| Battle of Vaslui | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the Moldavian-Ottoman Wars Ottoman-Hungarian Wars and the Polish-Ottoman Wars | |||||||

Location of the battle | |||||||

| |||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

|

Moldavia Kingdom of Poland Kingdom of Hungary | Ottoman Empire | ||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

|

Stephen III of Moldavia Mihály Fants[3] | Hadım Suleiman Pasha | ||||||

| Strength | |||||||

|

30,000–40,000 Moldavians 5,000 Székelys 2,000 Polish 1,800 Hungarians 20 cannons | 60,000–120,000 Ottomans | ||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||

| ~5,000 killed and wounded |

~40,000 killed[4] 4,000 captured[4] | ||||||

The Battle of Vaslui (also referred to as the Battle of Podul Înalt or the Battle of Racova) was fought on 10 January 1475, between Stephen III of Moldavia and the Ottoman governor of Rumelia, Hadım Suleiman Pasha. The battle took place at Podul Înalt ("the High Bridge"), near the town of Vaslui, in Moldavia (now part of eastern Romania). The Ottoman troops numbered up to 120,000, facing about 40,000 Moldavian troops, plus smaller numbers of allied and mercenary troops.[5]

Stephen inflicted a decisive defeat on the Ottomans, with casualties according to Venetian and Polish records reaching beyond 40,000 on the Ottoman side. Mara Branković (Mara Hatun), the former younger wife of Murad II, told a Venetian envoy that the invasion had been the worst ever defeat for the Ottomans.[6] Stephen was later awarded the title Athleta Christi ("Champion of Christ") by Pope Sixtus IV, who referred to him as "verus christianae fidei athleta" ("the true defender of the Christian faith").[7]

According to the Polish chronicler Jan Długosz, Stephen did not celebrate his victory; instead, he fasted for forty days on bread and water and forbade anyone to attribute the victory to him, insisting that credit be given only to the Lord.

Background

The conflict between Stephen and Ottoman Sultan Mehmed II worsened when both laid their claims to the historical region of Southern Bessarabia, now known under the name of Budjak. The region had belonged to Wallachia, but later succumbed to Moldavian influence under Petru Mușat and was possibly annexed to Moldavia in the late 14th century by Roman I of Moldavia.[8] Under Alexandru cel Bun, it had become an integral part of Moldavia and was successfully defended in 1420 against the first Ottoman attempt to capture castle Chilia.[9] The ports of Chilia and Akkerman (Romanian: Cetatea Albă) were essential for Moldavian commerce. The old trade route from Caffa, Akkerman, and Chilia passed through Suceava in Moldavia and Lwow in Poland (now in Ukraine).

Both Poland and Hungary had previously made attempts to control the region, but had failed; and for the Ottomans, "the control of these two ports and of Caffa was as much an economic as a political necessity",[10] as it would also enhance their control of Moldavia and serve as a valuable strategic point from which naval attacks could be launched against the Commonwealth of Poland-Lithuania. This is confirmed by a German chronicle which explains that Mehmet wanted to turn Moldavia into "some kind of fortress", and from there, to launch attacks against Poland and Hungary.[11] The Ottomans also feared the strategic position of Moldavia, whence it would only take 15 to 20 days to reach Constantinople.[12]

