| Operation Grapeshot | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the Italian Campaign of the Second World War | |||||||

British troops of the 5th (Huntingdonshire) Battalion, Northamptonshire Regiment, part of 11th Brigade of 78th Division, pick their way through the ruins of Argenta, 18 April 1945. | |||||||

| |||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

|

...and others |

| ||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

|

|

| ||||||

| Units involved | |||||||

| Strength | |||||||

|

Total: 1,333,856[4][nb 1] 5th Army: 266,883 fighting strength[4] Eighth Army: 632,980 fighting strength[5] |

Total: 585,000[6] | ||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||

|

16,258 casualties[nb 2] incl. 2,860 killed [7] | 30–32,000 casualties[nb 3] | ||||||

The spring 1945 offensive in Italy, codenamed Operation Grapeshot, was the final Allied attack during the Italian Campaign in the final stages of the Second World War.[8] The attack in the Lombard Plain by the 15th Allied Army Group started on 6 April 1945 and ended on 2 May with the surrender of German forces in Italy.

Background

The Allies had launched their last big offensive on the Gothic Line in August 1944, with the British Eighth Army (Lieutenant-General Oliver Leese) attacking up the coastal plain of the Adriatic and the U.S. Fifth Army (Lieutenant General Mark Clark) attacking through the central Apennine Mountains. Although they managed to breach the formidable Gothic Line defenses, the Allies failed to break into the Po Valley before the winter weather made further attempts impossible. The Allied forward formations spent the rest of the winter of 1944 in inhospitable conditions while preparations were being made for a spring offensive in 1945.

Command changes

When Field Marshal Sir John Dill, the head of the British Mission in Washington, D.C., died on 5 November, Field Marshal Sir Henry Maitland Wilson was appointed his replacement. General Harold Alexander, having been promoted to Field Marshal, replaced Wilson as Allied Supreme Commander Mediterranean on 12 December. Clark succeeded Alexander as commander of the Allied forces in Italy (renamed 15th Army Group), but without promotion. Lieutenant General Lucian Truscott, the commander of the U.S. VI Corps from the Battle of Anzio and the capture of Rome to Alsace, landed in the South of France during Operation Dragoon and returned to Italy to assume command of the Fifth Army.

On 23 March, Albert Kesselring was appointed Commander-in-Chief West, replacing General-Field Marshal Gerd von Rundstedt. Heinrich von Vietinghoff returned from the Baltic to take over from Kesselring and Traugott Herr, the experienced commander of the LXXVI Panzer Corps, took over the 10th Army. Joachim Lemelsen, who had temporarily commanded the 10th Army, returned to command the 14th Army.

Orders of battle

Allied manpower shortages continued in October 1944. The 4th Indian Infantry Division had been sent to Greece and the British 4th Infantry Division had followed them in November along with the 139th Brigade of the British 46th Infantry Division. The rest of the division followed in December along with the 3rd Greek Mountain Brigade. In early January 1945, the British 1st Infantry Division was sent to Palestine and at the end of the month the I Canadian Corps and the British 5th Infantry Division were ordered to north-west Europe. This reduced the Eighth Army, now commanded by Lieutenant-General Richard McCreery, to seven divisions. Two other British divisions were to follow them to north-west Europe, but Alexander kept them in Italy.

The U.S. Fifth Army had been reinforced between September and November 1944 with the 1st Brazilian Division, and in January 1945, with the specialist U.S. 10th Mountain Division.[9] Allied strength amounted to 17 divisions and eight independent brigades (including 4 Italian groups of volunteers from the Italian Co-Belligerent Army which were equipped and trained by the British), equivalent to just under 20 divisions. The 15th Army Group ration strength was 1,334,000 men, the Eighth Army having an effective strength of 632,980 men, and the Fifth Army 266,883.[5][4]

As of 9 April, the Axis in Italy had 21 much weaker German divisions and four Italian National Republican Army (ENR) divisions, with about 349,000 German and 45,000 Italian troops. There were another 91,000 German troops on the lines of communication, and Germans commanded about 100,000 Italian police.[10][6] Three of the Italian divisions were allocated to the Ligurian Army under Rodolfo Graziani which guarded the western flank facing France. Finally, the fourth division was with the 14th Army in a sector thought less likely to be attacked.[11]

