| Battle of Trois-Rivières | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the American Revolutionary War | |||||||

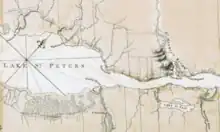

Detail of a 1759 map showing Trois-Rivières and Sorel. | |||||||

| |||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

|

|

| ||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

|

|

| ||||||

| Strength | |||||||

| 2,000[1] | 1,000+[2] | ||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||

|

30–50 killed[3][4] c. 30 wounded[3] 236 captured[5] |

8 dead, | ||||||

| Official name | Battle of Trois-Rivières National Historic Site of Canada | ||||||

| Designated | 1920 | ||||||

The Battle of Trois-Rivières was fought on June 8, 1776, during the American Revolutionary War. A British army under Quebec Governor Guy Carleton defeated an attempt by units from the Continental Army under the command of Brigadier General William Thompson to stop a British advance up the Saint Lawrence River valley. The battle occurred as a part of the American colonists' invasion of Quebec, which had begun in September 1775 with the goal of removing the province from British rule.

The crossing of the Saint Lawrence by the American troops was observed by Quebec militia, who alerted British troops at Trois-Rivières.[6] A local farmer led the Americans into a swamp, enabling the British to land additional forces in the village, and to establish positions behind the American army. After a brief exchange between an established British line and American troops emerging from the swamp, the Americans broke into a somewhat disorganized retreat. As some avenues of retreat were cut off, the British took a sizable number of prisoners, including General Thompson and much of his staff.

This was the last battle of the war fought on Quebec soil. Following the defeat, the remainder of the American forces, under the command of John Sullivan, retreated, first to Fort Saint-Jean, and then to Fort Ticonderoga.

Background

The Continental Army, which had invaded Quebec in September 1775, suffered a severe blow in the disastrous attack on Quebec City on New Year's Eve in 1775. Following that loss, Benedict Arnold and the remnants of the army besieged Quebec until May 1776.[7]

Early on May 6, three Royal Navy ships sailed into Quebec Harbour. Troops on these ships were immediately sent into the city and, not long after, General Guy Carleton formed them up and marched them out to the American siege camp.[8] General John Thomas, then in command of the American forces, had already been making arrangements to retreat, but the British arrival threw his troops into a panic. He led a disorganized retreat that eventually reached Sorel on about May 18.[9]

British forces at Trois-Rivières

Throughout the month of May and into early June, ships carrying troops and war supplies continued to arrive at Quebec. By June 2, Carleton had added the 9th, 20th, 29th, 53rd and 60th regiments of foot, along with General John Burgoyne, to his command. Also arriving in the fleet were Hessian troops from Brunswick commanded by Baron Riedesel.[10]

After the Americans' flight early in May, Carleton took no significant offensive steps but on May 22, he sent ships carrying elements of the 47th and 29th Foot to Trois-Rivières under Allan Maclean's command.[11] Brigadier General Simon Fraser led more forces to Trois-Rivières on June 2. By June 7, the forces on the ground at Trois-Rivières had grown to nearly 1,000, and 25 ships carrying additional troops and supplies were anchored in the river near the village and for several miles upriver.[12][13]

American arrangements

Since Thomas's retreat was instigated by the early arrival of three ships of the fleet carrying only a few hundred troops, he was unaware of the true size of the British army. In a war council at Sorel on May 21, which included representatives of the Second Continental Congress, a decision was reached to make a stand at Deschambault, between Trois-Rivières and Quebec. This decision was reached based on sketchy reports and rumors of the British troop strengths and was dominated by the non-military Congressional representatives. Thomas contracted smallpox on May 21, from which he died on June 2.[14] He was briefly replaced by Brigadier General William Thompson, who relinquished command to General John Sullivan when he arrived on June 5 at Sorel with further reinforcements from Fort Ticonderoga.[15]

On June 5, just hours before Sullivan's arrival, Thompson sent 600 troops under the command of Colonel Arthur St. Clair toward Trois-Rivières with the goal of surprising and beating back the small British force believed to be there. Sullivan, on his arrival at Sorel, immediately dispatched Thompson with an additional 1,600 men to follow. These forces caught up with St. Clair at Nicolet, where defenses against troop movements on the river were erected the next day. On the night of June 7, Thompson, St. Clair, and about 2,000 men crossed the river, landing at Pointe du Lac, a few miles above Trois-Rivières.[16]

