| |||||||||||||||||||||||||

All 177 seats in the Illinois House of Representatives 89 seats needed for a majority | |||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||

Composite vote by county

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Elections in Illinois |

|---|

|

An election for all 177 members of the Illinois House of Representatives for the 74th Illinois General Assembly was held on November 3, 1964, alongside the other 1964 Illinois elections to state and federal offices. Due to the state's failure to redistrict, all of the seats were elected at-large, with voters choosing 177 candidates to support. Each party was only allowed to nominate 118 candidates. All 118 Democratic candidates won, flipping control of the chamber to Democrats with a two-thirds supermajority.

Since 1901, the state had failed to conduct legislative redistricting until 1954, at which point a constitutional amendment to force regular redistricting of the House was passed. In the case of the legislature failing to redistrict, a redistricting commission would be created, and if that were to also fail to produce a map, an election would be held at-large.

For the 1960 redistricting cycle, the state's governor was Democrat Otto Kerner Jr., while both chambers of the legislature were controlled by Republicans. Due to population shifts, Chicago was due to lose districts to its suburbs. Democrats insisted on drawing districts that overlapped between Chicago and its suburbs, while Republicans refused to do so. Kerner vetoed the legislature's map, and the commission deadlocked along partisan lines. Following a ruling by the state supreme court, an at-large election was held.

The ballot for the election was 33 inches (84 cm) long. Candidates for the election were selected at each party's convention, which were made up of delegates elected on the old legislative lines. Candidates did little campaigning outside of their home regions. Due to straight-ticket voting and the coattails of Lyndon B. Johnson in the concurrent presidential election, every Democrat was elected, receiving more votes than every Republican. The Republicans elected were mainly those endorsed by Chicago-area newspapers.

Reactions to the election were mixed. Both political parties received significant criticism for their failure to redistrict. There were expectations of widespread voter confusion before the election, and a high number of undervotes, but this did not happen. The legislature elected in 1964 pushed for governmental reform, starting the process that eventually led to the 1970 rewrite of the Constitution of Illinois. This election is the only time a state legislature has been elected at-large in the United States.

Background

Constitutional procedure

Prior to the 1960s, Illinois had only redistricted its House of Representatives once since 1901. While the Constitution of Illinois stated that the legislature was required to redistrict the state, it did not provide any method of enforcement if the legislature did not. Population shifts in the state had resulted in Chicago having a higher percentage of the state's population, and downstate legislators did not want their region of the state to lose influence. Therefore, starting in the cycle after the 1910 United States census, legislators chose not to redistrict the state, with courts choosing not to intervene to force redistricting.[2]: 291–292 A constitutional convention, approved by voters in 1918, aimed to deal with the issue,[3]: 443 but voters rejected its proposed constitution in 1922.[2]: 291–292 The 1901 legislative map had 51 districts, with 19 located in Cook County.[2]: 291 [lower-alpha 2]

As the population of Chicago and Cook County grew, the level of malapportionment continued to increase. In the 1930 United States census, Cook County contained a majority of the state's population, but it continued to contain only 37.3% of the state's legislative districts.[2]: 294 Throughout the 1920s and 1930s, residents of the Chicago area, most notably John B. Fergus and John W. Keogh, argued before both state and federal courts in unsuccessful attempts to force redistricting.[2]: 292–294 In the 1930s, there were various efforts supported by governors Louis L. Emmerson and Henry Horner to allow Cook County proportional representation in either the Illinois House of Representatives or the Illinois Senate, while limiting its representation in the other, but these proposals died due to strong bipartisan opposition from downstate politicians.[2]: 294–295

By 1953, William Stratton, the newly elected governor of Illinois, viewed redistricting as a priority amidst increasing public pressure over malapportionment. Through a number of compromises, he managed to convince the legislature to pass a constitutional amendment to establish new redistricting procedures. The amendment allotted the 58 districts of the Illinois Senate into three areas: 18 to Chicago, 6 to Cook County, and 34 to downstate. The amendment, written to keep the Senate in downstate control, did not provide for periodic reapportionment of the Senate, intending to lock in the districts drawn in 1954 indefinitely, but it did provide that for the House's 59 districts, requiring redistricting after every decennial U.S. census. Initially, 23 districts would be assigned to Chicago, 7 to suburban Cook County, and 29 to downstate.[2]: 296–297 To ensure regular reapportionment, the constitution contained two separate procedures for if the legislature failed to redistrict. First, redistricting would be done by a ten-member commission, with five members appointed from each political party by the governor. If that commission failed to create districts after four months, an at-large election would be held.[2]: 297

Opposition to the amendment was disorganized, while supporters included many state politicians and newspapers. The new redistricting process was approved by voters in a 1954 referendum with about 80% of the vote.[2]: 297–298 Following the passage of the amendment, new districts were drawn in 1955. At this time, both chambers were Republican-controlled, as was the governorship, leading to a relatively non-controversial redistricting cycle. Each chamber created their own map, and passed the proposed map of the other chamber, with the maps being signed by Stratton. The map used for the House of Representatives map was fairly apportioned, while the Senate's map still retained significant malapportionment. However, the maps were overall considered a significant improvement.[2]: 298

1960 redistricting cycle

Following the 1962 elections, Republicans controlled both chambers of the legislature, albeit with a one-seat majority in the House. Governor Otto Kerner Jr., however, was a Democrat, resulting in a divided government. Redistricting for the House was required to take place before the 1964 elections.[4][5]: 380 In data from the 1960 census, the state's population had shifted towards suburbs of Chicago, particularly in Cook County, Lake County, and DuPage County. Using population-based apportionment, two districts would be shifted from Chicago to the suburbs, and two more from southern Illinois to northeastern Illinois.[2]: 298 On April 23, Republicans in the legislature introduced a plan to that effect. Democrats responded on the same day with a plan to instead have districts that would include parts of both Chicago and its suburbs, allowing the city to have control of 23 districts, arguing that this was fair given Chicago's under-representation in the Senate.[2]: 299

Democrats received no Republican support for their redistricting plan, while Republicans failed to pass their plan over southern Illinois lawmakers in their caucus, who objected to the plan's proposed removal of two districts from their area. As a compromise, Republicans passed a plan that would only remove one district from there, at the expense of a district planned for Lake County.[2]: 299 However, this bill was vetoed by Kerner on July 1, as he deemed it "unfair".[2]: 299 [4] Kerner had previously promised to veto any partisan redistricting plan, and his veto message referred to the deliberate under-representation of Republican areas (which occurred as a result of the compromises made to appease downstate lawmakers). Kerner's veto was challenged at the Supreme Court of Illinois, where it was upheld. The failure of the legislature to redistrict caused the responsibility to fall to the backup commission.[2]: 299