Plan of attack

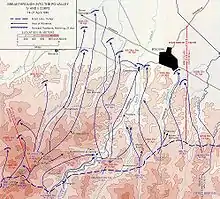

On 18 March, Clark set out his battle plan. Its objective was "to destroy the maximum number of enemy forces south of the Po, force crossings of the Po and capture Verona".[12] In Phase I, the Eighth Army would cross the Senio and Santerno rivers and then make a dual thrust, one towards Budrio parallel to the Bologna road, Route 9 (the Via Emilia) and the other northwest along Route 16, the Via Adriatica, towards Bastia and the Argenta Gap which was a narrow strip of dry terrain through the flooded land west of Lake Comacchio.

An amphibious operation across the lake and parachute drop would bring pressure to bear on the flank and help to break the Argenta position. Depending on the relative success of these actions, a decision would be made on whether the Eighth Army's prime objective would become Ferrara on the Via Adriatica or remain Budrio. The U.S. Fifth Army was to launch the Army Group's main effort at 24 hours notice from two days after the Eighth Army attack, and break into the Po valley. The capture of Bologna was looked upon as a secondary task.[12]

In Phase II, the Eighth Army was to drive northwest to capture Ferrara and Bondeno, blocking routes of potential retreat across the Po. The U.S. Fifth Army was to push past Bologna, north to link with Eighth Army in the Bondeno region, to complete an encirclement of German forces south of the Po. The Fifth Army was to make a secondary thrust further west towards Ostiglia, the crossing point on the Po of the main route to Verona.[13] Phase III involved the establishment of bridgeheads across the Po and exploitation north.

The Eighth Army plan (Operation Buckland) had to deal with the difficult task of getting across the Senio, with its raised artificial banks varying between 6 m (20 ft) and 12 m (40 ft) in height and honeycombed with tunnels and bunkers front and rear. V Corps was ordered to make an attack on the salient formed by the river into the Allied line at Cotignola. On the right of the river's salient was 8th Indian Infantry Division, reprising the role they played crossing the Rapido in the final Battle of Monte Cassino. To the left of the 8th Indian Division, on the left of the salient, the 2nd New Zealand Division would attack across the river to form a pincer. To the left of V Corps, on Route 9, the II Polish Corps would widen the front further by attacking across the Senio towards Bologna. The Poles had been desperately under strength in the autumn of 1944, but had received 11,000 reinforcements during the early months of 1945, mainly from Polish conscripts in the German Army taken prisoner in the Battle of Normandy .[14]

Once across the Senio, the assault divisions were to advance to cross the Santerno. Once the Santerno was crossed, the British 78th Infantry Division would reprise their Cassino role and pass through the bridgehead established by the Indians and New Zealanders and drive for Bastia and the Argenta gap, 23 km (14 mi) behind the Senio, where the dry land narrowed to a front of only 5 km (3 mi), bounded on the right by Lake Comacchio, a huge lagoon running to the Adriatic coast and on the left by a marshland. At the same time, the British 56th (London) Infantry Division would launch the amphibious flank attack along Lake Comacchio. On the left flank of V Corps, the New Zealand Division would advance to the left of the marshland on the west side of Argenta while the 8th Indian Infantry Division would pass in army reserve.[15]

The Fifth Army plan (Operation Craftsman) envisaged an initial thrust by IV Corps along Route 64 to straighten the army front and to draw German reserves away from Route 65. II Corps would then attack along Route 65 towards Bologna. The weight of the attack would then switch westward again to break into the Po valley skirting Bologna.[16]

Battle

In the first week of April, diversionary attacks were launched on the extreme right and left of the Allied front to draw German reserves away from the main assaults. Operation Roast was an assault by 2nd Commando Brigade and tanks to capture the seaward isthmus of land bordering Lake Comacchio and seize Port Garibaldi on the lake's north side. Damage to other transport infrastructure forced Axis forces to use sea, canal, and river routes for supply. During this time, Axis shipping was being attacked in bombing raids such as Operation Bowler.

