heavy streams so that they could only move to the front by a narrow road.[170][171]

After Pickett returned to Five Forks, he supposedly received Robert E. Lee's telegram ordering him to hold Five Forks "at all hazards."[168] Historian Edward Longacre notes that this story came from Pickett's widow, La Salle Corbell Pickett, who has become known for her fictitious accounts of episodes of Pickett's career.[168] Longacre states that no copy of the telegram has ever been found.[168] He also writes that Pickett's campaign report only says that Lee ordered him to hold his position "so as to protect the road to Ford's Depot," 7 miles (11 km) from Five Forks and that he asked Lee to create a diversion for his men.[168] Longacre does acknowledge that many historians have accepted the story of Lee's command verbatim.[168][172]

Prelude to Five Forks

Warren's gains along the White Oak Road on March 31, 1865 and the movement of Warren's divisions which sent Pickett's men back to Five Forks from Dinwiddie Court House and later positioned his corps with Sheridan's force set the stage for the Confederate defeat at the Battle of Five Forks the day after the battle and the Union breakthrough at the Third Battle of Petersburg on April 2, 1865.[79]

Notes

- ↑ Bearss, Edwin C., with Bryce A. Suderow. The Petersburg Campaign. Vol. 2, The Western Front Battles, September 1864 – April 1865. El Dorado Hills, CA: Savas Beatie, 2014. ISBN 978-1-61121-104-7. p. 329.

- 1 2 3 4 Bearss, 2014, p. 351.

- 1 2 Kennedy, Frances H., ed., The Civil War Battlefield Guide, 2nd ed., Houghton Mifflin Co., 1998, ISBN 978-0-395-74012-5. p. 413.

- ↑ Bearss, Edwin C., with Bryce A. Suderow. The Petersburg Campaign. Vol. 2, The Western Front Battles, September 1864 – April 1865. El Dorado Hills, CA: Savas Beatie, 2014. ISBN 978-1-61121-104-7. p. 411.

- ↑ Bearrs, 2014, p. 311.

- ↑ Winik, Jay. April 1865: The Month That Saved America. New York: HarperCollins, 2006. ISBN 978-0-06-089968-4. First published 2001. p.79.

- ↑ Hess, Earl J. In the Trenches at Petersburg: Field Fortifications & Confederate Defeat. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2009. ISBN 978-0-8078-3282-0. pp. 18–37.

- ↑ Beringer, Richard E., Herman Hattaway, Archer Jones, and William N. Still, Jr. Why the South Lost the Civil War. Athens: University of Georgia Press, 1986. ISBN 978-0-8203-0815-9. pp. 331–332.

- ↑ Trudeau, Noah Andre. The Last Citadel: Petersburg, Virginia, June 1864–April 1865. Baton Rouge: Louisiana State University Press, 1991. ISBN 978-0-8071-1861-0. p. 18.

- ↑ Weigley, Russell F. A Great Civil War: A Military and Political History, 1861–1865. Bloomington and Indianapolis: Indiana University Press, 2000. ISBN 978-0-253-33738-2. p. 433.

- ↑ Greene, A. Wilson. The Final Battles of the Petersburg Campaign: Breaking the Backbone of the Rebellion. Knoxville: University of Tennessee Press, 2008. ISBN 978-1-57233-610-0. p. 154.

- ↑ Calkins, Chris. The Appomattox Campaign, March 29 – April 9, 1865. Conshohocken, PA: Combined Books, 1997. ISBN 978-0-938-28954-8. pp. 14, 16.

- ↑ Hess, 2009, p. 253.

- ↑ Longacre, Edward G. The Cavalry at Appomattox: A Tactical Study of Mounted Operations During the Civil War's Climactic Campaign, March 27 – April 9, 1865. Mechanicsburg, PA: Stackpole Books, 2003. ISBN 978-0-8117-0051-1. p. 39.

- ↑ Greene, 2008, p. 111.

- ↑ Trudeau, 1991, pp. 324–325.

- ↑ Hattaway, Herman, and Archer Jones. How the North Won: A Military History of the Civil War. Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 1983. ISBN 978-0-252-00918-1. pp. 669–671.pp. 669–671.

- 1 2 Trudeau, 1991, pp. 337–352.

- ↑ Greene, 2008, p. 108.

- ↑ Davis, William C. An Honorable Defeat: The Last Days of the Confederate Government. New York: Harcourt, Inc., 2001. ISBN 978-0-15-100564-2. p. 49.

- ↑ Greene, 2008, pp. 114–115.

- ↑ Hess, 2009, pp. 252–254.

- ↑ Keegan, John, The American Civil War: A Military History. New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 2009. ISBN 978-0-307-26343-8. p. 257.

- ↑ Marvel, William. Lee's Last Retreat: The Flight to Appomattox. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2002. ISBN 978-0-8078-5703-8. p. 11.