Special commission deadlock

Each party's state central committee nominated ten candidates for the redistricting commission. Kerner appointed five from each party on August 14, 1963.[2]: 299 The five Democrats appointed were George Dunne, finance chairman (and future president) of the Cook County Board of Commissioners; Ivan Elliott, former Illinois Attorney General; Alvin Fields, mayor of East St. Louis; Daniel Pierce, a member of the Democratic state central committee; and James Ronan, the chairman of the Democratic state central committee. The five Republicans appointed were Edward Jenison, a former congressman; David Hunter, a former state legislator; Michael J. Connolly, the Republican leader in Chicago's 5th Ward; Eldon Martin, an attorney from Wilmette; and Fred G. Gurley, former president of the Atchison, Topeka and Santa Fe Railway.[6] Dunne served as the Democratic spokesman on the commission, while Gurley served as the Republican spokesman.[7] Kerner avoided appointing some of the more prominent politicians who parties nominated for the commission: he did not appoint former governor Stratton, nominated by Republicans, and did not appoint Paul Powell, the Democratic minority leader in the House, or John Touhy, the Democratic minority whip.[6]

The redistricting commission deadlocked over a similar issue to what prevented a bipartisan map from passing the legislature – namely, the number of districts in Chicago. Democrats on the commission argued for maintaining 23 districts in Chicago, and refused to accept a map with less than 22, while Republicans would only accept a map with 21 districts in the city, with two districts being moved to the Cook County suburbs.[2]: 300 [8] Starting on November 14, the Republicans on the commission began boycotting the meetings due to Democrats' insistence that Chicago control 23 districts.[7] Republicans only started attending the meetings again on December 12, two days before the final deadline to agree on a new map.[7] Negotiations continued up until the deadline, with Democrats eventually proposing a map with only 22 Chicago-based districts, but the commission was ultimately unsuccessful in reaching a compromise.[2]: 300 [4][7]

Court rulings and special legislative session

Before the commission's ultimate failure to create maps, Republican state representative Gale Williams sued to overturn Kerner's veto of the legislative map, arguing that the governor had no authority to veto a redistricting bill. Kerner's actions were defended by the Illinois Attorney General, William G. Clark. This lawsuit was initially dismissed in Sangamon County Circuit Court before being appealed to the state's Supreme Court, which also ruled against Williams.[2]: 299 [9]

Two lawsuits were decided by the Supreme Court on January 4, 1964.[10][2]: 300 First, a lawsuit was filed by Republican state representative Fred Branson that challenged the legality of the commission, arguing that since the legislature had not "failed to act" on redistricting, as they had passed a map, a commission could not be established. This lawsuit instead requested that the election be held using the previous redistricting cycle's map.[11] The court rejected this argument, ruling that an at-large election had to take place.[10] Secondly, a lawsuit was filed by Chicago lawyer Gus Giannis arguing that an at-large election also had to take place for the State Senate.[10] In response to this case, Attorney General Clark issued a ruling stating that an at-large election would be required for the Senate as well.[12] The Supreme Court rejected this argument, ruling that the constitution would only mandate an at-large election for the Senate if the chamber had not been redistricted in 1956, as the constitution did not otherwise require the Senate to be redistricted.[13][2]: 300

Following the court's decisions, Kerner called a special session of the legislature on January 6 to set up procedures for the at-large election.[14] Kerner proposed procedures for the election, and these were passed with slight modification by the legislature. Notably, Illinois's practice of cumulative voting for the House of Representatives was suspended, and instead minority party representation was guaranteed by only allowing each party to nominate 118 candidates for the 177 seats available.[2]: 301–302 [15] The bill was signed by Kerner on January 29 after it passed 161–0 in the House and 46–6 in the Senate.[2]: 302

Election procedure and campaign

The emergency bill passed by the legislature in the special session allowed each party to nominate up to 118 candidates at their party convention.[14] Delegates to each party's convention were elected using the previous districts during the state's April primary.[2]: 301–302 The House recommended that each party nominate 100 candidates, to protect incumbent House members and ensure the minority party would have at least 77 seats.[14] Third-party and independent candidates could also run, though they needed to gather 25k signatures to make the ballot.[16]

The election was held on November 3, 1964, as part of the 1964 Illinois elections.[2]: 289

Candidate selection

Both the Democratic and Republican conventions were held on June 1 in Springfield. The Republican convention, held at a local Elks Club building, was controlled by delegates loyal to Charles H. Percy, the party's candidate for governor. Delegates loyal to Percy refused to renominate nine incumbent legislators from the Chicago area, a part of the so-called "West Side bloc", who were viewed as loyal to the Democratic political machine in Cook County.[2]: 302 [17] In the end, 70 Republican incumbents were renominated. The Democratic convention, held at the St. Nicholas Hotel, delegated the responsibility for preparing a slate of candidates to an executive committee. The convention met again on June 20 to approve the candidates; all 68 incumbents who chose to run were renominated with little controversy. Both parties nominated slates of 118 candidates in total.[2]: 302–303

There were multiple attempts to run a "Third Slate" of candidates. The Better Government Association of Chicago, along with some downstate politicians, presented a "blue ribbon" slate of candidates. However, with both parties putting up what were deemed to be acceptable slates of candidates, and Republicans choosing not to renominate the West Side bloc and nominating some blue ribbon candidates instead, this Third Slate effort disbanded.[17][18]

Another attempt to put a Third Slate on the ballot was backed by various civil rights groups and labor unions, including the United Auto Workers.[19] Their planned platform focused on election reform and civil rights. The Third Slate intended on nominating 59 candidates, allowing a voter to straight-ticket vote for the slate as well as one of the two major parties.[20] However, this Third Slate failed to make the ballot, with the state's election board ruling on August 21 that they had failed to gather the 25k signatures necessary.[21]

Popular names were picked to run on each party's ticket. Democrats nominated Adlai Stevenson III, the son of Adlai Stevenson II (a popular former governor), and John A. Kennedy, a businessman with a similar name (but no relation) to president John F. Kennedy, who had been murdered the previous year. Republicans ran Earl D. Eisenhower, the brother of popular former president Dwight D. Eisenhower.[18]