Battle

The American crossing had been seen by a local militia captain, who rushed to the British camp at Trois-Rivières and reported to General Fraser.[17] Thompson left 250 men to guard the landing and headed the rest towards Trois-Rivières. Unfamiliar with the local terrain, he convinced Antoine Gautier, a local farmer, to guide the men to Trois-Rivières. Gautier proceeded, apparently intentionally, to lead the American army into a swampy morass from which it took them hours to extricate themselves.[18] In the meantime, the British, having been alerted to the American presence, proceeded to land troops from the fleet and formed battle lines on the road outside the village.[19] Ships were also sent up to Pointe du Lac, where they drove the American guards there to flee across the river with most of the boats.[20]

Some of the Americans, led by Thompson, made their way out of the swamp to be confronted by HMS Martin, which drove them back into the swamp with grapeshot.[1] A column of men under Colonel Anthony Wayne fared only a little better, arriving out of the swamp only to face Fraser's formation. A brief exchange of fire took place: but the Americans, clearly outmatched by Fraser's forces, broke and ran, leaving arms and supplies behind. Portions of the American force retreated to the edge of the woods, which gave them some cover, and attempted to engage some of the British troops: but fire from those troops kept them off the road and fire from some of the ships in the river kept them from the shore.[17] St. Clair and a number of men made it back to the landing site, only to find it occupied by the British troops. Only by returning to the swampy woods and continuing to flee upriver did these men escape capture at that time.[20] Wayne eventually managed to form a rear guard of about 800 men, which attempted an attack on the British position; but they were driven back into the woods. Wayne then led a staggered retreat, in which companies of men slipped away, with the woods giving cover to hide their true numbers.[21]

General Carleton arrived in Trois-Rivières late in the action.[22] A detachment of British forces led by Major Grant had taken control of a bridge over the Rivière-du-Loup, a critical crossing for the Americans retreating along the north shore of the Saint Lawrence.[23] Carleton ordered Grant to withdraw, allowing most of the Americans to escape, either because he did not want to deal with large numbers of prisoners or because he wanted to demoralize the Americans further.[3][22] A significant number of Americans did not make it that far, and were captured. These included General Thompson and seventeen of his officers. It was not until June 13 that the British finished rounding up the stragglers. In all, 236 captives were taken.[5][24] Brendan Morrissey says that about 30[3] Americans were killed in the battle, while Howard Peckham gives a figure of 50 Americans killed.[4]

Aftermath

Scattered fragments of the American army made their way overland on the northern shore to Berthier, where they crossed over to Sorel. Some did not return until June 11. Sullivan, who counted 2,500 effective troops under his command, at first wanted to make a stand at Sorel, but smallpox, desertions, and word that the British fleet was again under sail to come upriver convinced him it was time to retreat.[25] By June 17, the Continental Army had left the province; but not before it had attempted to burn Montreal, as well as destroying Fort Saint-Jean and any boats of military value capable of navigating Lake Champlain.[26]

Carleton ordered most of the British army to sail upriver toward Sorel on June 9, but they did not actually leave until he joined them on June 13.[27] A detachment of 1200 men under Fraser marched up the northern shore toward Berthier and Montreal. The British fleet arrived at Sorel late on the 14th; the Americans had left there just that morning.[27] Elements of the British army entered Montreal on June 17, and also arrived at Fort Saint-Jean in time to see the last Americans (the very last one reported to be Benedict Arnold) push away from its burning remnants.[26]

The captives were treated quite generously by Carleton. Although the conditions of their imprisonment were not always good, he provided them with clothing, and eventually had all but the officers transported to New York and released.[17]

Legacy

A site near the Le Jeune bridge was designated a National Historic Site of Canada in 1920 in order to commemorate the battle.[28]

There are three plaques in the city of Trois-Rivières commemorating aspects of the battle. A plaque honouring the British participants was placed at the National Historic Site by the Historic Sites and Monuments Board of Canada. A plaque honouring the American dead was placed in the Parc Champlain by the Daughters of the American Revolution in August 1985.[29] The third plaque honours Antoine Gauthier for his role in misleading the American troops.

