| Capture of Fort Ticonderoga | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the American Revolutionary War | |||||||

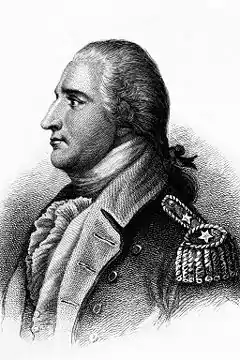

An idealized depiction of Ethan Allen demanding the fort's surrender | |||||||

| |||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

|

militia of the Connecticut Colony militia of the Province of Massachusetts Bay |

26th Regiment of Foot[1] | ||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

|

Ethan Allen Benedict Arnold |

William Delaplace | ||||||

| Strength | |||||||

|

83 at Ticonderoga[2] 50 at Crown Point[3] 35 at Saint-Jean[4] |

48 at Ticonderoga[5] 9 at Crown Point[6] 21 at Saint-Jean[4] | ||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||

|

1 captured near Fort Saint-Jean[7] | All captured | ||||||

Location within New York | |||||||

The capture of Fort Ticonderoga occurred during the American Revolutionary War on May 10, 1775, when a small force of Green Mountain Boys led by Ethan Allen and Colonel Benedict Arnold surprised and captured the fort's small British garrison. The cannons and other armaments at Fort Ticonderoga were later transported to Boston by Colonel Henry Knox in the noble train of artillery and used to fortify Dorchester Heights and break the standoff at the siege of Boston.

Capture of the fort marked the beginning of offensive action taken by the Americans against the British.[lower-alpha 1] After seizing Ticonderoga, a small detachment captured the nearby Fort Crown Point on May 11. Seven days later, Arnold and 50 men raided Fort Saint-Jean on the Richelieu River in southern Quebec, seizing military supplies, cannons, and the largest military vessel on Lake Champlain.

Although the scope of this military action was relatively minor, it had significant strategic importance. It impeded communication between northern and southern units of the British Army, and gave the nascent Continental Army a staging ground for the invasion of Quebec later in 1775. It also involved two larger-than-life personalities in Allen and Arnold, each of whom sought to gain as much credit and honor as possible for these events. Most significantly, in an effort led by Henry Knox, artillery from Ticonderoga was dragged across Massachusetts to the heights commanding Boston Harbor, forcing the British to withdraw from that city.

Background

In 1775, Fort Ticonderoga's location did not appear to be as strategically important as it had been in the French and Indian War, when the French famously defended it against a much larger British force in the 1758 Battle of Carillon, and when the British captured it in 1759. After the 1763 Treaty of Paris, in which the French ceded their North American territories to the British, the fort was no longer on the frontier of two great empires, guarding the principal waterway between them.[9] The French had blown up the fort's powder magazine when they abandoned the fort, and it had fallen further into disrepair since then. In 1775 it was garrisoned by only a small detachment of the 26th Regiment of Foot, consisting of two officers and forty-six men, with many of them "invalids" (soldiers with limited duties because of disability or illness). Twenty-five women and children lived there as well. Because of its former significance, Fort Ticonderoga still had a high reputation as the "gateway to the continent" or the "Gibraltar of America", but in 1775 it was, according to historian Christopher Ward, "more like a backwoods village than a fort."[5]

Even before shooting started in the American Revolutionary War, American Patriots were concerned about Fort Ticonderoga. The fort was a valuable asset for several reasons. Within its walls was a collection of heavy artillery including cannons, howitzers, and mortars, armaments that the Americans had in short supply.[10][11] The fort was situated on the shores of Lake Champlain, a strategically important route between the Thirteen Colonies and the British-controlled northern provinces. British forces placed there would expose the colonial forces in Boston to attack from the rear.[10] After the war began with the Battles of Lexington and Concord on April 19, 1775, the British General Thomas Gage realized the fort would require fortification, and several colonists had the idea of capturing the fort.