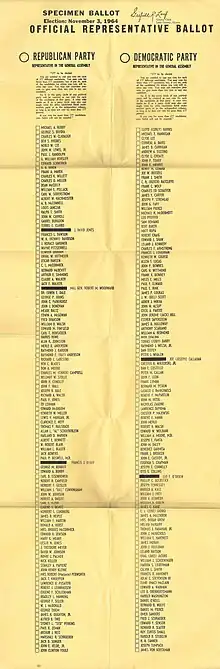

Ballot

The ballot for the State House election was separate from the ballot for other concurrent elections. Voters were allowed to cast up to 177 votes, with a straight-ticket voting option available to vote for all 118 candidates of a party's slate. Voters who voted straight-ticket could also vote for up to 59 candidates from the other party. Both parties recommended utilizing straight-ticket voting.[22] The ballot was 33 inches (84 cm) long and was often referred to as the "bedsheet ballot".[18]

Both parties used the same ordering when listing their candidates on the ballot. Incumbent legislators were placed at the top, ordered by seniority, alternating between candidates from Cook County and downstate. The remaining candidates were then listed, also alternating between Cook County and downstate candidates.[2]: 306

There were four ballots given to voters in 1964: a white ballot, containing most of the typical races (such as for president and governor); a green ballot, voting on the retention elections for various judges; a blue ballot, containing two constitutional amendments to be voted on; and the orange ballot, solely reserved for the House of Representatives election. Before the election, the sheer number of ballots to be voted on led to predictions of a high number of undervotes in the House of Representatives election, but post-election analysis revealed that this did not take place.[2]: 303

Campaigning and endorsements

Both parties encouraged a straight-ticket vote. Republicans explicitly discouraged voting for any Democratic candidates, arguing that voting for Democrats would cause the legislature to become controlled by Richard J. Daley, the mayor of Chicago. Democrats argued that a straight-ticket vote would "ensure representation from every district in Illinois".[2]: 303 Individual candidates for the legislature generally avoided campaigning across the state, instead only campaigning around their home region, if at all.[2]: 303 [18]

Many newspapers endorsed a partisan slate. The Field Enterprises newspapers,[lower-alpha 3] the Chicago Tribune, the Champaign News-Gazette, and the Illinois State Journal endorsed the Republican slate. However, the Illinois State Register, which was, like the Illinois State Journal, under Copley ownership, had a different editorial team and endorsed the Democratic slate.[23] Given the unique electoral system allowing voters to vote for candidates of both parties, some newspapers made bipartisan endorsements of candidates, either in addition to their partisan endorsements, or without making an overall partisan endorsement.[23] The Lindsay-Schaub group[lower-alpha 4] of newspapers endorsed 48 Democrats and 48 Republicans after sending a questionnaire to all candidates in the election, suggesting voters to vote straight-ticket and for all of the newspaper's endorsed candidates of the opposing party.[23][17] Likewise, the Daily Herald, a newspaper serving the suburbs of Chicago, endorsed seven candidates (four Republicans and three Democrats) who they believed had a good understanding of suburban issues.[24]

Results

Reporting

Results were not known immediately after the election; while the results in other statewide races were known on November 4, the statewide tally and canvass for the House elections took multiple weeks.[25] Based on early reported returns in some downstate precincts, Democrats declared victory on November 4, predicting that they had elected their entire slate. However, Republicans did not yet concede, believing they still had a chance of victory.[26] Cook County's results were fully counted by November 9, though not reported until later.[27] Unofficial results for 100 downstate counties, excluding Cook and DuPage, were reported on November 26, showing a strong performance by Democrats.[28] Unofficial statewide results were reported on December 3, showing that every Democratic candidate had won, with many Republican incumbents losing re-election.[29]

Five Republican candidates[lower-alpha 5] obtained an injunction over the results in DuPage County, claiming that there were more votes cast than voters registered in five precincts.[31] The injunction was issued by circuit judge Philip Locke on November 30. After the release of statewide results, it became apparent that the discrepancies would not affect the overall balance of power in the legislature.[32] On December 14, Democratic Attorney General William G. Clark filed a motion to move the case to the Illinois Supreme Court, to force the vote count to be released. The Illinois Supreme Court acted on this on January 6, 1965, releasing the DuPage results only hours before legislators were sworn in. Locke interpreted the Supreme Court's order as allowing him to order recounts in certain precincts, which he did. The recounts found only minor errors with no significant impact on the results.[33]

Analysis

Straight-ticket votes elected Democrats to the majority, with every Democrat receiving more votes than any Republican, resulting in the election of all 118 Democratic candidates.[2]: 305 The strong Democratic performance was attributed to coattails from Democratic president Lyndon B. Johnson's victory over Republican Barry Goldwater in the 1964 United States presidential election in Illinois.[18] However, voters who did not only vote straight-ticket had a significant impact as well: they determined the 59 Republicans who were elected, as well as the order of the winning Democratic candidates.[2]: 306

Contrary to many preelection predictions, voting was not driven by ballot order, with little correlation between where candidates were placed on the ballot and how many votes they received. The top-placing Democrat was Adlai E. Stevenson III, while the top-placing Republican was Earl D. Eisenhower. Both were listed on the bottom half of their respective side of the ballot (Stevenson was the 102nd Democratic candidate listed, and Eisenhower 79th Republican).[2]: 306 The results were strongly influenced by endorsements. In downstate Illinois, these were mainly those of the Illinois Agricultural Association and the Illinois AFL-CIO, as well as the Lindsay-Schaub group[lower-alpha 4] of downstate newspapers. However, the election was mainly decided in Chicago and its suburbs, where the endorsements of the Chicago American and the Field Enterprises newspapers[lower-alpha 3] were mostly responsible for the results.[2]: 306