During the American retreat from Quebec, and in this battle, wounded soldiers were treated at the Ursuline convent in Trois-Rivières. Congress never authorized payment for these services and the convent has retained the bill. By the early 21st century, the original bill of about £26 was estimated to be equivalent to between ten and twenty million Canadian dollars, if compound interest was applied.[29][30] On July 4, 2009, during festivities marking the town's 375th anniversary, American Consul-General David Fetter symbolically repaid the debt to the Ursulines with a payment of C$130.[31]

Footnotes

- 1 2 Morrissey, p. 69

- ↑ It is impossible to accurately gauge how many British troops actually participated in the action. There were more than 1,000 on the ground when they were alerted to the American presence; it is unknown how many were disembarked from the ships in assistance. For example, Smith, p. 413 mentions that General Nesbitt landed "a strong force" at Pointe-du-Lac; none of the other major sources give any count, or clear indication of how many forces were landed to assist Fraser at Trois-Rivières.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Morrissey, p. 70

- 1 2 Peckham, p. 18

- 1 2 Smith, p. 416

- ↑ "Battle of Three Rivers (Trois-Rivières)". American Revolutionary War. November 19, 2017. Retrieved June 8, 2019.

- ↑ Stanley, pp. 37–104

- ↑ Stanley, p. 108

- ↑ Stanley, p. 126

- ↑ Smith, pp. 408–410

- ↑ Stanley, p. 125

- ↑ Fryer, p. 139

- ↑ Smith, p. 411

- ↑ Stanley, pp. 126–127

- ↑ St. Clair Papers, p. 17

- ↑ St. Clair Papers, p. 18

- 1 2 3 Stanley, p. 128

- ↑ Stanley, p. 127

- ↑ Lanctot, p. 144

- 1 2 Hartley, p. 99

- ↑ Morrissey, pp. 69–70

- 1 2 Smith, p. 414

- ↑ Smith, p. 413

- ↑ Boatner, p.1117

- ↑ Stanley, pp. 129–130

- 1 2 Stanley, pp. 130–132

- 1 2 Fryer, p. 142

- ↑ "Battle of Trois-Rivières". Directory of Designations of National Historic Significance of Canada. Parks Canada. Retrieved March 5, 2012.

- 1 2 Cécil, p. 27

- ↑ Roy-sole

- ↑ Bourgoing-Alarie (2009)

References

- Boatner, Mark Mayo (1973) [1966]. Cassell's Biographical Dictionary of the American War of Independence, 1763–1783. London: Cassell & Company. ISBN 0-304-29296-6.

- Bourgoing-Alarie, Marie-Ève (July 4, 2009). "Mieux vaut tard que jamais!" (in French). L'Hebdo Journal. Archived from the original on July 7, 2009. Retrieved July 13, 2009.

- Cécil, Pierre (March–April 2000). "La Bataille de Trois-Rivières". Traces (in French). Société D'Histoire – Appartenance Mauricie. 30 (2).

- Fryer, Mary Beacock (1996) [1987]. Allan Maclean, Jacobite General: The Life of an Eighteenth Century Career Soldier. Toronto: Dundurn Press. ISBN 978-1-55002-011-3.

- Lanctot, Gustave (1967). Canada and the American Revolution 1774–1783. Cambridge, Massachusetts: Harvard University Press. OCLC 814409890.

- Morrissey, Brendan (2003). Quebec 1775: The American Invasion of Canada. Hook, Adam (trans.). Oxford, UK: Osprey Publishing. ISBN 978-1-84176-681-2.

- Peckham, Howard H. (1974). The Toll of Independence: Engagements & Battle Casualties of the American Revolution. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. ISBN 0-226-65318-8.

- Roy-Sole, Monique (April 2009). "Trois-Rivières – A tale of tenacity". Canadian Geographic. Archived from the original on May 23, 2009. Retrieved March 25, 2009.

- Smith, Justin H (1907). Our Struggle for the Fourteenth Colony, vol 2. New York: G.P. Putnam's Sons. ISBN 9780306706332. OCLC 259236.

- Smith, William Henry, ed. (1882). The St. Clair Papers. Vol. 1. Cincinnati, Ohio: Robert Clarke & Company. OCLC 817707.

- Stanley, George (1973). Canada Invaded 1775–1776. Toronto: Hakkert. ISBN 978-0-88866-578-2.

- Hartley, Thomas (1908). Proceedings and Addresses, Volume 17. Lancaster, Pennsylvania: Pennsylvania–German Society. OCLC 1715275.