| Battle of Saipan | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

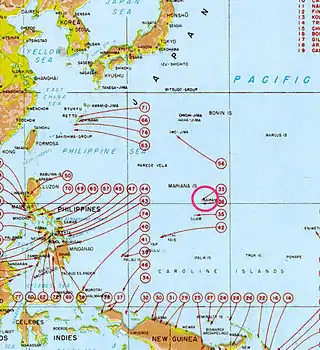

| Part of the Mariana and Palau Islands campaign of the Pacific Theater (World War II) | |||||||

.jpg.webp) LVTs heading for shore on 15 June 1944. Birmingham in foreground; the cruiser firing in the distance is Indianapolis. | |||||||

| |||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

|

|

| ||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

|

Richmond K. Turner Holland Smith |

Yoshitsugu Saitō † Chūichi Nagumo † Takeo Takagi † Matsuji Ijuin † | ||||||

| Units involved | |||||||

| V Amphibious Corps | 31st Army | ||||||

| Strength | |||||||

|

Assault: 71,034 Garrison: 23,616 Total: 94,650[1] |

Army: 25,469 Navy: 6,160 Total: 31,629[2] | ||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||

|

Land forces:[3][4] 3,100–3,225 killed 326 missing 13,061–13,099 wounded Ships personnel:[5] 51+ killed 32+ missing 184+ wounded |

25,144+ dead (buried as of 15 August) 1,810 prisoners (as of 10 August) Remaining ~5,000 committed suicide, killed/captured later, or holding out[6] | ||||||

| 8,000[7]–10,000[8] civilian deaths | |||||||

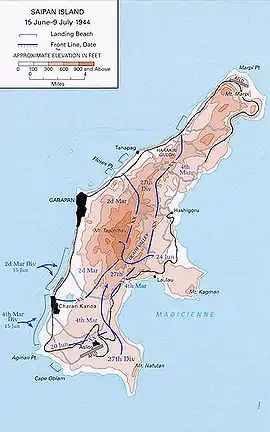

The Battle of Saipan was a battle of the Pacific campaign of World War II, fought on the island of Saipan in the Mariana Islands from 15 June to 9 July 1944 as part of Operation Forager. It has been referred to as the "Pacific D-Day" with the invasion fleet departing Pearl Harbor on 5 June 1944, the day before Operation Overlord in Europe was launched, launching nine days later. The U.S. 2nd Marine Division, 4th Marine Division, and the Army's 27th Infantry Division, commanded by Lieutenant General Holland Smith, defeated the 43rd Infantry Division of the Imperial Japanese Army, commanded by Lieutenant General Yoshitsugu Saitō. The loss of Saipan, with the deaths of at least 29,000 troops and heavy civilian casualties, precipitated the resignation of Prime Minister of Japan Hideki Tōjō and left the Japanese archipelago within the range of United States Army Air Forces B-29 bombers.

Background

American strategic decisions

In the campaigns of 1943 and the first half of 1944, the Allies had captured the Solomon Islands, the Gilbert Islands, the Marshall Islands and the Papuan Peninsula of New Guinea. This left the Japanese holding the Philippines, the Caroline Islands, the Palau Islands, and the Mariana Islands.

The Mariana Islands had not been a key part of pre-war American planning (War Plans Orange and Rainbow) because the islands were well north of a direct sea route between Hawaii and the Philippines. At the time, naval air/sea/logistics ability were not envisioned as being able to support operations against a place so far from potential land-based support. But by early 1943 Admiral Ernest King, Commander in Chief of the United States Fleet, had become increasingly convinced of the strategic location of the islands as a base for submarine operations and air facilities for Boeing B-29 Superfortress bombing of the Japanese home islands.[9] From these latter bases, communications between Japan and Japanese forces to the south and west could be cut. From the Marianas, Japan would be well within the range of an air offensive relying on the new B-29 with its operational radius of 3,250 mi (5,230 km).