Gage, writing from the besieged city of Boston following Lexington and Concord, instructed Quebec's governor, General Guy Carleton, to rehabilitate and refortify the forts at Ticonderoga and Crown Point.[12] Carleton did not receive this letter until May 19, well after the fort had been captured.[13]

Benedict Arnold had frequently traveled through the area around the fort, and was familiar with its condition, manning, and armaments. En route to Boston following news of the events of April 19, he mentioned the fort and its condition to members of Silas Deane's militia.[14] The Connecticut Committee of Correspondence acted on this information; money was "borrowed" from the provincial coffers and recruiters were sent into northwestern Connecticut, western Massachusetts, and the New Hampshire Grants (now Vermont) to raise volunteers for an attack on the fort.[15]

John Brown, an American spy from Pittsfield, Massachusetts who had carried correspondence between revolutionary committees in the Boston area and Patriot supporters in Montreal, was well aware of the fort and its strategic value.[9] Ethan Allen and other Patriots in the disputed New Hampshire Grants territory also recognized the fort's value, as it played a role in the dispute over that area between New York and New Hampshire.[16] Whether either took or instigated action prior to the Connecticut Colony's recruitment efforts is unclear. Brown had notified the Massachusetts Committee of Safety in March of his opinion that Ticonderoga "must be seized as soon as possible should hostilities be committed by the King's Troops."[16][17]

When Arnold arrived outside Boston, he told the Massachusetts Committee of Safety about the cannons and other military equipment at the lightly defended fort. On May 3, the Committee gave Arnold a colonel's commission and authorized him to command a "secret mission", which was to capture the fort.[18] He was issued £100, some gunpowder, ammunition, and horses, and instructed to recruit up to 400 men, march on the fort, and ship back to Massachusetts anything he thought useful.[19]

Colonial forces assemble

Arnold departed immediately after receiving his instructions. He was accompanied by two captains, Eleazer Oswald and Jonathan Brown, who were charged with recruiting the necessary men. Arnold reached the border between Massachusetts and the Grants on May 6, where he learned of the recruitment efforts of the Connecticut Committee, and that Ethan Allen and the Green Mountain Boys were already on their way north. Riding furiously northward (his horse was subsequently destroyed), he reached Allen's headquarters in Bennington the next day.[20] Upon arrival, Arnold was told that Allen was in Castleton, 50 miles (80 km) to the north, awaiting supplies and more men. He was also warned that, although Allen's effort had no official sanction, his men were unlikely to serve under anyone else. Leaving early the next day, Arnold arrived in Castleton in time to join a war council, where he made a case to lead the expedition based on his formal authorization to act from the Massachusetts Committee.[21]

The force that Allen had assembled in Castleton included about 100 Green Mountain Boys, about 40 men raised by James Easton and John Brown at Pittsfield, and an additional 20 men from Connecticut.[22] Allen was elected colonel, with Easton and Seth Warner as his lieutenants.[21] When Arnold arrived on the scene, Samuel Herrick had already been sent to Skenesboro and Asa Douglas to Panton with detachments to secure boats. Captain Noah Phelps, a member of the "Committee of War for the Expedition against Ticonderoga and Crown Point", had reconnoitered the fort disguised as a peddler seeking a shave. He saw that the fort walls were dilapidated, learned from the garrison commander that the soldiers' gunpowder was wet, and that they expected reinforcements at any time.[23][24] He reported this intelligence to Allen, following which they planned a dawn raid.[23]

Many of the Green Mountain Boys objected to Arnold's wish to command, insisting that they would go home rather than serve under anyone other than Ethan Allen. Arnold and Allen worked out an agreement, but no documented evidence exists concerning the deal. According to Arnold, he was given joint command of the operation. Some historians have supported Arnold's contention, while others suggest he was merely given the right to march next to Allen.[lower-alpha 2]

