| Fortification of Dorchester Heights | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the American Revolutionary War | |||||||

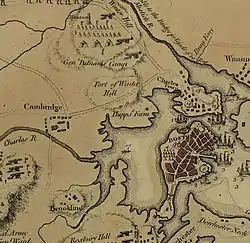

Detail of a 1775 map of Boston, with Dorchester Heights at the bottom right | |||||||

| |||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

|

|

| ||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

|

|

| ||||||

| Strength | |||||||

| 2,000–6,000 on Dorchester Heights | 10,000 in Boston | ||||||

The Fortification of Dorchester Heights was a decisive action early in the American Revolutionary War that precipitated the end of the siege of Boston and the withdrawal of British troops from that city.

On March 4, 1776, troops from the Continental Army under George Washington's command occupied Dorchester Heights, a series of low hills with a commanding view of Boston and its harbor, and mounted powerful cannons there threatening the city and the Navy ships in the harbor. General William Howe, commander of the British forces occupying Boston, planned an attack to dislodge them. However, after a snowstorm prevented its execution, Howe withdrew instead. British forces, accompanied by Loyalists who had fled to the city during the siege, evacuated the city on March 17 and sailed to Halifax, Nova Scotia.

Background

The siege of Boston began on April 19, 1775, when, in the aftermath of the Battles of Lexington and Concord, Colonial militia surrounded the city of Boston.[1] Benedict Arnold, a captain in the Connecticut militia, arrived with his troops to support the siege. He informed the Massachusetts Committee of Safety that cannons and other valuable military stores were stored at the lightly defended Fort Ticonderoga in New York, and proposed its capture. On May 3, the Committee gave Arnold a colonel's commission and authorized him to raise troops and lead a mission to capture the fort.[2] Arnold, in conjunction with Ethan Allen, his Green Mountain Boys, and militia forces from Connecticut and western Massachusetts, captured the fort and all of its armaments on May 10.[3]

After George Washington took command of the army outside Boston in July 1775, the idea of bringing the cannons from Ticonderoga to the siege was raised by Colonel Henry Knox. Knox was eventually given the assignment to transport weapons from Ticonderoga to Cambridge. Knox went to Ticonderoga in November 1775, and, over the course of three winter months, moved 60 tons[4] of cannons and other armaments by boat, horse and ox-drawn sledges, and manpower, along poor-quality roads, across two semi-frozen rivers, and through the forests and swamps of the sparsely inhabited Berkshires to the Boston area.[5][6] Historian Victor Brooks has called Knox's successful effort "one of the most stupendous feats of logistics" of the entire war.[7]

Geography and strategy

The British military leadership, headed by General William Howe, had long been aware of the importance of the Dorchester Heights, which, along with the heights of Charlestown, had commanding views of Boston and its outer harbor. The harbor was vital to the British, as the Royal Navy, at first under Admiral Samuel Graves, and later under Admiral Molyneux Shuldham,[8] provided protection for the troops in Boston, as well as transportation of supplies to the besieged city. Early in the siege, on June 15, the British agreed on the plan of seizing both of these heights, beginning with those in Dorchester, which had a better view of the harbor than the Charlestown hills.[9] It was the leaking of this plan that precipitated events leading to the Battle of Bunker Hill.[10]

Neither the British nor the Americans had the daring to take and fortify the heights; but both armies knew of its strategic importance in the war.[11] When Washington took command of the siege in July 1775, he considered taking the unoccupied Dorchester Heights, but rejected the idea, feeling the army was not ready to deal with the likely British attack on the position.[12] The subject of an attempt on the heights was again discussed in early February 1776, but the local Committee of Safety believed the British troop strength too high, and important military supplies like gunpowder too low, to warrant action at that time.[13] By the end of February, Knox had arrived with the cannon from Ticonderoga, as had additional supplies of powder and shells.[14] Washington decided the time was right to act.

