| Battle of Shaiba | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the Mesopotamian Campaign of World War I | |||||||||

Machine gunners of the 120th Rajputana Rifles at the Battle of Shaiba, 12 April 1915 | |||||||||

| |||||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||||

|

| |||||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||||

| Major General Charles Melliss | Lieutenant Colonel Süleyman Askerî | ||||||||

| Strength | |||||||||

| 6,156 | 18,000 | ||||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||||

| 1,570 | 2,435 | ||||||||

| Approximate figures | |||||||||

Location within Iraq | |||||||||

The Battle of Shaiba (12–14 April 1915) was a battle of World War I fought between British and Ottoman forces, the latter trying to retake the city of Basra from the British.

Background

By capturing Basra, the British had taken an important communications and industrial centre. The British had consolidated their hold on the city and brought in reinforcements. The Ottomans gathered their forces and launched a counteroffensive to retake the city and push the British out of Mesopotamia.

The battle

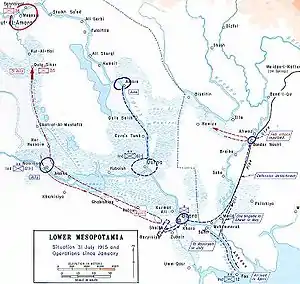

The Ottoman commander Süleyman Askeri had about 4,000 regular soldiers, including the Istanbul Fire Brigade Regiment and a large number of irregular Arabs and Kurds, numbering maybe 14,000, for a total of 18,000 personnel.[1] He chose to attack the British positions around Shaiba, southwest of Basra. Travel between =asra and Shaiba was difficult because seasonal floods had turned the area into a lake, and movement went via boat. The British garrison at Shaiba consisted of about 7,000 men in a fortified camp including a trench and barbed wire. At 5 AM on the 12th, the Ottoman troops started with a bombardment. That evening starting at dusk they tried to crawl through gaps in the British barbed wire, but were repulsed.[2] By morning of the 13th the Ottoman troops had withdrawn to their positions at Barjisiyeh Wood. Later the next day it was apparent that some Ottomans and Arab irregulars were trying to slip around Shaiba, and maybe get to Basra by bypassing the town. The British, under General Charles Melliss, sent the 7th Hariana Lancers and later the 104th Wellesley's Rifles to attack the Arabs, but those attacks were failures.[3] Melliss then attacked with the 2nd Dorsets and the 24th Punjabis, backed by artillery fire, and they routed the Arab irregulars, capturing 400 and dispersing the rest. The Arab irregular forces would not take part in the rest of the battle. Sulaiman Askari had his Ottoman regular troops fall back on Barjisiyeh Wood. On 14 April the British left Shaiba to look for the remaining Ottoman forces. They found them at Barjisiyeh Wood. Fighting started at about 10:30 AM and lasted until 5 PM. Melliss had to adjust his forces on the battlefield under fire to bring them to bear on the Ottoman positions. Ottoman fire was intense and by 4 PM the British attack had bogged down.[4] Men were thirsty and running low on ammunition, and the Ottoman regular troops showed no indication they were going to give up. The Dorsets then launched a bayonet charge on the Ottoman lines that caused the rest of the Indian troops to follow, and the Ottomans were overwhelmed.[5] They retreated from the battlefield. The British, worn out from the day's fighting with little transportation and with their cavalry tied down elsewhere, did not pursue. Sulaiman Askari would end up committing suicide over the loss, which he blamed on the Arab irregulars and their failure to support him.[6] On the British side the battle was described as a "soldier's battle" meaning a hard fought infantry fight, where they, especially the British troops, decided the day.[7]

Aftermath

The battle was important as it was the last time the Ottomans would threaten Basra. After the battle it would be the British who generally held the initiative in Mesopotamia. It also changed Arab attitudes. They began to distance themselves from the Ottomans, and later revolts broke out in Najaf and Karbala up river.[8]

Major George Wheeler of the 7th Hariana Lancers was awarded a posthumous Victoria Cross for his actions during the battle.

See also

References

- ↑ Charles Townsend, Desert Hell, The British Invasion of Mesopotamia (Harvard University Press, Cambridge, Massachusetts, 2010), 84.

- ↑ A.J. Barker, The First Iraq War, 1914-1918, Britain's Mesopotamian Campaign,(Enigma, New York, 2009; originally published in 1967 as The Bastard War(US)/The Neglected War(UK)), 50.

- ↑ A.J. Barker, The First Iraq War, 1914-1918, Britain's Mesopotamian Campaign,(Enigma, New York, 2009; originally published in 1967 as The Bastard War(US)/The Neglected War(UK)), 51.

- ↑ A.J. Barker, The First Iraq War, 1914-1918, Britain's Mesopotamian Campaign,(Enigma, New York, 2009; originally published in 1967 as The Bastard War(US)/The Neglected War(UK)), 53.

- ↑ A.J. Barker, The First Iraq War, 1914-1918, Britain's Mesopotamian Campaign,(Enigma, New York, 2009; originally published in 1967 as The Bastard War(US)/The Neglected War(UK)), 53.

- ↑ Charles Townsend, Desert Hell, The British Invasion of Mesopotamia (Harvard University Press, Cambridge, Massachusetts, 2010), 90.

- ↑ A.J. Barker, The First Iraq War, 1914-1918, Britain's Mesopotamian Campaign,(Enigma, New York, 2009; originally published in 1967 as The Bastard War(US)/The Neglected War(UK)), 54-55.

- ↑ Charles Townsend, Desert Hell, The British Invasion of Mesopotamia (Harvard University Press, Cambridge, Massachusetts, 2010), 90-91.