Capture of the fort

By 11:30 pm on May 9, the men had assembled at Hand's Cove (in what is now Shoreham, Vermont) and were ready to cross the lake to Ticonderoga. Boats did not arrive until 1:30 am, and they were inadequate to carry the whole force.[25] Eighty-three of the Green Mountain Boys made the first crossing with B. Arnold and E. Allen, with Major Asa Douglas going back for the rest.[2] As dawn approached, Allen and Arnold became fearful of losing the element of surprise, so they decided to attack with the men at hand. The only sentry on duty at the south gate fled his post after his musket misfired, and the Americans rushed into the fort. The Patriots then roused the small number of sleeping troops at gunpoint and began confiscating their weapons. Allen, Arnold, and a few other men charged up the stairs toward the officers' quarters. Lieutenant Jocelyn Feltham, the assistant to Captain William Delaplace, was awakened by the noise, and called to wake the captain.[26] Stalling for time, Feltham demanded to know by what authority the fort was being entered. Allen, who later claimed that he said it to Captain Delaplace, replied, "In the name of the Great Jehovah and the Continental Congress!"[27] Delaplace finally emerged from his chambers (fully clothed, not with "his breeches in his hand", as Allen would later say) and surrendered his sword.[27]

Nobody was killed in the battle. The only injury was to one American, Gideon Warren,[28] who was slightly injured by a sentry with a bayonet.[8] Eventually, as many as 400 men arrived at the fort, which they plundered for liquor and other provisions. Arnold, whose authority was not recognized by the Green Mountain Boys, was unable to stop the plunder. Frustrated, he retired to the captain's quarters to await forces that he had recruited, reporting to the Massachusetts Provincial Congress that Allen and his men were "governing by whim and caprice" at the fort, and that the plan to strip the fort and send armaments to Boston was in peril.[29] When Delaplace protested the seizure of his private liquor stores, Allen issued him a receipt for the stores, which he later submitted to Connecticut for payment.[30] Arnold's disputes with Allen and his unruly men were severe enough that there were times when some of Allen's men drew weapons.[29]

On May 12, Allen sent the prisoners to Connecticut's Governor Jonathan Trumbull with a note saying "I make you a present of a Major, a Captain, and two Lieutenants of the regular Establishment of George the Third."[31] Arnold busied himself over the next few days with cataloging the military equipment at Ticonderoga and Crown Point, a task made difficult by the fact that walls had collapsed on some of the armaments.[32]

Crown Point and the raid on Fort Saint-Jean

Seth Warner sailed a detachment up the lake and captured nearby Fort Crown Point, garrisoned by only nine men. It is widely recorded that this capture occurred on May 10; this is attributed to a letter Arnold wrote to the Massachusetts Committee of Safety on May 11, claiming that an attempt to sail up to Crown Point was frustrated by headwinds. However, Warner claimed, in a letter dated May 12 from "Head Quarters, Crown Point", that he "took possession of this garrison" the day before.[6] It appears likely that, having failed on May 10, the attempt was repeated the next day with success, as reported in Warner's memoir.[33] A small force was also sent to capture Fort George on Lake George, which was held by only two soldiers.[34]

Troops recruited by Arnold's captains began to arrive, some after seizing Philip Skene's schooner Katherine and several bateaux at Skenesboro.[35][36] Arnold rechristened the schooner Liberty. The prisoners had reported that the lone British warship on Lake Champlain was at Fort Saint-Jean, on the Richelieu River north of the lake. Arnold, uncertain whether word of Ticonderoga's capture had reached Saint-Jean, decided to attempt a raid to capture the ship. He had Liberty outfitted with guns, and sailed north with 50 of his men on May 14.[37] Allen, not wanting Arnold to get the full glory for that capture, followed with some of his men in bateaux, but Arnold's small fleet had the advantage of sail, and pulled away from Allen's boats. By May 17, Arnold's small fleet was at the northern end of the lake. Seeking intelligence, Arnold sent a man to reconnoiter the situation at Fort Saint-Jean. The scout returned later that day, reporting that the British were aware of the fall of Ticonderoga and Crown Point, and that troops were apparently on the move toward Saint-Jean. Arnold decided to act immediately.[38]

