| Battle of Elands River | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the Second Boer War | |||||||

A soldier from the 3rd New South Wales Bushmen at Elands River a year after the battle | |||||||

| |||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

|

| |||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

|

| Koos de la Rey | ||||||

| Strength | |||||||

|

297 Australians 201 Rhodesians 3 Canadians 3 Britons | 2,000 – 3,000 | ||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||

|

12 soldiers killed and 36 wounded 4 civilians killed and 15 wounded | Unknown | ||||||

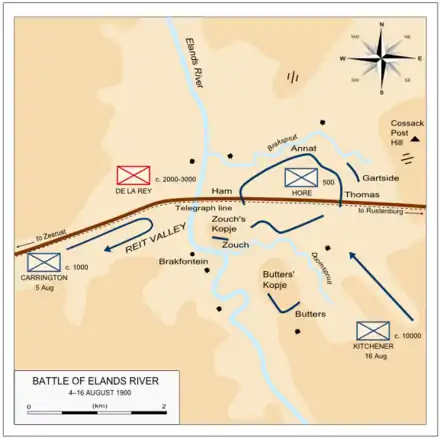

The Battle of Elands River was an engagement of the Second Boer War that took place between 4 and 16 August 1900 in western Transvaal. The battle was fought at Brakfontein Drift near the Elands River between a force of 2,000 to 3,000 Boers and a garrison of 500 Australian, Rhodesian, Canadian and British soldiers, which was stationed there to protect a British supply dump that had been established along the route between Mafeking and Pretoria. The Boer force, which consisted of several commandos under the overall leadership of Koos de la Rey, was in desperate need of provisions after earlier fighting had cut it off from its support base. As a result, it was decided to attack the garrison along the Elands River in an effort to capture the supplies located there.

Over the course of 13 days, the Elands River supply dump was heavily shelled from several artillery pieces that were set up around the position, while Boers equipped with small arms and machine guns surrounded the garrison and kept the defenders under fire. Outnumbered and isolated, the defenders were asked to surrender by the Boer commander, but refused. The siege was subsequently lifted when the garrison was relieved by a 10,000-strong flying column led by Lord Kitchener. The relief effort, although successful, drew forces away from efforts to capture a Boer commander, Christiaan de Wet, who ultimately managed to evade British capture. This, along with the difficulty the British had in effecting the relief, buoyed Boer morale although the defenders' efforts also drew praise from Boer commanders.

Background

The first months of the Second Boer War were characterised by the use of large-scale conventional infantry forces by the British, which suffered heavy casualties in engagements with highly mobile Boer forces. Following this, a series of British counter-offensives, including mounted infantry units from the Australian colonies and Canada, among others, managed to capture and secure the main population centres in South Africa by June 1900. Much of the Boer force surrendered with the loss of their supply bases. In response, the Boers, including many who dishonoured their parole after having surrendered, and others who had melted away into civilian life, began a guerrilla warfare campaign. Operating in small groups, Boer commandos attacked columns of troops and supply lines, sniping, ambushing and launching raids on isolated garrisons and supply depots.[1]

As a defensive measure to protect the supply route between Mafeking and Pretoria, the British had established a garrison along the Elands River.[2] Positioned near Brakfontein Drift, now the town of Swartruggens, about 173 kilometres (107 mi) west of Pretoria,[3] the location was developed into a supply dump by the British to supply forces operating in the area and to serve as a way point on the route between Rustenburg and Zeerust.[4] By mid-1900, the supplies that were located at Elands River included between 1,500 and 1,750 horses, mules and cattle, a quantity of ammunition, food and other equipment worth over 100,000 pounds, and over 100 wagons.[5][6] As the supplies were vulnerable to Boer raids, a garrison, spread across several positions, had been established.[7]

The main position was at a farm located about 1 kilometre (0.6 mi) away from the river, occupying a small ridge, while two smaller positions were established on hills to the south, closer to the river, which were later called Zouch's Kopje and Butters' Kopje.[7] The area was bracketed by two creeks – the Brakspruit to the north and the Doornspruit to the south – which flowed west into the river. A telegraph line ran through the farm along the Zeerust–Rustenburg road, which crossed the river at a ford about 1 kilometre (0.62 mi) west of the farm.[8] While the ground to the north, south and west of the supply dump dropped to the river where the Reit Valley opened towards Zeerust, 50 kilometres (31 mi) away, the ground to the east of the farm rose towards a high point which came to be known as Cossack Post Hill. The hill was used by the garrison defending the post to send messages to Rustenburg – 70 kilometres (43 mi) away – using a heliograph.[9]