In 1448, Petru II of Moldavia awarded Chilia to John Hunyadi, the governor of Transylvania,[6] effectively ceding control of the strategic area on the Danube, with access to the Black Sea, to Hungary. With the assassination of Bogdan II of Moldavia in 1451 by his brother Petru Aron, the country fell into civil war as two pretenders fought for the throne: Aron and Alexăndrel.[13] Bogdan's son, Stephen, fled Moldavia together with his cousin, Vlad Dracula—who had sought protection at the Moldavian court – to Transylvania, at the court of Hunyadi.[14] Even though Hungary had made peace with the Turks in 1451, Hunyadi wanted to transform Wallachia and Moldavia into a barrier that would protect the kingdom from Ottoman expansion.[15] In the fall of 1453, after the Ottoman capture of Constantinople, Moldavia received an ultimatum to start paying tribute to the Porte;[16] two years later, on 5 October 1455, Aron sent the first Moldavian tribute to the Porte: a payment of 2,000 ducats.[17] With both Wallachia and Moldavia conducting a pro-Ottoman policy, the plan to install Vlad Țepeș as prince of Wallachia began to take shape. Sometime between April and July 1456, with the support of a few Hungarian troops and Wallachian boyars, Prince Vladislav II was dethroned and slain, as Vlad Țepeș took possession of the Wallachian throne;[15] and as such, Chilia became a shared Wallachian-Hungarian possession. In April 1457, Vlad Țepeș supported Stephen with 6,000 horsemen, which the latter used to invade Moldavia and occupy the Moldavian throne,[18] ending the civil war as Aron fled to Poland. The new prince continued sending the tribute that his uncle and Mehmed had agreed upon, and in such way, avoided any premature confrontation with his enemy. His first priority was to strengthen the country and to retrieve its lost territory. Because Aron resided in Poland, Stephen made a few incursions in southern Poland. The hostilities ended on 4 April 1459, when in a new treaty between the two countries, Moldavia accepted vassalage and Poland returned Hotin back to Moldavia; the latter also assumed the obligation to support Moldavia in retrieving Chilia and Cetatea Albă.[19] It was also in the interest of Poland to have the area belonging to Moldavia, as it would increase their commerce in the region.[20] On 2 March 1462, in a renewed treaty between the two countries, it was agreed that no Moldavian territory should remain under foreign rulership, and if such territory was under foreign rulership, that territory should be regained.[20] Later that year, it is believed that Stephen asked Vlad to return Chilia back to Moldavia – a demand which was most likely refused.[21]

On 22 June, when Vlad was fighting Mehmed, Stephen allied himself with the Sultan and with some Turkish assistance, he launched an attack on Chilia.[22] The fortress, defended by tall stone walls and 12 cannons, was among the strongest fortifications along the Danube at that time.[23] The Wallachians rushed to the scene with 7,000 men, and together with the Hungarian garrison battled the Moldavians and the Turks for eight days. They managed to defend the town, while wounding Stephen in his foot with shrapnel.[22] In 1465, while Vlad was imprisoned in Hungary, Stephen again advanced towards Chilia with a large force and siege weapons; but instead of besieging the fortress, he showed the garrison – who favoured the Polish King – a letter in which the King required them to surrender the fortress. This they did, and Stephen entered the fortress where he found "its two captains, rather tipsy, for they have been to a wedding".[24] Mehmed was furious about the news and claimed Chilia for being a part of Wallachia – which now was a vassal to the Porte – and demanded Stephen to give it over to him. The latter refused, however, and recruited an army, forcing Mehmed – who was not yet ready to wage war – to accept the situation, if only for the time being.[24] The Moldavian prince, realising that a future war with Mehmed could not be avoided, tried to gain time by increasing his tribute to the Porte by 50 percent (to 3,000 ducats); and also sent an envoy to Constantinople with gifts for the sultan.[25] In 1467, Matthias Corvinus of Hungary launched an expedition against Moldavia in order to punish Stephen for annexing the region. The invasion ended in a disaster for the Hungarians as they suffered a bitter defeat at the Battle of Baia, where Corvinus was thrice wounded by arrows and had to be "carried from the battlefield on a stretcher, to avoid him falling into the hands of the enemy".[26]