Rowing all night, Arnold and 35 of his men brought their bateaux near the fort. After a brief scouting excursion, they surprised the small garrison at the fort, and seized supplies there, along with HMS Royal George, a seventy-ton sloop-of-war.[39] Warned by their captives that several companies were on their way from Chambly, they loaded the more valuable supplies and cannons on the George, which Arnold renamed the Enterprise. Boats that they could not take were sunk, and the enlarged fleet returned to Lake Champlain.[4] This activity was observed by Moses Hazen, a retired British officer who lived near the fort. Hazen rode to Montreal to report the action to the local military commander, and then continued on to Quebec City, where he reported the news to General Carleton on May 20. Major Charles Preston and 140 men were immediately dispatched from Montreal to Saint-Jean in response to Hazen's warning.[40]

Fifteen miles out on the lake, Arnold's fleet met Allen's, which was still heading north. After an exchange of celebratory gunfire, Arnold opened his stores to feed Allen's men, who had rowed 100 miles (160 km) in open boats without provisions. Allen, believing he could seize and hold Fort Saint-Jean, continued north, while Arnold sailed south.[41] Allen arrived at Saint-Jean on May 19, where he was warned that British troops were approaching by a sympathetic Montreal merchant who had raced ahead of those troops on horseback.[42] Allen, after penning a message for the merchant to deliver to the citizens of Montreal, returned to Ticonderoga on May 21, leaving Saint-Jean just as the British forces arrived.[42][43] In Allen's haste to escape the arriving troops, three men were left behind; one was captured, but the other two eventually returned south by land.[7]

Aftermath

Ethan Allen and his men eventually drifted away from Ticonderoga, especially once the alcohol began to run out, and Arnold largely controlled affairs from a base at Crown Point.[34][44] He oversaw the fitting of the two large ships, eventually taking command of Enterprise because of a lack of knowledgeable seamen. His men began rebuilding Ticonderoga's barracks, and worked to extract armaments from the rubble of the two forts and build gun carriages for them.[44]

Connecticut sent about 1,000 men under Colonel Benjamin Hinman to hold Ticonderoga, and New York also began to raise militia to defend Crown Point and Ticonderoga against a possible British attack from the north. When Hinman's troops arrived in June, there was once again a clash over leadership. None of the communications to Arnold from the Massachusetts committee indicated that he was to serve under Hinman; when Hinman attempted to assert authority over Crown Point, Arnold refused to accept it, as Hinman's instructions only included Ticonderoga.[45] The Massachusetts committee eventually sent a delegation to Ticonderoga. When they arrived on June 22 they made it clear to Arnold that he was to serve under Hinman. Arnold, after considering for two days, disbanded his command, resigned his commission, and went home, having spent more than £1,000 of his own money in the effort to capture the fort.[46]

When Congress received news of the events, it drafted a second letter to the inhabitants of Quebec, which was sent north in June with James Price, another sympathetic Montreal merchant. This letter, and other communications from the New York Congress, combined with the activities of vocal American supporters, stirred up the Quebec population in the summer of 1775.[47]

When news of the fall of Ticonderoga reached England, Lord Dartmouth wrote that it was "very unfortunate; very unfortunate indeed".[48]

Repercussions in Quebec

News of the capture of Ticonderoga and Crown Point, and especially the raids on Fort Saint-Jean, electrified the Quebec population. Colonel Dudley Templer, in charge of the garrison at Montreal, issued a call on May 19 to raise a militia for defense of the city, and requested Indians living nearby to also take up arms. Only 50 men, mostly French-speaking landowning seigneurs and petty nobility, were raised in and around Montreal, and they were sent to Saint-Jean; no Indians came to their aid. Templer also prevented merchants sympathetic to the American cause from sending supplies south in response to Allen's letter.[49]