The build-up to the main assault started on 6 April with heavy artillery bombardment of the Senio defenses. In the early afternoon of 9 April 825 heavy bombers dropped fragmentation bombs on the support zone behind the Senio followed by medium and fighter bombers. From 15:20 to 19:10, five heavy artillery barrages were fired each lasting 30 minutes, interspersed with fighter bomber attacks. In support of the New Zealand operations, 28 Churchill Crocodiles and 127 Wasp flamethrower vehicles were deployed along the front.[17][18] The 8th Indian Infantry Division, 2nd New Zealand Division, and 3rd Carpathian Division (on the Polish Corps front at Route 9) attacked at dusk. In the fight there were two Victoria Crosses won by the 8th Indian Infantry Division. They had reached the Santerno, 5.6 km (3.5 mi) beyond, by dawn on 11 April. The New Zealanders had reached the Santerno at nightfall on 10 April and succeeded in making a crossing at dawn on 11 April. The Poles had also closed on the Santerno by the night of 11 April.[19]

By late morning of 12 April, after an all-night assault, the 8th Indian Infantry Division was established on the far side of the Santerno and the 78th Infantry Division started their pass through to make the assault on Argenta. In the meantime, the 24th Guards Brigade, part of the 56th (London) Infantry Division, had launched an amphibious flanking attack from the water to the right of the Argenta Gap. Although they gained a foothold, they were still held up at positions on the Fossa Marina on the night of 14 April. The 78th Infantry Division was also held up that same day on the Reno River at Bastia.

The Fifth Army began its assault on 14 April after a bombardment by 2,000 heavy bombers and 2,000 guns along with attacks by IV Corps (1st Brazilian, 10th Mountain and 1st Armored Divisions) on the left. This was followed on the night of 15 April by II Corps attacking with 6th South African Armoured Division and the 88th Infantry Division advancing towards Bologna between Highway 64 and 65 and the 91st and 34th Infantry Divisions along Highway 65.[20]

Progress against a determined German defense was slow, but ultimately the superior Allied firepower and lack of German reserves allowed the Allies to break through the mountain defenses and reach the plains of the Po valley. The 10th Mountain Division was directed to bypass Bologna on the right and push north leaving II Corps to deal with Bologna, along with Eighth Army units advancing from their right.[21]

By 19 April, on the Eighth Army front, the Argenta Gap had been forced and the 6th Armoured Division was released through the left wing of the advancing 78th Infantry Division to swing left to race northwest along the line of the river Reno to Bondeno and link up with the Fifth Army to complete the encirclement of the German armies defending Bologna.[22]

On the same day, the Italian National Liberation Committee for Northern Italy, in command of the Italian resistance movement, ordered a general insurrection; in the following days, fighting between Italian partisan and the German and RSI forces broke out in Turin and Genoa (as well as in many other towns across Northern Italy), while German forces prepared to withdraw from Milan.[23] On all fronts, the German defense continued to be strong and effective, but Bondeno was captured on 23 April. The 6th Armoured Division linked with the 10th Mountain Division the next day at Finale some 5 mi (8.0 km) upstream along the river Panaro from Bondeno. Bologna was entered in the morning of 21 April by the 3rd Carpathian Infantry Division of the II Polish Corps and the Friuli Combat Group of the Italian Co-belligerent Army advancing up the line of Route 9, followed two hours later by II US Corps from the south.[24] On 24 April, Parma and Reggio Emilia were liberated by the partisans.[23]

IV Corps had continued its northwards advance and reached the Po river at San Benedetto on 22 April. The river was crossed the next day and they advanced north to Verona which they entered on 26 April. To the right of Fifth Army on Eighth Army's left wing, XIII Corps crossed the Po at Ficarolo on 22 April, while V Corps were crossing the Po by 25 April, heading towards the Venetian Line, a defensive line built behind the line of the river Adige.