To secure his southern frontier from Ottoman threats, Stephen wanted to liberate Wallachia – where the hostile Radu the Handsome, the halfbrother of Vlad Țepeș ruled – from Ottoman dominion. In 1470, he invaded the country and burned down the town of Brăila[27] and in 1471, Stephen and Radu confronted each other in Moldavia, where the latter was defeated.[28] Meanwhile, Genoa, which possessed several colonies in the Crimea, began to worry about Stephen's growing influence in the region; and ordered her colonies to do whatever was needed to revenge past mischief from which allegedly, the Genovese had suffered.[28] The colonies in turn persuaded the Tatars to attack Moldavia. Later that year, the Tatars invaded the country from the north, causing great damage to the land and enslaving many.[28] Stephen replied by invading Tatar territory with Polish assistance. In 1472, Uzun Hassan of Ak Koyunlu invaded the Ottoman Empire from the east, causing a great crisis to the empire. He was defeated the following year, but this unexpected event, as it is explained in a contemporary source, encouraged Venice and Hungary to renew their war on the Ottomans, and Moldavia to free herself from any Ottoman influence.[28] In 1473, Stephen stopped paying the annual tribute to the Porte[29] and as a reaction to this, an Italian letter, dated from 1473 to Bartolomeo Scala, secretary of the Republic of Florence, reveals that Mehmed had left Constantinople on 13 April and was planning to invade Moldavia from land and sea.[30] Stephen still hoped to make peace with Radu and asked the Polish king to work as mediator.[28] The peace attempts failed and the conflict intensified with three leaders challenging each other for the Wallachian throne: Radu, who was supported by Mehmed; the seemingly loyal Basarab Laiotă, who at first was supported by Stephen; and Basarab Ţepeluş cel Tânăr—who would gain the support of Stephen after Laiotă's betrayal.[31] A series of "absurd"[31] clashes followed, starting with another confrontation between Stephen and Radu on 18–20 November, at Râmnicu Sărat, where the latter suffered his second defeat at the hands of the Moldavian "warlike" prince.[31] A few days later, on 28 November, the Ottomans intervened with an army consisting of 12,000 Ottomans and 6,000 Wallachians, but "they incurred heavy losses and fled across the Danube".[31] After capturing the castle of Bucharest, Stephen put Laiotă on the throne,[27] but on 31 December, a new Ottoman army of 17,000 set camp around river Bârlad, laying waste to the countryside, and intimidating the new prince into abandoning his Wallachian throne and fleeing to Moldavia.[31] In the spring of 1474, Laiotă took the Wallachian throne for the second time; and in June, he made the decision to betray his protégé by submitting to Mehmet.[31] Stephen then invested his support into a new candidate, named Ţepeluş (little spear), but his reign was even shorter, as it only lasted a few weeks after being defeated by Laiotă in battle on 5 October. Two weeks later, Stephen returned to Wallachia and forced Laiotă to flee.[31] Mehmed, tired of what transpired in Wallachia, gave Stephen an ultimatum to forfeit Chilia to the Porte, to abolish his aggressive policy in Wallachia, and to come to Constantinople with his delayed homage.[29] The Prince refused and in November 1474, he wrote to the Pope to warn him of further Ottoman expansion, and to ask him for support.[32]

Preparations for war

Ottomans

Mehmed ordered his general, Suleiman Pasha, to end the siege of Venetian-controlled Shkodër[33] (now in Albania), to assemble his troops in Sofia, and from there to advance with additional troops towards Moldavia. For these already exhausted Ottoman troops, who had besieged the city from 17 May to 15 August,[25] the transit from Shkodër to Moldavia was a month's journey through bad weather and difficult terrain.[34] According to Długosz, Suleiman was also ordered that after inflicting defeat on Stephen, he was to advance towards Poland, set camp for the winter, then invade Hungary in spring, and unite his forces with the army of the Sultan. The Ottoman army consisted of Janissaries and heavy infantry, which were supported by the heavy cavalry sipahis and by the light cavalry (akinci), who would scout ahead. There were also Tatar cavalry and other troops (such as the Timariots) from vassal states. Twenty thousand Bulgarian peasants were also included in the army; their main tasks were to clear the way for the rest of the army by building bridges over waters and removing snow from the roads, and to drive supply wagons.[35] In total, the Ottoman cavalry numbered 30,000.[36] In September 1474, the Ottoman army gathered in Sofia, and from there, Suleiman marched towards Moldavia by crossing the frozen Danube on foot.[37] His first stop was Wallachia, which he entered via Vidin and Nicopolis. His army rested in Wallachia for two weeks, and was later met by a Wallachian contingent of 17,000 under Basarab Laiotă, who had changed sides to join the Ottomans.

Moldavians

Stephen was hoping to gain support from the West, and more specifically from the Pope. However, the help that he received was modest in numbers. The Hungarian Kingdom sent 1,800 Hungarians, while Poland sent 2,000 horsemen.[38] Stephen recruited 5,000 Székely soldiers.[38] The Moldavian army consisted of twenty cannon; light cavalry (Călăraşi); elite, heavy cavalry – named Viteji, Curteni, and Boyars – and professional foot soldiers. The army reached a strength of up to 40,000, of whom 10,000 to 15,000 comprised the standing army. The remainder consisted of 30,000 peasants armed with maces,[39] bows, and other home-made weapons. They were recruited into Oastea Mare (the Great Army), into which all able-bodied free men over the age of 14 were conscripted.