Among the Democrats elected, 68 were incumbents while 50 were new members, and among the Republicans, 31 were incumbents and 28 were new members. 37 incumbent Republicans who ran for reelection lost their seats.[2]: 307 Geographically, candidates living in Cook County won a narrow majority of seats. About half of counties had no representatives, and a majority of representatives from both Cook County and from downstate were Democrats.[2]: 307 [lower-alpha 6]

| Party | Candidate | Votes | % | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Democratic | Adlai E. Stevenson III | 2,417,978 | 0.46% | |

| Democratic | John K. Morris (incumbent) | 2,410,365 | 0.46% | |

| Democratic | Anthony Scariano (incumbent) | 2,385,622 | 0.45% | |

| Democratic | John P. Touhy (incumbent) | 2,378,228 | 0.45% | |

| Democratic | Abner J. Mikva (incumbent) | 2,377,439 | 0.45% | |

| Democratic | William A. Redmond (incumbent) | 2,371,134 | 0.45% | |

| Democratic | Joseph T. Connelly | 2,369,556 | 0.45% | |

| Democratic | John E. Cassidy, Jr. | 2,368,063 | 0.45% | |

| Democratic | John A. Kennedy | 2,367,755 | 0.45% | |

| Democratic | Bernard M. Peskin (incumbent) | 2,367,287 | 0.45% | |

| Democratic | Chester P. Majewski (incumbent) | 2,366,785 | 0.45% | |

| Democratic | Daniel M. Pierce | 2,364,469 | 0.45% | |

| Democratic | James P. Loukas (incumbent) | 2,363,338 | 0.45% | |

| Democratic | Esther Saperstein (incumbent) | 2,361,847 | 0.45% | |

| Democratic | Mrs. Dorah Grow | 2,360,574 | 0.45% | |

| Democratic | Harold D. Stedelin | 2,358,491 | 0.45% | |

| Democratic | Lloyd (Curly) Harris (incumbent) | 2,357,709 | 0.45% | |

| Democratic | Paul F. Elward (incumbent) | 2,357,524 | 0.45% | |

| Democratic | William E. Hartnett | 2,356,700 | 0.45% | |

| Democratic | Marvin S. Lieberman | 2,356,576 | 0.45% | |

| Democratic | Robert E. Mann (incumbent) | 2,356,342 | 0.45% | |

| Democratic | Harold A. Katz | 2,355,168 | 0.45% | |

| Democratic | James Moran | 2,354,684 | 0.45% | |

| Democratic | Cecil A. Partee (incumbent) | 2,351,757 | 0.45% | |

| Democratic | Eugenia S. Chapman | 2,351,257 | 0.45% | |

| Democratic | Raymond J. Welsh, Jr. (incumbent) | 2,349,573 | 0.45% | |

| Democratic | Joe (Joseph) Callahan | 2,348,350 | 0.45% | |

| Democratic | J. W. (Bill) Scott (incumbent) | 2,343,772 | 0.45% | |

| Democratic | William Pierce (incumbent) | 2,341,983 | 0.45% | |

| Democratic | James C. Kirie | 2,340,388 | 0.45% | |

| Democratic | Edward A. Warman | 2,340,263 | 0.45% | |

| Democratic | Leland Rayson | 2,339,745 | 0.45% | |

| Democratic | E. J. (Zeke) Giorgi | 2,339,506 | 0.45% | |

| Democratic | Phillip C. Goldstick | 2,337,565 | 0.44% | |

| Democratic | John Merlo (incumbent) | 2,337,425 | 0.44% | |

| Democratic | Allen T. Lucas (incumbent) | 2,333,588 | 0.44% | |

| Democratic | James A. McLendon | 2,332,951 | 0.44% | |

| Democratic | John M. Daley | 2,332,665 | 0.44% | |

| Democratic | Leland J. Kennedy (incumbent) | 2,331,981 | 0.44% | |

| Democratic | Paul E. Rink (incumbent) | 2,331,722 | 0.44% | |

| Democratic | James D. Carrigan (incumbent) | 2,330,860 | 0.44% | |

| Democratic | Joe W. Russell (incumbent) | 2,330,466 | 0.44% | |

| Democratic | Melvin McNairy | 2,328,466 | 0.44% | |

| Democratic | Harold Washington | 2,328,125 | 0.44% | |

| Democratic | John Jerome (Jack) Hill (incumbent) | 2,328,023 | 0.44% | |

| Democratic | Clyde Lee (incumbent) | 2,326,629 | 0.44% | |

| Democratic | Clyde L. Choate (incumbent) | 2,324,383 | 0.44% | |

| Democratic | Charles Ed Schaefer (incumbent) | 2,324,100 | 0.44% | |

| Democratic | James D. Holloway (incumbent) | 2,323,732 | 0.44% | |

| Democratic | Chester R. Wiktorski, Jr. (incumbent) | 2,321,044 | 0.44% | |

| Democratic | Robert V. Walsh (incumbent) | 2,320,956 | 0.44% | |

| Democratic | William J. Schoeninger | 2,320,724 | 0.44% | |

| Democratic | James Von Boeckman | 2,320,580 | 0.44% | |

| Democratic | Roy Curtis Small | 2,320,211 | 0.44% | |

| Democratic | C. R. (Butch) Ratcliffe (incumbent) | 2,318,456 | 0.44% | |

| Democratic | Joseph P. Stremlau (incumbent) | 2,316,029 | 0.44% | |

| Democratic | Francis X. Mahoney | 2,315,855 | 0.44% | |

| Democratic | Carl H. Wittmond (incumbent) | 2,315,638 | 0.44% | |

| Democratic | Miles E. Mills (incumbent) | 2,315,065 | 0.44% | |

| Democratic | Elmo (Mac) McClain | 2,314,645 | 0.44% | |

| Democratic | Corneal A. Davis (incumbent) | 2,313,943 | 0.44% | |

| Democratic | Robert Craig (incumbent) | 2,313,925 | 0.44% | |

| Democratic | Tobias (Toby) Barry (incumbent) | 2,312,923 | 0.44% | |

| Democratic | Fred J. Schraeder | 2,312,797 | 0.44% | |

| Democratic | William A. Moore, M.D. | 2,311,742 | 0.44% | |

| Democratic | Bert Baker (incumbent) | 2,311,412 | 0.44% | |

| Democratic | Leo F. O'Brien | 2,309,250 | 0.44% | |

| Democratic | John J. McNichols | 2,306,601 | 0.44% | |

| Democratic | Leo Pfeffer (incumbent) | 2,306,163 | 0.44% | |

| Democratic | John W. Alsup (incumbent) | 2,306,002 | 0.44% | |

| Democratic | Michael H. McDermott (incumbent) | 2,305,217 | 0.44% | |

| Democratic | Frank C. Wolf (incumbent) | 2,304,540 | 0.44% | |

| Democratic | William J. Frey | 2,303,934 | 0.44% | |

