| Battle of the Centaurs | |

|---|---|

| |

| Artist | Michelangelo |

| Year | c. 1492 |

| Type | Marble |

| Dimensions | 84.5 cm × 90.5 cm (33.3 in × 35.6 in) |

| Location | Casa Buonarroti |

| Preceded by | Madonna of the Stairs |

| Followed by | Crucifix (Michelangelo) |

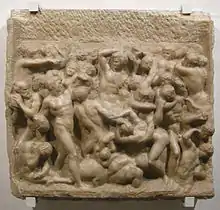

Battle of the Centaurs is a relief sculpture by the Italian Renaissance artist Michelangelo, created around 1492. It was the last work Michelangelo created while under the patronage of Lorenzo de' Medici, who died shortly after its completion. Inspired by a classical relief created by Bertoldo di Giovanni, the marble sculpture represents the mythic battle between the Lapiths and the Centaurs. A popular subject of art in ancient Greece, the story was suggested to Michelangelo by the classical scholar and poet Poliziano. The sculpture is exhibited in the Casa Buonarroti in Florence, Italy.

Battle of the Centaurs was a remarkable sculpture in several ways, presaging Michelangelo's future sculptural direction. Michelangelo had departed from the then current practices of working on a discrete plane to work multidimensionally. It was also the first sculpture Michelangelo created without the use of a bow drill and the first sculpture to reach such a state of completion with the marks of the subbia chisel left to stand as a final surface. Whether intentionally left unfinished or not, the work is significant in the tradition of "non finito" sculpting technique for that reason. Michelangelo regarded it as the best of his early works, and a visual reminder of why he should have focused his efforts on sculpture.

Background

Michelangelo, at 16, was working under the patronage of Lorenzo de' Medici when he sculpted the Battle of the Centaurs, although the work was not commissioned but created for himself.[1][2][3] The work reflected what was then a current fashion for reproducing ancient themes.[4] Specifically, Michelangelo was inspired by a relief that had been produced for Lorenzo by Bertoldo di Giovanni, a work in bronze that hung in the Medici palace.[4][5] Michelangelo chose to work in marble rather than the more expensive medium of bronze so as to keep down costs.[4] Bertoldo's work, The Equestrian Battle in the Ancient Manner—also known as Battle (with Hercules)—was a recreation of a damaged Roman battle sarcophagus and required liberal imagination to fill in the gaps left by the damaged original.[6] Bertoldo took other liberties with his source material and seems to have himself been inspired by the Antonio del Pollaiuolo engraving Battle of the Nudes.[4]

The young sculptor never finished the work.[7] While a number of biographies have attributed this to the loss of power of the Medici family, Eric Scigliano, a biographer of the sculptor, argues that Michelangelo had plenty of time to finish the sculpture if he had chosen to and points out that this was only the first of several "non finito" sculptures, preceding the Taddei Tondo and Pitti Tondo.[8] He also notes that Michelangelo expressed no dissatisfaction with the work.

Whether or not the sculpture was intentionally left incomplete, Michelangelo regarded this sculpture as the best of his early works.[1] He kept it for the rest of his life,[9] though he destroyed or abandoned many of his other pieces. He remarked to his biographer Ascanio Condivi that looking at it made him regret the time he had spent in pursuits other than sculpture.[10]

Subject and theme

According to Condivi, the poet Poliziano suggested the specific subject to Michelangelo, and recounted the story to him.[4] The battle depicted takes place between the Lapiths and the Centaurs at the wedding feast of Pirithous.[1] Pirithous, king of the Lapiths, had long clashed with the neighboring Centaurs. To mark his good intentions Pirithous invited the Centaurs to his wedding to Hippodamia (part of whose name, "Hippo," Ιππο, literally translates as "horse", which may suggest some connection to them).[11] Some of the Centaurs over-imbibed at the event, and when the bride was presented to greet the guests, she so aroused the intoxicated centaur Eurytion that he leapt up and attempted to carry her away.[12] This led not only to an immediate clash, but to a year-long war, before the defeated Centaurs were expelled from Thessaly to the northwest.

The myth was a popular subject for Greek sculpture and painting.[13] The Greek sculptors of the school of Pheidias perceived the battle of the Lapiths and Centaurs as symbolic of the great conflict between order and chaos and, more specifically, between the civilized Greeks and Persian "barbarians".[14] Battles between Lapiths and Centaurs were depicted in the sculptured friezes on the Parthenon and on the Temple of Zeus at Olympia.[15][16]

Scigliano suggests that Michelangelo's Battle of the Centaurs also reflects the themes of "Greeks over barbarians" and "civilization over savagery", but in Michelangelo's work he sees, in addition, the triumph of "stone over flesh".[10] He notes that in the work itself, Michelangelo depicts his combatants using rocks against one another, and suggests that the sculptor could not have missed the coincidence that the name of the human fighters—Lapith—reflects the Latin word for stone (lapis) and the Italian word for stone plaque (lapide).

Composition and technique

The fluidity of the twisting figure's limbs is a departure from the careful articulation of earlier Italian Renaissance sculpture.[7]

The relief consists of a mass of nude figures writhing in combat, placed underneath a roughed-out strip in which the artist's chisel marks remain visible. Art historian Howard Hibbard says that Michelangelo has obscured the centaurs, as most of the figures are represented from the waist up. Part of one of the few identifiable centaurs is visible in the bottom center, his leg extending between the legs of the twisting figure above him and his rump pinning another to the ground.