Battle

The invading army entered Moldavia in December 1474. To fatigue the Ottomans, Stephen had instituted a policy of scorched earth[38] and poisoned waters.[37] Troops who specialised in setting ambushes harassed the advancing Ottomans. The population and livestock were evacuated to the north of the country into the mountains.[40]

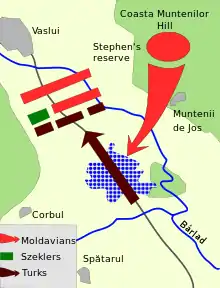

Ottoman scouts reported to Suleiman that there were untouched villages near Vaslui, and the Ottomans headed for that region. The winter made it difficult to set camp, which forced the Ottomans to move quickly and head for the Moldavian capital, Suceava. To reach Vaslui, where the Moldavian army had its main camp, they needed to cross Podul Înalt over the Bârlad River. The bridge was made of wood and not suitable for heavy transportation of troops.[37] Stephen chose that area for the battle – the same location where his father, Bogdan II, had defeated the Poles in 1450; and where he, at the age of 17,[41] had fought side by side with Vlad 'the Impaler'.[22] The area was ideal for the defenders: the valley was a semi-oval surrounded on all sides by hills covered by forest. Inside the valley, the terrain was marshy, which restricted troop movement.[41] Suleiman had full confidence in his troops and made few efforts to scout the area. On 10 January, on a dark and misty[40] Tuesday morning, the battle began. The weather was frigid, and a dense fog limited vision. The Ottoman troops were exhausted, and the torrent [?] made them look like "plucked chickens".[33] Stephen fortified the bridge, while setting and aiming his cannons at the structure. Peasants and archers were hidden in the forest, together with their Prince and his boyar cavalry.

The Moldavians made the first move by sending musicians to the middle of the valley. The sound of drums and bugles made Suleiman think that the entire Moldavian army awaited him there.[42] Instead, the centre of the valley held the Székely forces and the Moldavian professional army, which were ordered to make a slow retreat when they encountered the enemy. Suleiman ordered his troops to advance and, when they made enough progress, the Moldavian artillery started to fire, followed by archers and handgunners firing from three different directions.[33] The archers could not see the enemy for the fog, and, instead, had to follow the noise of their footsteps. The Moldavian light cavalry then helped to lure the Ottoman troops into the valley by making hit-and-run attacks. Ottoman cavalry tried to cross the wooden bridge, causing it to collapse.[43] Those Ottoman soldiers who survived the attacks from the artillery and the archers, and who did not get caught in the marshes, had to confront the Moldavian army, together with the Székely soldiers further up the valley. The 5,000 Székely soldiers were successful in repelling 7,000 Ottoman infantrymen. Thereafter, they made a slow retreat,[40] as instructed by Stephen, but were later routed by the Ottoman sipahi,[43] while the remaining Ottoman infantry attacked the Moldavian flanks.

Suleiman tried to reinforce his offensive, not knowing what had happened in the valley, but then Stephen, with the full support of his boyars, ordered a major attack. All his troops, together with peasants and heavy cavalry, attacked from all sides. Simultaneously, Moldavian buglers concealed behind Ottoman lines started to sound their bugles, and in great confusion some Ottoman units changed direction to face the sound.[44] When the Moldavian army attacked, Suleiman lost control of his army.[33] He desperately tried to regain control, but eventually was forced to signal a retreat. The battle lasted for four days,[45] with the last three days consisting of the fleeing Ottoman army being pursued by the Moldavian light cavalry and the 2,000-strong Polish cavalry until they reached the town of Obluciţa (now Isaccea, Romania), in Dobruja.

The Wallachians fled the field without joining battle and Laiotă now turned his sword against the Turks, who had hoped for a safe passage in Wallachia; on 20 January, he exited his castle and confronted some of the Turks that were lurking on his land. Thereafter, he took one of their flags and sent it to a Hungarian friend as proof of his bravery.[46] The Ottoman casualties were reported as 45,000, including four Pashas killed and a hundred standards taken.[47] Jan Długosz writes that "all but the most eminent of the Turkish prisoners are impaled",[48] and their corpses burned.[38] Only one was spared – the only son of the Ottoman general Isaac Bey, of the Gazi Evrenos family, whose father had fought with Mircea the Elder.[46] Another Polish chronicler reported that on the spot of the battle rested huge piles of bones upon each other, next to three immured crosses.[38]