| Democratic | Dan E. Costello (incumbent) | 2,303,723 | 0.44% | |

| Democratic | Daniel O'Neill | 2,303,161 | 0.44% | |

| Democratic | Howard R. Slater | 2,301,528 | 0.44% | |

| Democratic | Charles F. Armstrong (incumbent) | 2,301,421 | 0.44% | |

| Democratic | Michael E. Hannigan (incumbent) | 2,299,077 | 0.44% | |

| Democratic | H. B. Tanner | 2,298,128 | 0.44% | |

| Democratic | Thomas J. Hanahan, Jr. | 2,297,898 | 0.44% | |

| Democratic | Francis J. Loughran (incumbent) | 2,297,846 | 0.44% | |

| Democratic | Frank X. Downey (incumbent) | 2,296,178 | 0.44% | |

| Democratic | Joseph Fennessey | 2,295,190 | 0.44% | |

| Democratic | Dan Teefey (incumbent) | 2,293,692 | 0.44% | |

| Democratic | Joseph Tumpach | 2,293,423 | 0.44% | |

| Democratic | Leo B. Obernuefemann | 2,292,278 | 0.44% | |

| Democratic | Matt Ropa (incumbent) | 2,291,587 | 0.44% | |

| Democratic | James Y. Carter (incumbent) | 2,291,419 | 0.44% | |

| Democratic | Henry M. Lenard (incumbent) | 2,291,033 | 0.44% | |

| Democratic | Oral (Jake) Jacobs | 2,290,242 | 0.44% | |

| Democratic | John J. Houlihan | 2,289,912 | 0.44% | |

| Democratic | Frank J. Smith (incumbent) | 2,287,950 | 0.44% | |

| Democratic | Omer Sanders | 2,287,943 | 0.44% | |

| Democratic | Kenneth W. Course (incumbent) | 2,285,860 | 0.43% | |

| Democratic | Sam Romano (incumbent) | 2,285,599 | 0.43% | |

| Democratic | LaSalle J. DeMichaels | 2,285,455 | 0.43% | |

| Democratic | Andrew A. Euzzino (incumbent) | 2,284,415 | 0.43% | |

| Democratic | William A. Giblin | 2,284,254 | 0.43% | |

| Democratic | John P. Downes (incumbent) | 2,283,416 | 0.43% | |

| Democratic | John G. Fary (incumbent) | 2,283,240 | 0.43% | |

| Democratic | Edward J. Shaw (incumbent) | 2,283,155 | 0.43% | |

| Democratic | Peter J. Whalen (incumbent) | 2,281,873 | 0.43% | |

| Democratic | Robert F. McPartlin (incumbent) | 2,281,797 | 0.43% | |

| Democratic | John M. Vitek (incumbent) | 2,281,726 | 0.43% | |

| Democratic | John F. Leon (incumbent) | 2,281,623 | 0.43% | |

| Democratic | Edward F. Sensor | 2,281,431 | 0.43% | |

| Democratic | Joseph F. Fanta | 2,281,018 | 0.43% | |

| Democratic | Bernard B. Wolfe | 2,280,958 | 0.43% | |

| Democratic | Nicholas Zagone (incumbent) | 2,280,192 | 0.43% | |

| Democratic | Edward W. Wolbank (incumbent) | 2,279,315 | 0.43% | |

| Democratic | Frank Lyman (incumbent) | 2,279,018 | 0.43% | |

| Democratic | Peter M. Callan (incumbent) | 2,278,241 | 0.43% | |

| Democratic | Calvin L. Smith | 2,278,068 | 0.43% | |

| Democratic | Frank J. Broucek | 2,276,080 | 0.43% | |

| Democratic | Benedict Garmisa | 2,275,684 | 0.43% | |

| Democratic | Nick Svalina (incumbent) | 2,275,432 | 0.43% | |

| Democratic | Otis G. Collins | 2,274,028 | 0.43% | |

| Democratic | Lawrence DiPrima (incumbent) | 2,262,258 | 0.43% | |

| Republican | Earl D. Eisenhower | 2,191,826 | 0.42% | |

| Republican | Charles W. Clabaugh (incumbent) | 2,186,592 | 0.42% | |

| Republican | John Clinton Youle | 2,184,069 | 0.42% | |

| Republican | William E. Pollack (incumbent) | 2,178,460 | 0.41% | |

| Republican | Noble W. Lee (incumbent) | 2,177,503 | 0.41% | |

| Republican | Paul J. Randolph | 2,176,388 | 0.41% | |

| Republican | Mrs. Robert (Marjorie) Pebworth | 2,175,501 | 0.41% | |

| Republican | Frances L. Dawson (incumbent) | 2,173,989 | 0.41% | |

| Republican | Lawrence X. Pusateri | 2,172,480 | 0.41% | |

| Republican | Carl W. Soderstrom (incumbent) | 2,172,032 | 0.41% | |

| Republican | George F. Sisler | 2,171,458 | 0.41% | |

| Republican | John C. Parkhurst (incumbent) | 2,169,751 | 0.41% | |

| Republican | John W. Carroll (incumbent) | 2,169,659 | 0.41% | |

| Republican | Terrel E. Clarke (incumbent) | 2,167,451 | 0.41% | |

| Republican | Albert W. Hachmeister (incumbent) | 2,166,786 | 0.41% | |

| Republican | William D. Walsh (incumbent) | 2,166,243 | 0.41% | |

| Republican | J. David Jones | 2,165,919 | 0.41% | |

| Republican | Mrs. Brooks McCormick | 2,165,415 | 0.41% | |

| Republican | William L. Blaser | 2,163,785 | 0.41% | |

| Republican | George Thiem | 2,162,963 | 0.41% | |

| Republican | Maj. Gen. Robert M. Woodward | 2,161,782 | 0.41% | |

| Republican | Thomas F. Railsback (incumbent) | 2,161,428 | 0.41% | |

| Republican | Harris Rowe (incumbent) | 2,159,212 | 0.41% | |

| Republican | Richard A. Walsh (incumbent) | 2,158,621 | 0.41% | |

| Republican | Arthur E. Simmons (incumbent) | 2,157,072 | 0.41% | |

| Republican | George M. Burditt | 2,156,996 | 0.41% | |

| Republican | Clarence E. Neff (incumbent) | 2,156,668 | 0.41% | |

| Republican | Lewis V. Morgan, Jr. (incumbent) | 2,155,932 | 0.41% | |

| Republican | Alan R. Johnston (incumbent) | 2,155,834 | 0.41% | |

| Republican | John H. Conolly (incumbent) | 2,155,828 | 0.41% | |

| Republican | Ronald A. Hurst | 2,155,622 | 0.41% | |

| Republican | John W. Lewis, Jr. (incumbent) | 2,154,348 | 0.41% | |

| Republican | Leslie N. Jones | 2,153,681 | 0.41% | |

| Republican | G. William Horsley (incumbent) | 2,152,602 | 0.41% | |

| Republican | John Henry Kleine | 2,152,221 | 0.41% | |

| Republican | Herbert F. Geisler | 2,151,603 | 0.41% | |