Prelude

On 3 August, an 80-wagon supply convoy arrived at Elands River from Zeerust, where they were to wait for their escort, a column of 1,000 men from the New South Wales Imperial Bushmen along with South African irregulars, commanded by General Frederick Carrington, to arrive from Mafeking.[4] Desperate for provisions, Boer forces decided to attack the garrison with a view to securing the supplies located there.[7] Prior to the battle, the garrison had received intelligence warning them of the attack. As a result, some actions were taken to fortify the position, with a makeshift defensive perimeter being established utilising stores and wagons to create barricades.[7] Little attempt had been made to dig-in, as the ground around the position was hard and the garrison lacked entrenching tools.[10]

The garrison defending the Elands River post consisted of about 500 men.[7] The majority were Australians, comprising 105 from A Squadron of the New South Wales Citizen Bushmen, 141 from the Queensland Citizen Bushmen, 42 Victorians and nine Western Australians from the 3rd Bushmen Regiment, and two from Tasmania.[5] In addition, there were 201 Rhodesians from the British South Africa Police, the Rhodesia Regiment, the Southern Rhodesian Volunteers, and the Bechuanaland Protectorate Regiment,[11] along with three Canadians and three Britons. A British officer, Lieutenant Colonel Charles Hore, was in overall command. Their only fire support was one or two Maxim machine-guns and an antiquated 7-pounder screw gun, for which there was only about 100 rounds of ammunition.[7][12][13] In addition to the garrison, there were civilians, consisting of Africans working as porters, drivers, or runners and about 30 loyalist European settlers who had moved to the farm prior to being evacuated.[5] Against this, the Boer force, consisting of between 2,000 and 3,000 men drawn from the Rustenburg, Wolmaransstad and Marico commandos,[10] under the overall command of Generals Koos de la Rey and Hermanus Lemmer, possessed five or six 12-pounder field guns for indirect fire, three quick-firing 1-pound pom-poms, which could provide rapid direct fire support,[7] and two machine guns.[12]

Battle

The Boer surrounded the garrison during the night while the latter were occupied singing around their campfires,[4] and began their attack early on 4 August after the garrison had been stood down for breakfast. Rifle shots from snipers positioned in the riverbed announced the commencement of the attack. They were followed by an intense artillery barrage from the Boer guns.[10] One pom-pom and a 12-pounder engaged one of the outposts from the south-west from behind an entrenched position about 2,700 metres (3,000 yd) away on the opposite side of the river, while the main position was engaged by three guns positioned to the east along with a Maxim gun, snipers, a pom-pom and an artillery piece in multiple positions to the north-west about 1,800 metres (2,000 yd) away. A third firing point, about 3,900 metres (4,300 yd) away, consisting of an artillery piece and a pom-pom, engaged the garrison from high ground overlooking the river to the west.[14] In response, the defenders' screw gun returned fire, destroying a farmhouse from which Boers were firing; however, the gun soon jammed.[15] Unanswered, the Boer barrage of around 1,700 shells devastated the oxen and killed around 1,500 horses, mules and cattle.[4][12] Those that remained alive were set free to avoid a stampede.[15] In addition, the telegraph line and considerable stores were destroyed, and a number of casualties inflicted.[7]

In an effort to silence the guns, a small party of Queenslanders under Lieutenant James Annat, sallied 180 metres (200 yd) to attack one of the Boer pom-pom positions, forcing its crew to pack up their weapon and withdraw.[15][16] Nevertheless, the other guns remained in action and the barrage continued throughout the day, before easing as night fell. The defenders then used the brief respite to begin digging in,[4] using their bayonets, and to clear away the dead animals.[15] Casualties during the first day amounted to at least 28, of which eight were killed.[17]

The following morning, 5 August, the Boer gunners continued the shelling, but the effects were limited by the defences dug the night before.[4] About 800 shells were fired on the second day, bringing the total to 2,500 over two days.[7] Later that day, the expected 1000 strong column led by Carrington was ambushed by a Boer force under Lemmer's command about 3 kilometres (1.9 mi) west of the position and, although their casualties consisted of only 17 wounded, Carrington chose to withdraw.[7] The ambush was facilitated by the inadequate reconnaissance provided by Carrington's scouts.[18] The column later destroyed supplies at Groot Marico, Zeerust and Ottoshoop, so that they would not fall into Boer hands,[4] although a large amount of supplies remained usable in many locations, including at Zeerust, and were ultimately captured by the Boers. Carrington's force then withdrew hastily to Mafeking, a decision which damaged his reputation amongst some of his soldiers, particularly the Australians.[19]