General Carleton, notified by Hazen of the events on May 20, immediately ordered the garrisons of Montreal and Trois-Rivières to fortify Saint-Jean. Some troops garrisoned at Quebec were also sent to Saint-Jean. Most of the remaining Quebec troops were dispatched to a variety of other points along the Saint Lawrence, as far west as Oswegatchie, to guard against potential invasion threats.[50] Carleton then traveled to Montreal to oversee the defense of the province from there, leaving the city of Quebec in the hands of Lieutenant Governor Hector Cramahé.[51] Before leaving, Carleton prevailed on Monsignor Jean-Olivier Briand, the Bishop of Quebec, to issue his own call to arms in support of the provincial defense, which was circulated primarily in the areas around Montreal and Trois-Rivières.[52]

Later actions near Ticonderoga

In July 1775, General Philip Schuyler began using the fort as the staging ground for the invasion of Quebec that was launched in late August.[53] In the winter of 1775–1776, Henry Knox directed the transportation of the guns of Ticonderoga to Boston. The guns were placed upon Dorchester Heights overlooking the besieged city and the British ships in the harbor, prompting the British to evacuate their troops and Loyalist supporters from the city in March 1776.[54]

Benedict Arnold again led a fleet of ships at the Battle of Valcour Island, and played other key roles in thwarting Britain's attempt to recapture the fort in 1776.[55] The British did recapture the fort in July 1777 during the Saratoga campaign, but had abandoned it by November after Burgoyne's surrender at Saratoga.[56]

Broken communications

Although Fort Ticonderoga was not at the time an important military post, its capture had several important results. Rebel control of the area meant that overland communications and supply lines between British forces in Quebec and those in Boston and later New York were severed, so the British military command made an adjustment to their command structure.[57] This break in communication was highlighted by the fact that Arnold, on his way north to Saint-Jean, intercepted a message from Carleton to Gage, detailing the military troop strengths in Quebec.[58] Command of British forces in North America, previously under a single commander, was divided into two commands. General Carleton was given independent command of forces in Quebec and the northern frontier, while General William Howe was appointed Commander-in-Chief of forces along the Atlantic coast, an arrangement that had worked well between Generals Wolfe and Amherst in the French and Indian War.[57] In this war, however, cooperation between the two forces would prove to be problematic and would play a role in the failure of the Saratoga campaign in 1777, as General Howe apparently abandoned an agreed-upon northern strategy, leaving General John Burgoyne without southern support in that campaign.[59]

War of words between Allen and Arnold

Beginning on the day of the fort's capture, Allen and Arnold began a war of words, each attempting to garner for himself as much credit for the operation as possible. Arnold, unable to exert any authority over Allen and his men, began to keep a diary of events and actions, which was highly critical and dismissive of Allen.[34] Allen, in the days immediately after the action, also began to work on a memoir. Published several years later (see Further reading), the memoir fails to mention Arnold at all. Allen also wrote several versions of the events, which John Brown and James Easton brought to a variety of Congresses and committees in New York, Connecticut, and Massachusetts. Randall (1990) claims that Easton took accounts written by both Arnold and Allen to the Massachusetts committee, but conveniently lost Arnold's account on the way, ensuring that Allen's version, which greatly glorified his role in the affair, would be preferred.[60] Smith (1907) indicates that it was highly likely that Easton was interested in claiming Arnold's command for himself.[61] There was clearly no love lost between Easton and Arnold. Allen and Easton returned to Crown Point on June 10 and called a council of war while Arnold was with the fleet on the lake, a clear breach of military protocol. When Arnold, whose men now dominated the garrison, asserted his authority, Easton insulted Arnold, who responded by challenging Easton to a duel. Arnold later reported, "On refusing to draw like a gentleman, he having a [sword] by his side and cases of loaded pistols in his pockets, I kicked him very heartily and ordered him from the Point."[62]

See also

Explanatory notes

- ↑ Up until this point all battles fought by the Americans were in a defensive capacity, e.g. the Battles of Lexington and Concord.