- ↑ Trudeau, 1991, p. 366.

- ↑ Greene, 2008, p. 154"

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Calkins, 1997, p. 16.

- ↑ Hattaway, Herman, and Archer Jones. How the North Won: A Military History of the Civil War. Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 1983. ISBN 978-0-252-00918-1. pp. 669–671.

- ↑ Calkins, 1997, p. 12.

- 1 2 Calkins, 1997, p. 14.

- 1 2 Bonekemper, Edward H., III. A Victor, Not a Butcher: Ulysses S. Grant's Overlooked Military Genius. Washington, DC: Regnery, 2004. ISBN 978-0-89526-062-8, p. 230.

- ↑ Bearss, 2014, p. 312.

- ↑ Bearss, 2014, p. 317.

- ↑ Greene, 2008, p. 152.

- ↑ Calkins, 1997, pp. 18–19.

- ↑ Bearss, 2014, pp. 336–337.

- 1 2 Horn, 1999, p. 222.

- 1 2 3 4 Calkins, 1997, p. 20.

- ↑ Greene, 2009, pp. 155–158.

- ↑ Trulock, Alice Rains. In the Hands of Providence: Joshua L. Chamberlain and the American Civil War. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1992. ISBN 978-0-8078-2020-9.. p. 230.

- ↑ Calkins, 2009, p. 17.

- ↑ Greene, 2009, pp. 140, 154–158.

- ↑ Greene, 2009, p. 158.

- 1 2 Hess, 2009, pp. 255–260.

- ↑ Calkins, 1997, pp. 20–21.

- ↑ Trulock, 1992, pp. 231–238.

- ↑ Salmon, John S., The Official Virginia Civil War Battlefield Guide, Stackpole Books, 2001, ISBN 978-0-8117-2868-3. p. 459.

- 1 2 Hess, 2009, p. 256.

- 1 2 3 Greene, 2008, p. 162.

- ↑ Hess, 2009, p. 255.

- 1 2 Horn, 1999, p. 221.

- ↑ Calkins, 1997, p. 21.

- 1 2 3 Hess, 2009, p. 257.

- ↑ Longacre, 2003, pp. 17, 52–53.

- ↑ Bearss, 2014, p. 337.

- 1 2 3 Bearss, 2014, p. 356.

- ↑ Greene, 2009, p. 169.

- ↑ Lee would have moved men from Lieutenant General James Longstreet's force north of the James River but largely due to demonstrations and deceptions by the remaining divisions of Major General Godfrey Weitzel's XXV Corps (Twenty-Fifth Corps), Longstreet thought that he still confronted Ord's entire Army of the James almost three days after Ord had gone with two divisions of the XXIV Corps, a division of the XXV Corps and Brigadier General Ranald Mackenzie's cavalry division to the Union lines south of Petersburg. Bearss, 2014, p. 338.

- 1 2 Bearss, 2014, p. 353.

- 1 2 Bearss, 2014, p. 354.

- 1 2 Bearss, 2014, p. 357.

- ↑ Trulock, 1992, p. 242.

- ↑ Bearss, 2014, p. 358.

- ↑ Greene, 2008, p. 163.

- ↑ Trulock, 1992, pp. 242–244.

- ↑ Trulock, 1992, p. 244.

- ↑ Trulock, 1992, p. 245.

- 1 2 3 Greene, 2008, p. 170.

- ↑ Bearss, 2014, p. 411.

- 1 2 3 4 Calkins, 1997, p. 24.

- ↑ Hess, 2009, p. 258.

- 1 2 3 Greene, 2008, p. 172.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Hess, 2009, p. 259.

- 1 2 Calkins, 1997, p. 25.

- ↑ Bearss, 2014, p. 423.

- ↑ Bearss, 2014, pp. 424–425.

- ↑ Calkins, 1997, p.26

- ↑ Bearrs, 2014, p. 432

- 1 2 3 4 5 Greene, 2009, p. 174.

- ↑ Bearss, 2014, p. 433.

- ↑ Bearss, 2014, p. 434.

- ↑ Calkins, 1997, p. 201.

- ↑ Lowe, David W. White Oak Road in Kennedy, Frances H., ed., The Civil War Battlefield Guide, 2nd ed., Houghton Mifflin Co., 1998, ISBN 978-0-395-74012-5. p. 417. gives the casualties as Union 1,781 and Confederate as 900–1,235.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Greene, 2009, p. 175.

- ↑ Bearss, 2014, p. 380.

- ↑ Longacre, 2003, p. 65.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Bearss, 2014, p. 381.

- 1 2 3 Longacre, 2003, p. 66.

- 1 2 Bearss, 2014, p. 382.

- ↑ Greene, 2008, pp. 175–176.

- 1 2 3 Greene, 2008, p. 176.