When it became apparent that the relief had been turned back, the Boer commander, De la Rey, seeking to end the siege before another relief force could be sent,[18] ordered his men to cease fire and sent a messenger calling upon the garrison to surrender. After the garrison rejected the offer, the shelling resumed and continued throughout the night.[4] Nevertheless, the defenders continued to improve their position, constructing stone sangars and digging their fighting pits deeper,[7] reinforcing them with crates, sacks and wagon wheels.[20] Wood, salvaged from wrecked wagons, was used to provide overhead protection to the positions, several of which were linked with a tunnel.[18] A kitchen was also established, and a makeshift hospital built in the centre of the position using several ambulances and reinforced with wagons filled with dirt and various stores and containers.[20] Although the defenders had repaired their screw gun, they were only able to use it for counter-battery fire sparingly due to lack of ammunition.[16]

After the initial heavy barrage, on the third day of the siege the Boer gunners eased their rate of fire when it became apparent that they were destroying some of the supplies they were trying to capture. Nevertheless, the Boers maintained small arms fire, keeping defenders trapped in their defences during the intense heat of the day; the heat also accelerated the decomposition of the dead animals, the smell of which was considerable.[7] There was no water source within the main camp so patrols under a Rhodesian officer, Captain Sandy Butters,[4] who commanded the southernmost outpost at Butters' Kopje, were sent out at night to collect it from the Elands River, about 800 metres (870 yd) away.[3] During several of these sallies, fire was exchanged and the party had to fight their way back.[4] De la Rey opted not to launch a direct assault on the position to limit his losses. The southern and eastern sides were well protected, but he realised that an approach from the south-west might offer more chance of success.[21] Attempts were made by the Boers to take the kopje to the south of the Doornspruit on two nights – 6 and 7 August in an effort to cut off the defenders' supply of water; however, Rhodesians, under the command of Butters, helped by supporting fire from the Zouch's Kopje near the creek's confluence with the river, repulsed both attacks.[18] A force of 2,000 Boers took part in these efforts, and on the second night attempted to cover their approach by advancing behind a herd of sheep and goats.[22] On 8 August, the post's hospital came under artillery fire, even though it was marked with a Red Cross flag. One of the shells struck it, further wounding some of those receiving treatment.[12]

After five days, De la Rey again called for surrender,[7] as he became concerned about being caught by relief forces. The message was received by Hore around 9:00 am on the fifth day of the siege after several hours of artillery fire.[18] Hore had been suffering from malaria even before the siege and had been largely confined to the post.[10] As a result, command had effectively passed to an Australian, Major Walter Tunbridge from the Queensland Citizen Bushmen.[3] Upon receiving the message, Hore discussed it with the other officers, at which point Tunbridge told him that the Australians refused to surrender.[18] In order to demonstrate the respect with which he held the defence that the garrison had put up, De la Rey offered them safe passage to British lines and was even prepared to allow the officers to retain their revolvers so that they could leave the battlefield with dignity.[7] Once again, however, the offer was rejected,[23] and Hore is reputed to have stated: "I cannot surrender. I am in command of Australians who would cut my throat if I did."[16] Butters took a similar line, repeatedly shouting towards the Boers that "Rhodesians never surrender!"[22][24]

This stand at Brakfontein on the Eland River appears to have been one of the finest deeds of arms of the war. Australians have been so split up during the campaign that though their valour and efficiency were universally recognised, they had no single large exploit which they could call their own. But now they can point to Elands River as proudly as the Canadians at Paardeberg...they were sworn to die before the white flag would wave above them. And so fortune yielded, as fortune will when brave men set their teeth...when the ballad makers of Australia seek for a subject, let them turn to Elands River, for there was no finer fighting in the war.

—Sir Arthur Conan Doyle, in The Great Boer War[16]

As the fighting continued, the British made a second attempt to relieve the garrison, dispatching a force of about 1,000 men under Colonel Robert Baden-Powell from Rustenburg on 6 August. He halted just 13 kilometres (8 mi) from Rustenburg, around the Selous River, about a third of the way, and sent out scouts. Failing to allow a proper reconnaissance, around midday Baden-Powell messaged General Ian Hamilton and turned back, determining the relief effort pointless, citing previous instructions and warnings from Commander-in-Chief of British Forces in South Africa Lord Roberts about becoming isolated,[18] and claiming to have heard gun fire moving westward that suggested the garrison may have been evacuated to the west by Carrington.[25] Based on the reports provided by Carrington upon his return, the British commanders in Pretoria and Mafeking were under the impression that the garrison had surrendered and, as a result, when Baden-Powell's force was about 30 kilometres (19 mi) away from the besieged Elands River garrison at Brakfontein, Lord Roberts ordered him and the rest of Hamilton's force at Rustenburg to return to Pretoria,[4] to focus on capturing Christiaan De Wet, an important Boer commander.[18] Late on 6 August, Roberts learned that Carrington had failed to evacuate the Elands River garrison;[26] in response Roberts ordered Carrington to try again.[19]

