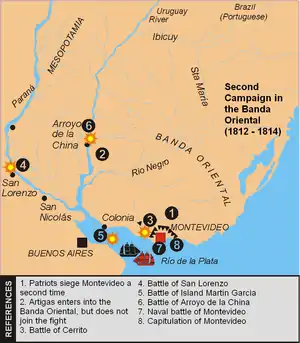

| Battle of Martín García | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the Second Banda Oriental campaign | |||||||

| |||||||

| |||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

|

|

| ||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

| William Brown | Jacinto de Romarate | ||||||

| Strength | |||||||

|

1 frigate 1 corvette 1 brigantine 2 schooners 1 Falucho 1 sloop [91 cannons] 415 sailors and 177 troops.[1] |

2 brigantines 1 brigantine 1 sloop 3 gunboats 1 landing craft and 4 minor vessels [39 cannons (2 in battery)] 430 troops.[1] | ||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||

| One vessel damaged, 23 dead, 35 wounded[1] | One minor vessel captured, 10 dead, 47 prisoners, 17 wounded[1] | ||||||

The Battle of Martín García was fought from 10 to 15 March 1814 between the forces of the United Provinces of the Río de la Plata under the command of then-Lieutenant Colonel Guillermo Brown, and the royalist forces commanded by frigate captain Jacinto de Romarate, defending the region.

After a small naval engagement where the running aground of the leading revolutionary vessel gave the royalists a small victory, but suffering numerous casualties, the United Provinces troops took the island by assault forcing Romarate's squadron to retreat.

Brown's victory divided the enemy's forces, and secured the United Provinces' control of access to the interior waterways, and made possible their advance on Montevideo. After the decisive victory at the Buceo engagement, they could also blockade the city to the open sea completing the land blockade by the army, causing the city's surrender.

The conflict

On 25 May 1810 the May Revolution in Buenos Aires deposed viceroy Baltasar Hidalgo de Cisneros and established a local government known as the Primera Junta. Montevideo, at the eastern side of the Río de La Plata (the Banda Oriental, modern-day Uruguay), did not acknowledge their authority, and recognized instead the Cortes of Cádiz established in Spain. This was resisted in the countryside around Montevideo, and the "Cry of Asencio" began the armed conflicts in the area. Montevideo was soon surrounded and sieged, by the militias under José Gervasio Artigas and Buenos Aires forces under José Rondeau.

Even with the city under siege from land, the royalist naval squadron maintained the naval supremacy over the waterways, the Río de la Plata and the Uruguay and Paraná rivers. The Montevidean squadron under Jacinto de Romarate destroyed the first flotilla from Buenos Aires, which went up the Paraná River carrying reinforcements to the Paraguay campaign, at the Battle of San Nicolás.

After that victory, Montevideo's naval forces could then establish a blockade of the port of Buenos Aires, effect a bombardment and avoid the fall of Montevideo.

After the failure of the armistice signed on 20 October 1811 between the First Triumvirate and the Viceroy Francisco Javier de Elío, on 20 October 1812, a second siege of Montevideo ensued. The tenacity of the defenders and their control of the surrounding rivers, and the lack of means for the attackers to beark this situation kept the front without major changes until 1814.

The dissent between the Buenos Aires troops and the local militias of Artigas, did not help the attacker's situation. Even through this some expeditions were organized by the defenders to break out and obtain supplies, yet they failed, among them by the opposition of José de San Martín at the battle of San Lorenzo, and whatever little they obtained was not enough to cover Montevideo's needs, who suffered hunger and diseases, especially scurvy.

The second squadron

On 5 November 1813, after the resignation of José Julián Pérez, Juan Larrea joined the Second Triumvirate in Buenos Aires, along with Gervasio Antonio de Posadas and Nicolás Rodríguez Peña.

The war situation was dire. General Manuel Belgrano was retreating to La Quiaca in the north, after the defeats at Vilcapugio and Ayohuma, Patria Vieja in Chile was being invaded by the forces of the Lima and due to internal conflicts was approaching the Disaster of Rancagua. Montevideo had an army bigger in numbers than the army that encircled them and there was no prospects of surrender as they controlled the access through the rivers and the sea and Artigas was joining a civil war by promoting the defection of the Argentine provinces of Entre Ríos and Corrientes.