Fortification

Washington first placed some of the heavy cannons from Ticonderoga at Lechmere's Point and Cobble Hill in Cambridge, and on Lamb's Dam in Roxbury.[15] As a diversion against the planned move on the Dorchester Heights, he ordered these batteries to open fire on the town on the night of March 2, which fire the British returned, without significant casualties on either side. These cannonades were repeated on the night of March 3, while preparations for the taking of the heights continued.[16]

On the night of March 4, 1776, the batteries opened fire again, but this time the fire was accompanied by action.[17] This cannonade was continued on three successive nights, and while the British were focused on this, the Americans made preparations to implement a plan devised by Rufus Putnam to break the long siege.[18][19][20]

The American objective was to get cannon onto Dorchester Heights, and fortify the position. However, the ground was frozen, so digging was impossible. Putnam, who had been a millwright, devised a plan using chandeliers (heavy timbers, 10 feet long, used as frames) and fascines. These were prefabricated out of sight of the British.[18][19][20]

General John Thomas and about 2,500 troops quietly marched to the top of Dorchester Heights, hauling tools, the prefabricated fortifications and cannon placements. Hay bales were placed between the path taken by the troops and the harbor in order to muffle the sounds of the activity. Throughout the night, these troops and their relief labored at hauling cannon and building the parapet overlooking the town and the harbor. General Washington was present to provide moral support and encouragement, reminding them that March 5 was the sixth anniversary of the Boston Massacre.[21] By 4 a.m., they had constructed fortifications that were proof against small arms and grapeshot. Work continued on the positions, with troops cutting down trees and constructing abbatis to impede any British assault on the works.[17] The outside of the works also included rock-filled barrels that could be rolled down the hill at attacking troops.[22][18][19][20]

"The rebels have done more in one night than my whole army would have done in a month."

General Howe, March 5, 1776[23]

Washington anticipated that General Howe and his troops would either flee or try to take the hill,[24] an action that would have probably been reminiscent of the Battle of Bunker Hill, which was a disaster for the British.[25] If Howe decided to launch an attack on the heights, Washington planned to launch an attack against the city from Cambridge. As part of the preparations, he readied two floating batteries and boats sufficient to carry almost 3,000 troops.[26] Washington's judgment of Howe's options was accurate; they were exactly the options Howe considered.

British reaction

Admiral Shuldham, commander of the British fleet, declared that the fleet was in danger unless the position on the heights was taken. Howe and his staff then determined to contest the occupation of the heights, and made plans for an assault, preparing to send 2,400 men under cover of darkness to attack the position.[27] Washington, notified of British movements, increased the forces on the heights until there were nearly 6,000 men on the Dorchester lines.[28] However, a snow storm began late on March 5 and halted any chance of a battle for several days.[29] By the time the storm subsided, Howe reconsidered launching an attack, reasoning that preserving the army for battle elsewhere was of higher value than attempting to hold Boston.[30]

On March 8, intermediaries delivered an unsigned paper [31] informing Washington that the city would not be burned to the ground if his troops were allowed to leave unmolested.[32] After several days of activity, and several more of bad weather, the British forces departed Boston by sea on March 17 and sailed to Halifax, Nova Scotia, taking with them more than 1,000 Loyalist civilians.[33]

_-_general_view.jpg.webp)

Legacy

The fortifications on the Heights were maintained through the end of the war, and then abandoned. During the War of 1812, the Heights were refortified and occupied against potential British invasion. Following that war, the fortifications were completely abandoned, and, in the later years of the 19th century, the Dorchester hills were used as a source of fill for Boston's expanding coastline.[34]

In 1902, following revived interest in the local history, the Dorchester Heights Monument was constructed on the (remaining) high ground in what is now South Boston.[34] The large Irish population in the area was also instrumental in having March 17 (which is also Saint Patrick's Day) named as the Evacuation Day holiday in Suffolk County, Massachusetts, which includes the city of Boston.[35][36]

The Dorchester Heights National Historic Site was added to the National Register of Historic Places in 1966, and in 1978 came under the administration of the National Park Service as part of Boston National Historical Park.[34]

Notes

- ↑ Frothingham (1903), pp. 91–93

- ↑ Palmer (2006), pp. 84–85

- ↑ Palmer (2006), pp. 88–90

- ↑ Ware (2000), p. 18

- ↑ Ware (2000), pp. 19–24

- ↑ N. Brooks (1900), p. 38

- ↑ V. Brooks (1999), p. 210

- ↑ Frothingham (1903), p. 292

- ↑ McCullough, David G.. "Dorchester Heights." 1776. New York City, New York: Simon & Schuster, 2005. 70. Print.