As Allied forces pushed across the Po, on the left flank, the Brazilian Division, 34th Infantry Division, and 1st Armored Division of IV Corps were pushed west and northwest along the line of Highway 9 towards Piacenza and across the Po to seal possible escape routes into Austria and Switzerland via Lake Garda.[25][26] On 27 April, the 1st Armored Division entered Milan which had been liberated by the partisans on 25 April and the IV Corps commander Willis D. Crittenberger entered the city on 30 April.[23] Turin was also liberated by partisan forces on 25 April, after five days of fighting. On 27 April, General Günther Meinhold surrendered his 14,000 troops to the partisans in Genoa.[23] To the south of Milan, at Collecchio-Fornovo, the Brazilian Division bottled up the remaining effectives of two German divisions along with the last units of the National Republican Army, taking 13,500 prisoners on 28 April.[27] On the Allied far right flank, V Corps, met by lessened resistance, traversed the Venetian Line and entered Padua in the early hours of 29 April to find that partisans had locked up the German garrison of 5,000.[28]

Aftermath

.pdf.jpg.webp)

Secret surrender negotiations between representatives of the Germans and Western Allies had taken place in Switzerland (Operation Crossword) in March, but had resulted only in protests from the Soviets that the Western Allies were attempting to negotiate a separate peace. On 28 April, Vietinghoff sent emissaries to the Allied Army headquarters. On 29 April, they signed an instrument of surrender at the Royal Palace of Caserta stating that hostilities would formally end on 2 May.[28] Confirmation from Vietinghoff, did not reach the 15th Army Group headquarters until the morning of 2 May. It emerged that Kesselring had his authority as Commander of the West extended to include Italy and had replaced Vietinghoff with General Friedrich Schulz from Army Group G on hearing of the plans. After a period of confusion, during which the news of Hitler's death arrived, Schulz obtained Kesselring's agreement to the surrender and Vietinghoff was reinstated to see it through.[29]

On 1 May 1945, the Chief of Staff of the National Republican Army, Marshal Rodolfo Graziani, announced the unconditional surrender of the Italian Social Republic and ordered the forces under his command to lay down their arms. Lieutenant general Max-Josef Pemsel, Chief of General Staff of the Army Liguria, consisting of three German and three Italian divisions, followed Graziani's orders and declared in a broadcast message: "I confirm without reserve the words of my Commander, Marshal Graziani. You must obey his orders."[30]

See also

Notes

- ↑ Including lines of communication and support troops

- ↑ From 9 April 1945 until the end of Operation Grapeshot, thus casualties exclude those suffered during the preliminary operations.

5th Army: 7,965 casualties. American: 6,834 (1,288 killed, 5,453 wounded and 93 missing) casualties; South African: 537 (89 killed, 445 wounded and 3 missing) casualties; Brazilian: 594 (65 killed, 482 wounded and 47 missing) casualties.

8th Army: 7, 193 casualties. British: 3,068 (708 killed, 2,258 wounded and 102 missing) casualties; New Zealand: 1,381 (241 killed and 1,140 wounded) casualties; Indian: 1,076 (198 killed, 863 wounded and 15 missing) casualties; Colonial: 46 (11 killed and 35 wounded) casualties; Polish: 1,622 (260 killed, 1,355 wounded and 7 missing) casualties.

Italians fighting with both armies: 1,100 (242 killed, 828 wounded and 30 missing) casualties.[7] - ↑ British estimated around 30,000 casualties were inflicted upon the Axis forces during this offensive, while a German staff officer estimated 32,000 casualties suffered during Operation Grapeshot.[7]

References

- ↑ "Royal Artillery". www.heritage.nf.ca. Retrieved 20 May 2023.

- ↑ "Canada and the Italian Campaign". www.thecanadianencyclopedia.ca. Retrieved 20 May 2023.

- ↑ Canada, Veterans Affairs (23 June 2021). "Canada - Italy 1943-1945 - The Second World War - History - Remembrance - Veterans Affairs Canada". www.veterans.gc.ca. Retrieved 20 May 2023.

- 1 2 3 Jackson, p. 230.

- 1 2 Jackson, p. 223.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Jackson, p. 236.