Larrea started to consider the formation of a new squadron to force the situation in the eastern front, but it was quickly learned that this was not possible. There were no naval forces in the provinces. They only had one sloop and the port's landing craft. The arsenal only had 30 cannons and carronades of different calibers and almost useless due to age and lack of maintenance, a few rifles and less than 200 quintals of gunpowder. Their warehouses lacked wood, tar, canvas, rope and marine tools. There was no trained personnel nor protocols for the recruiting and instruction of officers, sailors nor Marines. Finally, the treasury only had a thousand pesos, customs resources were minimal due to the blockade and credit was exhausted.

Larrea chose to promote an agreement with Guillermo Pío White, a wealthy American merchant native of Boston who was sympathetic to the revolutionary cause, who would front the funds necessary to finance the acquisition of vessels and equipment, with a promise of later compensation, tied to the success of the enterprise. On 28 December 1813 anm agreement was signed between the Triumvirate and White.

At the beginning of 1814 the executive power was concentrated on the Supreme Director of the United Provinces of the Río de la Plata. Gervasio Antonio Posadas was named Supreme Director and Juan Larrea was named Economy Minister, which then maintained the agreement with White alive.

In only two months, a small squadron was formed and a crew readied, composed mostly by foreigners in officers and men, while the embarked troops were composed of locals.

The question of who would be in command generated a strong debate. The principal candidates were the American lieutenant colonel Benjamin Franklin Seaver, commander of the schooner Juliet, who was supported by his compatriot Pío White, the corsair Estanislao Courrande, who since 1803 harassed British commerce with corsair raids, and lastly the Irish Guillermo Brown.

Command was finally given to Brown, including Pío White's vote, in part for his strength of character, (all candidates had the necessary experience), but also because of his charisma over the commanders and sailors, most of them Irish, British or Scots.

Previous encounters

On 7 July 1813 a group of thirteen revolutionary soldiers under the command of lieutenant José Caparrós made a surprise and successful incursion in Martín García Island, at the time in royalists hands, and defended by 70 men.

The Río de la Plata was difficult to navigate due to the extensive sand banks which reduced navigation to small draft vessels forcing the use of the few existing open channels, subject to frequent changes due to sediment accumulation and the changing winds. Martín García island, controls the west channel, which due to its relative depth was the obligatory path for any vessel with a draft of no more than 2 or 3 meters, who wanted to reach the interior rivers flowing into the Río de la Plata, such as the Paraná or the Uruguay rivers, closed to the west by an extensive sand bank.

Facing the risk of losing control of the strategic island, and with the objective of gaining a base from which to attack the town of Colonia del Sacramento, occupied by the rebels, at the beginning of 1814 Romarate fortified the island and parked a flotilla of 9 vessels with 18 and 24 pounder artillery pieces.

Alarmed by the news of the formation of this new Buenos Aires fleet, it was proposed in Montevideo to attack Buenos Aires before it would become operational, but the speed of its formation thwarted the plan and had to be abandoned.

On the revolutionary side, after receiving his commission as commander, lieutenant colonel Brown started his campaign by sailing his small new fleet to Colonia del Sacramento (in today's Uruguay).

The battle

The opposing forces

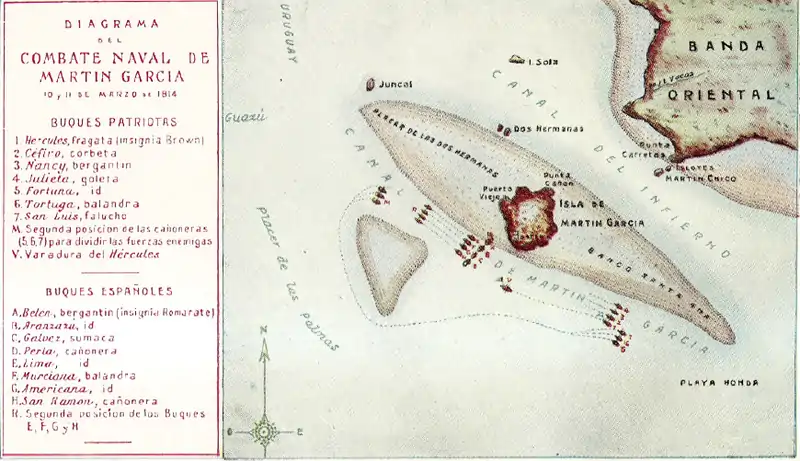

The patriot forces had a merchant frigate named Hércules (350 tons), the corvette Zephyr, (220 tons), brigantine Nancy (120 tons), schooner Juliet (150 tons), schooner Fortuna (90 tons), landing boat San Luis (15 tons), and sloop Nuestra Señora del Carmen (48 tons).[2]

The royalist squadron was composed of the brigantines Belén (220 tons), Nuestra Señora de Aránzazu (181 tons), and Gálvez (90 tons), sloops Americana (60 tons) and Murciana (115 tons), gunboats Perla, Lima, and San Ramón (30 tons), plus four small support vessels.