Aftermath

After the battle, Stephen sent "four of the captured Turkish commanders, together with thirty-six of their standards and much splendid booty, to King Casimir in Poland", and implored him to provide troops and money to support the Moldavians in the struggle against the Ottomans. He also sent letters and a few prisoners and Turkish standards to the Pope and Hungarian King Matthias Corvinus, asking for support.[49] In response, "the arrogant Matthias writes to the Pope, the Emperor and other kings and princes, telling them that he has defeated a large Turkish army with his own forces under the Voivode of Wallachia".[50] The Pope's reply to Stephen denied him help, but awarded him with the "Athleta Christi",[51] while King Casimir pleaded "poverty both in money and men" and did nothing; his own men then accused him of sloth, and advised him to change his shameful behaviour or hand over his rule to someone else.[49] Chronicler Jan Długosz hailed Stephen for his victory in the battle:

Praiseworthy hero, in no respect inferior to other hero soldiers we admire. He was the first contemporary among the rulers of the world to score a decisive victory against the Turks. To my mind, he is the worthiest to lead a coalition of the Christian Europe against the Turks.[52]

Stephen tried to create a new coalition with the European powers, arguing that Mehmed's best troops were lost at Vaslui.[28] Upon hearing about the devastating defeat, Mehmed refused for several days to give audience to anyone; his other plans of expansion were put to rest as he planned revenge on Stephen.[6] In the following year, Mehmed invaded the country with an army of 150,000, which was joined by 10,000 Wallachians under Laiotă and 30,000 Tatars under Meñli I Giray. The Tatars, who called for a Holy War, attacked with their cavalry from the north and started to pillage the country. The Moldavians took chase after them, and routed and killed most of them. "The fleeing Tatars discard their weapons, their saddles and clothes, while some, as though crazed, jump into the River Dniepr".[53] Giray wrote to Mehmed that he could not wage more war against Stephen, as he had lost his son and two brothers, and had returned with only one horse.[54]

In July 1476, after killing 30,000 Ottomans, Stephen was defeated at the Battle of Valea Albă. However, the Ottomans were unsuccessful in their siege of the Suceava citadel and the Neamţ fortress, while Laiotă was forced to retreat back to Wallachia when Vlad and Stefan Báthory, Voivode of Transylvania, gave chase with an army of 30,000.[55] Stephen assembled his army and invaded Wallachia from the north, while Vlad and Báthory invaded from the west. Laiotă fled, and in November, Vlad Țepeș was installed on the Wallachian throne. He received 200 loyal knights from Stephen to serve as his loyal bodyguards, but his army remained small.

When Laiotă returned, Vlad Tepes went to battle and was killed by the Janissaries near Bucharest in December 1476. Laiotă again occupied the Wallachian throne, which urged Stephen to make another return to Wallachia and dethrone Laiotă for the fifth and last time, while a Dăneşti, Ţepeluş, was established as ruler of the country.

In 1484, the Ottomans under Bayezid II managed to conquer Chilia and Cetatea Albă and incorporate it into their empire under the name of Budjak, leaving Moldavia a landlocked principality for many years to come.

Between May and September 1488, Stephen built the Voroneţ Monastery to commemorate the victory at Vaslui; "the exterior walls – including a representation of the Last Judgment on the west wall – were painted in 1547 with a background of vivid cerulean blue. This is so vibrant that art historians refer to Voroneţ blue the same way they do Titian red."[56] In 1490, he extended his work by building another monastery of Saint John the Baptist. These monasteries served as cultural centres; today, they are on UNESCO's World Heritage List. Stephen's victory at Vaslui is considered one of the greatest Moldavian victories over the Ottomans, and as such "played a role in universal history" by securing the culture and civilization of the Christian West from the onslaught of Islam.[57]

References

- ↑ Kármán & Kunčevic 2013, p. 266.

- ↑ Ferencz Kállay (1850). Historiai brtekezés a' nemes székely nemzet' eredetéről: hadi és polgári intézeteiről a régi időkben

- ↑ Ferencz Kállay (1829). Historiai értekezés a' nemes székely nemzet' eredetéről: hadi és polgári intézeteiről a régi időkben [Historical discourse about the origin of the 'magnanimous szekler nation' : military and civil institutes in the past times.] (in Hungarian). Nagyenyed, Hungary: Fiedler Gottfried. p. 247. Retrieved 9 October 2010.

- 1 2 Liviu Pilat and Ovidiu Cristea, The Ottoman Threat and Crusading on the Eastern Border of Christendom during Vaslui, (Brill, 2006), 149.