The siege continued; however, the size of the Boer force surrounding the garrison dwindled as their attention was drawn to attacks on nearby farms by members of the Kgatla tribe,[27] who were in revolt against the Boers following a series of tenant disputes.[28] The ammunition situation was also concerning de la Rey and, as it became clear that the garrison would continue to hold out, he withdrew his artillery before superior numbers of British troops arrived.[29] Ultimately, only about 200 men from the Wolmaransstad commando remained. As a result, the Boer weight of fire decreased and finally ceased altogether.[30] In response, the defenders sent patrols out to scout the Boer positions and small raiding parties were also sent out at night.[7] These raids failed to confirm that the Boers were retreating and as a result, instead of seizing the initiative the defenders remained largely in their defences, thinking that the Boers were attempting a ruse to draw them out.[30]

On 13 August, the British commanders learned that the garrison was still holding out when they intercepted a message between Boer commanders via a runner.[4][14] Two days later, 10,000 men under the command of Lord Kitchener, set out towards Elands River. As they approached, de la Rey, faced by a superior force, withdrew what remained of his force.[14] Small arms fire around the perimeter ceased on 15 August and the garrison observed rising dust from the withdrawal.[29] That evening, a message was sent to Hore by four Western Australians from a force under Beauvoir de Lisle,[30] and Kitchener's column arrived the following day, on 16 August.[14] Carrington's relief force from Mafeking, having been ordered to make a second attempt by Roberts, backtracked very slowly and ultimately arrived after the siege had been lifted.[19]

Aftermath

Casualties for the defenders amounted to 12 soldiers killed and 36 wounded.[14] In addition, four African porters were killed and 14 wounded, and one loyalist European settler was wounded.[31] Most of the wounded were evacuated to Johannesburg.[31] The loss of animals was heavy, with only 210 left alive out of 1,750.[6] Of the 12 soldiers who were killed, eight were Australians.[32] During the siege, defenders who had been killed were hastily buried under the cover of darkness in a temporary cemetery. At the conclusion of the fighting, the graves were improved with several slate headstones and white rocks to mark the outlines, and a formal funeral was provided. After the war, the dead were exhumed and reburied at Swartruggens Cemetery, with individual crosses replacing the group slate headstones. One of the original slate headstones was brought back to Australia in the 1970s and placed on display in the Australian War Memorial.[12]

Although the behaviour of the defending troops was not beyond reproach, with some becoming drunk during the siege,[32] the commander of the relieving force, Lord Kitchener, told the garrison upon his arrival that their defence had been "remarkable" and that only " ... Colonials could have held out in such impossible circumstances".[32] The garrison's performance was also later lauded by Jan Smuts, who was at the time a senior Boer commander, describing the defenders as " ... heroes who in the hour of trial ...[had risen]... nobly to the occasion".[14] The battle has been described by historian Chris Coulthard-Clark as being " ... perhaps the most notable action involving Australians in South Africa".[14] The writer, Sir Arthur Conan Doyle, who served in a British field hospital at Bloemfontein during 1900 and who later published a series of accounts of the conflict, also highlighted the significance of the battle in The Great Boer War.[16] The flag flown by the garrison during the siege was later displayed in the Cathedral of St Mary and All Saints in Salisbury, Rhodesia.[6]

For their actions during the siege, the Rhodesian commander, Butters, and Captain Albert Duka, a medical officer from Queensland, were invested with the Distinguished Service Order. Three soldiers – Corporal Robert Davenport and Troopers Thomas Borlaise and William Hunt – received the Distinguished Conduct Medal.[31] Borlaise, who had been a miner before enlisting, received his medal for the role he had played in improving the position's defences,[33] while Davenport received the award for rescuing two wounded men under fire.[15] Conversely, Carrington continued nominal command of the Rhodesian Field Force, which became a paper formation, and was sent back to England by the end of the year.[34]

The battle had strategic implications. The difficulty the British had in relieving the garrison served to boost Boer morale, which had been flagging due to earlier reverses, while the act of doing so drew forces away from the cordon that was being set up by the British to capture De Wet,[4] who subsequently managed to escape through the Magaliesberg,[30] which had been abandoned by Baden-Powell during the relief effort. This ultimately prolonged the war, which would continue for almost another two years.[29] Over a year after the siege, on 17 September 1901, another battle was fought along a different Elands River at Modderfontein farm in the then Cape Colony,[35] where a Boer force under Smuts and Deneys Reitz overwhelmed a detachment of the 17th Lancers and raided their camp for supplies.[36]

In Media

The battle is referenced in John Edmond's song 'The Siege at Elands River'.[37]

Notes

- ↑ "Australia and the Boer War, 1899–1902". Australian War Memorial. Retrieved 6 January 2012.