The capture of the Marianas was formally endorsed in the Cairo Conference of November 1943. The plan had the support of U.S. Army Air Force planners because the airfields on Saipan were large enough to support B-29 operations, within range of the Japanese home islands, and unlike a China-based alternative, was not open to Japanese counter-attacks once the islands were secure. However, General Douglas MacArthur strenuously objected to any plan that would delay his return to the Philippines. His objections were routed through formal channels as well as bypassing the Joint Chiefs of Staff, appealing directly to Secretary of War Henry Stimson and President Franklin D. Roosevelt.[10]

MacArthur's objections were not without tactical reasoning based on the experience of the invasion of Tarawa but were voiced before the vastly improved experience in the Gilbert and Marshall Islands campaign, the increase in naval forces, the successful attack on Truk and the Caroline Islands by carrier-based aircraft, and coordinated armed services experience gained by all these operations in Admiral Chester W. Nimitz’s Pacific Ocean Area of operations.[11]

While not part of the original American plan, MacArthur, Commander of the South West Pacific Area, obtained authorization to advance through New Guinea and Morotai toward the Philippines. This allowed MacArthur to keep his personal pledge to liberate the Philippines, made in his "I shall return" speech, and also allowed the active use of the large forces built up in the southwest Pacific theatre. The Japanese, expecting an attack somewhere on their perimeter, thought an attack on the Caroline Islands most likely. To reinforce and supply their garrisons, they needed naval and air superiority, so Operation A-Go, a major carrier attack, was prepared for June 1944.[12]

Island geography and Japanese defenses

Unlike the small, flat coral atolls of the Gilberts and Marianas,[13] Saipan were volcanic islands with diverse terrain well suited for defense.[14] It is an island of about 47 square miles,[15][lower-alpha 1] which has a volcanic core surrounded by limestone. In the center of the island is Mount Tapochau, which rises to 1,554 ft. From the mountain, a high ridge ran northward about seven miles to Mount Marpi.[18] This area was filled with caves and ravines concealed by forest and brush.[19]

The southern half of the island was flatter, but covered with sugar cane fields.[20] After the Japanese government had taken over Saipan from Germany in 1914, the island became focused on sugar production.[21] Seventy percent of Saipan's acreage was dedicated to sugar cane,[22] It was so plentiful that a narrow-gauge rail was built around the perimeter of the island to facilitate its transportation.[23] These cane fields an obstacle: they were difficult to maneuver in and provided concealment for the defenders.[24]

Saipan was the first island of the war where the United States forces encountered a substantial Japanese civilian population,[25] and the first where U. S. Marines had to engage in house-to-house urban combat.[26] Approximately 26,000[7] to 28,000[8] civilians lived on the island primarily serving the sugar industry.[22] The majority of them were Japanese subjects, most of whom were from Okinawa and Korea; a few were Chamorro people.[23] The largest towns on the island–the administrative center of Garapan with its population of 10,000, Charan Kanoa, and Tanapag– were on the western coast of the island, which was where the best landing beaches for an invasion were.[24]

The Japanese defenses were set up to defeat an invading force at the beaches, when the invading troops were most vulnerable.[27]. These defenses focused this defense on the most likely invasion location, the western beaches south of Garapan. [28] The original plans called for a defense in depth that fortified the entire island[29] if time allowed.[30], but the Japanese were unable to build their defense by the time of the invasion. Much of the building material sent to Saipan, such as concrete and steel, had been sunk in transit by American submarines,[13] and the timing of the invasion surprised the Japanese, who believed they had until November to complete their defense.[31] As of June, many fortifications remained incomplete, available building materials were left unused, and many artillery guns were not properly deployed.[32] This made the defenses vulnerable, if an invading force broke through the beach defenses, the Japanese troops would have to rely on Saipan's rough terrain, especially its caves, for protection.[31]

Opposing forces

United States

US Fifth Fleet

Admiral Raymond A. Spruance

- Northern Attack Force (Task Force 52)

- Vice Admiral Richmond Kelly Turner

- Expeditionary Troops (Task Force 56)

- Lieut. General Holland M. Smith, USMC

- Approx. 59,800 officers and enlisted

- V Amphibious Corps (Lt. Gen. Smith)

- 2nd Marine Division (Maj. Gen. Thomas E. Watson, USMC)