- ↑ Pell (1929), p. 81, claims there is no documentary evidence. Boatner (1974) (pp. 1101–1102) notes that although Ward believes Arnold merely had the right to march next to Allen, Allen French argues otherwise in The Taking of Ticonderoga in 1775. Bellesiles (1995), p. 117, claims that Allen offered Arnold the right to march at the head of the column to placate Arnold.

Citations

- ↑ P. Nelson (2000), p. 61

- 1 2 Bellesiles (1995), p. 117

- ↑ Smith (1907), p. 144

- 1 2 3 Randall (1990), p. 104

- 1 2 Ward (1952), Volume 1, p. 69

- 1 2 Chittenden (1872), p. 109

- 1 2 Jellison (1969), p. 131

- 1 2 Ward (1952), Volume 1, p. 68.

- 1 2 Randall (1990), p. 86.

- 1 2 Ward (1952), Volume 1, p. 64.

- ↑ Drake (1873), p. 130.

- ↑ Gage (1917), p. 397.

- ↑ Lanctot (1967), p. 49.

- ↑ Randall (1990), p. 85.

- ↑ Randall (1990), p. 87.

- 1 2 Bellesiles (1995), p. 116.

- ↑ Boatner (1974), p. 1101.

- ↑ Ward (1952), Volume 1, p. 65.

- ↑ J. Nelson (2006), p. 15.

- ↑ Randall (1990), p. 86–89.

- 1 2 Randall (1990), p. 90.

- ↑ Smith (1907), pp. 124–125.

- 1 2 Randall (1990), p. 91.

- ↑ Phelps (1899), p. 204.

- ↑ Jellison (1969), pp. 114–115.

- ↑ Randall (1990), p. 95.

- 1 2 Randall (1990), p. 96.

- ↑ New York, Pension Claims by Disabled Revolutionary War Veterans, 1779–1789

- 1 2 Randall (1990), p. 97.

- ↑ Jellison (1969), p. 124.

- ↑ Chittenden (1872), p. 49.

- ↑ J. Nelson (2006), p. 40.

- ↑ Chipman (1848), p. 141

- 1 2 3 Randall (1990), p. 98

- ↑ Smith (1907), p. 155

- ↑ Morrissey (2000), p. 10

- ↑ Randall (1990), p. 101

- ↑ Randall (1990), p. 103

- ↑ Smith (1907), p. 157

- ↑ Lanctot (1967), pp. 44,50

- ↑ Randall (1990), p. 105

- 1 2 Lanctot (1967), p. 44

- ↑ Randall (1990), p. 106

- 1 2 J. Nelson (2006), p. 53.

- ↑ J. Nelson (2006), p. 61.

- ↑ Randall (1990), pp. 128–129.

- ↑ Lanctot (1967), pp. 55–60.

- ↑ Jellison (1969), p. 120.

- ↑ Lanctot (1967), p. 45.

- ↑ Lanctot (1967), p. 50.

- ↑ Lanctot (1967), p. 53.

- ↑ Lanctot (1967), p. 52.

- ↑ Smith (1907), p. 250.

- ↑ French (1911), pp. 387–419.

- ↑ Randall (1990), pp. 290–314.

- ↑ Morrissey (2000), p. 86.

- 1 2 Mackesy (1993), p. 40.

- ↑ J. Nelson (2006), p. 42.

- ↑ Van Tyne (1905), pp. 161–162.

- ↑ Randall (1990), p. 99.

- ↑ Smith (1907), p. 184.

- ↑ Randall (1990), p. 121.

Cited works

- Bellesiles, Michael A (1995). Revolutionary Outlaws: Ethan Allen and the Struggle for Independence on the Early American Frontier. Charlottesville, Virginia: University of Virginia Press. ISBN 978-0-8139-1603-3.

- Boatner, Mark Mayo III (1974) [1966]. Encyclopedia of the American Revolution (revised ed.). New York: McKay. ISBN 0-8117-0578-1.

- Chipman, Daniel (1848). Memoir of Colonel Seth Warner. Middlebury, Vermont: L. W. Clark. OCLC 4403351.