- ↑ Kronika Polska mentions 40,000 Moldavian troops; Gentis Silesiæ Annales mentions 30,000 Ottoman troops and "no more than" 40,000 Moldavian troops; the letter of Stephen addressed to the Christian countries, sent on 25 January 1475, mentions 30,000 Ottoman troops; see also The Annals of Jan Długosz, p. 588;

- 1 2 3 Istoria lui Ştefan cel Mare, p. 133

- ↑ Saint Stephen the Great in his contemporary Europe (Respublica Christiana), p. 141

- ↑ Moldavia in the 11th–14th Centuries, pp. 218–19

- ↑ The Annals of Jan Długosz, p. 449

- ↑ The Ottoman Empire: The Classical Age 1300–1600, p. 129

- ↑ Gentis Silesiæ Annales

- ↑ Letter to Leonardo Loredano, written on 7 December 1502

- ↑ Studii Noi Despre Probleme Vechi — Din Istoria Evului Mediu Românesc, p. 92

- ↑ Studii Noi Despre Probleme Vechi – Din Istoria Evului Mediu Românesc, p. 93

- 1 2 Studii Noi Despre Probleme Vechi – Din Istoria Evului Mediu Românesc, pp. 92–93

- ↑ Studii Noi Despre Probleme Vechi – Din Istoria Evului Mediu Românesc, p. 91

- ↑ The Ottoman Law of War and Peace—The Ottoman Empire and Tribute Payers, p. 164

- ↑ Studii Noi Despre Probleme Vechi – Din Istoria Evului Mediu Românesc, p. 94

- ↑ Studii Noi Despre Probleme Vechi – Din Istoria Evului Mediu Românesc, p. 96

- 1 2 Studii Noi Despre Probleme Vechi – Din Istoria Evului Mediu Românesc, p. 134

- ↑ Studii Noi Despre Probleme Vechi – Din Istoria Evului Mediu Românesc, pp. 95–96

- 1 2 3 Vlad Dracul: Prince of many faces – His life and his times, p. 149

- ↑ Studii Noi Despre Probleme Vechi – Din Istoria Evului Mediu Românesc, p. 97

- 1 2 The Annals of Jan Długosz, p. 552

- 1 2 Semnificaţia Haracului în relaţiile Moldo-Otomane din vremea lui Ştefan cel Mare – Câteva Consideraţii

- ↑ The Annals of Jan Długosz, p. 566

- 1 2 Costin, N. Letopiseţul Ţărîi Moldovei

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Relaţiile internaţionale ale Moldovei în vremea lui Ştefan cel Mare

- 1 2 The Ottoman Law of War and Peace—The Ottoman Empire and Tribute Payers, p. 165

- ↑ Noi Izvoare Italiene despre Vlad Ţepeş şi Ştefan cel Mare; Studies and Materials of Medium History XX/2002

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 Mehmed the Conqueror and his time, p. 339

- ↑ Letter of Stephen, Vaslui 29 November 1474

- 1 2 3 4 The Chronicles of the Ottoman Dynasty

- ↑ Great Events

- ↑ Istoria lui Ştefan cel Mare, p.127

- ↑ Historia Turchesca

- 1 2 3 Istoria lui Ştefan cel Mare, p. 128

- 1 2 3 4 5 Kronika Polska

- ↑ Istoria lui Ştefan cel Mare, pp. 127, 130

- 1 2 3 The Ottoman Empire 1326–1699, p. 42

- 1 2 Istoria lui Ştefan cel Mare, p. 129

- ↑ Grigore U. Letopiseţul Ţărîi Moldovei

- 1 2 Istoria lui Ştefan cel Mare, p. 130

- ↑ Roumania Past and Present, Chapter XI.

- ↑ Documentary: Amintirile unui Pelerin, Antena 1

- 1 2 Istoria lui Ştefan cel Mare, pp. 131–32

- ↑ A Documented Chronology of Roumanian History – from prehistoric times to the present day, Oxford 1941, p. 108

- ↑ The Annals of Jan Długosz, p. 588

- 1 2 The Annals of Jan Długosz, pp. 588–9

- ↑ The Annals of Jan Długosz, p. 589

- ↑ "Romania - The Ottoman Invasions". countrystudies.us. U.S. Library of Congress. Archived from the original on 5 August 2011. Retrieved 8 February 2023.