- 4th Marine Division (Maj. Gen. Harry Schmidt, USMC)

- 27th Infantry Division (Army) (Maj. Gen. Ralph C. Smith, USA)

- V Amphibious Corps (Lt. Gen. Smith)

Japan

Central Pacific Area Fleet HQ

Vice Admiral Chūichi Nagumo[lower-alpha 2]

- Thirty-first Army

- Lieut. General Hideyoshi Obata[lower-alpha 3]

- Defenses of Saipan

- Lieut. General Yoshitsugu Saitō[lower-alpha 4]

- Approx. 25,500 army and 6,200 navy personnel

- 43rd Division

- 47th Independent Mixed Brigade

- Miscellaneous units

Battle

The bombardment of Saipan began on 13 June 1944 with seven fast battleships, 11 destroyers and 10 fast minesweepers under Vice Admiral Willis A. Lee Jr. The battleships delivered 2,400 16 in (410 mm) shells, but to avoid potential minefields, fire was from a distance of 10,000 yd (9,100 m) or more and crews were inexperienced in shore bombardment. The following day, two naval bombardment groups led by Rear Admiral Jesse B. Oldendorf arrived off the shore of Saipan. This force was the main naval fire support for the seizure of the island and consisted of 7 dreadnoughts, 11 cruisers, and 26 destroyers, along with destroyer transports and fast minesweepers. The dreadnoughts, commissioned between 1915 and 1921, were trained in shore bombardment and were able to move into closer range. Four of them (California, Pennsylvania, Maryland and Tennessee) were survivors of the attack on Pearl Harbor.[33]

The landings[34] began at 07:00 on 15 June 1944. More than 300 LVTs landed 8,000 Marines on the west coast of Saipan by about 09:00. Eleven fire support ships covered the Marine landings. The naval force consisted of the battleships Tennessee and California, the cruisers Birmingham and Indianapolis, the destroyers Norman Scott, Monssen, Coghlan, Halsey Powell, Bailey, Robinson, and Albert W. Grant. Careful artillery preparation—placing flags in the lagoon to indicate the range—allowed the Japanese to destroy about 20 amphibious tanks, and they had placed barbed wire, artillery, machine gun emplacements, and trenches to maximize the American casualties. However, by nightfall, the 2nd and 4th Marine Divisions had a beachhead about 6 mi (10 km) wide and 0.5 mi (1 km) deep.[35] The Japanese counter-attacked at night but were repelled with heavy losses. On 16 June units of the 27th Infantry Division landed and advanced on the airfield at Ås Lito. Again the Japanese counter-attacked at night. On 18 June Saito abandoned the airfield.

The invasion surprised the Japanese high command, which had been expecting an attack further south. Admiral Shigetarō Shimada, Commander in Chief of the Imperial Japanese Navy (IJN), saw an opportunity to use the A-Go force to attack the U.S. Navy forces around Saipan. On 15 June he gave the order to attack. But the resulting Battle of the Philippine Sea was a disaster for the IJN, which lost three aircraft carriers and hundreds of planes.

Without resupply, the battle on Saipan was hopeless for the defenders, but the Japanese were determined to fight to the last man. Saitō organized his troops into a line anchored on Mount Tapochau in the defensible mountainous terrain of central Saipan. The nicknames given by the Americans to the features of the battle—"Hell's Pocket", "Purple Heart Ridge" and "Death Valley"—indicate the severity of the fighting. The Japanese used many caves in the volcanic landscape to delay the attackers, by hiding during the day and making sorties at night. The Americans gradually developed tactics for clearing the caves by using flamethrower teams supported by artillery and machine guns.