- 1 2 3 Bearss, 2014, p. 385.

- 1 2 3 Bearss, 2014, p. 384.

- 1 2 3 4 Longacre, 2003, p. 68.

- 1 2 3 Bearss, 2014, p. 387.

- 1 2 Bearss, 2014, p. 386.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 Longacre, 2003, p. 69.

- 1 2 3 Bearss, 2014, p. 388.

- 1 2 3 4 Bearss, 2014, p. 389.

- 1 2 3 4 Bearss, 2014, p. 390.

- 1 2 3 4 Bearss, 2014, p. 392.

- ↑ Bearss, 2014, p. 392–393.

- 1 2 3 Bearss, 2014, p. 393.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Bearss, 2014, p. 394.

- ↑ Longacre, 2003, pp. 69–70.

- 1 2 Longacre, 2003, p. 70.

- 1 2 3 Bearss, 2014, p. 396.

- ↑ Greene, 2008, p. 177.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 Starr, Steven. The Union Cavalry in the Civil War: The War in the East from Gettysburg to Appomattox, 1863–1865. Volume 2. Baton Rouge: Louisiana State University Press, 2007. Originally published 1981. ISBN 978-0-8071-3292-0. p. 438.

- 1 2 3 Longacre, 2003, p. 72.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Bearss, 2014, p. 397.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Bearss, 2014, p. 398.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 Greene, 2008, p. 178.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 Bearss, 2014, p. 400.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 Bearss, 2014, p. 402.

- ↑ Longacre, 2003, p. 71.

- ↑ Starr, 2007 ed., p. 440.

- ↑ Starr, 2007 ed., p. 441.

- 1 2 3 4 Longacre, 2003, p. 74.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 Bearss, 2014, p. 403.

- 1 2 Longacre, 2003, p. 75.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Longacre, 2003, p. 76.

- 1 2 3 4 Longacre, 2003, p. 78.

- ↑ Historian Edward G. Longacre reminds readers that Pickett's primary objective was not to capture Dinwiddie Court House but to protect the Confederate right flank and access to the South Side Railroad. Longacre, 2003, p. 79.

- ↑ The Union wagon train was at the junction of Vaughan Road and Monk's Neck Road over night.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Greene, 2008, p. 179.

- ↑ Bearss, 2014, p. 404 states the Union loss was about 450 according to the Official Records of the War of the Rebellion. Longacre, 2003, p. 75 says Sheridan took "nearly 500" casualties.

- ↑ Bearss, 2014, pp. 403–404.

- 1 2 3 4 Bearss, 2014, p. 404.

- ↑ Also quoted by Bearss, 2014, p. 404; Longacre, 2003, p. 76, Calkins, 1997, p. 24.

- ↑ Longacre, 2003, pp. 76–77

- ↑ Bearss, 2014, pp. 404–405.

- ↑ Starr, 2007 ed., p. 442.

- ↑ Longacre, 2003, p. 75 calls the outcome a tie.

- ↑ Bearrs, 2014, p. 437.

- 1 2 3 Calkins, 1997,p. 27.

- 1 2 3 Bearrs, 2014, p. 438.

- ↑ Bearss, 2014, p. 439.

- 1 2 Bearss, 2014, p. 440.

- 1 2 3 4 Starr, 2007 ed., p. 444.

- ↑ Bearss, 2014, p. 442.

- ↑ Bearss, 2014, p. 443.

- ↑ Bearss, 2014, p. 444.

- ↑ Bearss, 2014, p. 446.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Bearss, 2014, p. 447.

- 1 2 3 Greene, 2009, p. 181"

- ↑ In his "Memoirs", written after a court of inquiry had concluded that Warren had been unfairly removed from command by Sheridan, Sheridan wrote simply that he was disappointed that Warren could not move faster to trap Pickett. Longacre, 2003, p. 80.

- 1 2 3 Bearss, 2014, p. 448.

- ↑ Bearss, 2014, p. 449.

- ↑ Bearss, 2014, p. 450.

- 1 2 3 Bearss, 2014, p. 451.

- ↑ Bearss, 2014, pp. 445, 452.

- 1 2 3 Greene, 2009, p. 182.

- 1 2 3 4 Longacre, 2003, p. 79.

- 1 2 3 4 Bearss, 2014, p. 453.

- 1 2 3 4 Longacre, 2003, p. 80.

- 1 2 3 4 Bearss, 2014, p. 454.

- 1 2 Bearss, 2014, p. 455.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Bearss, 2014, p. 456.

- 1 2 3 4 Bearss, 2014, 457.

- ↑ Bearss, 2014, pp. 457–458.

- ↑ Longacre, 2003, p. 86.

- ↑ Bearss, 2014, p. 458.

- ↑ Bearss, 2014, p. 460.