- ↑ Historiae Polonicae, libri XIII, vol. II, note 528, Leipzig 1712.

- ↑ The Annals of Jan Długosz, pp. 592, 594

- ↑ Letter of Giray to Mehmed, 10–19 October 1476

- ↑ Diary of Ladislav, servant of Vlad; 7 August 1476

- ↑ Artistic Route Through Romania

- ↑ Catholic Encyclopedia

Bibliography

- Kármán, Gábor; Kunčevic, Lovro, eds. (2013). The European Tributary States of the Ottoman Empire in the Sixteenth and Seventeenth Centuries. Leiden: Brill. ISBN 9789004246065.

- Antena 1, Amintirile unui Pelerin (documentary).

- Babinger, Franz. Mehmed the Conqueror and his time ISBN 0-691-01078-1.

- Cândea, Virgil. Saint Stephen the Great in his contemporary Europe (Respublica Christiana), Balkan Studies 2004.

- Catholic Encyclopedia, Rumania (source: New Advent).

- Denize, Eugen. Semnificaţia Haracului în relaţiile Moldo-Otomane din vremea lui Ştefan cel Mare – Câteva Consideraţii.

- Długosz, Jan. The Annals of Jan Długosz. ISBN 1-901019-00-4.

- Ghyka, Matila. A Documented Chronology of Roumanian History – from prehistoric times to the present day, Oxford 1941.

- Florescu, R. Radu; McNally, T. Raymond. Dracula: Prince of many faces – His life and his times. ISBN 978-0-316-28656-5.

- Inalcik, Halil. The Ottoman Empire – The Classical Age 1300–1600. ISBN 1-84212-442-0.

- Iorga, Nicolae. Istoria lui Ştefan cel Mare, 1904 (new edition 1966), Bucharest.

- Matei, Mircea D.; Cârciumaru, Radu. Studii Noi Despre Probleme Vechi – Din Istoria Evului Mediu Românesc. Editura Cetatea de Scaun. ISBN 973-85907-2-8.

- Nevill Forbes; Arnold J. Toynbee; D. Mitrany, D.G. Hogarth. The Balkans: A History of Bulgaria, Serbia, Greece, Rumania, Turkey, 2004. ISO-8859-1.

- Samuelson, James. Roumania Past and Present, Chapter XI. Originally published London: Longmans, Green, and Co., 1882. Electronic text archive on the site of the Center for Advanced Research Technology in the Arts and Humanities, University of Washington.

- Sandberg-Diment, Erik. Artistic Route Through Romania, The New York Times, 1998.

- Sfântul Voievod Ştefan cel Mare, Chronicles. (retrieved)

- Angiolello, Giovanni Maria. Historia Turchesca.

- Bonfinius, Antonius. Historia Pannonica ab Origine Gentis AD Annum 1495.

- Curius, Joachim. Gentis Silesiæ Annales.

- Długosz, Jan. Historiae Polonicae, Leipzig, 1712.

- Husein, Kodja. Great Events.

- Murianus, Mathaeus. Letter to Leonardo Loredano, written on 7 December 1502.

- Orudj bin Adil and Şemseddin Ahmed bin Suleiman Kemal paşa-zade. The Chronicles of the Ottoman Dynasty.

- Pasha, Lütfi. The Chronicles of the House of Osman (Tevarih-i al-i Osman).

- Hoca Sadeddin Efendi. Crown of Histories (Tadj al-tawarikh).

- Stephen the Great; letter of 25 January 1475.

- Stryjkowski, Maciej. Kronika Polska, Litewska, Żmudzka i wszystkiej Rusi.

- Spinei, Victor. Moldavia in the 11th–14th Centuries, Romania, 1986.

- Panaite, Viorel. The Ottoman Law of War and Peace—The Ottoman Empire and Tribute Payers. ISBN 0-88033-461-4.

- Papacostea, Şerban. Relaţiile internaţionale ale Moldovei în vremea lui Ştefan cel Mare.

- Pippidi, Andrei. Noi Izvoare Italiene despre Vlad Ţepeş şi Ştefan cel Mare; Studies and Materials of Medium History XX/2002.

- Turnbull, Stephen. The Ottoman Empire 1326–1699. ISBN 1-84176-569-4.

- Ureche, Grigore and Costin, Nicolae. Letopiseţul, Ţărîi Moldovei.