- ↑ French (1911), p. 254

- ↑ McCullough, David G.. "Dorchester Heights." 1776. New York City, New York: Simon & Schuster, 2005. 71. Print.

- ↑ Frothingham (1903), p. 218

- ↑ Frothingham (1903), pp. 290–291

- ↑ Frothingham (1903), p. 295

- ↑ V. Brooks (1999), p. 224

- ↑ French (1911), p. 406

- 1 2 V. Brooks (1999), p. 225

- 1 2 3 Hubbard, Robert Ernest. Major General Israel Putnam: Hero of the American Revolution, pp. 158, McFarland & Company, Inc., Jefferson, North Carolina, 2017. ISBN 978-1-4766-6453-8.

- 1 2 3 Philbrick, Nathaniel. Bunker Hill: A City, a Siege, a Revolution, pp. 274–7, Viking Penguin, New York, New York, 2013 (ISBN 978-0-670-02544-2).

- 1 2 3 Livingston, William Farrand. Israel Putnam: Pioneer, Ranger and Major General, 1718–1790, pp. 269–70, G.P. Putnam's Sons, New York and London, 1901.

- ↑ Gilman (1876), p. 59

- ↑ V. Brooks (1999), p. 226

- ↑ Frothingham (1903), p. 298

- ↑ Frothingham (1903), p. 296

- ↑ Frothingham (1903), p. 194. British win, but suffer over 1,000 casualties.

- ↑ French (1911), p. 390

- ↑ French (1911), p. 412

- ↑ V. Brooks (1999), p. 229

- ↑ Frothingham (1903), pp. 298–300

- ↑ V. Brooks (1999), p. 231

- ↑ McCullough (2005), p. 99

- ↑ Frothingham (1903), pp. 303–305

- ↑ Frothingham (1903), p. 311

- 1 2 3 National Park Service

- ↑ O'Connor, p. 124

- ↑ MA List of legal holidays

References

- Brooks, Noah (1900). Henry Knox, a Soldier of the Revolution: Major-general in the Continental Army, Washington's Chief of Artillery, First Secretary of War Under the Constitution, Founder of the Society of the Cincinnati; 1750–1806. New York: G.P. Putnam's Sons. OCLC 77547631.

- Brooks, Victor (1999). The Boston Campaign. Conshohocken, PA: Combined Publishing. ISBN 1-58097-007-9. OCLC 42581510.

- French, Allen (1911). The Siege of Boston. New York: Macmillan. OCLC 3927532.

- Frothingham, Richard (1903). History of the Siege of Boston, and of the Battles of Lexington, Concord, and Bunker Hill: Also an Account of the Bunker Hill Monument. Boston: Little, Brown. OCLC 221368703.

- Gilman, Arthur; Dudley, Dorothy; Greely, Mary Williams (1876). Theatrum Majorum: The Cambridge of 1776. Cambridge, MA: Lockwood, Brooks. OCLC 4073105.

- McCullough, David (2005). 1776. New York, NY: Simon & Schuster.

- O'Connor, Thomas H. (1994). South Boston, My Home Town: The History of an Ethnic Neighborhood. Boston: UPNE. ISBN 978-1-55553-188-1. OCLC 29387180.

- Palmer, Dave Richard (2006). George Washington and Benedict Arnold: A Tale of Two Patriots. Washington, DC: Regnery Publishing. ISBN 978-1-59698-020-4. OCLC 69027634.

- Ware, Susan (2000). Forgotten Heroes: Inspiring American Portraits from Our Leading Historians. Portland, OR: Simon and Schuster. ISBN 978-0-684-86872-1. OCLC 45179918.

- "Massachusetts List of Legal Holidays". Massachusetts Secretary of State. Retrieved 2008-12-16.

- "NPS page for Dorchester Heights". National Park Service. Retrieved 2009-01-12.