- 1 2 3 Jackson, p. 334

- ↑ Jackson, p. 253

- ↑ Clark, 1950 pp. 607–609

- ↑ Blaxland, p. 242

- ↑ Blaxland, p. 243

- 1 2 Jackson, p. 203.

- ↑ Jackson, p. 204.

- ↑ Blaxland, p. 247

- ↑ Jackson, p. 225.

- ↑ Jackson, p. 228.

- ↑ Fletcher, Churchill Crocodile p. 35

- ↑ approximately one flamethrower vehicle every 70 yd (64 m) along an 5.0 mi (8 km)-long front

- ↑ Blaxland, pp. 256-258

- ↑ Popa, pp. 10–12

- ↑ Popa, p. 15

- ↑ Blaxland, pp. 267-8

- 1 2 3 4 Basil Davidson, Special Operations Europe: Scenes from the Anti-Nazi War (1980), pp. 340, 360

- ↑ Blaxland, p. 271

- ↑ Evans, Chapter 14 View on Google Books.

- ↑ Popa, p. 20

- ↑ Popa, p. 23

- 1 2 Blaxland, p. 277

- ↑ Blaxland, pp. 279-80

- ↑ "Graziani Announces Surrender". The New York Times. 2 May 1945.

Bibliography

- Blaxland, Gregory (1979). Alexander's Generals (the Italian Campaign 1944-1945). London: William Kimber & Co. ISBN 0-7183-0386-5.

- Böhmler, Rudolf (1964). Monte Cassino: a German View. London: Cassell. OCLC 2752844.

- Carver, Field Marshal Lord (2001). The Imperial War Museum Book of the War in Italy 1943–1945. London: Sidgwick & Jackson. ISBN 0-330-48230-0.

- Clark, Mark (2007) [1950]. Calculated Risk. Enigma Books. ISBN 978-1-929631-59-9.

- Doherty, Richard (2014). Victory in Italy: 15th Army Group's Final Campaign 1945. Pen & Sword Books. ISBN 978-1-78346-298-8.

- Evans, Bryn (2012) [1988]. With the East Surreys in Tunisia and Italy 1942–1945: Fighting for Every River and Mountain. The Rosen Publishing Group. ISBN 978-1-84884-762-0.

- Hingston, W. G. (1946). The Tiger Triumphs: The Story of Three Great Divisions in Italy. HMSO for the Government of India. OCLC 29051302.

- Jackson, W. G. F.; Gleave, T. P. (2004) [1988]. Butler, Sir James (ed.). The Mediterranean and Middle East: Part III - November 1944 to May 1945. History of the Second World War United Kingdom Military Series. Vol. VI (Naval & Military Press, Uckfield ed.). London: HMSO. ISBN 1-84574-072-6.

- Laurie, Clayton D. (c. 1990). Rome-Arno 22 January – 9 September 1944. WWII Campaigns. Washington DC: United States Army Center of Military History. CMH Pub 72-20. Archived from the original on 20 April 2011. Retrieved 1 July 2010.

- Muhm, Gerhard. "German Tactics in the Italian Campaign".

- Muhm, Gerhard (1993). La Tattica tedesca nella Campagna d'Italia, in Linea Gotica avanposto dei Balcani [German Tactics in the Italian Campaign, in the Gothic Line outpost of the Balkans] (in Italian) (Edizioni Civitas ed.). Roma: (Hrsg.) Amedeo Montemaggi.

- Oland, Dwight D. (1996). North Apennines 1944–1945. WWII Campaigns. Washington DC: United States Army Center of Military History. CMH Pub 72-34. Archived from the original on 22 December 2015. Retrieved 1 July 2010.

- Orgill, Douglas (1967). The Gothic Line (The Autumn Campaign in Italy 1944). London: Heinemann. OCLC 906106907.

- Popa, Thomas A. (1996). Po Valley 1945. WWII Campaigns. United States Army Center of Military History. ISBN 0-16-048134-1. CMH Pub 72-33. Archived from the original on 21 May 2011. Retrieved 1 July 2010.