The operation was marred by inter-service controversy when Marine General Holland Smith, dissatisfied with the performance of the 27th Division, relieved its commander, Army Major General Ralph C. Smith. However, Holland Smith had not inspected the terrain over which the 27th was to advance. Essentially, it was a valley surrounded by hills and cliffs under Japanese control. The 27th took heavy casualties and eventually, under a plan developed by Smith and implemented after his relief, had one battalion hold the area while two other battalions successfully flanked the Japanese.[36]

By 6 July the Japanese had nowhere to retreat. Saitō made plans for a final suicidal banzai charge. On the fate of the remaining civilians on the island, Saito said, "There is no longer any distinction between civilians and troops. It would be better for them to join in the attack with bamboo spears than be captured."[37] At dawn of 7 July with a group of 12 men carrying a red flag in the lead, the remaining able-bodied troops — about 4,000 men — charged forward in the final attack. Behind them came the wounded, with bandaged heads, crutches, and barely armed. The Japanese surged over the American front lines, engaging both Army and Marine units. The 1st and 2nd Battalions of the 105th Infantry Regiment were almost destroyed, losing well over 650 killed and wounded. The two battalions fought back, as did the Headquarters Company, 105th Infantry, and supply elements of 3rd Battalion, 10th Marine Artillery Regiment, resulting in over 4,300 Japanese killed and over 400 dead US soldiers with more than 500 more wounded. The attack on 7 July would be the largest Japanese banzai charge in the Pacific War.[38]

By 16:15 on 9 July, Turner announced that Saipan was officially secured.[39] Saitō, along with commanders Hirakushi and Igeta, committed suicide in a cave. Vice Admiral Chuichi Nagumo, the naval commander who led the Japanese carriers at Pearl Harbor, also committed suicide in the closing stages of the battle. He had been in command of the Japanese naval air forces stationed on the island.

In the end, almost the entire garrison of troops on the island—at least 29,000—died. For the Americans, the victory was the most costly to date in the Pacific War: out of 71,000 who landed, 2,949 were killed and 10,464 wounded.[40][41]

Smith and V Amphibious Corps (VAC) anticipated that taking Saipan would be difficult, and they wanted to have a mechanized flamethrowing capability. Research, development, and procurement made that a long-term prospect. So VAC purchased 30 Canadian Ronson flamethrowers and requested that the Army's Chemical Warfare Service (CWS) in Hawaii install them in M3 Stuarts, and termed them M3 Satans. Seabees with the CWS had 24 ready for the battle.

Aftermath

With the capture of Saipan, the American military was only 1,300 mi (1,100 nmi; 2,100 km) away from the home islands of Japan. Holland Smith said: "It was the decisive battle of the Pacific offensive [...] it opened the way to the [Japanese] home islands."[42] The victory would prove to be one of the most important strategic moments during the war in the Pacific Theater, as the Japanese archipelago was now within striking distance of United States' B-29 bombers.[43] From this point on, Saipan would become the launch point for retaking other islands in the Mariana chain and the invasion of the Philippines in October 1944. Four months after capture, more than 100 B-29s from Saipan's Isely Field were regularly attacking the Philippines, the Ryukyu Islands and the Japanese mainland. In response, Japanese aircraft attacked Saipan and Tinian on several occasions between November 1944 and January 1945. The U.S. capture of Iwo Jima (19 February – 26 March 1945) ended further Japanese air attacks.

The loss of Saipan brought the collapse of Prime Minister of Japan Hideki Tōjō's cabinet. Emperor Hirohito, who was disappointed with the progress of the war, withdrew his support of Tōjō, who resigned on 18 July. [44] He was replaced by former IJA General Kuniaki Koiso, who was a less capable leader.[45] In July, the Chief of the War Guidance department of the Imperial General Headquarters, Colonel Sei Matsutani,[46] drafted a report to the Army General Staff that after Saipan Japan had "no future prospect of reversing the general situation of the war."[47] After the war, Vice Admiral Shigeyoshi Miwa stated "Our war was lost with the loss of Saipan"[48] Fleet Admiral Osami Nagano also stated that Saipan was the decisive battle of the war, saying "When we lost Saipan, Hell is [up]on us."[49]