Even though the number of vessels was in parity, the total of guns favored the rebel navy. With 91 cannons, 430 sailors and 234 troops in front of the 36 cannons (2 in a land battery) and 442 men of the royalists, the advantage was supposedly on the revolutionary side. Nonetheless, as a third of the force was concentrated on the lead ship Hércules, so the advantage was tied to its performance and luck.

Battle disposition

On the 8th Brown, in front of the town of Colonia with Hércules, Fortuna, San Luis and Carmen, saw three royalist brigantines to the northwest. He followed them until dusk, when having verified they were entering the Martín García channel and going to the island, he turned to Buenos Aires to look for reinforcements.

That same day at 8:00 pm the royalist squadron raised anchor at Martín García, to the west of the island. Romarate formed his ships in an east–west line, covering the channel from the anchorage in a semicircle, supported from land by a battery of two cannons and gunfire from the island's troops under midshipman José Benito de Azcuénaga.[3]

On the 9th at 2:00 pm Brown joined with Zhepyr, Juliet and Nancy, then turned towards Martín García to meet the enemy. At 5:00pm the rebel squadron anchored on the channel about four leagues to the southwest of the royalists, with the Santa Ana bank to starboard. The 10th in the morning they raised sail on a light southeast wind converging to Romarate through both channels.

Brown's plan was attacking through the front and rear of the Spanish. he detached a division composed of Fortuna, Carmen and San Luis to go around the sandbank to the west to have it at its back and the royalists in his front while the principal force attacked the royalists front. Hércules was on the left, then Zephyr, Nancy and Juliet on the right.

The encounter

The attack was not simultaneous. At 1:30 pm, when the encirclement was not yet complete, Brown's squadron, with Juliet in front opened fire over the royalists which was immediately returned.

The Argentine lead ship attempted to advance under fire, but having lost her pilot, she got stuck on a sand bank on the west of the island, under fire and bows-on to the enemy, suffering sustained fire and not being able to return it, directing their broadsides to the land batteries. Brown questioned the way in which the rest of the squadron "conducted themselves during the action, even though having sent all the signals and having gone personally on my boat before midnight the night before and requested their support, all of which was in vain".

Having secured the front, Romarate sent the sloops Americana and Murciana, to the gunboat Perla and the Salvador's launch to confront the revolutionary division deployed on the north channel, which after a light exchange of fire retreated and joined the rest of the squadron. Combat continued until sundown, with Hércules taking the worst part.[4]

In this first and most bloodiest first day of the Combate of Martín García, Romarate successfully repelled the enemy's attack. They had 45 dead and 50 wounded and the attacking force's losses were high. Rebel Commanders Benjamin Seaver and Elias Smith, and also the chief of the embarked troops, the French captain Martín de Jaume, second lieutenant Robert Stacy, midshipman Edward Price, sailors Richard Brook and William Russell and cook Peter Brown were among the casualties.

Bernard Campbell, the chief surgeon, had very difficult moments having to treat the wounded with inadequate means. Among the wounded there were valet Tomas Richard and sailors James Stone, Henry Harris, Elsey Miller and Anthony O’Donnell.[5]

At dawn on the 11th, fire recommenced at 8:45am, when finally Hércules with her sails and masts destroyed and with 82 impacts on the vessel finally loosened the grip of the sand bar with the tide and with only one sail left, could leave the channel and retreat by the Las Palmas sand bank.

At 5:00 pm on that day Romarate sent a note to the commander of the Montevideo garrison Miguel de la Sierra, informing he had few casualties, four dead and seven wounded, he had disembarked on the island and judged that given the losses suffered, as soon as the patriot fleet was in condition it would retreat to Buenos Aires, so he asked his commander for more powder and ammunition in all calibers, and urgent reinforcements to annihilate them before they could seek refuge in port.

If Your Excellency has expulsed from that port as I believe, Mercurio, Paloma, Hiena and Cisne, and they are near the islands of Hornos or Valizas, they are lost to the forces of Buenos Aires, and if not, their absence would be very painful in this critical situation.

— Romarate's Notes, Carranza.

Awaiting reinforcements Romarate disembarked two cannons under the command of ensign Francisco Paloma to reinforce the land forces. The commander of the land forces, José Benito de Azcuénaga, agreed with Romarate:

if they return I think they have been chastised to not again insult the national forces.

