| Bay of Fundy campaign | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of French and Indian War | |||||||

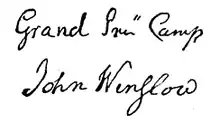

John Winslow, British commander | |||||||

| |||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

|

John Winslow Captain Alexander Murray |

Charles Deschamps de Boishébert et de Raffetot Joseph Broussard | ||||||

| Units involved | |||||||

| 40th Regiment of Foot |

Acadia militia Wabanaki Confederacy (Maliseet militia and Mi'kmaq militia) | ||||||

The Bay of Fundy campaign occurred during the French and Indian War (the North American theatre of the Seven Years' War) when the British ordered the Expulsion of the Acadians from Acadia after the Battle of Fort Beauséjour (1755). The campaign started at Chignecto and then quickly moved to Grand-Pré, Rivière-aux-Canards, Pisiguit, Cobequid, and finally Annapolis Royal. Approximately 7,000 Acadians were deported to the New England colonies.

Historical context

| Part of a series on the |

| Military history of Nova Scotia |

|---|

|

|

The British conquest of Acadia took place in 1710. Over the next 45 years the Acadians refused to sign an unconditional oath of allegiance to Britain. During this time period Acadians participated in various militia operations against the British, such as the raids on Dartmouth, Nova Scotia. The Acadians also maintained vital supply lines to the French Fortress of Louisbourg and Fort Beauséjour.[1] During the French and Indian War (the North American theatre of the Seven Years' War), the British sought both to neutralize any military threat the Acadians posed, and to interrupt the vital supply lines they provided to Louisbourg, by deporting them from Acadia.[2] Prior to the expulsion, the British retrieved the Acadians' weapons and boats in the Bay of Fundy region and arrested their deputies and priests.[3]

Campaign

Chignecto

After the fall of Fort Beauséjour (1755), the first wave of the expulsion of the Acadians began in the region of Chignecto. Under the direction of Colonel Robert Monckton, on August 10, Lieutenant-Colonel John Winslow seized four hundred unsuspecting men who were at Fort Cumberland (formerly Fort Beauséjour).[4] He also imprisoned 86 Acadians within Fort Lawrence.[5] The number of prisoners was one third of the men of the region; many of the others fled the region. The prisoners were kept in the fort until transports arrived to deport them. The wives and children joined them upon departure.[6]

Almost a month after the expulsion began, on September 2, Boishébert organized the Mi'kmaq and Acadian resistance in the region, and soundly defeated the British forces in the Battle of Petitcodiac. Almost one month later, on October 1, the Acadian prisoners at Fort Lawrence escaped. Joseph Broussard (Beausoleil) was one of the escapees.[5]

On October 13, a convoy of eight transports, carrying on board approximately 1782 prisoners, left Chignecto Basin escorted by three British men–of–war.[7] The Acadians of Chignecto were considered the most rebellious. As a result, they were sent the furthest from Acadia, to South Carolina and Georgia.[8] Upon leaving, Monckton began burning the Acadian villages to prevent the Acadians' return.[9]

On November 15, 1755, British officer John Thomas burned the village of Tentatmar (Sackville, New Brunswick), destroying in the process the church and ninety-seven other buildings.[10]

Cobequid

On August 15, under orders from Monckton, Captain Thomas Lewis, Abijah Willard and 250 troops began to destroy two villages in Cobequid: Tatamagouche and Remsheg (present-day Wallace, Nova Scotia).[11] The British chose to destroy these villages first in the expulsion because they were the gateway Acadians used to provide cattle and produce to Louisbourg.[12] Toward this end, Willard assembled the men of Tatamagouche in an Acadian home. He ensured that all the guns in the village were confiscated, and then notified the Acadian men that they were being taken prisoner. Willard immediately began to destroy the shipments of Acadian cattle and produce that were on vessels to be sent to Louisbourg.[13] On August 16, Lewis burned twelve homes and the chapel.[14] Willard continued to burn four houses and several barns in the early morning of August 17.[15]

Captain Lewis went with 40 men to Remsheg where he captured three families and burned several buildings.[14] Lewis returned to Fort Cumberland on August 26 with the Acadian male prisoners. The fate of the women and children of the region is unknown.[12]

On September 11, Captain Lewis was sent from Fort Cumberland to destroy the rest of the Cobequid, a region which included present-day Truro, Nova Scotia and stretched around to Petite Rivière (Walton, Nova Scotia) on the south shore of the Cobequid Bay, and Five Islands, Nova Scotia on the north shore.[16] Lewis discovered that the rest of Cobequid was vacant. Most of those in the region, such as Noël Doiron, had already vacated their farms over the previous five years and made their way to Ile Saint-Jean (Prince Edward Island).[16] From September 23–29th, Lewis laid waste to the countryside with fire.[17]