Saipan also saw a change in the way Japanese war reporting was presented on the home front. Initially as the battle started, Japanese accounts concentrated on the fighting spirit of the IJA and the heavy casualties it was inflicting on American forces. However, any reader familiar with Saipan's geography would have known from the chronology of engagements that the U.S. forces were relentlessly advancing northwards. No further mention of Saipan was made following the final battle on 7 July, which was not initially reported to the public.[50] However, after Tōjō's resignation on 18 July, an accurate, almost day-by-day account of the defeat on Saipan was published jointly by the army and navy. This was the first time Japanese forces had accurately been depicted in a battle since Midway. It mentioned the defender's use of use of "human bullets", people who attempted to blow up the enemy by wearing strapped explosives, as well as the near total loss of all Japanese soldiers and civilians on the island. The reports had a devastating effect on Japanese opinion; mass suicides were now seen as defeat.[51]

Further resistance

While the battle officially ended on 9 July, Japanese resistance still persisted with a group of about 50 men lead by Captain Sakae Ōba who survived after the last banzai charge.[52] After the battle, Oba and his soldiers led many civilians through the jungle to escape capture by the Americans, while also conducting guerrilla-style attacks on pursuing forces. The Americans tried numerous times to hunt them down but failed. In September 1944, the Marines began conducting patrols in the island's interior, searching for survivors who were raiding their camp for supplies.[53] Oba's primary goal was self-preservation, but his resistance was so successful, he earned the nickname "the Fox".[52] Oba's holdout lasted for approximately 16 months before finally surrendering on 1 December 1945, three months after the official surrender of Japan.[54][53]

Civilian casualties

Of the approximately 28,000 Japanese, Korean and Chamorro civilians who lived on Saipan at the time of the attack,[55] it is estimated that 8,000[7] to 10,000[8] died as a result of the battle. Many died from the bombing, shelling and cross-fire.[56] Others died because they hid in caves and shelters that were indistinguishable from Japanese combat positions, which the Marines typically destroyed with explosives, grenades and flamethrowers.[57] An unknown number of civilians committed suicide. Some were driven by fear spread by Japanese propaganda that Americans would rape, torture and kill them; others were coerced.[58] Approximately 1,000 civilians committed suicide in the last days of the battle,[59] jumping from places that would become known as "Suicide Cliff" and "Banzai Cliff".[60]

Memorial

Suicide Cliff and Banzai Cliff, along with surviving isolated Japanese fortifications, are recognized as historic sites on the U.S. National Register of Historic Places. The cliffs are also part of the National Historic Landmark District Landing Beaches; Aslito/Isley Field; & Marpi Point, Saipan Island, which also includes the American landing beaches, the B-29 runways of Isley Field, and the surviving Japanese infrastructure of the Aslito and Marpi Point airfields.[61] The American Memorial Park commemorates the American and Mariana people who died during the Mariana Islands campaign.[62] The Central Pacific War Memorial Monument is dedicated to the memory of the Japanese soldiers and civilians who died.[63]

See also

Footnotes

- ↑ Post-war estimates range from 46[16] square miles to 48.[17] Hallas 2019, p. 479, fn 5 points out that most historians describing the battle state that the island is substantially larger. For example, McManus 2021, p. 339, Shaw, Nalty & Turnbladh 1966, p. 238 state that it is 72, Goldberg 2007, p. 38 says 75, and both Brooks 2005, p. 133 and Crowl 1993, p. 29 say 85 square miles.

- ↑ Died by self-inflicted gunshot, 6 July

- ↑ Died by seppuku on Guam, 11 August

- ↑ Died by seppuku, 7 July

Notes

- ↑ "Report on Capture of the Marianas" p. 6. Retrieved 2/12/23. Report compiled 25 August 1944.

- ↑ "Campaign in the Marianas" Appendix C. Retrieved 2/12/23

- ↑ "Report on Capture of the Marianas" Enclosure K part B. 3,100 killed, 326 missing, 13,099 wounded; total cumulative to D+46.

- ↑ "Breaching the Marianas: the Battle for Saipan." Marines in World War II Commemorative Series. Retrieved 2/12/23. 3,225 killed, 326 missing, 13,061 wounded.

- ↑ "Report on Capture of the Marianas" Enclosure K part D. These figures are incomplete since data could not be obtained from all ships.

- ↑ "The Campaign in the Marianas" Annex 3 to Enclosure A

- 1 2 3 AMP 2021.

- 1 2 3 Astroth 2019, p. 166.