- Chittenden, Lucius Eugene (1872). The Capture of Ticonderoga: Annual Address Before the Vermont Historical Society Delivered at Montpelier, Vt., on Tuesday Evening, October 8, 1872. Montpelier, Vermont: Vermont Historical Society. ISBN 0-7884-0802-X. OCLC 181111316.

- Drake, Francis Samuel (1873). Life and correspondence of Henry Knox: Major-General in the American Revolutionary Army. Boston: S.G. Drake. OCLC 2358685.

- French, Allen (1911). The Siege of Boston. New York: Macmillan. ISBN 0-659-90572-8. OCLC 3927532.

- Gage, Thomas (1931). The correspondence of General Thomas Gage, volume 1. Yale University Press. ISBN 978-0-208-00812-1.

- Jellison, Charles A (1969). Ethan Allen: Frontier Rebel. Syracuse, New York: Syracuse University Press. ISBN 0-8156-2141-8.

- Lanctot, Gustave (1967). Canada and the American Revolution 1774–1783. London: Harvard University Press. OCLC 70781264.

- Mackesy, Piers (1993). The War for America: 1775–1783. Lincoln, Nebraska: University of Nebraska Press. ISBN 0-8032-8192-7.

- Morrissey, Brendan (2000). Saratoga 1777: Turning Point of a Revolution. Oxford: Osprey Publishing. ISBN 978-1-85532-862-4.

- Nelson, James L. (2006). Benedict Arnold's Navy: The Ragtag Fleet that Lost the Battle of Lake Champlain But Won the American Revolution. Camden, Maine: McGraw-Hill Professional. ISBN 978-0-07-146806-0.

- Nelson, Paul David (2000). General Sir Guy Carleton, Lord Dorchester: Soldier-statesman of Early British Canada. Madison, New Jersey: Fairleigh Dickinson Univ Press. ISBN 978-0-8386-3838-5.

- Pell, John (1929). Ethan Allen. Boston: Houghton Mifflin. ISBN 978-0-8369-6919-1.

- Phelps, Oliver Seymour; Servin, Andrew T. (1899). The Phelps family of America and their English ancestors, with copies of wills, deeds, letters, and other interesting papers, coats of arms and valuable records (two volumes). Pittsfield, Massachusetts: Eagle Publishing Company. OCLC 39187566.

- Randall, Willard Sterne (1990). Benedict Arnold: Patriot and Traitor. New York: William Morrow. ISBN 1-55710-034-9.

- Smith, Justin Harvey (1907). Our Struggle for the Fourteenth Colony: Canada, and the American Revolution, Volume 1. New York: G.P. Putnam's Sons. ISBN 978-0-306-70633-2. OCLC 259236.

- Van Tyne, Claude Halstead (1905). The American Revolution, 1776–1783. New York: Harper & Brothers. OCLC 23093734.

- Vermont Historical Society (1871). Collections of the Vermont Historical Society vol. 2. Montpelier, Vermont: Vermont Historical Society. OCLC 19358021.

- Ward, Christopher (1952). The War of the Revolution. New York: Macmillan. ISBN 1-56852-576-1. OCLC 425995.

- Wilson, Barry (2001). Benedict Arnold: A Traitor in Our Midst. Montreal: McGill-Queen's Press. ISBN 978-0-7735-2150-6.

Further reading

- Allen, Ethan (1849). Ethan Allen's Narrative of the Capture of Ticonderoga: And of His Captivity and Treatment by the British. Burlington, Vermont: C. Goodrich and S. B. Nichols. ISBN 0-665-22135-5. OCLC 17008777.

- French, Allen (1928). The Taking of Ticonderoga in 1775: The British Story; A Study of Captors and Captives. Cambridge, Massachusetts: Harvard University Press. OCLC 651774.

External links

- Fort Ticonderoga National Historic Landmark

- "Capture of Ticonderoga", excerpt from Thrilling Incidents in American History by J. W. Barber, 1860.