- ↑ The 5:00 a.m. time is given by Douglas Southall Freeman in Freeman, Douglas S. Lee's Lieutenants: A Study in Command. Cedar Mountain to Chancellorsville. Vol. 2 of 3 vols. New York: Scribner, 1943. ISBN 978-0-684-10176-7. p. 661. Starr, 2007 ed., p. 445 cites an eyewitness account of Roger Hannaford, a Union quartermater sergeant, that the retreat began at 3:00 a.m.

- ↑ Greene, 2009, pp. 182–183.

- 1 2 Greene, 2009, p. 183.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Longacre, 2003, p. 81.

- ↑ Longacre, 2003, p. 82.

- ↑ Hess, 2009, p. 261.

- ↑ Longacre, Edward G. Lee's Cavalrymen: A History of the Mounted Forces of the Army of Northern Virginia. Mechanicsburg, PA: Stackpole Books, 2002. ISBN 978-0-8117-0898-2. p. 327.

- ↑ Gordon, Lesley J. General George E. Pickett in Life and Legend (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1998) and Gallagher, Gary. A Widow and Her Soldier: LaSalle Corbell Pickett as Author of the George E. Pickett Letters, Virginia Magazine of History and Biography, 94 (July 1986): 32 9–44 support Longacre's view.

References

- Beringer, Richard E., Herman Hattaway, Archer Jones, and William N. Still, Jr. Why the South Lost the Civil War. Athens: University of Georgia Press, 1986. ISBN 978-0-8203-0815-9.

- Bearss, Edwin C., with Bryce A. Suderow. The Petersburg Campaign. Vol. 2, The Western Front Battles, September 1864 – April 1865. El Dorado Hills, CA: Savas Beatie, 2014. ISBN 978-1-61121-104-7.

- Bonekemper, Edward H., III. A Victor, Not a Butcher: Ulysses S. Grant's Overlooked Military Genius. Washington, DC: Regnery, 2004. ISBN 978-0-89526-062-8.

- Calkins, Chris. The Appomattox Campaign, March 29 – April 9, 1865. Conshohocken, PA: Combined Books, 1997. ISBN 978-0-938-28954-8.

- Davis, William C. An Honorable Defeat: The Last Days of the Confederate Government. New York: Harcourt, Inc., 2001. ISBN 978-0-15-100564-2.

- Greene, A. Wilson. The Final Battles of the Petersburg Campaign: Breaking the Backbone of the Rebellion. Knoxville: University of Tennessee Press, 2008. ISBN 978-1-57233-610-0.

- Hattaway, Herman, and Archer Jones. How the North Won: A Military History of the Civil War. Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 1983. ISBN 978-0-252-00918-1. pp. 669–671.

- Hess, Earl J. In the Trenches at Petersburg: Field Fortifications & Confederate Defeat. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2009. ISBN 978-0-8078-3282-0.

- Keegan, John, The American Civil War: A Military History. New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 2009. ISBN 978-0-307-26343-8.

- Kennedy, Frances H., ed., The Civil War Battlefield Guide, 2nd ed., Houghton Mifflin Co., 1998, ISBN 978-0-395-74012-5.

- Longacre, Edward G. The Cavalry at Appomattox: A Tactical Study of Mounted Operations During the Civil War's Climactic Campaign, March 27 – April 9, 1865. Mechanicsburg, PA: Stackpole Books, 2003. ISBN 978-0-8117-0051-1.

- Longacre, Edward G. Lee's Cavalrymen: A History of the Mounted Forces of the Army of Northern Virginia. Mechanicsburg, PA: Stackpole Books, 2002. ISBN 978-0-8117-0898-2.

- Marvel, William. Lee's Last Retreat: The Flight to Appomattox. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2002. ISBN 978-0-8078-5703-8.

- Salmon, John S., The Official Virginia Civil War Battlefield Guide, Stackpole Books, 2001, ISBN 978-0-8117-2868-3.

- Starr, Steven. The Union Cavalry in the Civil War: The War in the East from Gettysburg to Appomattox, 1863–1865. Volume 2. Baton Rouge: Louisiana State University Press, 2007. Originally published 1981. ISBN 978-0-8071-3292-0.

- Trudeau, Noah Andre. The Last Citadel: Petersburg, Virginia, June 1864–April 1865. Baton Rouge: Louisiana State University Press, 1991. ISBN 978-0-8071-1861-0.

- Trulock, Alice Rains. In the Hands of Providence: Joshua L. Chamberlain and the American Civil War. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1992. ISBN 978-0-8078-2020-9.

- Weigley, Russell F. A Great Civil War: A Military and Political History, 1861–1865. Bloomington and Indianapolis: Indiana University Press, 2000. ISBN 978-0-253-33738-2.

- Winik, Jay. April 1865: The Month That Saved America. New York: HarperCollins, 2006. ISBN 978-0-06-089968-4. First published 2001.