- ↑ Toll 2015, p. 436.

- ↑ Toll 2015, pp. 438–439.

- ↑ Toll 2015, pp. 440–441.

- ↑ Morison 1981, p. 221.

- 1 2 Crowl 1993, p. 62.

- ↑ Crowl 1993, p. 29; Goldberg 2007, p. 30.

- ↑ Hallas 2019, p. 11.

- ↑ USACE 2022, p. 3.

- ↑ USGS 1956, p. 1.

- ↑ Crowl 1993, p. 29; Shaw, Nalty & Turnbladh 1966, p. 238.

- ↑ Goldberg 2007, p. 30.

- ↑ Shaw, Nalty & Turnbladh 1966, p. 238.

- ↑ Hoffman 1950, p. 7; Morison 1981, p. 151.

- 1 2 Hallas 2019, p. 7.

- 1 2 Astroth 2019, p. 38.

- 1 2 Lacey 2013, p. 129.

- ↑ Sheeks 1945, p. 112; Toll 2015, p. 508.

- ↑ Hallas 2019, p. vii.

- ↑ Crowl 1993, pp. 62–63.

- ↑ McManus 2021, p. 339–340.

- ↑ Lacey 2013, p. 139.

- ↑ Hallas 2019, p. 57.

- 1 2 Lacey 2013, p. 139.

- ↑ Goldberg 2007, p. 35.

- ↑ "U.S. Army in World War II: Campaign in the Marianas, Ch. 5". United States Army Center of Military History. Retrieved 13 October 2006.

- ↑ Video: Allies Liberate Island of Elba Etc. (1944). Universal Newsreel. 1944. Retrieved 21 February 2012.

- ↑ "Selected June Dates of Marine Corps Historical Significance". This Month in History. History Division, United States Marine Corps. Archived from the original on 31 October 2006. Retrieved 7 June 2006.

- ↑ Goldberg 2007, pp. 160–164.

- ↑ Brooks 2005, p. 217.

- ↑ Beevor 2014, p. 682.

- ↑ Toland 2003, p. 516.

- ↑ Battle of Saipan – The Final Curtain, David Moore

- ↑ Toland 2003, p. 519.

- ↑ Smith & Finch 1949, p. 181.

- ↑ Philip A. Crowl, "Campaign in the Marianas", vol. 9., United States Army in World War II, The War in the Pacific

- ↑ Bix 2000, p. 478.

- ↑ Frank 1999, p. 90–91.

- ↑ Kawamura 2015, pp. 114.

- ↑ Kawamura 2015, pp. 129–130.

- ↑ Shaw, Nalty & Turnbladh 1966, p. 346: see quote in United States Strategic Bombing Survey 1946, p. 297

- ↑ Hallas 2019, p. 440; Hoffman 1950, p. 260: see quote in United States Strategic Bombing Survey 1946, p. 355

- ↑ Hoyt 2001, pp. 348–349.

- ↑ Hoyt 2001, pp. 352.

- 1 2 Hallas 2019, p. 458.

- 1 2 Gilhooly 2011.

- ↑ Hallas 2019, p. 463.

- ↑ Astroth 2019, p. 165.

- ↑ Trefalt 2018, pp. 255–256.

- ↑ Hughes 2010.

- ↑ Astroth 2019, p. 105.

- ↑ Astroth 2019, p. 167.

- ↑ Astroth 2019, p. 25.

- ↑ "NHL nomination for Landing Beaches; Aslito/Isley Field; & Marpi Point, Saipan Island". National Park Service. Retrieved 14 April 2015.

- ↑ "American Memorial Park". National Park Foundation. Archived from the original on 1 October 2022.

- ↑ "サイパン慰霊祭 (Saipan Memorial Service)". 公益財団法人太平洋戦争戦没者慰霊協会 (Pacific War Memorial Association, inc.). Archived from the original on 30 December 2016.

References

Books

- Astroth, Alexander (2019). Mass Suicides on Saipan and Tinian, 1944: An Examination of the Civilian Deaths in Historical Context. McFarland. ISBN 9781476674568. OCLC 1049791315.