| Republican | James H. Oughton, Jr. | 2,150,431 | 0.41% | |

| Republican | Paul P. Boswell, M.D. | 2,149,578 | 0.41% | |

| Republican | Edward H. Jenison | 2,149,326 | 0.41% | |

| Republican | Mary K. Meany | 2,147,427 | 0.41% | |

| Republican | Eugene F. Schlickman | 2,145,913 | 0.41% | |

| Republican | W. Robert Blair | 2,145,703 | 0.41% | |

| Republican | Jack T. Knuepfer | 2,143,965 | 0.41% | |

| Republican | Ralph T. Smith (incumbent) | 2,143,304 | 0.41% | |

| Republican | Wayne Fitzgerrell (incumbent) | 2,142,955 | 0.41% | |

| Republican | Robert R. Canfield | 2,142,725 | 0.41% | |

| Republican | Carl L. Klein | 2,142,638 | 0.41% | |

| Republican | Francis J. Berry | 2,142,274 | 0.41% | |

| Republican | Stanley A. Papierz | 2,141,662 | 0.41% | |

| Republican | Ben S. Rhodes (incumbent) | 2,141,539 | 0.41% | |

| Republican | Don A. Moore (incumbent) | 2,140,695 | 0.41% | |

| Republican | Bernard McDevitt (incumbent) | 2,139,731 | 0.41% | |

| Republican | C. L. McCormick (incumbent) | 2,138,193 | 0.41% | |

| Republican | Jack Bowers | 2,137,573 | 0.41% | |

| Republican | Dr Edwin E. Dale (incumbent) | 2,137,486 | 0.41% | |

| Republican | Dean McCully (incumbent) | 2,136,128 | 0.41% | |

| Republican | Ed Lehman (incumbent) | 2,134,749 | 0.41% | |

| Republican | Michael A. Ruddy (incumbent) | 2,134,681 | 0.41% | |

| Republican | William J. "Bill" Cunningham | 2,134,243 | 0.41% | |

| Republican | W. K. (Kenny) Davidson (incumbent) | 2,132,504 | 0.41% | |

| Republican | Louis Janczak (incumbent) | 2,132,011 | 0.41% | |

| Republican | W. J. McDonald | 2,130,597 | 0.41% | |

| Republican | Joseph R. Hale (incumbent) | 2,128,570 | 0.40% | |

| Republican | Fred Branson (incumbent) | 2,127,908 | 0.40% | |

| Republican | Nick Keller | 2,126,958 | 0.40% | |

| Republican | Charles M. (Chuck) Campbell (incumbent) | 2,126,209 | 0.40% | |

| Republican | Edward McBroom (incumbent) | 2,126,189 | 0.40% | |

| Republican | George S. Brydia (incumbent) | 2,126,047 | 0.40% | |

| Republican | Harland D. Warren (incumbent) | 2,125,539 | 0.40% | |

| Republican | Robert J. Lehnhausen | 2,124,841 | 0.40% | |

| Republican | Charles K. Willett (incumbent) | 2,124,588 | 0.40% | |

| Republican | A. B. McConnell (incumbent) | 2,124,433 | 0.40% | |

| Republican | William F. Martin | 2,123,689 | 0.40% | |

| Republican | John E. Velde, Jr. | 2,122,408 | 0.40% | |

| Republican | Meade Baltz (incumbent) | 2,121,885 | 0.40% | |

| Republican | H. B. Ihnen (incumbent) | 2,120,757 | 0.40% | |

| Republican | John W. Johnson | 2,119,621 | 0.40% | |

| Republican | John J. Donovan (incumbent) | 2,119,546 | 0.40% | |

| Republican | Frank A. Marek (incumbent) | 2,119,175 | 0.40% | |

| Republican | Garrel Burgoon (incumbent) | 2,118,800 | 0.40% | |

| Republican | Edward M. Finfgeld (incumbent) | 2,118,682 | 0.40% | |

| Republican | Edward Schneider (incumbent) | 2,118,514 | 0.40% | |

| Republican | Raymond E. (Ray) Anderson (incumbent) | 2,118,462 | 0.40% | |

| Republican | Merle K. Anderson (incumbent) | 2,118,328 | 0.40% | |

| Republican | Orval W. Hittmeier (incumbent) | 2,118,246 | 0.40% | |

| Republican | Paul F. Jones (incumbent) | 2,117,605 | 0.40% | |

| Republican | Claude A. Walker (incumbent) | 2,117,257 | 0.40% | |

| Republican | J. Horace Gardner (incumbent) | 2,116,919 | 0.40% | |

| Republican | Hubert A. Dailey | 2,116,519 | 0.40% | |

| Republican | Bradley L. Manning | 2,116,339 | 0.40% | |

| Republican | Albert E. Bennett | 2,116,319 | 0.40% | |

| Republican | Charles O. Miller (incumbent) | 2,116,139 | 0.40% | |

| Republican | Kenneth W. Miller (incumbent) | 2,116,012 | 0.40% | |

| Republican | Marshall R. Schroeder | 2,115,493 | 0.40% | |

| Republican | George P. Johns (incumbent) | 2,115,224 | 0.40% | |

| Republican | Edwin A. McGowan (incumbent) | 2,115,107 | 0.40% | |

| Republican | Elwood Graham (incumbent) | 2,114,521 | 0.40% | |

| Republican | Arthur J. Reis | 2,114,337 | 0.40% | |

| Republican | Ben C. Blades (incumbent) | 2,114,263 | 0.40% | |

| Republican | Carl T. Hunsicker (incumbent) | 2,114,146 | 0.40% | |

| Republican | Allan L. "Al" Schoeberlein (incumbent) | 2,113,809 | 0.40% | |

| Republican | John F. Wall (incumbent) | 2,113,500 | 0.40% | |

| Republican | Oscar Hansen (incumbent) | 2,113,266 | 0.40% | |

| Republican | Paul K. Zeman | 2,113,065 | 0.40% | |

| Republican | Jack E. Walker (incumbent) | 2,112,532 | 0.40% | |

| Republican | Edward A. Bundy | 2,111,052 | 0.40% | |

| Republican | Sydney L. "Syd" Perkins | 2,109,299 | 0.40% | |

| Republican | Eugene T. Devitt | 2,108,237 | 0.40% | |

| Republican | Jack D. Songer | 2,107,794 | 0.40% | |

| Republican | David W. Johnson | 2,105,944 | 0.40% | |

| Republican | Richard L. LoDestro (incumbent) | 2,104,909 | 0.40% | |

| Republican | James D. Heiple | 2,104,813 | 0.40% | |

| Republican | Romie J. Palmer | 2,103,232 | 0.40% | |

| Republican | J. Theodore Meyer | 2,103,129 | 0.40% | |

| Republican | Raymond J. Kahoun (incumbent) | 2,098,387 | 0.40% | |

| Republican | Norbert L. Lundberg | 2,098,300 | 0.40% | |

| Republican | Alfred B. Two | 2,098,286 | 0.40% | |

| Republican | Hellmut W. Stolle (incumbent) | 2,094,314 | 0.40% | |