According to Hibbard, Michelangelo has obscured a lone female figure in the work.[17] The attempt to abduct Hippodamia had been the provocation for the brawl, however, and she is given a central location in the sculpture by Michelangelo. Her position balances the composition by placement similar to that of the twisted figure on the left. Her body also is twisting. They are equidistant from the edges of the composition. She is one of only two figures whose full body is displayed in the work. They both are displayed from head to toe. She can be seen among the figures in the center right, grasping the arm of one of her assailants, who has grabbed her hair. Her head, arms, back, hip, left leg, and left foot are displayed prominently. Another assailant, placed behind her, has his arm around her torso.

Battle of the Centaurs was an early turning point and a harbinger of Michelangelo's future sculptural technique.[2] The Michelangelo biographers, Antonio Forcellino and Allan Cameron, say that Michelangelo's relief, while created in a classical tradition, departed significantly from the techniques established by such masters as Lorenzo Ghiberti and Donatello.[18] Rather than working on discrete, parallel planes as his predecessors had done, Michelangelo carved his figures dynamically, within "infinite" planes. Forcellino and Cameron describe this break with modern practice as Michelangelo's "own personal revolution", and they point specifically to the left of the relief where a twisting figure becomes "something of an artistic manifesto."[19] Particularly striking is the composition of the figure's upper limbs, which deviate from the carefully articulated norms. Also remarkable, according to them, is the manner in which Michelangelo sculpted independently of his preparatory drawings, freeing him from the constraints of two-dimensional vision and allowing him to merge the figures fluidly and multi-dimensionally.[7]

Battle of the Centaurs was also the first sculpture for which Michelangelo eschewed the use of the bow drill.[1] Finer details of the relief were probably achieved with the use of a toothed chisel called a gradina.[8] The smooth figures of the foreground contrast strongly with the roughly hewn background, created with a subbia chisel.[1] A traditional sculptor's tool, the subbia produced punched marks that had never before been left as a final surface in a work completed to this degree.[8] Georgia Illetschko insisted in 2004, these unfinished surfaces are "a conscious compositional element", and not due to a lack of time.[20] According to Scigliano, it was an important development in the non finito sculpting technique.[8]

View from a left angle

View from a left angle Right side, detail

Right side, detail Men holding rocks

Men holding rocks Twisting figure on the left, right view

Twisting figure on the left, right view

See also

References

- 1 2 3 4 5 Cagno, Gabriella Di (March 2008). Michelangelo. The Oliver Press, Inc. p. 17. ISBN 978-1-934545-01-0. Retrieved 25 April 2010.

- 1 2 Kauffman, Mark (1964-07-17). "The Genius of Michelangelo". Life. p. 56. Retrieved 2010-04-25.

- ↑ Graham-Dixon, Andrew (2 February 2009). Michelangelo and the Sistine Chapel. Skyhorse Publishing Inc. p. 24. ISBN 978-1-60239-368-4. Retrieved 25 April 2010.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Richardson, Carol M. (2 March 2007). Locating Renaissance art. Yale University Press. p. 55. ISBN 978-0-300-12188-9. Retrieved 25 April 2010.

- ↑ Hibbard, Howard (1985). Michelangelo. Westview Press. p. 24. ISBN 978-0-06-430148-0. Retrieved 25 April 2010.

- ↑ Jay A. Levenson; National Gallery of Art (U.S.) (1991). Circa 1492: art in the age of exploration. Yale University Press. pp. 264–. ISBN 978-0-300-05167-4. Retrieved 25 April 2010.

- 1 2 3 Forcellino, Antonio; Allan Cameron (6 September 2009). Michelangelo: A Tormented Life. Polity. p. 33. ISBN 978-0-7456-4005-1. Retrieved 25 April 2010.

- 1 2 3 4 Scigliano, Eric (2005). Michelangelo's mountain: the quest for perfection in the marble quarries of Carrara. Simon and Schuster. p. 45. ISBN 978-0-7432-5477-9. Retrieved 25 April 2010.

- ↑ Coughlan, Robert (1966). The World of Michelangelo: 1475–1564. et al. Time-Life Books. p. 31.

- 1 2 Scigliano (2005), 44.

- ↑ Scigliano (2005), 43.

- ↑ Homerus; Alexander Pope; Thomas Parnell; Gilbert Wakefield (1796). The Odyssey. Longman. p. 79. Retrieved 25 April 2010.

- ↑ Tarbell, Frank Bigelow (1919). A history of Greek art: with an introductory chapter on art in Egypt and Mesopotamia. Macmillan. p. 174. Retrieved 25 April 2010.

- ↑ Kleiner, Fred S. (3 January 2008). Gardner's Art Through the Ages: A Global History. Cengage Learning. p. 144. ISBN 978-0-495-09307-7. Retrieved 25 April 2010.

- ↑ Jenkins, Ian; Ian Dennis Jenkins (2007). The Parthenon sculptures. Harvard University Press. p. 69. ISBN 978-0-674-02692-6. Retrieved 25 April 2010.

- ↑ Robertson, Martin (31 August 1981). A shorter history of Greek art. Cambridge University Press. p. 87. ISBN 978-0-521-28084-6. Retrieved 25 April 2010.

- ↑ Hibbard (1984), 24.

- ↑ Forcellino and Cameron (2009), 32.

- ↑ Forcellino and Cameron (2009), 32–33.

- ↑ Illetschko, Georgia (April 2004). I, Michelangelo. Prestel. p. 81. ISBN 3-7913-3079-9. Retrieved 25 April 2010.

External links

Media related to Battle of the Centaurs (Michelangelo) at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Battle of the Centaurs (Michelangelo) at Wikimedia Commons