- Beevor, Antony (2014) [2012]. The Second World War. Phoenix. ISBN 9781780225647. OCLC 1311140909.

- Bix, Herbert P. (2000). Hirohito and the Making of Modern Japan. Harper Collins. ISBN 9780060193140. OCLC 43031388.

- Brooks, Victor (2005). Hell Is Upon Us: D-Day in the Pacific, June–August 1944. Da Capo Press. ISBN 9780306813696. OCLC 61211333.

- Crowl, Philip A. (1993) [1960]. Campaign in the Marianas. Vol. 9. Center of Military History, United States Army. OCLC 1049152860.

- Frank, Richard B. (1999). Downfall: The End of the Imperial Japanese Empire. Random House. ISBN 9780679414247. OCLC 40783799.

- Goldberg, Harold J. (2007). D-Day in the Pacific: The Battle of Saipan. Indiana University Press, 2007. ISBN 978-0-253-34869-2. OCLC 73742593.

- Hallas, James H. (2019). Saipan: The Battle That Doomed Japan in World War II. Stackpole. ISBN 9780811768436. OCLC 1052877312.

- Hoffman, Carl W. (1950). Saipan: The Beginning of the End. Historical Branch, United States Marine Corps. OCLC 564000243.

- Hoyt, Edwin P. (2001) [1986]. Japan's War: The Great Pacific Conflict. ISBN 9780815411185. OCLC 45835486.

- Kawamura, Noriko (2015). Emperor Hirohito and the Pacific War. University of Washington Press. ISBN 9780295806310. OCLC 922925863.

- Lacey, Sharon T. (2013). Pacific Blitzkrieg: World War II in the Central Pacific. University of North Texas Press. ISBN 9781574415254. OCLC 861200312.

- McManus, John C. (2021). Island Infernos. Penguin. ISBN 9780451475060. OCLC 1260166257.

- Morison, Samuel Eliot (1981) [1953]. New Guinea and the Marianas, March 1944–August 1944. History of United States Naval Operations in World War II. Vol. 8. Little Brown. ISBN 9780316583084. OCLC 10926173.

- Shaw, Henry I., Jr.; Nalty, Bernard C.; Turnbladh, Edwin T. (1966). Central Pacific Drive". History of U.S. Marine Corps Operations in World War II. Vol. 3. Historical Branch, G–3 Division, Headquarters, U. S. Marine Corps. ISBN 9780898391947. OCLC 927428034.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Toland, John (2003) [1970]. The Rising Sun: The Decline and Fall of the Japanese Empire 1936–1945. Random House. ISBN 9780812968583. OCLC 52441692.

- Toll, Ian W. (2015). The Conquering Tide: War in the Pacific Islands, 1942–1944. W. W. Norton. ISBN 978-0393080643. OCLC 902661305.

Journal articles and reports

- Cloud, Preston; Schmidt, Robert G.; Burke, Harold W. (1956). Geology of Saipan: Mariana Islands- Part 1. General Geology (PDF) (Report). United States Geological Survey. Archived from the original (PDF) on 28 February 2017.

- The Commonwealth of the Northern Mariana Islands: Final Post Disaster Watershed Plan (Report). US Army Corps of Engineers. 2022. Archived from the original (PDF) on 17 January 2024.

- Hughes, Matthew (2010). "When soldiers kill civilians: The battle for Saipan, 1944". History Today. 60 (2): 42–48. Archived from the original on 27 January 2010.

- Trefalt, Beatrice (2018). "The Battle of Saipan in Japanese civilian memoirs: non-combatants, soldiers and the complexities of surrender". Journal of Pacific History. 53: 3. doi:10.1080/00223344.2018.1491300 – via academia.edu.

Online resources

- "American Memorial Park: Battle of Saipan". National Park Service. Archived from the original on 17 May 2022.

- Gilhooly, Rob (15 May 2011). "Japan's Renegade Hero Gives Saipan New Hope". Japan Times. Archived from the original on 6 July 2015.

Primary Sources

- Sheeks, Robert B. (1945). "Civilians in Saipan". Far Eastern Survey. 14 (2): 109–113. JSTOR 3022063.