- ↑ Ransford & Kinsey 1979, p. 2

- 1 2 3 Horner 2010, p. 66.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 Wulfsohn 1984.

- 1 2 3 Wilcox 2002, p. 120.

- 1 2 3 Ransford & Kinsey 1979, p. 10.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 Coulthard-Clark 1998, p. 84.

- ↑ Wilcox 2002, p. 119.

- ↑ Wilcox 2002, pp. 119–120.

- 1 2 3 4 Wilcox 2002, p. 122.

- ↑ Ransford & Kinsey 1979, p. 2.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Ross, Cameron (27 June 2014). "The Siege of Elands River". Australian War Memorial. Retrieved 13 November 2018.

- ↑ Ransford & Kinsey 1979, p. 3.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 Coulthard-Clark 1998, p. 85.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Wilcox 2002, p. 123.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Odgers 1988, p. 41.

- ↑ Ransford & Kinsey 1979, p. 4.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 Wilcox 2002, p. 125.

- 1 2 3 Ransford & Kinsey 1979, p. 7.

- 1 2 Ransford & Kinsey 1979, p. 6.

- ↑ Ransford & Kinsey 1979, pp. 7–8.

- 1 2 Ransford & Kinsey 1979, p. 8.

- ↑ Coulthard-Clark 1998, pp. 84–85.

- ↑ Davitt 1902, p. 443.

- ↑ Jeal 2007, pp. 324–325.

- ↑ Jeal 2007, p. 325.

- ↑ Wilcox 2002, pp. 126–127.

- ↑ Warwick 1983, pp. 41–46.

- 1 2 3 Ransford & Kinsey 1979, p. 9.

- 1 2 3 4 Wilcox 2002, p. 127.

- 1 2 3 Wilcox 2002, p. 128.

- 1 2 3 Horner 2010, p. 67.

- ↑ Wilcox 2002, pp. 125 and 128.

- ↑ Beckett 2018, p. 237.

- ↑ Smith 2004.

- ↑ Pakenham 1992, pp. 523–524.

- ↑ "Spotify". open.spotify.com. Retrieved 21 October 2023.

References

- Beckett, Ian F.W. (2018). A British Profession of Arms: The Politics of Command in the Late Victorian Army. Norman, Oklahoma: University of Oklahoma Press. ISBN 978-0-8061-6171-6.

- Coulthard-Clark, Chris (1998). Where Australians Fought: An Encyclopaedia of Australia's Battles (1st ed.). St Leonards, New South Wales: Allen & Unwin. ISBN 978-1-86448-611-7.

- Davitt, Michael (1902). The Boer Fight For Freedom (1st ed.). New York & London: Funk & Wagnalls. OCLC 457453010.

- Horner, David (2010). Australia's Military History For Dummies. Milton, Queensland: John Wiley & Sons. ISBN 978-1-74216-983-5.

- Jeal, Tim (2007). Baden-Powell: Founder of the Boy Scouts. New Haven, Connecticut: Yale University Press. ISBN 978-0-300-12513-9.

- Odgers, George (1988). Army Australia: An Illustrated History. Frenchs Forest, New South Wales: Child & Associates. ISBN 978-0-86777-061-2.

- Pakenham, Thomas (1992) [1979]. The Boer War. London: Abacus. ISBN 978-0-349-10466-9.

- Ransford, Oliver N.; Kinsey, H.W. (1979). "The Siege of Elands River" (PDF). Rhodesiana. 40 (1). ISSN 0556-9605.

- Smith, R.W. (2004). "Modderfontein: 17 September 1901". Military History Journal. 13 (1). ISSN 0026-4016.

- Warwick, Peter (1983). Black People and the South African War 1899–1902. Cambridge, United Kingdom: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-52125-216-4.

- Wilcox, Craig (2002). Australia's Boer War: The War in South Africa, 1899–1902. Melbourne, Victoria: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-551637-1.

- Wulfsohn, Lionel (1984). "Elands River: A Siege Which Possibly Changed the Course of History in South Africa". Military History Journal. 6 (3). ISSN 0026-4016.