| Total votes | 525,723,540 | 100% | ||

Aftermath

The results provided a significant shake-up of the balance of power in the state. While Republicans had maintained control of the Illinois Senate, Democrats held the governorship and won a two-thirds supermajority in the State House. Democrats elected John P. Touhy as the speaker of the House.[36]

Governmental reform

The election of many "blue ribbon" candidates in both parties led to a focus on governmental reform, especially regarding improving how the legislature operated.[2]: 290 The legislature formed the Illinois Commission on the Organization of the General Assembly, chaired by state representative Harold A. Katz.[37]: iv In 1967, the commission published Improving the State Legislature, which detailed 87 improvements it found that could be made to state government.[37]: 87 Building on this, the 75th General Assembly (elected in 1966) proposed a constitutional convention, which was approved by voters in 1968, creating the Sixth Illinois Constitutional Convention. The convention was successful in creating a new constitution, which was approved by voters in 1970.[2]: 290

Redistricting

One of the first matters the newly elected legislature had to consider was redistricting. New maps for the State House had to be passed to avoid another at-large election, while new maps for the State Senate had to be passed to comply with the Supreme Court's ruling in Reynolds v. Sims, which required that state legislature districts be roughly equal in population. There was again difficulty in passing maps, with downstate and Chicago legislators not wanting to give up representation in favor of the suburbs, which had grown their relative share of the population. In the end, a five-judge panel decided redistricting for the State Senate, while a legislative committee appointed by the governor was responsible for redistricting the House. The resulting maps were relatively fair to both parties, although they caused a significant shift of power from downstate to the Chicago area.[38]: 17

Illinois's constitution was rewritten in 1970. The new constitution modified the procedures for redistricting, adding a tie-breaker to the redistricting commission that would be established if the legislature failed to redistrict.[38]: 18 The tie-breaker would only be added if the commission deadlocked, and would be randomly chosen by the Secretary of State, with one candidate nominated by each party.[2]: 308

The legislative process was not successful for redistricting in 1971, 1981, 1991, or 2001, necessitating a commission be formed in each case. In 1971, the commission was successful without a tie-breaker.[2]: 308 A tie-breaker was needed in 1981, with a Democrat being chosen by Secretary of State Jim Edgar; the resulting map was biased in favor of the Democratic Party.[2]: 310 In 1991, the legislature, controlled by Democrats, passed a map that was vetoed by now-governor Edgar. With the commission initially unsuccessful, Secretary of State George Ryan chose a Republican for the tie-breaker. However, the Supreme Court, controlled by Democrats, rejected the commission's initial plan, threatening an at-large election if the commission could not create a valid plan.[2]: 310 Ryan described this as a potential constitutional crisis.[18] The commission eventually enacted a map which survived court challenges after a Democrat on the court voted with the court's Republicans to uphold the map.[2]: 310 In 2001, the commission needed a tie-breaker, with Secretary of State Jesse White selecting a Democrat; the commission passed its maps on a party-line basis.[2]: 310

The failure of the legislature to redistrict in every cycle between 1965 and 2001, as well as the commission failing in most of those years without a tie-breaker, has received significant criticism. Politicians have been described as choosing to play "redistricting roulette" in attempts to get a favorable map, instead of compromising to draw a fair one.[2]: 311 As of 2001, Illinois was the only state to use a randomly selected tie-breaker for its redistricting commission.[2]: 311

This was the only time in which a state legislative election was held at-large in the United States.[23] However, at-large elections have been held for all of a state's congressional seats due to similar failures to redistrict.[39]

Members elected

The 1964 election helped launch the political careers of certain Democrats, including Adlai E. Stevenson III, who later represented Illinois in the U.S. Senate, and Harold Washington, who eventually became mayor of Chicago.[18] The last member elected in 1964 to leave the House was Edolo J. Giorgi, a Democrat from Rockford, who served until his death in 1993.[18][40]

In 2000, Pat Quinn, a state politician and future governor, proposed that some members of the Illinois legislature should be elected at-large, arguing that the 1964 election had produced many good legislators.[2]: 312

Notes

- 1 2 Popular vote figures represent the total amounts of Democratic and Republican votes. Since every voter could vote for 177 candidates, this sums to a grand total much larger than the population of Illinois.