Grand Pré

On August 18, 1755,[18] eight days after Acadians were imprisoned at Chignecto, Lieutenant Colonel John Winslow arrived in Grand-Pré with 315 troops, and took up headquarters in the church. The 418 Acadian males (age 10 and older) of the area were ordered inside the church Saint-Charles-des-Mines on September 5, where they were unexpectedly imprisoned for five weeks.[19] Winslow informed them that all but their personal goods were to be forfeited to the Crown, and that they and their families were to be deported as soon as ships arrived to take them away. The wives were ordered to feed and clothe both the prisoners and the troops.[20] Six days after the initial imprisonment, because of fears of Acadian rebellion, Winslow moved 230 prisoners on board ships to await deportation.[21]

On October 13, more than 2000 Acadians had been loaded from the landing on the Gaspereau River to five transports anchored at the river's mouth.[22] Upon leaving, Winslow began burning the Acadian villages to prevent their return. He recorded that he burned 276 barns, 255 homes, 11 mills and one mass house in the villages surrounding Grand Pré.[9]

Piziquid

At exactly the same time as Winslow read the expulsion orders in Grand Pré, September 5 at 15:00 hrs, Captain Alexander Murray read the order to the 183 Acadian males he had imprisoned at Fort Edward.[23] On October 20, 920 Acadians from Piziquid were loaded on to four transports.[24] Unlike the neighbouring community of Grand Pré, the buildings at Pisiquid were not destroyed by fire. As a result, when the New England Planters arrived, many houses and barns still stood there.[25]

In April 1757, a band of Acadian and Mi'kmaq raided a warehouse near Fort Edward, killing thirteen British soldiers and, after taking what provisions they could carry, setting fire to the building. A few days later, the same militia also raided Fort Cumberland.[26]

While prisoners, the Acadians were made to assist the New England Planters with establishing their farmlands. When the war finished, rather than stay and work as subordinates, the Acadians settled with their compatriots in present-day New Brunswick and Saint Pierre and Miquelon.[27]

Annapolis Royal

At Annapolis Royal, Major John Handfield was responsible for expelling the Acadians.[28] The expulsion was slow to advance in this region, but finally on Dec 8, 1755 Acadians were embarked on seven vessels escorted by a man-of-war.[9] About three hundred Acadians are reported to have escaped deportation.[9]

_(cropped).jpg.webp)

The snow Edward was commanded by Ephraim Cook (mariner) and was lost months at sea before arriving in Connecticut.

Of the ships departing on December 8, 32 Acadian families (225 prisoners) on board the British ship Pembroke, bound for North Carolina, seized control of the vessel. On February 8, 1756, the Acadians had sailed up the Saint John River as far as they could.[30] The Acadians disembarked and burned their ship. A group of Maliseet met them and directed them upstream, where they joined an expanding Acadian community.[31] The Maliseet took them to one of Charles Deschamps de Boishébert et de Raffetot's refugee camps for the fleeing Acadians, which was at Beaubears Island.[32]

Some Acadian families further up the Annapolis River fled to forests on the North Mountain near Morden, Nova Scotia.[33] Many died in the winter that followed until a Mi'kmaw band helped survivors escape in the spring across the Bay of Fundy to Refugee Cove at Cape Chignecto and from there to the interior of New Brunswick.[34]

In December 1757, while cutting firewood near Fort Anne, John Weatherspoon was captured by Indians (presumably Mi'kmaq) and carried away to the mouth of the Miramichi River. From there he was eventually sold or traded to the French and taken to Quebec, where he was held until late in 1759 and the Battle of the Plains of Abraham, when General Wolfe's forces prevailed.[35]

About 50 or 60 Acadians who escaped the initial deportation are reported to have made their way to the Cape Sable region (which included south western Nova Scotia). From there, they participated in numerous raids on Lunenburg, Nova Scotia.[36]

Aftermath

By the end of the campaign, more than seven thousand Acadians had been deported to the New England States.[37] The French, Native and Acadians would conduct a guerrilla war against the British over the next four years, such as the raids on Lunenburg, Nova Scotia.[38] The second wave of the expulsion began after the siege of Louisbourg (1758). The British would then engage in the St. John River campaign, the Petitcodiac River campaign, the Ile Saint-Jean campaign, and the removal of Acadians in the Gulf of St. Lawrence campaign (1758).

See also

References

- ↑ Grenier (2008).

- ↑ Patterson, Stephen E. (1998). "Indian-White Relations in Nova Scotia, 1749-61: A Study in Political Interaction". In P.A. Buckner; Gail G. Campbell; David Frank (eds.). The Acadiensis Reader: Atlantic Canada Before Confederation (3rd ed.). Acadiensis Press. pp. 105-106. ISBN 978-0-919107-44-1.