— de Azcuénaga in Romarate's Notes, Carranza - cited work - page 228

.

Nonetheless Romarate had made a bad judgment. On the one side the Spanish squadron under frigate captain José Primo de Rivera y Ortiz de Pinedo was negligent and had not positioned his fores in case he would be required as defensive reinforcements, be it in the case of defeat, as support or victory, and the measures to be taken after Romarate's order was known were so lax that Romarate never received reinforcements nor supplies.

Also in contrast to what Romarate supposed, and showing in his adversary a completely different way of thinking, after the repairs done to Hércules

We installed lead plates below the waterline and covered her with leather hides and tar, which changed her nickname to The Black Frigate

and counting only with few reinforcements, 23 Dragoons and 23 marines from the 6th Regiment, with their officers, respectively Dragoon Ensign Gervasio Espinosa and sub-lieutenant Luis Antonio Frutos sent in the schooner Hope[6] by the Commander of Colonia del Sacramento, Vicente Lima, under first lieutenant of the Buenos Aires Dragoon Regiment Pedro Oroná, and 17 militias from the town of Las Conchas, Brown resumed the attack.

The assault

Incapable of confronting the enemy head-on again, the Argentine commander changed his strategy. With the few reinforcements received he had an infantry force superior to the one defending the island. If he could attack by surprise and with sufficient speed before Romarate could disembark his troops and change the balance of forces, it was feasible to conquer the garrison.

With a lack of non-commissioned officers they decided to have the commanders meet to plan and coordinate the attack. Lieutenant Oroná was selected to command and decided to divide his forces in three divisions if 80 men. The first division was put under command of Regiment #2 Lieutenant Manuel José Balbastro, with his second in command Dragoon Ensign Gervasio Espinosa. The second was put under Regiment #2 lieutenant Manuel Castañer and 6th Regiment sub-lieutenant Luis Antonio Frutos, and the third under army lieutenant Jaime Kainey with Grenadiers sub-lieutenant Mariano Antonio Durán.

At 8:00 pm on the 14th they anchored silently a half-mile to the southeast near Puerto Viejo and at 02:30 am on the 15th they disembarked 240 men in 20 minutes, using 8 launches. Upon getting near the coast they received fire from a few enemy soldiers hiding in the bush who when fire was returned they scampered to the interior of the island.

With the landing secure, Brown took the squadron towards the royalists ships to simulate an attack as a diversion from the principal effort. The advance over land was detected and when climbing a hill overlooking the port they were fired upon by royalist troops. At the moment this attack was seen Brown's fleet started a cannonade from the west over the royalist squadron.

The attack, under enemy fire and in the run on a rough and ascending path, briefly stalled. In that critical moment they ordered the drum and bugle to play the Saint Patrick’s Day in the Morning march. The troops were composed of different nationalities with the majority being Irish, so this known piece, played a few days before Saint Patrick's Day, raised the attackers' morale. The song became the first naval march of Argentina.[7]

Because of this event this song was made the official march of the island and was officially added to the Argentine Navy's repertoire in 1977. The troop's advance was renewed with great strength attacking the fort with bayonets. The Spaniards were overwhelmed and surrendered after about 20 minutes of combat, where lieutenant Jones of the Zhepyr captured the land battery, turned the cannons against the royalist ships and raised the United Provinces flag on the island. The victory was certified much later at the signing of the Treaty of the Río de la Plata and it Maritime Front.[8]

The royalists had 10 dead, 7 wounded and 50 prisoners. The attackers casualties were three soldiers dead and five wounded. The commander of the force lieutenant Pedro Oroná and sub-lieutenant Pedro Aguilar were lightly wounded.[9]

Romarate, lacking powder and ammunition had to remain on the side as witness to the enemy victory. The last skirmish was held on the dawn of the 15th when the sloop Carmen under Commander Spiro who had approached to spy in the night, run a few volleys of musket fire towards the enemy.

In a terse note, Brown communicated to Government Minister Larrea

...that Martín García island was taken by the forces of land and sea under my command, on last Monday at four thirty at night ...I plead you write detailing how should I dispose of the island and its naval force.

Only when in front of Montevideo, on 19 April the same year, he would extend on the details of the action and casualties suffered.