- ↑ Districts were used for both the House of Representatives and the Senate. Each district elected one member to the Senate and three to the House of Representatives with a version of cumulative voting, where each voter had three votes, and had the option to vote multiple times for a single candidate. This system was intended to ensure a bipartisan delegation from each district.[2]: 291

- 1 2 Includes the Chicago Daily News and the Chicago Sun-Times.[23]

- 1 2 Includes The Southern Illinoisan, the Champaign–Urbana Courier, the Decatur Herald and Review, and the East St. Louis Journal.[23]

- ↑ Lewis V. Morgan, Jack T. Knuepfer, Jack Bowers, Arthur J. Reis, and Edward A. Bundy[30]

- ↑ The exact membership counts differ slightly between McDowell 2007 and the 1965–1966 Illinois Blue Book, which it cites as its source.[34]: 195–311

References

- 1 2 "Official Vote of the State of Illinois". Illinois State Board of Elections. 1962. Retrieved September 16, 2023.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 29 30 31 32 33 34 35 36 37 38 39 40 41 42 43 44 45 46 47 48 49 McDowell, James L. (2007). "The Orange-Ballot Election: The 1964 Illinois At-Large Vote—and After". Journal of Illinois History. 10: 289–314.

- ↑ Carpentier, Charles F. (ed.). Illinois Blue Book (1961-1962 ed.).

- 1 2 3 Wehrwein, Austin (October 29, 1964). "Ballot in Illinois Big as Bath Towel". The New York Times. Retrieved March 8, 2021.

- 1 2 Chamberlain, William H. (ed.). Illinois Blue Book (1963-1964 ed.).

- 1 2 "Kerner Names Commission for House Remap". The Daily Register. August 15, 1963. Retrieved October 26, 2023.

- 1 2 3 4 "Redistricting Deadline Tonight; Still Hoping". The Telegraph. Associated Press. December 14, 1963. Retrieved October 26, 2023.

- ↑ Wood, Percy (November 4, 1963). "Here's What Remap Fight is All About". Chicago Tribune. pp. 1–2. Retrieved October 26, 2023.

- ↑ "Redistricting Veto Studied by High Court". Belleville News-Democrat. Associated Press. November 12, 1963. Retrieved October 26, 2023.

- 1 2 3 "Illinois to Elect House At-large". The New York Times. January 5, 1964. Retrieved April 12, 2023.

- ↑ Bakke, Bruce B. (November 22, 1963). "GOP Boycotts Remap Sessions; Another Lawsuit Filed". Edwardsville Intelligencer. United Press International. Retrieved October 26, 2023.

- ↑ "Senate Aspirant Asks At-Large Court Ruling". The Pantagraph. United Press International. December 22, 1963. Retrieved October 26, 2023.

- ↑ People Ex Rel. Giannis v. Carpentier, 30 Ill. 2d, 24 (Supreme Court of Illinois January 4, 1964).

- 1 2 3 "Illinois Sets Up At-large Voting". The New York Times. January 30, 1964. Retrieved April 12, 2023.

- ↑ "Court Rejects Challenge to At-Large Vote". Herald & Review. Springfield. Associated Press. April 22, 1964. Retrieved October 28, 2023.

- ↑ Howard, Robert (June 4, 1964). "Legal Blocks Seen to Third Slate in State". Chicago Tribune. p. 23. Retrieved January 11, 2024.

- 1 2 3 "Newspaper Supplement Explains At-Large House Vote". The Southern Illinoisan. October 25, 1964. Retrieved April 12, 2023.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 Pearson, Rick; Hardy, Thomas (December 17, 1991). "Ruling Rekindles Visions of '64 'Bedsheet' Ballot". Chicago Tribune. Retrieved 2021-03-08.

- ↑ "This 'Third Slate' Different". The Pantagraph. August 6, 1964. Retrieved September 17, 2023.

- ↑ "Third Slate Party Now Distributing Petitions". The Daily Register. Peoria. July 31, 1964. Retrieved September 17, 2023.

- ↑ "Third Party is Ruled Out". Daily Chronicle. August 21, 1964. Retrieved September 17, 2023.

- ↑ "Questions and Answers on Illinois At-Large Election". The Daily Register. September 24, 1964.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 McDowell, James L. (June 1965). "The Role of Newspapers in Illinois' At-Large Election". Journalism Quarterly. 42 (2): 281–284. doi:10.1177/107769906504200217. S2CID 144140012. Retrieved November 6, 2023.

- ↑ "Suburb Candidates Merit Our Support". Daily Herald. October 8, 1964.

- ↑ "Results Are Delayed". Chicago Tribune. November 4, 1964. Retrieved September 17, 2023.

- ↑ Howard, Robert (November 5, 1964). "Illinois House Vote Count Delayed". Chicago Tribune. Retrieved September 17, 2023.

- ↑ "Results to be Kept Secret Till Canvass". Chicago Tribune. November 9, 1964. Retrieved September 17, 2023.

- ↑ "Downstaters Head G.O.P. Ballot; Chicagoans Trail". Chicago Tribune. November 26, 1964. Retrieved September 17, 2023.

- ↑ "35 in G.O.P. Lose State House Seats". Chicago Tribune. December 4, 1964. Retrieved September 17, 2023.

- ↑ "Injunction Lifted, Recount Still Asked". Daily Herald. December 10, 1964. Retrieved November 16, 2023.

- ↑ Weston, Jean (December 17, 1964). "Attorney General Enters Vote Hassle". Daily Herald. Wheaton. Retrieved September 17, 2023.

- ↑ "Won't Delay Legislature, Judge Vows". Chicago Tribune. December 25, 1964. Retrieved September 17, 2023.

- ↑ Weston, Jean (January 7, 1965). "Democrats Blast Locke's Order to Recount Ballots". Daily Herald. Retrieved September 17, 2023.

- 1 2 Powell, Paul (ed.). Illinois Blue Book (1965-1966 ed.).

- ↑ "Official Vote of the State of Illinois". Illinois State Board of Elections. 1964. Retrieved September 16, 2023.

- ↑ Simpson, Bob (January 7, 1965). "Touhy Elected Speaker of House". The Pantagraph. Retrieved September 17, 2023.

- 1 2 Improving the State Legislature: A Report of the Illinois Commission on the Organization of the General Assembly. Urbana: University of Illinois Press. 1967.

- 1 2 Green, Paul M. (1987). Legislative Redistricting in Illinois: An Historical Analysis (PDF) (Report). Illinois Commission on Intergovernmental Cooperation.

- ↑ Montgomery, David H. (February 23, 2021). "Minnesota races for Congress in 2022 could get wild". Minnesota Public Radio. St. Paul, Minnesota. Retrieved December 22, 2023.

- ↑ Pearson, Rick (October 25, 1993). "Rep Edolo J. Giorgi; Created State Lottery". Chicago Tribune. Retrieved October 9, 2023.

.png.webp)