• Patterson, Stephen E. (1994). "1744–1763: Colonial Wars and Aboriginal Peoples". In Phillip Buckner; John G. Reid (eds.). The Atlantic Region to Confederation: A History. University of Toronto Press. p. 144. ISBN 978-1-4875-1676-5. JSTOR 10.3138/j.ctt15jjfrm. - ↑ Faragher (2005), p. 340.

- ↑ Faragher (2005), p. 338.

- 1 2 Faragher (2005), p. 356.

- ↑ Faragher (2005), p. 339.

- ↑ Faragher (2005), p. 357.

- ↑ Faragher (2005), p. 335.

- 1 2 3 4 Faragher (2005), p. 363.

- ↑ Grenier (2008), p. 184.

- ↑ Patterson (1934), p. 69; also see Willard's Journal published in NB Historical Society no. 12 by John Clarence Webster.

- 1 2 Patterson (1934), p. 75.

- ↑ Patterson (1934), pp. 72, 76.

- 1 2 Patterson (1934), p. 72.

- ↑ Patterson (1934), p. 73.

- 1 2 S. Scott and T. Scott, "Noel Doiron and the East Hants Acadians", Journal of the Royal Nova Scotia Historical Society, Vol. 11, 2008

- ↑ Patterson (1934), p. 77.

- ↑ Plank (2001), p. 146.

- ↑ Plank (2001), p. 147.

- ↑ Faragher (2005), p. 346.

- ↑ Faragher (2005), p. 354.

- ↑ Faragher (2005), p. 361; Plank (2001), p. 149

- ↑ Faragher (2005), pp. 140, 346.

- ↑ Faragher (2005), p. 361.

- ↑ Gwyn, Julian. Planter Nova Scotia 1760–1815: New Port Township. Wolfville: Kings-Hants Heritage Connection. 2010. p. 23

- ↑ Faragher (2005), p. 398.

- ↑ Plank (2001), p. 164.

- ↑ Faragher (2005), p. 336.

- ↑ Diary of John Thomas, surgeon in Winslow's expedition of 1755 against the Acadians (1879)

- ↑ Les Cahiers de la Societe historique acadienne vol. 35, nos. 1&2 (Jan-Jun 2004)

- ↑ Plank (2001), p. 150.

- ↑ Grenier (2008), p. 186.

- ↑ Faragher (2005), p. 348.

- ↑ "Park History", Cape Chignecto Provincial Park website

- ↑ John Witherspoon, Journal of John Witherspoon, Collections of the Nova Scotia Historical Society, Vol 2, pp. 31–62.

- ↑ Winthrop Bell, Foreign Protestants, University of Toronto. 1961. p.503

- ↑ Faragher (2005), p. 364.

- ↑ For the Guerrilla War see Grenier (2008). For the Raid on Lunenburg (1756) see Linda G. Layton. (2003) A passion for survival: The true story of Marie Anne and Louis Payzant in Eighteenth-century Nova Scotia. Nimbus Publishing.

Primary sources

- Winslow's Journal – Bay of Fundy Campaign (1755)

- Diary of John Thomas, surgeon in Winslow's expedition of 1755 against the Acadians (1879)

- Journal of Jeremiah Bancroft

- Brook Watson's account (1791)

- Lawrence to Monckton August 1755,The Historical Magazine, and Notes and Queries Concerning the Antiquities, History, and ... (1860), p. 41

- Journal of Abijah Willard, 1755

Further reading

- Dunn, Brenda (2004). A history of Port Royal/Annapolis Royal, 1605–1800. Nimbus Pub. ISBN 978-1-55109-484-7.

- Griffiths, N.E.S. (2005). From Migrant to Acadian: A North American Border People, 1604-1755. McGill-Queen's University Press. ISBN 978-0-7735-2699-0.

- Grenier, John (2008). The Far Reaches of Empire: War in Nova Scotia, 1710–1760. University of Oklahoma Press. ISBN 978-0-8061-3876-3.

- Faragher, John Mack (2005). A Great and Noble Scheme: The Tragic Story of the Expulsion of the French Acadians from Their American Homeland. W.W Norton & Company. ISBN 978-0-393-05135-3.

- Patterson, Frank H. (1934). Old Cobequid and Its Destruction. Halifax, Nova Scotia: Nova Scotia Historical Society.

- Basque, Maurice; Mancke, Elizabeth; Reid, John G. (2004). Reid, John G.; Basque, Maurice; Mancke, Elizabeth; et al. (eds.). The "Conquest" of Acadia, 1710: Imperial, Colonial, and Aboriginal Constructions. University of Toronto Press. doi:10.3138/9781442680883. ISBN 978-0-8020-8538-2. JSTOR 10.3138/9781442680883.

- Plank, Geoffrey (2001). An Unsettled Conquest: The British Campaign Against the Peoples of Acadia. University of Pennsylvania Press. ISBN 978-0-8122-0710-1.

.jpg.webp)