- Smith, Holland M.; Finch, Percy (1949). Coral and Brass. Charles Scribner's Sons. OCLC 367235.

- United States Strategic Bombing Survey (1946). Interrogations of Japanese Officials. Vol. 2. U. S. Government Printing Office. ISBN 9780598449320. OCLC 3214951. Archived from the original on 17 November 2015.

Further reading

Books

- Bright, Richard Carl (2007). Pain and Purpose in the Pacific: True Reports Of War. Trafford Publishing. ISBN 978-1-4251-2544-8.

- Denfeld, D. Colt (1997). Hold the Marianas: The Japanese Defense of the Mariana Islands. White Mane Pub. ISBN 1-57249-014-4.

- Gailey, Harry A. (1986). Howlin' Mad Vs. the Army: Conflict in Command, Saipan 1944. Presidio Press. ISBN 0-89141-242-5.

- Hornfischer, James D. (2016). The Fleet at Flood Tide: The U.S. at Total War in the Pacific, 1944–1945. Random House Publishing Group. ISBN 978-0345548726.

- Jones, Don (1986). Oba, The Last Samurai. Presidio Press. ISBN 0-89141-245-X. OCLC 13847435.

- Love, Edmund G. (1982). The 27th Infantry Division in World War II. Battery Press. ISBN 978-0898390568.

- Manchester, William (1980). Goodbye, Darkness A Memoir of the Pacific War. Boston – Toronto: Little, Brown and Co. ISBN 0-316-54501-5.

- O'Brien, Francis A. (2003). Battling for Saipan. Presidio Press. ISBN 0-89141-804-0.

- Petty, Bruce M. (2001). Saipan: Oral Histories of the Pacific War. McFarland and Company. ISBN 0-7864-0991-6.

- Rottman, Gordon; Howard Gerrard (2004). Saipan & Tinian 1944: Piercing the Japanese Empire. Osprey Publishing. ISBN 1-84176-804-9.

- Sauer, Howard (1999). "Torpedoed at Saipan". The Last Big-Gun Naval Battle: The Battle of Surigao Strait. Palo Alto, California: The Glencannon Press. ISBN 1-889901-08-3. – Firsthand account of naval gunfire support by a crewmember of USS Maryland.

- Tachovsky, Joseph (2020). 40 Thieves on Saipan: The Elite Marine Scout-Snipers in One of WWII's Bloodiest Battles. Regnery History. ISBN 978-1684510481.

- Slaon, Bill (2017). Their Backs against the Sea: The Battle of Saipan and the Largest Banzai Attack of World War II. Da Capo Press. ISBN 978-0306824715.

Web

- Chapin, Captain John C. (1994). The Battle for Saipan. Washington D.C.: United States Marine Corps Historical Division. PCN 19000312300. Archived from the original on 11 December 2008. Retrieved 12 December 2008.

- Chen, C. Peter. "The Marianas and the Great Turkey Shoot". World War II Database. Retrieved 31 May 2005.

- Saipan – a 2nd Marine Division pamphlet describing certain expected features of the invasion and combat, including the presence of a large civilian population.

- Breaching the Marianas: The Battle for Saipan (Marines in World War II Commemorative Series)

- https://web.archive.org/web/20070516034652/http://www.geocities.jp/torikai007/war/1944/saipan.html Banzai charge in Saipan: Gyokusai] (in Japanese) Suicide for the Emperor?

- Anderson, Charles R. (2003). Western Pacific. U.S. Army Campaigns of World War II. United States Army Center of Military History. CMH Pub 72-29. Archived from the original on 3 February 2012. Retrieved 3 November 2004.

- Dyer, George Carroll (1956). "The Amphibians Came to Conquer: The Story of Admiral Richmond Kelly Turner". United States Government Printing Office. Archived from the original on 21 May 2011. Retrieved 5 May 2011.

- SMU's Frank J. Davis World War II Photographs contain 129 images of Saipan, including 18 images depicting the surrender of the famous "hold-out" Japanese forces under the command of Captain Oba in December 1945

- "Operation Forager: The Battle of Saipan". Naval History and Heritage Command.