In that, his definitive combat report, Brown listed some of the casualties in the Hércules on the 10th and 11th. From officers and sailors: Captain Elias Smith, Third Lieutenant Robert Stacy, helmsman Antonio Castro, cabin boy Eduardo Price, first class sailors Ricardo Brook and Guillermo Russell, second class Francisco Guevara, Salomón Lyon, Felipe Rico, Lázaro Molina and Joaquín Uraqui, and cook Pedro Brown. Troops: Captain Jaime Martín de Jaume and soldiers Tomás Felisa, José Antonio Balija, José Herrera, Silvestre Murúa, Juan Olivera, Marcos Ávila, José Antonio Tolosa, José González.[10]

Consequences

Not having received the supplies and reinforcements he requested, and knowing of the help promised by Fernando Otorgués, second of José Gervasio Artigas, who before the imminence of the end of the siege of Montevideo, which they had abandoned at the beginning of the year and confronted Carlos María de Alvear, Romarate took advantage of the winds which have veered from the southeast incrementing the rising tide, to escape by the sand banks, and was forced to hide by the end of the Uruguay River.

On the 25th following Larrea's orders, the prisoners were embarked, the houses on the island burned, and the remaining population evacuated. The squadron raised anchor and sailed, arriving on the 26th in Colonia, were the prisoners debarked. Brown, ignoring the orders from his superiors to chase Romarate, only detached a small division after him, supposing that Romarate was lacking powder and ammunition (which was true until the supplies came from Otorgués) and it was enough to assure his isolation; while the bulk of the naval squadron went to what he considered the big prize, the annihilation of the squadron defending Montevideo and taking the city.

The Battle of Martín García was then the beginning of a campaign of 100 days which led by Brown ended Spain's naval power in the Río de la Plata and forced the surrender of their last bastion in Montevideo.

References

- 1 2 3 4 Camogli, p. 314

- ↑ Arguindeguy, Pablo E. CL, and Rodríguez, Horacio CL; "Buques de la marina Argentina 1810-1852 sus comandos y operaciones" (in Spanish)

- ↑ Romarate's notes, in Angel Justiniano Carranza's, Campañas Navales de la República Argentina, Volume III - Notes to Vol 1 and 2, (in Spanish) Secretaria de Estado de Marina, 1962.

- ↑ Romarate's Notes, Carranza, cited work (in Spanish)

- ↑ Combate de Martín García (in Spanish), lagazeta.com.ar

- ↑ Justiniano Carranza, Campañas navales de la República argentina, volume 2, pages 73 and 224.

- ↑ Ruiz Moreno, Isidoro J. (1998). La Marina Revolucionaria. Planeta, p. 23. ISBN 950-742-917-4

- ↑ lagazeta.com.ar

- ↑ Report from Pedro Oroná, 18 March 1814, Carranza.

- ↑ Carranza, Ángel Justiniano, Campañas Navales de la República Argentina, Volume III, pg 224 (in Spanish)

Bibliography

- Carranza, Angel Justiniano; Luciano de Privitellio (1962). Campañas Navales de la República Argentina, Volume I - Books 1 and 2 (in Spanish). Buenos Aires: Secretaria de Estado de Marina.

- Carranza, Angel Justiniano, Campañas Navales de la República Argentina, Volume III - Notes to Books 1 and 2, Secretaria de Estado de Marina, 1962 (in Spanish)

- Arguindeguy, Pablo E. CL, y Rodríguez, Horacio CL; Buques de la Marina Argentina 1810-1852 sus comandos y operaciones, Buenos Aires, Instituto Nacional Browniano, 1999 (in Spanish)

- Castagnin, Daniel Ítalo, Visión estratégica del teatro de operaciones platense (1814-1828), Revista del Mar # 162, Instituto Nacional Browniano, 2007 (in Spanish)

- Arguindeguy, Pablo E. Apuntes sobre los buques de la Marina Argentina (1810–1970) -Tomo I, 1972 (in Spanish)

- Memorias del Almirante Guillermo Brown sobre las operaciones navales de la Escuadra Argentina de 1814-1828, Biblioteca del Oficial de Marina, Vol. XXI, 1936, Buenos Aires, Argentina (in Spanish)

- Piccirilli, Ricardo y Gianello, Leoncio, Biografías Navales, Secretaría de Estado de Marina, Buenos Aires, 1963 (in Spanish)

- Camogli, Pablo; Luciano de Privitellio (2005). Batallas por la Libertad (in Spanish). Buenos Aires: Aguilar. ISBN 987-04-0105-8.

External links

- Navíos de las Provincias Unidas del Río de la Plata (in Spanish)

- Historical Handbook of World Navies

- Argentine Navy official site (in Spanish)

- Hércules (Frigate) (in Spanish)

- Isla Martín García. (in Spanish)